Engagement on School Food Data and Research Priorities (2025): What We Heard

Original title: Engagement on School Food Data and Research Priorities (2025): What We Heard

On this page

Alternate formats

Engagement on School Food Data and Research Priorities (2025) - What we heard [PDF - 1.7 MB]

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

Executive summary

The Government of Canada is investing $1 billion over five years in the National School Food Program to work with provinces and territories and Indigenous partners to enhance and expand school food programs across Canada, guided by the National School Food Policy.

Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) and its partners are working to fill key gaps in data and knowledge related to school food programming in Canada. The goal is to build a strong, evidence-based program that helps improve health, learning, and access to nutritious food at school - ensuring every generation has the support they need to reach their full potential. To inform this work, ESDC conducted a national engagement in January and February 2025 with the following objectives:

- Identify gaps and priorities in school food data and research.

- Identify the best ways to share school food research findings.

- Guide future school food data and research activities in Canada.

Through an online questionnaire and written submissions, individuals and organizations with expertise in school food shared their perspectives. This report summarizes what we heard.

Respondents noted a general lack of school food data and research in Canada, which limits opportunities to make evidence-based decisions about program delivery. They expressed a strong interest in local or region-specific research that showcases the diversity of school food programming across the country.

We heard about key barriers to advancing school food data and research in Canada, including:

- Limited funding for data and research activities.

- Difficulty applying research findings into practice.

- Differences in the way that school food programs are monitored and evaluated across jurisdictions.

Respondents indicated that, among various school food topics, the impacts of school food programming on students are most well-understood from existing data and research, while also being the most important to prioritize in future data and research activities. Many mentioned the need to capture a wide range of school food program outcomes and examine how these outcomes are connected (for example, how a program’s impacts on students can have secondary effects for their households and communities). Commonly suggested topics for future data and research activities included:

- Examining programs’ financial sustainability and cost-effectiveness.

- Tracking long-term impacts of participation over time.

- Measuring a range of outcomes at multiple levels, such as:

- Student outcomes (especially physical and mental health and academic performance).

- Household outcomes (especially household food insecurity and spending).

- Community outcomes (especially local food system and community economic development).

- Understanding how school food programs influence, and are influenced by, school food environments and food-related policies (for example, guidelines on nutrition or types of foods that can be served).

Respondents also stressed that research findings should be shared in ways that are practical, relevant and audience specific. For example:

- Video webinars were preferred by non-profit and community advocacy organizations’ staff and volunteers.

- Infographics were generally well-received across respondent types.

The perspectives shared through this engagement provide a snapshot of the state of school food data and research evidence during the early stages of the National School Food Program’s implementation. Findings will guide future data and research activities, helping to build a more robust and actionable evidence base for Canadian school food programs in the years to come.

Overview

About the engagement

Public online questionnaire

ESDC invited those who previously engaged with the department on the development of the National School Food Policy, summarized in a separate What We Heard Report, and others with relevant school food knowledge and expertise to participate in an online questionnaire to help identify gaps and priorities in school food data and research in Canada.

The online questionnaire was open from January 30 to February 28, 2025. 281 responses were received through the online questionnaire platform.

The questionnaire included a combination of multiple selection, ranking, and open text box questions about four key areas related to school food data and research in Canada:

- Existing data and research evidence.

- Data and research challenges.

- Data and research priorities moving forward.

- Sharing of data and research.

Written submissions

Four organizations provided a written response to the questionnaire via email. The perspectives shared in these written submissions are reflected throughout this report.

Respondent characteristics

A total of 285 responses were received.

- 99% of respondents completed the questionnaire as individuals. The remaining 1% of respondents completed the questionnaire on behalf of an organization (all via emailed submissions), and did not provide demographic information (for example, regarding gender and location).

- 87% of respondents completed the questionnaire in English, and 13% completed the questionnaire in French.

- 79% identified as women, 13% identified as men, 1% identified as non-binary and 7% chose not to respond.

- There was representation from all provinces and territories. Most respondents were from Ontario (48%), Quebec (13%) and British Columbia (11%).

- There was a wide range of roles relevant to school food, including:

| Role | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Non-profit or community / advocacy organization staff / volunteer | 103 | 37% |

| Other (for example, other school staff, public health staff, health professionals) | 49 | 17% |

| Researcher | 47 | 17% |

| School board staff / volunteer group | 36 | 13% |

| Indigenous government / Indigenous community or advocacy organization | 30 | 11% |

| Corporation staff | 9 | 3% |

| Prefer not to answer | 7 | 2% |

| Total | 281 | 100% |

- Note: Written responses did not include demographic information and are excluded from Table 1.

Of respondents in the non-profit or community / advocacy roles category in Table 1 (collectively representing 37% of all respondents):

- 32% had roles in community / advocacy organizations, 21% in service delivery organizations, 17% in health organizations, 14% in food and agriculture organizations, 7% in food education organizations; and the remaining 9% responded “other.”

Of respondents in the Indigenous government, community / advocacy roles category in Table 1 (collectively representing 11% of all respondents):

- 30% identified as Indigenous non-profit or community / advocacy organizational staff or volunteers, 20% identified as an Indigenous government member, 13% identified as part of an advocacy or representative body; and the remaining 37% responded “other” or “prefer not to answer.”

What we heard – Key takeaways

This report reflects respondents’ views on school food data and research, rather than program delivery more broadly. The findings are not intended to represent all Canadians, ESDC partners or stakeholders, and not all comments are reflected. Throughout the report, we use the term “respondent” to credit views expressed.

Overall, respondents highlighted:

- Several gaps in available data and research in Canada.

- Barriers to addressing these gaps

- Priority areas for future study.

- The importance of sharing findings in ways that lead to action.

School food data and research evidence in Canada

Finding 1: There is a general lack of school food data and research in Canada.

