Policy on Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods (2023): Control measures

Control measures to meet the Table 1 microbiological criteria for L. monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods

On this page

- Control of ready-to-eat food manufacturing

- Environmental sampling (Figures 2, 3 and 4) and testing

- Sampling and testing of ready-to-eat foods (Table 1)

- Importance of trend analysis

Control of ready-to-eat food manufacturing

RTE food manufacturers should have effective GMPs in place and be able to demonstrate that their food safety system controls L. monocytogenes in RTE foods in order to meet the microbiological criteria specified in Table 1. As incoming raw ingredients may contain L. monocytogenes, RTE food manufacturers should consider developing supply-chain controls on raw ingredients (for example, a formal agreement with the suppliers, Certificate of Analysis, GAP certification), and applying validated processing steps that would eliminate or reduce numbers of L. monocytogenes.

RTE food manufacturers should be aware that the following factors influence the potential for the introduction of L. monocytogenes in the post-process areas where foods are exposed to the environment prior to packaging (CAC, 2009a):

- infrastructure

- plant layout (for example, traffic control, separation of equipment and utensils between raw and RTE areas)

- equipment design and maintenance (for example, equipment that require disassembly, such as slicing equipment)

- effectiveness of sanitation practices

- employee training and practices

This is managed through the implementation of GMPs, including adequate sanitation practices. Rigorous adherence to GMPs is essential due to the potential presence of Listeria spp. in the environment, with their ability to spread and thrive in the processing environment (Farber et al., 2021). As such, a multi-facetted approach should be used to prevent persistence of Listeria spp. via the physical disruption of biofilms and application of sanitizers which may need to be rotated, as applicable (Spanu and Jordan, 2020; Mazaheri et al., 2021). In addition, sanitation management can lead to innovations and sanitary design improvement (for example, equipment, facility).

Several scientific publications are available on how to minimize the presence of Listeria in RTE food manufacturing environments (Tompkin et al., 1999; Zoellner et al., 2019; Spanu and Jordan, 2020). In addition, workshops and documents developed by food industry trade associations on current best practices for the control of L. monocytogenes in RTE foods and the implementation of environmental monitoring programs within specific segments of the industry are also accessible. These resources may represent good supplementary information for RTE food manufacturers.

Furthermore, RTE food manufacturers should conduct on-site observation to assess adherence to GMPs that can influence the presence of Listeria spp. in the food processing environment (CAC, 2009a). Keeping in mind that the presence of Listeria spp. is an indicator of the potential presence of L. monocytogenes, it is not possible to predict, by visual observation alone, the degree to which Listeria spp. may occur in areas where RTE foods are exposed both before and during final packaging. An effective environmental monitoring program, supported by investigative sampling to detect sources of Listeria spp., should be used to identify additional steps the manufacturer should take to continuously improve its food safety system. Experience indicates that environmental sampling is the most sensitive tool to verify the effectiveness of control measures to prevent the introduction of L. monocytogenes into RTE foods (Tompkin et al., 1992; Tompkin, 2002; Farber et al., 2021).

Process control

Increased knowledge of the ecology of L. monocytogenes in RTE foods has clarified the categories of foods in which the growth of L. monocytogenes can or will not occur. Some RTE food manufacturers may also use food additives to control L. monocytogenes throughout the shelf-life of a food (see Appendix C). Although food additives have a long history of use against foodborne pathogens by limiting their growth or by reducing their numbers, manufacturers should confirm that the specific use of a food additive is permitted in Canada and validate its efficacy in the food under consideration. Furthermore, food processing aids and post-packaging treatments can also be used to eliminate or reduce numbers of L. monocytogenes in RTE foods (see Appendix C).

Environmental sampling (Figures 2, 3 and 4) and testing

Steps should be taken to reduce the potential for the introduction of L. monocytogenes into RTE foods by addressing Listeria spp. in the food processing environment. It is important that RTE food manufacturers are able to demonstrate that their food safety system will prevent L. monocytogenes from establishing itself in their manufacturing facilities by performing environmental sampling and testing. Risk-based frequency details are left to the discretion of the relevant regulatory authority (CFIA, 2023). The presence of Listeria spp. in a RTE food plant indicates that GMPs may be inadequate, as it suggests the potential presence of L. monocytogenes in the environment or the food. Any observation of the inadequate implementation of GMPs that could lead to the introduction of L. monocytogenes into a RTE food should trigger a review of the manufacturer's process and procedures. This review should also take into account environmental and end-product test results.

If Listeria spp. are found in the environment, RTE food manufacturers should conduct investigative sampling to determine their origin, following Figures 2 to 4, below. Investigative sampling differs from the routine environmental sampling used to monitor the control of Listeria spp. It involves collecting additional samples from different sites to help identify more clearly the potential sources of Listeria spp. Investigative sampling is an indispensable approach for identifying and eliminating harbourage sites (Tompkin, 2002; CAC, 2009a). RTE food manufacturers should identify and eliminate potential sources of Listeria spp. (for example, root cause analysis) by performing process review, environmental sampling and end-product testing. Furthermore, if the review indicates that Listeria spp. are not being controlled (for example, processing conditions that cannot eliminate Listeria spp. in the raw materials, an inadequate food safety system that cannot eliminate Listeria spp. from the post-process environment), this should be taken as evidence for the need to improve control measures. RTE food manufacturers should respond, in a timely manner, to all positive environmental test results, with appropriate corrective actions.

The expected steps to be undertaken by RTE food manufacturers when sampling both food contact surfaces (FCSs), that is, any surface or object that comes into contact with RTE foods, and non-FCSs, that is, any surface or object that does not come into contact with RTE foods, and testing for Listeria spp., are outlined in this section. The steps indicated in Figures 2 to 4 represent the minimum sampling and testing recommended by Health Canada. Manufacturers can exceed these minimum recommendations. Health Canada's Compendium of Analytical Methods lists methods that have been accepted for use in the administration of the Food and Drugs Act and Regulations (Health Canada, 2021a). Details on environmental sampling are described in method MFLP-41 (Health Canada, 2010). Methods and laboratory procedures for the analytical testing of environmental samples for Listeria spp. can also be found in the compendium. Industry should confirm that the 'application' section of the method is appropriate for the intended purpose.

It is important to perform environmental sampling in post-process areas where foods are exposed to the environment prior to packaging since positive results could be indicative of the potential presence of L. monocytogenes. Verifying that the processing environment is free from Listeria spp. (that is, reduced to below detectable levels) is the key to producing safe RTE foods.

A risk-based approach should be used in designing an environmental monitoring program. The environment of the following foods should be monitored and sampled at greater frequencies:

- food that is specifically produced for consumption by vulnerable populations

- food in which the growth of L. monocytogenes to levels exceeding 100 CFU/g can occur throughout the stated shelf-life

- food that does not contain L. monocytogenes inhibitors

- food that is not subjected to a post-packaging treatment before distribution

The specifics of an environmental sampling plan should be determined based on the probability that finding a Listeria spp. positive site could be indicative of the introduction of L. monocytogenes into RTE foods. One approach to consider such probability is by dividing the plant into different zones (ICMSF, 2018a; Simmons and Wiedmann, 2018; Spanu and Jordan, 2020). With the zone concept, Zone 1 would represent the highest probability for the introduction of L. monocytogenes into RTE foods and Zone 4 would represent the lowest probability for the introduction of L. monocytogenes into RTE foods. Zone 1 would include FCSs where RTE foods are exposed to the environment prior to packaging. Zone 2 would include non-FCSs in proximity to Zone 1 (for example, control panels adjacent to FCSs). Zone 3 would be further from the packaging area, but within the processing area (for example, floor drains, walls). Zone 4 would be located outside the processing and packaging areas (for example, outside of the area where RTE foods are exposed, such as loading docks, locker rooms and cafeterias). It would be expected that more environmental samples be taken from Zones 1 and 2, while Zones 3 and 4 may be sampled at a lower frequency.

The environmental monitoring program should be sufficiently robust regarding sampling selection, frequency of sampling, number of samples, method of sampling and so on to enable both RTE food manufacturers and the relevant regulatory authority to conclude, when reviewing data, that the foods being produced are safe (CAC, 2009a; CAC, 2020).

Food contact surfaces

Each RTE food manufacturer should have an environmental monitoring program that has been designed to assess the effectiveness of control measures, including sanitation and other GMPs, as well as the potential for the introduction of L. monocytogenes into RTE foods. Environmental monitoring programs should include routine sampling of FCSs that come into contact with exposed RTE foods prior to packaging. Such samples should be collected during production, typically after 3 hours of operation. The use of sponges or swabs to sample the surface areas of equipment is recommended. Examples of FCSs include: chill brines, containers, racks for transportation, conveyor belts, slicers, dicers, shredders, blenders, tables and equipment used to assemble/package foods, packaging equipment, hand tools, gloves, aprons, metal surfaces with gaps (for example, bad welding), food residue sites and other hard to clean areas (Health Canada, 2010).

Furthermore, additional sampling may be conducted immediately before start-up, to verify the effectiveness of sanitation. As part of their verification activities, RTE food manufacturers may find testing for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) bioluminescence or aerobic colony/plate count (ACC or APC) to be useful for this purpose. However, these methods cannot be used to replace testing for Listeria spp.

The number of sites (for example, 1 to 10) tested will vary according to the complexity of the processing system and packaging line. The frequency and points for routine sampling should be plant and line-specific, based on the manufacturing processes and control measures present (Tompkin et al., 1992; Zoellner et al., 2018). Samples should also be collected from non-FCSs as an additional measure of monitoring and verification. An increase in sampling sites (FCSs and non-FCSs), as well as the frequency of sampling, should be considered both during and after special circumstances (for example, construction, the installation or modification of equipment, overhead/ceiling leaks in exposed food areas), since these activities may lead to a loss of L. monocytogenes control in the food processing area (Tompkin, 2002; Spanu and Jordan, 2020). RTE food manufacturers should consider seeking expert technical advice to customize the best approach for their environmental sampling.

One of the goals of the Listeria policy is to encourage RTE food manufacturers to perform robust environmental sampling on a regular basis and to perform trend analysis on their results to detect problems that need corrective actions. Figures 2 and 3 below are reflective of the risk the RTE food may pose to consumers if L. monocytogenes is present. RTE food manufacturers should respond as soon as possible to all positive FCS test results, with appropriate follow-up actions, including corrective actions (see the section on Corrective actions for positive test results of food contact surfaces and non-food contact surfaces, below) and investigative sampling (as per Figures 2 and 3). These actions should take into account the type and location of the sampling sites, as well as the category of food. At a minimum, the FCSs in the routine monitoring program should be included when re-sampling. In some situations, food in various stages of processing or product build-up can be used as additional FCS samples to further assess the presence of Listeria spp. along a production line or system. Furthermore, if FCS samples are found positive at 2 (Figure 2) or more (Figure 3) steps, end-product testing should be performed.

Testing for Listeria spp. and reacting to positive results as if they were L. monocytogenes provides for a more sensitive and broader environmental monitoring program than would testing for L. monocytogenes alone (Farber et al., 2021). Nevertheless, if manufacturers choose to test FCSs for L. monocytogenes instead of Listeria spp., it is recommended that individual lots of food produced at the time of FCS sampling be held pending results from this testing. End-product testing for L. monocytogenes should be performed if L. monocytogenes is detected on a FCS (Figures 2 and 3, below).

Persistence of Listeria spp. on food contact surfaces

In a situation where 2 or more FCS samples from the same production line (that is, using the same equipment) are found positive for Listeria spp. within a short timeframe, such a situation is considered to be potential evidence of persistence and an indication that the food safety system (for example, GMPs, sanitation practices) may be inadequate to prevent the establishment of Listeria spp. in the food processing environment. This short timeframe is operation-specific. It will vary based on factors such as production volume, production seasonality and testing frequency.