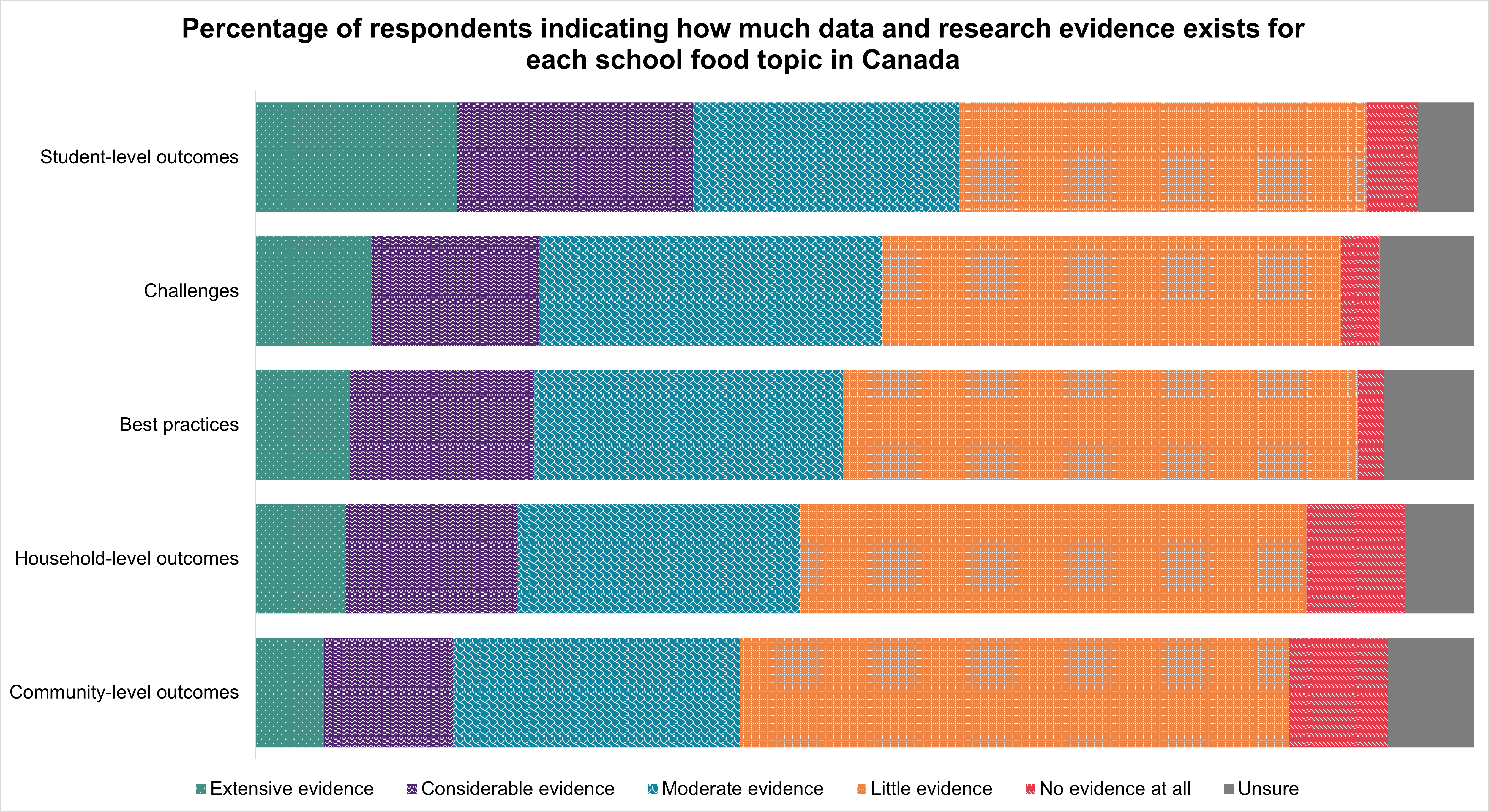

Respondents were asked to indicate how much data and research evidence currently exists for five key school food data and research topics in Canada. These topics included:

- Student-level outcomes (for example, academic achievement and physical or mental health).

- Household-level outcomes (for example, household food insecurity, reduced household food costs).

- Community-level outcomes (for example, community food security, community involvement and empowerment).

- Best practices for school food program operations and delivery (for example, practices that reduce barriers to program participation or create efficiencies in program delivery).

- Challenges for school food program operations and delivery (for example, those related to financial and personnel limitations).

Many respondents (between 37-53% of respondents, depending on the topic) felt that there was “little evidence” or “no evidence at all” on these topics within the existing Canadian evidence base (see Annex A for full questionnaire findings).

Some respondents noted that there was considerable evidence from other countries showing the benefits of school food programs but felt more Canadian research is needed to support evidence-based programming decisions.

Respondent view

“There are many studies in other countries that address these topics, but few within [Canada] addressing the Canadian context.”

Finding 2: School food programs’ impacts on students are well-documented in current research, yet further investigation of these impacts and other priority areas is needed.

Of all school food topics, respondents felt that programs’ impacts on students were the most well-understood. More than one third of respondents (36%) reported that there was “considerable” or “extensive” evidence for student-level outcomes of school food programs.

Fewer respondents felt that there was “considerable” or “extensive” evidence related to school food best practices and challenges (23% each), and especially, household-level (21%) and community-level (16%) outcomes.