RTE food manufacturers should respond as soon as possible with appropriate follow-up actions, including corrective actions (see the section on Corrective actions for positive test results of food contact surfaces and non-food contact surfaces, below) and investigative sampling. Investigative sampling will assist in finding and eliminating the source of Listeria spp., particularly if there is a harbourage site from which Listeria spp. or a specific subtype of L. monocytogenes is repeatedly isolated (CAC, 2009a). These actions should take into account the type and location of the sampling sites, as well as the category of food. This information should be communicated as soon as possible to the relevant regulatory authority.

Non-food contact surfaces

Environmental monitoring programs should also include routine sampling of non-FCSs. Examples of non-FCSs include: drains, standing water, cracks in floors and walls, smokehouses, floors in heavily-trafficked areas, tires on fork-lift trucks, foot and wheel baths that are in poor condition, high-pressure hoses, cleaning tools (mops, squeegees, brushes and so on), trash cans, under-side of conveyor belts, hollow rollers, roller guards, bearings, chill tanks, refrigerators, cold rooms, ice makers, overhead pipes, drip pans, wet insulation, maintenance tools, dust from construction and air filtration equipment (Health Canada, 2010).

It is important to perform follow-up actions (including corrective actions, see the section below) when non-FCSs test positive for Listeria spp. (Figure 4, below). In general, detection of Listeria spp. from non-FCSs, including L. monocytogenes, usually precedes their detection from FCSs (Tompkin et al., 1999; D'Amico and Donnelly, 2008). Accordingly, identifying sources of Listeria spp. away from the production line and preventing their transfer within the food processing environment is a fundamental principle of Listeria control. It should be noted that the sampling sites selected after the completion of corrective actions may differ from those assessed during routine monitoring. Upon re-sampling, the original or nearby sites might be negative, but other sites might reveal a positive, and hence be informative in resolving the problem. Positive test results collected over time can also be used to determine a trend. A review of data from trend analysis would indicate whether the RTE food manufacturer is properly controlling Listeria (see the section on Importance of trend analysis, below).

Corrective actions for positive test results of food contact surfaces and non-food contact surfaces

RTE food manufacturers should respond as soon as possible to all positive FCS and non-FCS test results for Listeria spp. (Figures 2 to 4, below) with appropriate corrective actions. These may include the following:

- increasing or correcting sanitation procedures

- intensified cleaning and sanitizing beyond FCSs, including equipment disassembly

- verification of cleaning and sanitizing procedures

- intense cleaning and sanitizing of the surrounding areas

- modification of equipment for improved cleanability

- performing additional sampling (Figures 2 to 4)

- timely re-testing of the positive sites

- testing of RTE foods that were potentially in contact with positive FCSs

- obtaining additional data to confirm hypotheses when conducting root cause analysis

- developing and implementing an investigative sampling plan (for the affected line and possibly the food)

- in-depth review of the RTE food manufacturer's food safety system (for example, HACCP plan) and making necessary changes to reduce the potential for the introduction of L. monocytogenes in the post-process areas where foods are exposed to the environment prior to packaging (see the section on Control of ready-to-eat food manufacturing, above)

Corrective actions should be monitored to confirm their effectiveness. All of this information should be documented and integrated into the RTE food manufacturer's trend analysis (see the section on Importance of trend analysis, below).

RTE food manufacturers should attempt to determine the potential sources of Listeria spp. by means of process review, environmental sampling (including investigative sampling) and end-product testing.

- With the zone concept, Zone 1 includes FCSs where RTE foods are exposed to the environment prior to packaging. The number of meaningful sampling sites (10 recommended) selected on each processing line should depend upon the complexity of the lines. Details on environmental sampling are described in method MFLP-41 (Health Canada, 2010).

- If analyzing FCS samples as composites, a maximum of 10 FCS samples should be combined.

- The 'application' section of the method should be appropriate for the intended purpose (for example, MFHPB and MFLP methods; Health Canada, 2021a).

- The records should include information on corrective actions, investigative sampling, end-product testing and risk management actions (for example, disposition of product).

- Investigative sampling will assist in finding and eliminating the source of Listeria spp., particularly if there is a harbourage site from which Listeria spp. or a specific subtype of L. monocytogenes is repeatedly isolated.

- At a minimum, the FCS sites in the routine monitoring program should be included. The number and location of samples should be adequate to verify that the entire line is negative and under control.

- A qualitative method for L. monocytogenes (that is, a detection method using enrichment) should be used for end-product testing. Recognized methods for end-product testing can be found in the Compendium of Analytical Methods (Health Canada, 2021a).

Note 1: The steps indicated in this figure represent the minimum sampling and testing recommended by Health Canada. RTE food manufacturers can exceed these minimum recommendations.

Note 2: End-product testing for L. monocytogenes should be performed if L. monocytogenes is detected on a FCS.

Figure 2 - Text description

Figure 2 outlines the sampling guidelines for food contact surfaces, Category 1 ready-to-eat foods and Category 2 ready-to-eat foods specifically produced for consumption by vulnerable populations.

Step A is the starting point for Category 1 ready-to-eat foods produced for consumption by vulnerable populations and the general population. It is also the starting point for Category 2 ready-to-eat foods produced for consumption by vulnerable populations:

Food contact surface samples should be collected. With the zone concept, Zone 1 includes food contact surfaces where ready-to-eat foods are exposed to the environment prior to packaging. The number of meaningful sampling sites, 10 is recommended, selected on each processing line should depend upon the complexity of the lines. Details on environmental sampling are described in method MFLP-41 by Health Canada, 2010. Analysis of 10 food contact surface samples should be conducted, either separately or as composites. If analyzing food contact surface samples as composites, a maximum of 10 food contact surface samples should be combined. Recognized methods for testing food contact surfaces for Listeria spp. can be found in the Compendium of Analytical Methods. The 'application' section of the method should be appropriate for the intended purpose, for example, MFHPB and MFLP methods by Health Canada, 2021a.

If no food contact surface sample is positive for Listeria spp., the routine monitoring program should be continued.

Alternatively, if a food contact surface sample is positive for Listeria spp., step B should be initiated.

Step B:

Starting at this step and beyond, all activities and data should be recorded in a file that is maintained separately from the routine monitoring program. The records should include information on corrective actions, investigative sampling, end-product testing and risk management actions, for example, the disposition of product. Corrective actions should be initiated as soon as possible. After corrective actions are applied, investigative sampling should be performed as this will assist in finding and eliminating the source of Listeria spp., particularly if there is a harbourage site from which Listeria spp. or a specific subtype of L. monocytogenes is repeatedly isolated. Thereafter, all products from that line should be placed on hold. Food contact surface samples should be collected to verify effectiveness of corrective actions. At a minimum, the food contact surface sites in the routine monitoring program should be included. The number and location of samples should be adequate to verify that the entire line is negative and under control. The food contact surface samples should be analyzed separately. Recognized methods for testing food contact surfaces for Listeria spp. can be found in the Compendium of Analytical Methods. The 'application' section of the method should be appropriate for the intended purpose, for example, MFHPB and MFLP methods by Health Canada, 2021a.

If no food contact surface sample is positive for Listeria spp., the routine monitoring program should be resumed and products put on hold at step B may be released.

Alternatively, if a food contact surface sample is positive for Listeria spp., end-product testing should be pursued. All lots of food that were on hold should be tested as per Table 1: 'Sampling methodologies and microbiological criteria for Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods'. If L. monocytogenes is detected in 125 g of food, the relevant regulatory authority should be consulted about risk management actions, for example, the disposition of product. If L. monocytogenes is not detected in 125 g of food, an assessment should be performed and consultation with the relevant regulatory authority is strongly recommended.

In parallel with end-product testing, step C should be initiated.

Step C:

It is strongly recommended that food businesses notify the relevant regulatory authority as soon as possible. Intensified corrective actions should be initiated as soon as possible and investigative sampling should continue to be performed. Investigative sampling will assist in finding and eliminating the source of Listeria spp., particularly if there is a harbourage site from which Listeria spp. or a specific subtype of L. monocytogenes is repeatedly isolated. Food contact surface samples and their associated end-product samples should be collected. At a minimum, the food contact surface sites in the routine monitoring program should be included. The number and location of samples should be adequate to verify that the entire line is negative and under control. Then, food contact surface samples should be analyzed separately and end-product should be tested as per Table 1: 'Sampling methodologies and microbiological criteria for Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods'. The collection of food contact surface samples and their associated end-product samples, as well as their testing, should be repeated until L. monocytogenes is not detected in end-product samples and the associated food contact surface samples are negative for Listeria spp., for 3 or more consecutive productions days. The 'application' section of the method should be appropriate for the intended purpose, for example, MFHPB and MFLP methods by Health Canada, 2021a. A qualitative method for L. monocytogenes, that is, a detection method using enrichment, should be used for end-product testing. Recognized methods for end-product testing can be found in the Compendium of Analytical Methods by Health Canada, 2021a. Once food contact surface and end-product samples are negative for 3 or more consecutive productions days, the routine monitoring program should be resumed and products put on hold may be released. If however, any food contact surface sample is positive for Listeria spp. or L. monocytogenes is detected in any end-product sample, the previous corrective actions should be reviewed and all other potential options should be considered. Investigative sampling and root cause analysis should also be continued. The 'application' section of the method should be appropriate for the intended purpose, for example, MFHPB and MFLP methods by Health Canada, 2021a. A qualitative method for L. monocytogenes, that is, a detection method using enrichment, should be used for end-product testing. Recognized methods for end-product testing can be found in the Compendium of Analytical Methods by Health Canada, 2021a. It is strongly recommended that food businesses review all results with the relevant regulatory authority.

Note 1: The steps indicated in Figure 2 represent the minimum sampling and testing recommended by Health Canada. Ready-to-eat food manufacturers can exceed these minimum recommendations.

Note 2: End-product testing for L. monocytogenes should be performed if L. monocytogenes is detected on a food contact surface.

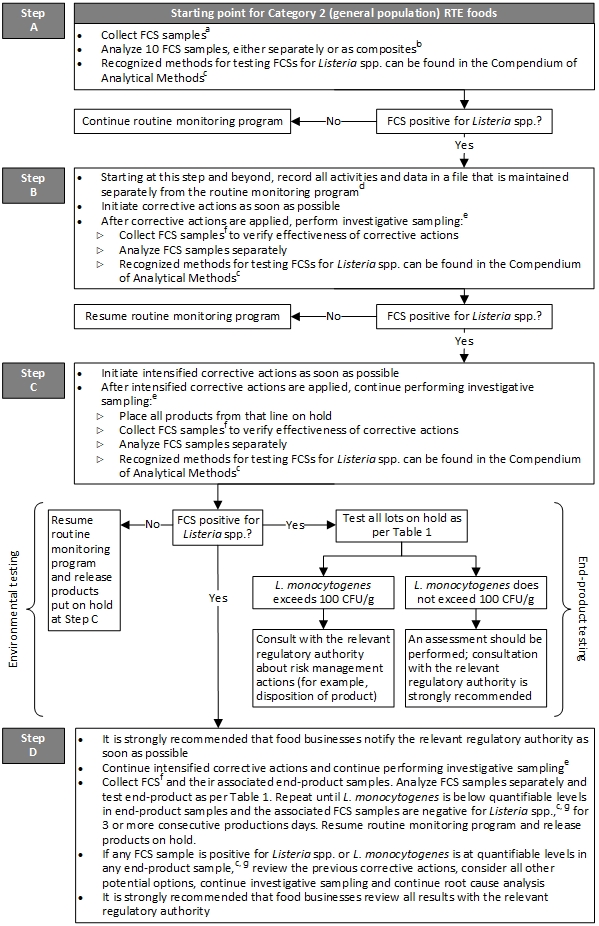

- With the zone concept, Zone 1 includes FCSs where RTE foods are exposed to the environment prior to packaging. The number of meaningful sampling sites (10 recommended) selected on each processing line should depend upon the complexity of the lines. Details on environmental sampling are described in method MFLP-41 (Health Canada, 2010).