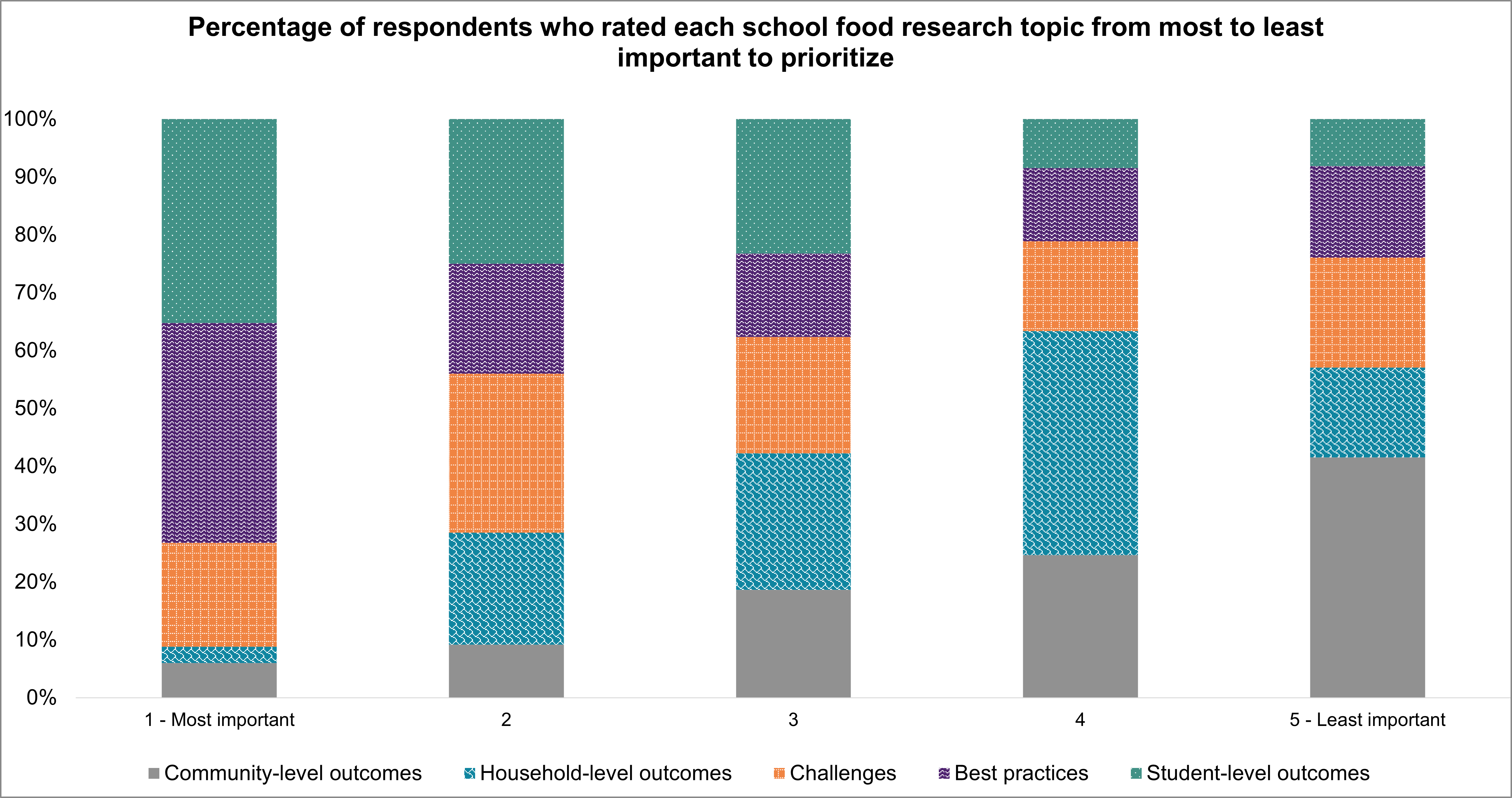

Respondents were also asked to rank these five school food topics from most to least important to prioritize in future data and research activities. 60% of respondents ranked student-level outcomes as either their first or second priority, even though many identified that this topic was addressed (at least to a “moderate” extent) within existing data and research. Taken together, these findings might suggest that existing data and research on school food programs’ student-level outcomes is outdated, limited in scope, or from countries other than Canada.

Many respondents identified best practices (57%) and challenges (45%) as their first or second priority topic out of the five topics.

Several respondents shared other reflections on school food data and research evidence in Canada. We heard that data and research are needed:

- To better understand the long-term impacts and benefits of school food programs.

- On community-level outcomes.

- On the impacts of school food programs within remote and Northern communities.

- To better incorporate Indigenous food sovereignty and diversity, equity and inclusion efforts into school food programming.

Respondent views

“The government should fund a longitudinal cohort study, which would consist of a research team ensuring the follow-up of a large group of people over a long period of time to understand the long-term impact of the programs on children (who are now adults).”

“We know from national and abroad research the positive impact of healthy nutrition on kids’ development and well-being, but we need more research on local realities. We should be conducting research at provincial and community levels.”

“Equity, diversity, and inclusion (EDI) in school food programs. This falls under challenges but I think we should also focus on opportunities and positive outcomes of incorporating Indigenous food sovereignty and EDI.”

Some respondents expressed that certain topics, specifically regarding programs’ benefits, are already well documented and do not require additional investigation. They felt that more concrete support for program delivery and implementation—such as through research on these topics and other actions—is needed.

Respondent views

“We fundamentally know the benefits of such a program. We need research on how best to execute the plan, with the challenges presented, in a way that aligns [with] our values of nutrition, health, diversity, cultural acceptance, & support for local economy.”

“Most of these issues have been researched enough, the benefits of school food programs are more than evident. We truly do not require another research or survey, we need implementation steps gearing towards universal programs free of stigmatization.”