- If analyzing FCS samples as composites, a maximum of 10 FCS samples should be combined.

- The 'application' section of the method should be appropriate for the intended purpose (for example, MFHPB and MFLP methods; Health Canada, 2021a).

- The records should include information on corrective actions, investigative sampling, end-product testing and risk management actions (for example, disposition of product).

- Investigative sampling will assist in finding and eliminating the source of Listeria spp., particularly if there is a harbourage site from which Listeria spp. or a specific subtype of L. monocytogenes is repeatedly isolated.

- At a minimum, the FCS sites in the routine monitoring program should be included. The number and location of samples should be adequate to verify that the entire line is negative and under control.

- A quantitative method for L. monocytogenes (that is, an enumerative method done by direct plating onto selective agar) should be used for end-product testing. Recognized methods for end-product testing can be found in the Compendium of Analytical Methods (Health Canada, 2021a).

Note 1: The steps indicated in this figure represent the minimum sampling and testing recommended by Health Canada. RTE food manufacturers can exceed these minimum recommendations.

Note 2: End-product testing for L. monocytogenes should be performed if L. monocytogenes is detected on a FCS.

Figure 3 - Text description

Figure 3 outlines the sampling guidelines for food contact surfaces and Category 2 ready-to-eat foods produced for consumption by the general population.

Step A is the starting point for Category 2 ready-to-eat foods produced for consumption by the general population:

Food contact surface samples should be collected. With the zone concept, Zone 1 includes food contact surfaces where ready-to-eat foods are exposed to the environment prior to packaging. The number of meaningful sampling sites, 10 is recommended, selected on each processing line should depend upon the complexity of the lines. Details on environmental sampling are described in method MFLP-41 by Health Canada, 2010. Analysis of 10 food contact surface samples should be conducted, either separately or as composites. If analyzing food contact surface samples as composites, a maximum of 10 food contact surface samples should be combined. Recognized methods for testing food contact surfaces for Listeria spp. can be found in the Compendium of Analytical Methods. The 'application' section of the method should be appropriate for the intended purpose, for example, MFHPB and MFLP methods by Health Canada, 2021a.

If no food contact surface sample is positive for Listeria spp., the routine monitoring program should be continued.

Alternatively, if a food contact surface sample is positive for Listeria spp., step B should be initiated.

Step B:

Starting at this step and beyond, all activities and data should be recorded in a file that is maintained separately from the routine monitoring program. The records should include information on corrective actions, investigative sampling, end-product testing and risk management actions, for example, the disposition of product. Corrective actions should be initiated as soon as possible. After corrective actions are applied, investigative sampling should be performed as this will assist in finding and eliminating the source of Listeria spp., particularly if there is a harbourage site from which Listeria spp. or a specific subtype of L. monocytogenes is repeatedly isolated. Thereafter, food contact surface samples should be collected to verify effectiveness of corrective actions. At a minimum, the food contact surface sites in the routine monitoring program should be included. The number and location of samples should be adequate to verify that the entire line is negative and under control. The food contact surface samples should be analyzed separately. Recognized methods for testing food contact surfaces for Listeria spp. can be found in the Compendium of Analytical Methods. The 'application' section of the method should be appropriate for the intended purpose, for example, MFHPB and MFLP methods by Health Canada, 2021a.

If no food contact surface sample is positive for Listeria spp., the routine monitoring program should be resumed.

Alternatively, if a food contact surface sample is positive for Listeria spp., step C should be initiated.

Step C:

Intensified corrective actions should be initiated as soon as possible. After intensified corrective actions are applied, investigative sampling should continue to be performed as this will assist in finding and eliminating the source of Listeria spp., particularly if there is a harbourage site from which Listeria spp. or a specific subtype of L. monocytogenes is repeatedly isolated. Thereafter, all products from that line should be placed on hold. Food contact surface samples should be collected to verify effectiveness of corrective actions. At a minimum, the food contact surface sites in the routine monitoring program should be included. The number and location of samples should be adequate to verify that the entire line is negative and under control. The food contact surface samples should be analyzed separately. Recognized methods for testing food contact surfaces for Listeria spp. can be found in the Compendium of Analytical Methods. The 'application' section of the method should be appropriate for the intended purpose, for example, MFHPB and MFLP methods by Health Canada, 2021a.

If no food contact surface sample is positive for Listeria spp., the routine monitoring program should be resumed and products put on hold at step C may be released.

Alternatively, if a food contact surface sample is positive for Listeria spp., end-product testing should be pursued. All lots of food that were on hold should be tested as per Table 1: 'Sampling methodologies and microbiological criteria for Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods'. If L. monocytogenes exceeds 100 colony forming units per gram in a food sample, the relevant regulatory authority should be consulted about risk management actions, for example, the disposition of product. If L. monocytogenes does not exceed 100 colony forming units per gram in a food sample, an assessment should be performed and consultation with the relevant regulatory authority is strongly recommended.

In parallel with end-product testing, step D should be initiated.

Step D:

It is strongly recommended that food businesses notify the relevant regulatory authority as soon as possible. Intensified corrective actions and investigative sampling should continue to be performed. Investigative sampling will assist in finding and eliminating the source of Listeria spp., particularly if there is a harbourage site from which Listeria spp. or a specific subtype of L. monocytogenes is repeatedly isolated. Food contact surface samples and their associated end-product samples should be collected. At a minimum, the food contact surfaces sites in the routine monitoring program should be included. The number and location of samples should be adequate to verify that the entire line is negative and under control. Food contact surface samples should be analyzed separately and end-product should be tested as per Table 1: 'Sampling methodologies and microbiological criteria for Listeria monocytogenes in ready-to-eat foods'. The collection of food contact surface samples and their associated end-product samples, as well as their testing, should be repeated until L. monocytogenes is below quantifiable levels in end-product samples and the associated food contact surface samples are negative for Listeria spp., for 3 or more consecutive productions days. The 'application' section of the method should be appropriate for the intended purpose, for example, MFHPB and MFLP methods by Health Canada, 2021a. A quantitative method for L. monocytogenes, that is, an enumerative method done by direct plating onto selective agar, should be used for end-product testing. Recognized methods for end-product testing can be found in the Compendium of Analytical Methods by Health Canada, 2021a. Once L. monocytogenes is below quantifiable levels in end-product samples and the associated food contact surface samples are negative for Listeria spp. for 3 or more consecutive production days, the routine monitoring program should be resumed and products put on hold may be released. If however, any food contact surface sample is positive for Listeria spp. or L. monocytogenes is at quantifiable levels in any end-product sample, the previous corrective actions should be reviewed and all other potential options should be considered. Investigative sampling and root cause analysis should also be continued. The 'application' section of the method should be appropriate for the intended purpose, for example, MFHPB and MFLP methods by Health Canada, 2021a. A quantitative method for L. monocytogenes, that is, an enumerative method done by direct plating onto selective agar, should be used for end-product testing. Recognized methods for end-product testing can be found in the Compendium of Analytical Methods by Health Canada, 2021a. It is strongly recommended that food businesses review all results with the relevant regulatory authority.

Note 1: The steps indicated in Figure 3 represent the minimum sampling and testing recommended by Health Canada. Ready-to-eat food manufacturers can exceed these minimum recommendations.

Note 2: End-product testing for L. monocytogenes should be performed if L. monocytogenes is detected on a food contact surface.

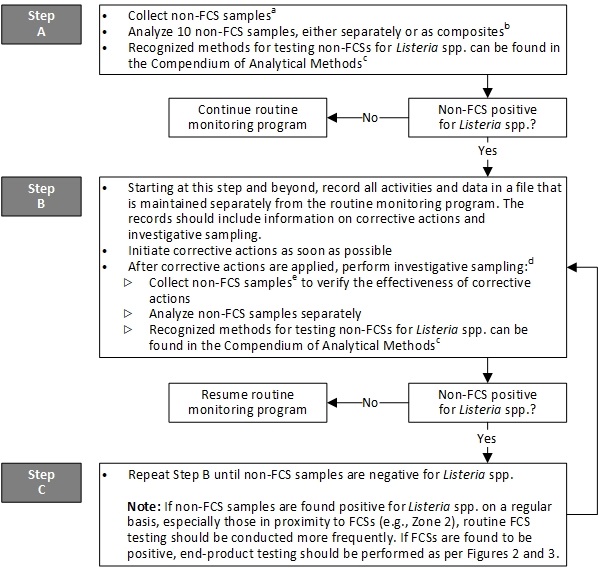

- With the zone concept, Zones 2, 3 and 4 include non-FCSs. The number of meaningful sampling sites (10 recommended) selected in the plant should depend upon the complexity of the plant. Details on environmental sampling are described in method MFLP-41 (Health Canada, 2010).

- If analyzing non-FCS samples as composites, a maximum of 10 non-FCS samples should be combined.

- The 'application' section of the method should be appropriate for the intended purpose (for example, MFHPB and MFLP methods; Health Canada, 2021a).

- Investigative sampling will assist in finding and eliminating the source of Listeria spp., particularly if there is a harbourage site from which Listeria spp. or a specific subtype of L. monocytogenes is repeatedly isolated.

- The sampling sites may differ after completing corrective actions. Upon re-sampling, the original or nearby sites might be negative but sampling other sites might reveal a positive, and hence be informative in resolving the problem.

Note: The steps indicated in this figure represent the minimum sampling and testing recommended by Health Canada. RTE food manufacturers can exceed these minimum recommendations.

Figure 4 - Text description

Figure 4 outlines the sampling guidelines for non-food contact surfaces, especially those in proximity to food contact surfaces.

Step A:

Non-food contact surface samples should be collected. With the zone concept, Zones 2, 3 and 4 include non-food contact surfaces. The number of meaningful sampling sites, 10 is recommended, selected in the plant should depend upon the complexity of the plant. Details on environmental sampling are described in method MFLP-41 by Health Canada, 2010. Analysis of 10 non-food contact surface samples should be conducted, either separately or as composites. If analyzing non-food contact surface samples as composites, a maximum of 10 non-food contact surface samples should be combined. Recognized methods for testing non-food contact surfaces for Listeria spp. can be found in the Compendium of Analytical Methods. The 'application' section of the method should be appropriate for the intended purpose, for example, MFHPB and MFLP methods by Health Canada, 2021a.

If no non-food contact surface sample is positive for Listeria spp., the routine monitoring program should be continued.

Alternatively, if a non-food contact surface sample is positive for Listeria spp., step B should be initiated.

Step B:

Starting at this step and beyond, all activities and data should be recorded in a file that is maintained separately from the routine monitoring program. The records should include information on corrective actions and investigative sampling. Corrective actions should be initiated as soon as possible. After corrective actions are applied, investigative sampling should be performed as this will assist in finding and eliminating the source of Listeria spp., particularly if there is a harbourage site from which Listeria spp. or a specific subtype of L. monocytogenes is repeatedly isolated. Thereafter, non-food contact surface samples should be collected to verify effectiveness of corrective actions. The sampling sites may differ after completing corrective actions. Upon re-sampling, the original or nearby sites might be negative but sampling other sites might reveal a positive, and hence be informative in resolving the problem. Non-food contact surface samples should be analyzed separately. Recognized methods for testing non-food contact surfaces for Listeria spp. can be found in the Compendium of Analytical Methods. The 'application' section of the method should be appropriate for the intended purpose, for example, MFHPB and MFLP methods by Health Canada, 2021a.

If no non-food contact surface sample is positive for Listeria spp., the routine monitoring program should be resumed.