Data and research challenges

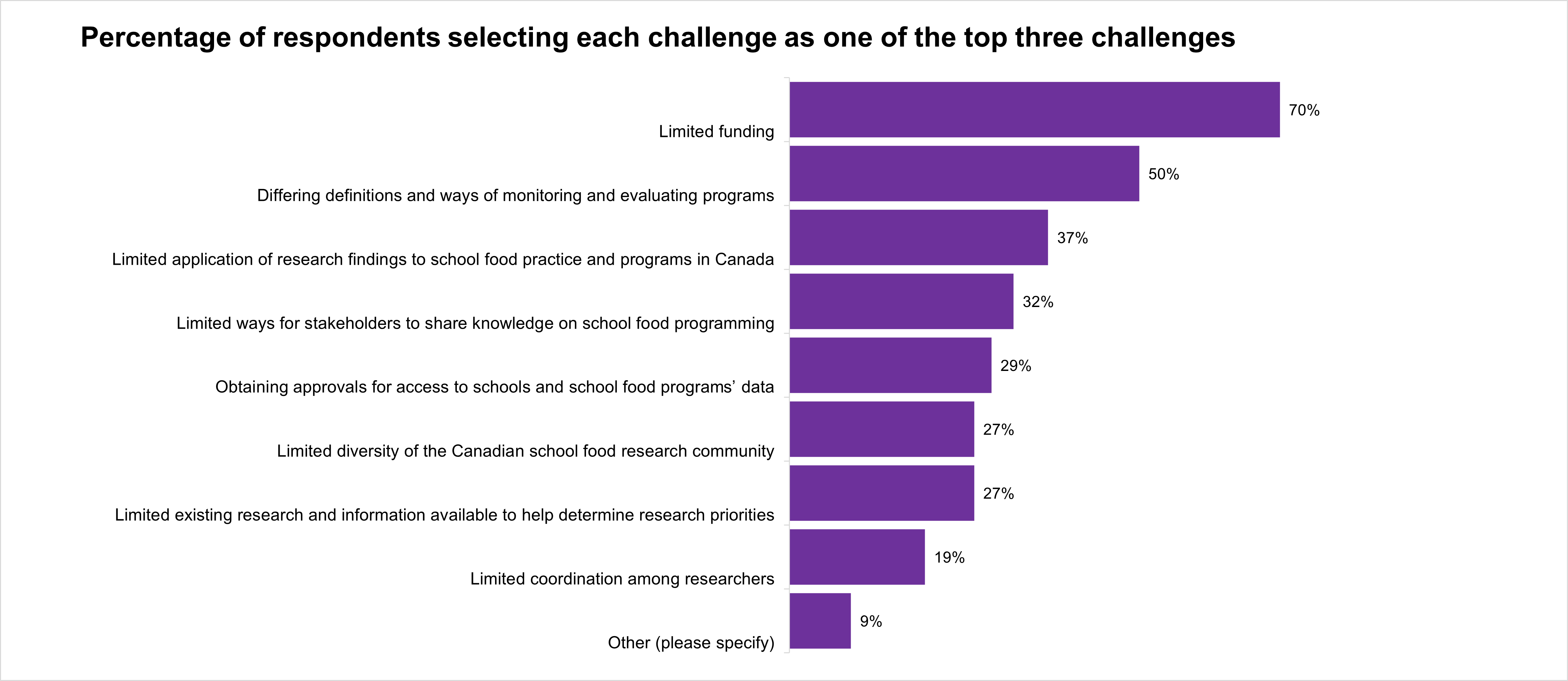

Finding 3: Various factors present challenges for school food data and research in Canada, particularly limited funding.

Respondents were asked to select the top three challenges, from a list of options, that should be addressed to have a positive impact on school food data and research in Canada. Respondents most often selected “limited funding” (70%), “different definitions and ways to monitor and evaluate programs” (50%) and “limited application of research findings into practice” (37%) as the top challenges.

Note: Since respondents selected their top three challenges, the percentages for each option do not total 100%.

Some respondents described other data and research challenges they felt should be addressed. We heard that:

- Programming, data and research methods are not consistent across regions. This poses challenges for summarizing evidence, as well as program monitoring and evaluation across Canada.

- There is limited collaboration between researchers and local school food programs. This decreases the potential to identify challenges and best practices.

- There is currently no centralized “hub” for school food data and research resources. This reduces awareness of and access to research findings.

Respondent views

“[There is] little co-operation between private and public stakeholders to inform best practices, address challenges, ensure sustainable compliant programs.”

“Currently Canada’s school food programs are so patchwork, it is hard to compare one program to another or one geographic area to another. How can we monitor and evaluate programs nationally if there are so many unique settings, providers, menus, etc.?”

“Each program is unique, making it difficult to gather data for comparison. There could be confounding variables that couldn’t be controlled for.”

Data and research priorities

Finding 4: Data and research priorities should include understanding how to deliver sustainable programs that benefit students, households, and communities.