Alternatively, if a non-food contact surface sample is positive for Listeria spp., step B should be repeated until non-food contact surface samples are negative for Listeria spp. If non-food contact surface samples are found positive for Listeria spp. on a regular basis, especially those in proximity to food contact surfaces, for example, in Zone 2, routine food contact surface testing should be conducted more frequently. If food contact surfaces are found to be positive, end-product testing should be performed as per Figures 2 and 3.

Note: The steps indicated in Figure 4 represent the minimum sampling and testing recommended by Health Canada. Ready-to-eat food manufacturers can exceed these minimum recommendations.

Sampling and testing of ready-to-eat foods (Table 1)

When manufacturing RTE foods, rigorous adherence to GMPs (with a focus on adequate sanitation) coupled with environmental monitoring (that is, implementation of an appropriate environmental sampling plan; Figures 2 to 4, above) is the most desirable approach to control Listeria in the food processing environment. Relying on the results of environmental testing will allow for better decision-making regarding the release of RTE foods, rather than relying solely on end-product testing. Accordingly, microbiological testing of food that results in no detection of L. monocytogenes may not portray the true overall microbiological condition of the food, as in general, testing gives only very limited information on the safety status of a food. This is due to, among other things, the non-uniform distribution of bacteria, such as L. monocytogenes, within a food (ICMSF, 2018b).

Nonetheless, end-product testing can be informative and is conducted for many different reasons, for example:

- as part of the Listeria environmental monitoring program (for example, evaluation of end-product when FCSs test positive for Listeria spp., as stipulated in Figures 2 and 3, above)

- periodic testing to verify the process or the effectiveness of control measures to prevent the introduction of L. monocytogenes into RTE foods

- verification of the effectiveness of food additives or food processing aids

- performing trend analysis

- regulatory compliance

- customer requirements

- foreign country requirements

- testing of foods sampled at various points in distribution, including retail, as part of surveillance or food safety investigation activities (for example, testing of previously distributed lots where continued exposure is expected)

Moreover, end-product testing for L. monocytogenes should be performed if L. monocytogenes is detected on a FCS (see the section on Environmental sampling and testing; Figures 2 and 3, above).

When testing RTE foods, food businesses should develop and implement:

- written procedures for end-product testing with details on any hold and test procedures

- sampling procedures

- specifics of sampling frequency and size

- methodologies to be used for testing (details regarding methodological approaches are left to the discretion of the relevant regulatory authority (CFIA, 2023))

- follow-up actions

It is recommended that individual lots of food being tested be held pending results from testing, as specified in Table 1, below. Any test results for L. monocytogenes in a RTE food, at levels exceeding those specified in Table 1, should be addressed immediately by the food business. It is strongly recommended that food businesses communicate this information as soon as possible to the relevant regulatory authority having jurisdiction over risk management actions.

Samples of RTE foods submitted for the testing of L. monocytogenes should consist of 5 sample units of at least 100 g or mL each (Table 1, below), taken at random, and should be representative of the lot and the production conditions. In the case where individual lots cannot be differentiated by clear product markings or if the food business is unable to provide information that would allow for the differentiation of individual lots, then the entire day's production or the whole shipment would be considered as a single lot.

Ready-to-eat foods specifically produced for consumption by vulnerable populations

Irrespective of category, a qualitative method for L. monocytogenes (that is, a detection method using enrichment) should be used for end-product testing of RTE foods specifically produced for consumption by vulnerable populations. Recognized methods, such as MFHPB-30 (Pagotto et al., 2011a), can be found in the Compendium of Analytical Methods (Health Canada, 2021a). Industry should confirm that the 'application' section of the method is appropriate for the intended purpose. An analytical sample size of 5 × 25 g for these RTE foods should be used and analyzed separately or as a composite, as specified in Table 1, below.

When L. monocytogenes is detected in RTE foods specifically produced for consumption by vulnerable populations, the food business should start an investigation to determine whether potentially unsafe food has left its control and if so, the extent of distribution (for example, retail level, consumer level). It is also important to try to determine the source of L. monocytogenes, where its introduction has occurred and the lots involved. Investigative sampling will assist in finding and eliminating the source of Listeria spp., particularly if there is a harbourage site (Figure 2, above; CAC, 2009a). The food business should take action on identified unsafe lots of food. The investigation may reveal that previous or subsequent lots produced under the same conditions may be impacted and may represent a health concern. In such situations, risk management actions may be needed. More specifically, the detection of L. monocytogenes in these RTE foods should trigger immediate follow-up by the food business as described in steps B and C of Figure 2. It is strongly recommended that food businesses communicate this information as soon as possible to the relevant regulatory authority having jurisdiction over risk management actions.

Category 1 ready-to-eat foods

A qualitative method for L. monocytogenes (that is, a detection method using enrichment) should be used for end-product testing of Category 1 RTE foods. Recognized methods, such as MFHPB-30 (Pagotto et al., 2011a), can be found in the Compendium of Analytical Methods (Health Canada, 2021a). Industry should confirm that the 'application' section of the method is appropriate for the intended purpose. An analytical sample size of 5 × 25 g for these RTE foods should be used and analyzed separately or as a composite, as specified in Table 1, below.

When L. monocytogenes is detected in a Category 1 RTE food, the food business should start an investigation to determine whether potentially unsafe food has left its control and if so, the extent of distribution (for example, retail level, consumer level). It is also important to determine the source of L. monocytogenes, where its introduction has occurred and the lots involved. Investigative sampling will assist in finding and eliminating the source of Listeria spp., particularly if there is a harbourage site (Figure 2, above; CAC, 2009a). The food business should take action on identified unsafe lots of food. The investigation may reveal that previous or subsequent lots produced under the same conditions may be impacted and may represent a health concern. In such situations, risk management actions may be needed. More specifically, the detection of L. monocytogenes in these RTE foods should trigger immediate follow-up by the food business as described in steps B and C of Figure 2. It is strongly recommended that food businesses communicate this information as soon as possible to the relevant regulatory authority having jurisdiction over risk management actions.