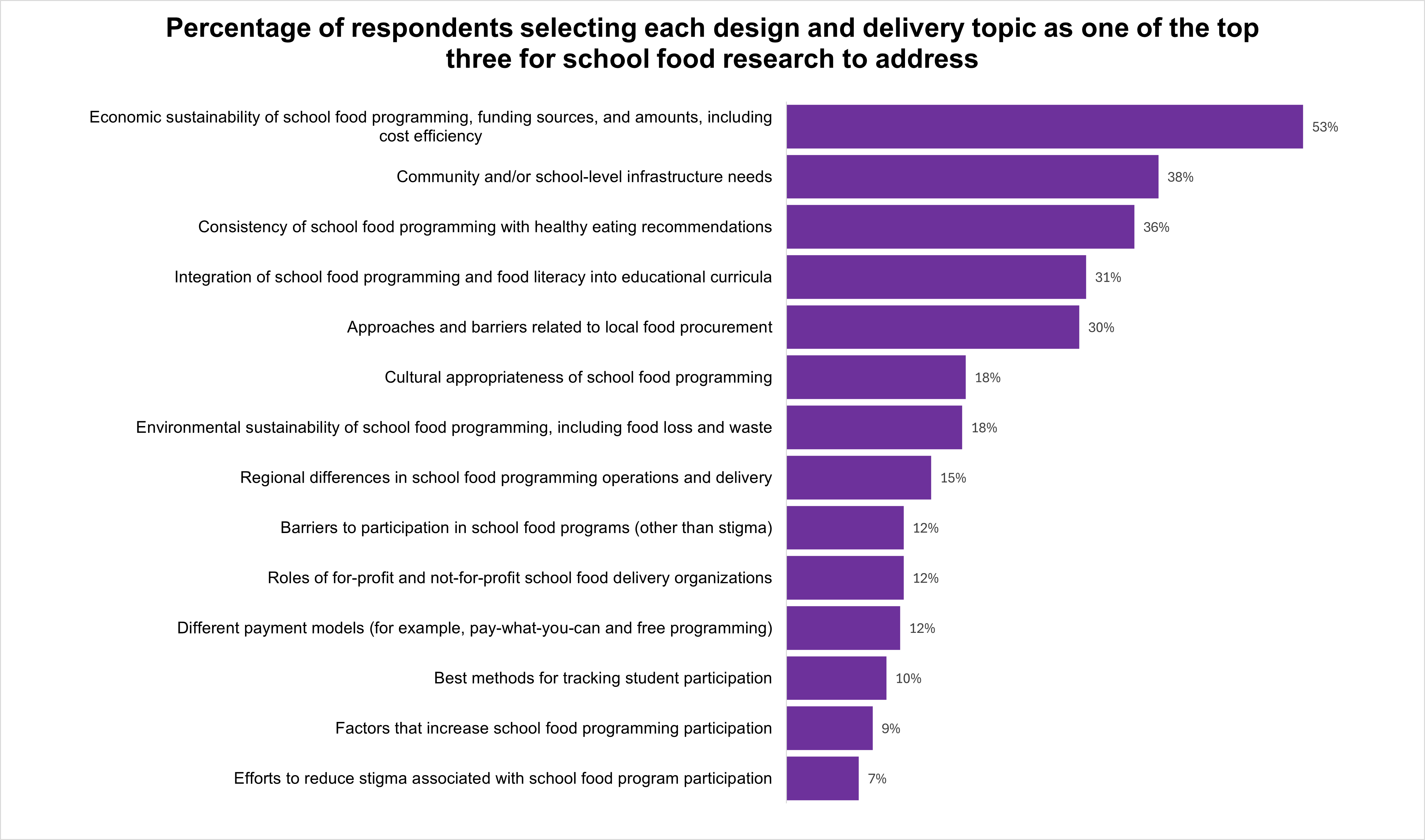

Priorities related to school food program design and delivery

Respondents were asked to select three topics, from a list of options related to school food program design and delivery, that they felt were most important to examine through future data and research activities. Examples of these topics include examination of payment models, infrastructure needs, and best ways to track participation.

A large share of respondents included “economic sustainability” (53%), “community and/or school-level infrastructure needs” (38%), and “consistency with healthy eating recommendations” (36%) among their top three priorities.

Some respondents described other priority topics related to school food program design and delivery. These included (more) research that examines:

- Program elements that optimize programs’ return-on-investment (that is, elements that maximize future benefits for children and youth, families, and communities relative to cost) without compromising program quality.

- How school food program menus and other features influence students’ participation in programs.

- School food personnels’ knowledge and training needs (such as training related to allergy safety and dietary requirements).

- Program delivery models and best practices that help to foster positive and inclusive school food environments.

- The connection between school food programs and nutrition policies (for example, exploring whether school food menus are compliant with nutrition guidelines).

- How school food policies and programs can be developed and strengthened, including to be region-specific and reduce stigma.

Respondent views

"As a publishing researcher on school food policy, we note a strong lack of research around the policy and political dynamics of school food in Canada.”

“We need data on long-term benefits in student academic and health outcomes and what program elements will lead to greater benefits and return-on-investment.”

“Delivery models of programs and how that relates to fostering a healthy school food environment. Do students have enough time to eat? Do they have the opportunity to socialize? Is there positive food and nutrition language and messaging in the school”

Priorities related to school food program impacts

Respondents were also asked to select three topics, from a list of options related to the impacts of school food programs, that they felt were most important for future data and research to examine. Examples of these topics include programs’ impacts on students’ eating habits and overall health and well-being.

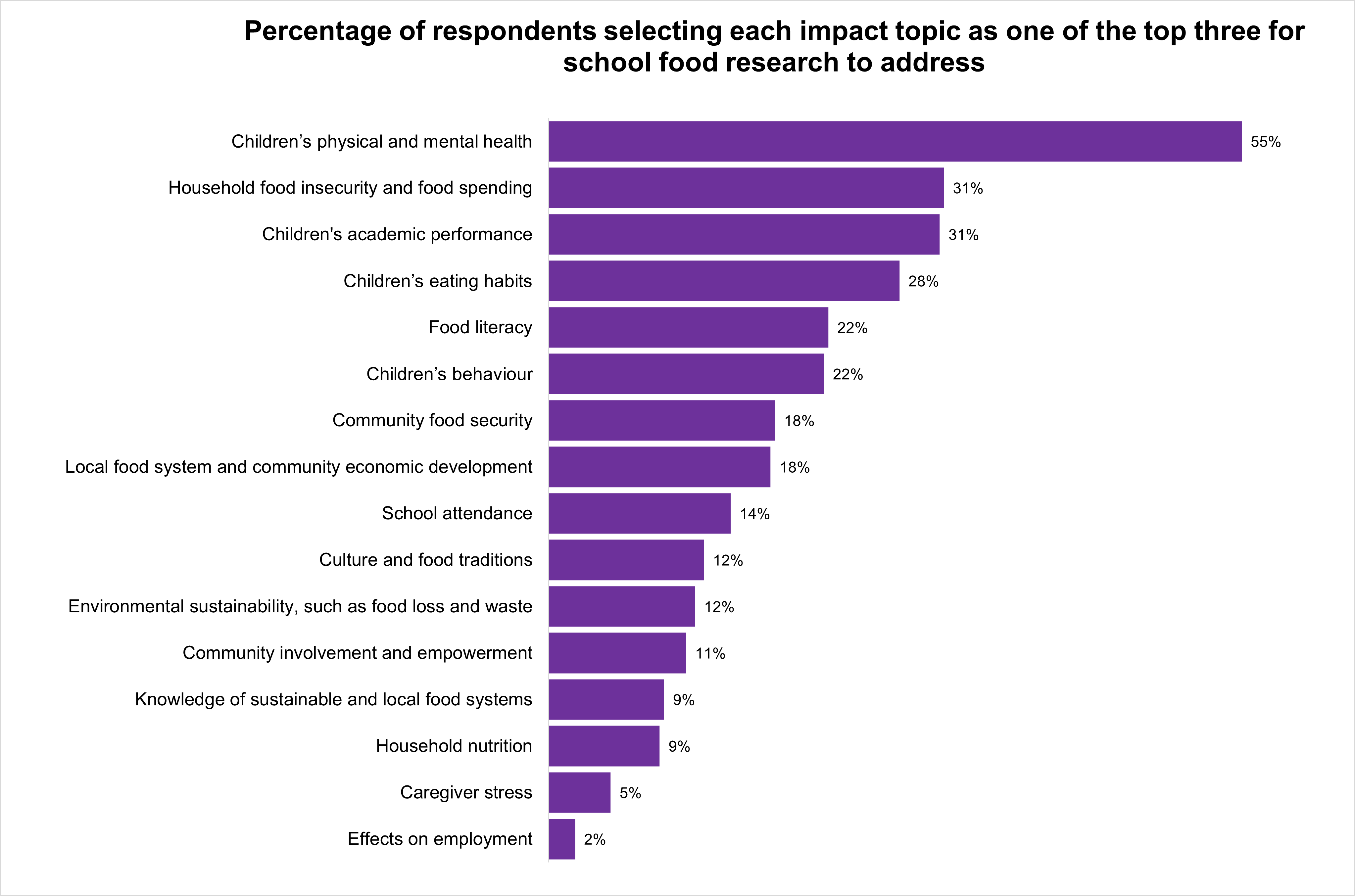

A large share of respondents selected “children’s physical and mental health” (55%), “household food insecurity and food spending” (31%), and “children’s academic performance” (31%) in their top three priorities.

Some respondents described other priority topics related to school food program impacts. These included wanting to better understand:

- The long-term impacts of school food programs on students, their households, and their communities, using longitudinal studies.

- The broader impacts of school food programs on school food environments, food systems and the economy.

- How the nutritional quality of school food meals and snacks affect students’ nutrition and health outcomes.

- The impacts of school food programs on other factors, including the development or improvement of supportive policies (for example, nutrition policies), children and youth’s food preferences and relationships with food, and students’ food and nutrition literacy.

Respondent views

“Long term cohort study would be very beneficial to understand and show outcomes of school food over time including how this intervention impact physical and mental health, education, lifetime earning, food literacy, etc.”

“Evaluating choice architecture on children’s lifelong dietary patterns and impact on lifelong health”

“Impact on school food environment, including policy (school nutrition policies, guidelines), physical (food program availability), and socio-cultural (nutrition education/knowledge) aspects of the school food environment.”

Sharing research

Finding 5: School food research can be more impactful when shared in ways that connect with the intended audiences.

Products and media for sharing research

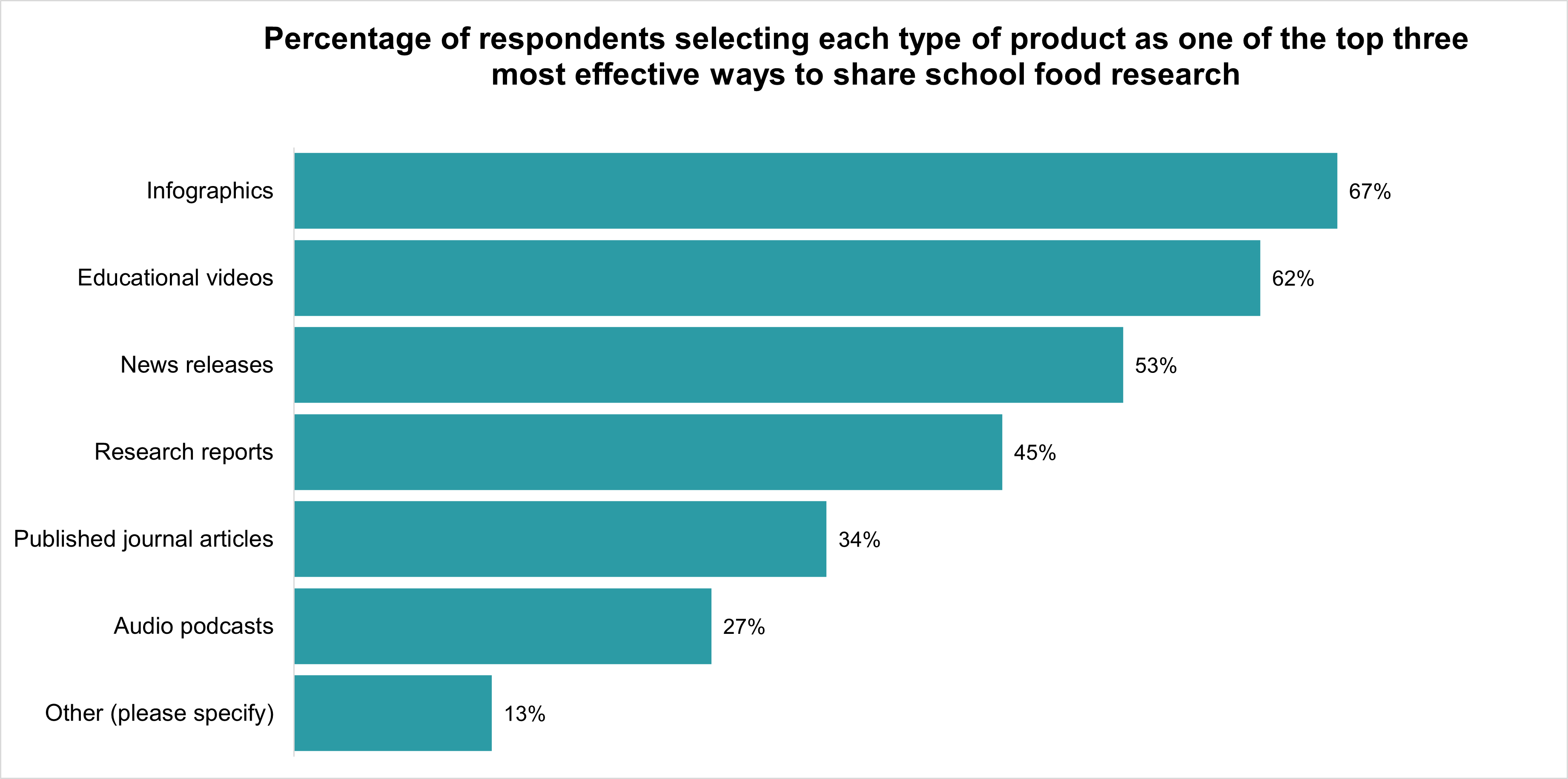

Respondents were asked to select three types of products or media, from a list of options, that they felt were most effective for sharing school food data and research.