Category 2 (2A and 2B) ready-to-eat foods

A quantitative method for L. monocytogenes (that is, an enumerative method done by direct plating onto selective agar) should be used for end-product testing of Category 2 RTE foods. Recognized methods, such as MFLP-74 (Pagotto et al., 2011b), can be found in the Compendium of Analytical Methods (Health Canada, 2021a). Industry should confirm that the 'application' section of the method is appropriate for the intended purpose. An analytical sample size of 5 × 10 g for this specific category of RTE food should be used and each analytical unit should be analyzed separately, as specified in Table 1, below.

When levels of L. monocytogenes exceed 100 CFU/g in a Category 2 RTE food, the food business should start an investigation to determine whether potentially unsafe food has left its control and if so, the extent of distribution (for example, retail level, consumer level). It is also important to try to determine the source of L. monocytogenes, where its introduction has occurred and the lots involved. Investigative sampling will assist in finding and eliminating the source of Listeria spp., particularly if there is a harbourage site (Figure 3, above; CAC, 2009a). The food business should take action on identified unsafe lots of food. The investigation may reveal that previous or subsequent lots produced under the same conditions may be impacted and may represent a health concern. In such situations, risk management actions may be needed.

More specifically, regardless of the L. monocytogenes levels in a Category 2 RTE food, immediate follow-up should be triggered by the food business as described in steps C and D of Figure 3, as well as in the section on Follow-up actions to positive ready-to-eat food test results, below. It is strongly recommended that food businesses communicate this information as soon as possible to the relevant regulatory authority having jurisdiction over risk management actions. The presence of L. monocytogenes at levels between 5 and 100 CFU/g in a Category 2 RTE food, occurring repeatedly at brief intervals, is likely an indication of an inadequate food safety system unable to control L. monocytogenes.

Follow-up actions to positive ready-to-eat food test results

Any RTE food that yields a positive test result for L. monocytogenes must lead to corrective actions by the food business, such as:

- recalling food (that is, removing implicated foods from further sale or use, at any point in the supply chain)

- initiating investigative sampling

- initiating additional end-product testing

- initiating a review of the food safety system

| Ready-to-eat (RTE) food category (intended consumers) | Sampling | Analysis | End-product testing | Action level for L. monocytogenes | Level of concern | Level of priorityFootnote b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Any category (vulnerable populations) Category 1 (general population) |

5 sample units (min 100 g or ml each), which are representative of the lot and the production conditions, taken aseptically at random from each lot | 5 × 25 g analytical units,Footnote e analyzed either separately or com-posited | Detec-tion | Detected in 125 gFootnote f, Footnote g | Health Risk 1Footnote h | High |

Category 2A (general population) A number of factors will be taken into consideration with regards to which foods may fall into this Category, that is, (1) RTE foods which are known to occasionally contain low levels of L. monocytogenes and their processing does not involve any heat treatment (based on validation); (2) RTE refrigerated foods with a stated shelf-life of 5 days or less. Such foods could include fresh-cut fruits and vegetables. Category 2B (general population) |

5 sample units (min 100 g or ml each), which are representative of the lot and the production conditions, taken aseptically at random from each lot | 5 × 10 g analytical units,Footnote e analyzed separately | Enumer-ation | > 100 CFU/gFootnote i, Footnote j | Health Risk 2Footnote h, Footnote k | Medium to low |

Note: If insufficient, inadequate or no information exists regarding the Category 2A or 2B categorization of the RTE food, it will be considered as a Category 1 RTE food. As such, the sampling and testing methodologies for Category 1 RTE foods, as specified in Table 1, should be used. Should questions arise regarding food categorization, the RTE manufacturer should be able to demonstrate in which category the RTE food falls. In cases where validation was conducted for categorization, the manufacturer should have documentation of adequate validation studies substantiating that L. monocytogenes cannot grow or that the RTE food will only support limited growth of L. monocytogenes to ≤ 100 CFU/g throughout the stated shelf-life.

|

||||||

Importance of trend analysis

As previously stated, RTE food manufacturers should not rely solely on end-product testing to verify their control measures for L. monocytogenes. The manufacturer's food safety system should use modern quality control and statistical methods to monitor the process and the effectiveness of control measures. This will allow for the detection of spatial-temporal patterns suggestive of sources of L. monocytogenes, particularly harbourage sites that may then be further investigated and eliminated (Zoellner et al., 2018). Data obtained from trend analysis can be modelled and used to verify control measures, as well as to assess environmental monitoring activities and to better target compliance activities. It is important to note that negative results, if due to an inappropriate sampling methodology, can lead to a false sense of safety. Positive findings should be viewed as the successful identification of an issue that should lead to follow-up actions, including corrective actions (Spanu and Jordan, 2020). Where possible, quality control and statistical methods should include modern graphical techniques (for example, control charts, Pareto diagrams). All data should be made available to individuals responsible for managing and overseeing the implementation and verification of control measures for L. monocytogenes. Responsibility for updating and disseminating the data should be assigned to 1 or more individuals within the organization (for example, quality assurance, food safety or HACCP coordinators).

On going review and analysis of the data for Listeria spp. collected during routine monitoring, as well as from investigative sampling, should be performed to detect trends prior to the development of major issues. Such reviews should also provide information on the prevalence of Listeria spp. and its fluctuation over time. They also serve to identify issues that should be addressed in a timely manner. Attention should be given to the dates and locations of positive samples to determine whether low-level or sporadic positive samples occur at particular locations that may have gone previously unnoticed (CAC, 2009a). The use of the zone concept for environmental monitoring can be useful for early detection of Listeria spp. on non-FCSs to help prevent their transfer to FCSs (see the section on Environmental sampling and testing, above). In situations where there is evidence of persistence (see the section on Persistence of Listeria spp. on food contact surfaces, above), molecular characterization techniques such as whole-genome sequencing may help during root cause analysis to identify harbourage sites (persistence) or transient Listeria spp. in the food processing environment. As more information becomes available from trend analysis, it should be used to achieve improved control of Listeria as the RTE food manufacturer gains experience and makes necessary adjustments to its food safety system.