Most respondents selected infographics (67%), educational videos (62%) and news releases (53%) among their top three, indicating a general preference for visual communication products.

Some respondents shared other perspectives on how to effectively share school food data and research in Canada. We heard that:

- Sharing research findings on social media is convenient and accessible to a wide audience.

- Plain language summaries and policy briefs can help make research available to knowledge users, such as school food practitioners, schools and communities.

- A centralized hub of school food resources (for example, a website) could make research easier for school food stakeholders to access.

Respondent views

“Social media channels, in-person presentations, for example, family gatherings, townhall events, guest speaker presentations.”

“Anything that presents data in accessible way, and helps encourage participation by showing the benefits and eliminate stigma against participation.”

“Published in areas where people can learn about this programming, many people still don’t know. It needs to be part of the curriculum, information going home to parents, in newspapers online, publications.”

Methods for sharing research

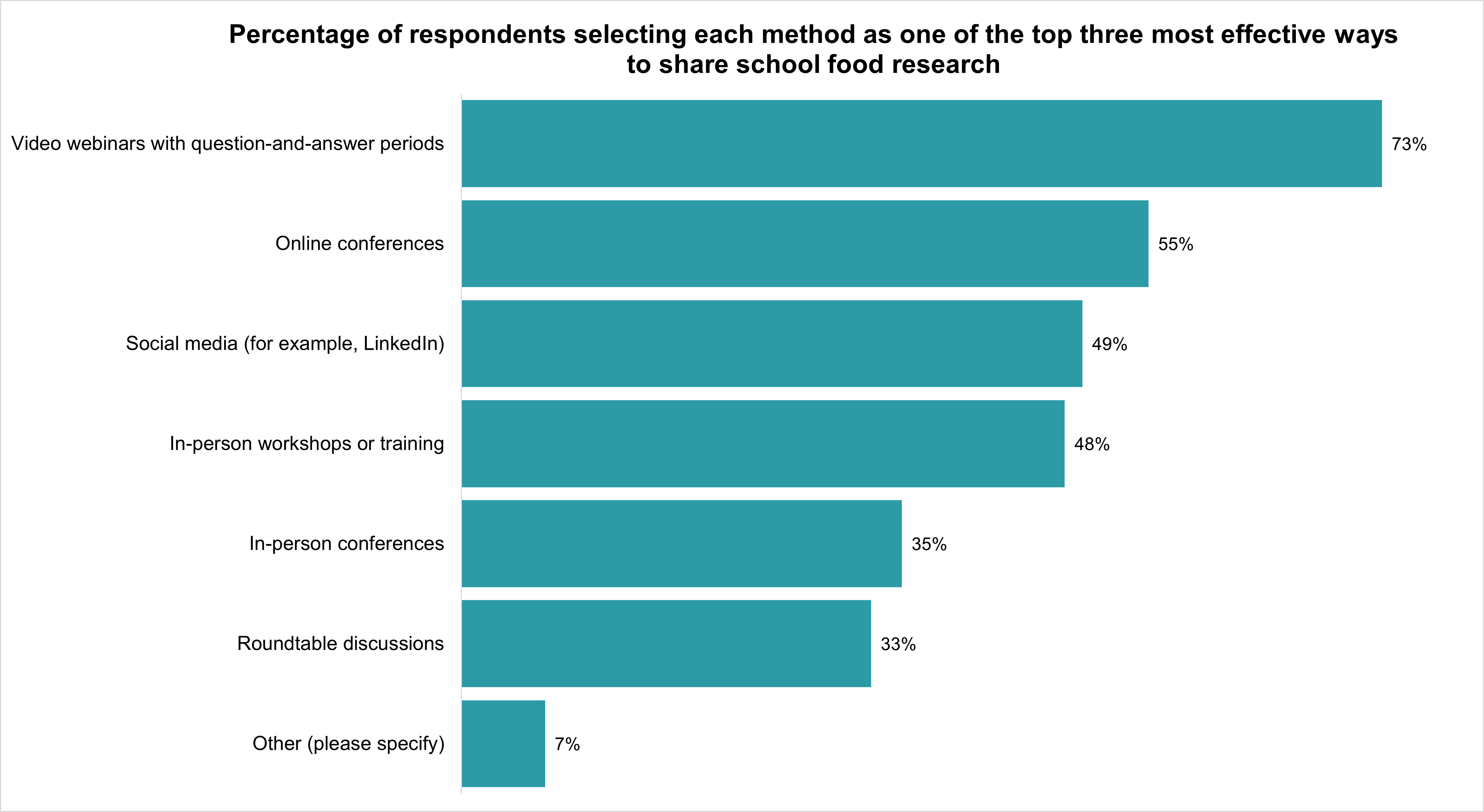

Respondents were asked to select three types of methods (that is, forums or approaches for sharing research products), from a list of options, they felt were most effective for sharing school food data and research.

Many respondents selected video webinars with a question-and-answer period (73%), online conferences (55%) and social media (49%) among their top three.

Some respondents shared other methods they felt were effective for sharing research about school food in Canada. We heard that:

- Events such as summits, tradeshows, workshops and webinars could provide opportunities to share school food knowledge.

- Sharing research with communities and schools directly (regardless of the specific method) can maximize its impact and application within local contexts.

We also heard that those who share school food data and research need to consider their audience and the products and methods are most meaningful to them. For example, respondents noted that some communities and audiences may prefer in-person opportunities over online products and events.

Respondent view

“For systems-level impact, research needs to reach a diverse audience of stakeholders, community members, policymakers and more. Amplification needs to occur. Working with journalists and relevant leaders provides robust platforms for dissemination”

What’s next

Through this engagement, we gained a better understanding of the school food data and research landscape and key data and research priorities, as identified by school food stakeholders and partners during the early implementation of the National School Food Program.

Respondents highlighted the importance of data and research in informing school food programming policies, practices and decision-making in Canada. We heard that respondents were especially interested in data and research examining long-term impacts of school food programs on students, including on their physical and mental health and academic outcomes. We also heard that visual products and online forums for sharing school food data and research are generally preferred.

Respondents highlighted several challenges related to school food data and research, such as limited funding, difficulties putting research findings into action, and research being difficult to find or understand.

ESDC has already taken steps to address the priority evidence gaps and challenges identified through this engagement, described below:

- Established bilateral agreements with provincial and territorial partners to engage in long-term collaboration and advance shared priorities through the implementation of the National School Food Program.

- Enabled population-level data collection on school food through a new module within Statistics Canada’s Canadian Income Survey.

- Launched a new research funding opportunity (a school food-focused funding stream within the Partnering for Impact – Catalyst Grant), in collaboration with the Canadian Institutes of Health Research).

ESDC will continue to collaborate with provincial, territorial and Indigenous partners to understand their perspectives and priorities regarding school food data and research, given their critical roles in school food program delivery across Canada.

Looking ahead, ESDC will also continue to monitor the state of school food evidence as it evolves, including to inform National School Food Program implementation and evaluation.

Acknowledgements

ESDC would like to thank everyone who completed the questionnaire or submitted a written response. Your feedback was thoughtful and wide-ranging, and we appreciate you sharing your views.

Annex A - Engagement questionnaire results summary

Questions about school food data and research evidence

Figure 1: “Please indicate, in your opinion, how much data and research evidence exists for the following school food topics in Canada” (text version – long description)

| School Food Topic | Extensive evidence | Considerable evidence | Moderate evidence | Little evidence | No evidence at all | Unsure |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student-level outcomes | 17% | 19% | 22% | 33% | 4% | 5% |

| Challenges | 10% | 14% | 28% | 38% | 3% | 8% |

| Best practices | 8% | 15% | 25% | 42% | 2% | 7% |

| Household-level outcomes | 7% | 14% | 23% | 42% | 8% | 6% |

| Community-level outcomes | 6% | 11% | 24% | 45% | 8% | 7% |

Figure 2: “Please rate the following list of school food research topic areas from most to least important to prioritize in research activities” (text version – long description)

| School Food Topic | 1 - Most important | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 - Least important |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Best practices | 38% | 19% | 14% | 13% | 16% |

| Student-level outcomes | 35% | 25% | 23% | 8% | 8% |

| Challenges | 18% | 27% | 20% | 15% | 19% |

| Community-level outcomes | 6% | 9% | 19% | 25% | 42% |

| Household-level outcomes | 3% | 19% | 24% | 39% | 15% |

Questions about data and research challenges

Figure 3: “Please select the three main challenges that should be addressed first to have a positive impact on school food data and research in Canada” (text version – long description)

| Challenge | % |

|---|---|

| Limited funding | 70% |

| Differing definitions and ways of monitoring and evaluating programs | 50% |

| Limited application of research findings to school food practice and programs in Canada | 37% |

| Limited ways for stakeholders to share knowledge on school food programming | 32% |

| Obtaining approvals for access to schools and school food programs’ data | 29% |

| Limited diversity of the Canadian school food research community | 27% |

| Limited existing research and information available to help determine research priorities | 27% |

| Limited coordination among researchers | 19% |

| Other (please specify) | 9% |

Questions about data and research priorities

Figure 4: “Please select the three main design and delivery topics that you feel are most important for school food research in Canada to address” (text version – long description)

| Process topic | % |

|---|---|

| Economic sustainability of school food programming, funding sources, and amounts, including cost efficiency | 53% |

| Community and/or school-level infrastructure needs | 38% |

| Consistency of school food programming with healthy eating recommendations | 36% |

| Integration of school food programming and food literacy into educational curricula | 31% |

| Approaches and barriers related to local food procurement | 30% |

| Cultural appropriateness of school food programming | 18% |

| Environmental sustainability of school food programming, including food loss and waste | 18% |

| Regional differences in school food programming operations and delivery | 15% |

| Barriers to participation in school food programs (other than stigma) | 12% |

| Roles of for-profit and not-for-profit school food delivery organizations | 12% |

| Different payment models (for example, pay-what-you-can and free programming) | 12% |

| Best methods for tracking student participation | 10% |

| Factors that increase school food programming participation | 9% |

| Efforts to reduce stigma associated with school food program participation | 7% |

Figure 5: “Please select the three main impact topics that you feel are most important for school food research in Canada to address” (text version – long description)

| Impact topic | % |

|---|---|

| Children’s physical and mental health | 55% |

| Household food insecurity and food spending | 31% |

| Children’s academic performance | 31% |

| Children’s eating habits | 28% |

| Food literacy | 22% |

| Children’s behaviour | 22% |

| Community food security | 18% |

| Local food system and community economic development | 18% |

| School attendance | 14% |

| Culture and food traditions | 12% |

| Environmental sustainability, such as food loss and waste | 12% |

| Community involvement and empowerment | 11% |

| Knowledge of sustainable and local food systems | 9% |

| Household nutrition | 9% |

| Caregiver stress | 5% |

| Effects on employment | 2% |

Questions about sharing research

Figure 6: “Please select what you feel are the three most effective types of products or media for sharing data and research about school food in Canada” (text version – long description)

| Products or media for research sharing | % |

|---|---|

| Infographics | 67% |

| Educational videos | 62% |

| News releases | 53% |

| Research reports | 45% |

| Published journal articles | 34% |

| Audio podcasts | 27% |

| Other (please specify) | 13% |

Figure 7: “Please select what you feel are the three most effective methods for sharing data and research about school food in Canada” (text version – long description)

| Methods for research sharing | % |

|---|---|

| Video webinars with question-and-answer periods | 73% |

| Online conferences | 55% |

| Social media (for example, LinkedIn) | 49% |

| In-person workshops or training | 48% |

| In-person conferences | 35% |

| Roundtable discussions | 33% |

| Other (please specify) | 7% |