ARCHIVED – 2020 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration

For the period ending

December 31, 2019

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

ISSN 1706-3329

Table of Contents

- Message from the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship

- A Snapshot of Immigration to Canada in 2019

- Introduction

- Why immigration is important to Canada

- Temporary resident programs and volumes

- Permanent immigration to Canada

- Francophone immigration outside Quebec

- Canada’s next permanent resident immigration levels plan

- Gender and diversity considerations in immigration

- Annex 1: Section 94 and Section 22.1 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

- Annex 2: Tables

- Annex 3: Temporary Migration Reporting

- Annex 4: Ministerial Instructions in 2019

Message from the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship

Canada continues to be a safe and welcoming destination for immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers. Immigrants enrich Canada beyond measure, and no accounting of our progress over the last century and a half is complete without including the contributions of newcomers. Even as we adjust to the extraordinary challenge of the COVID-19 pandemic, we cannot lose sight of the enormous benefits immigration presents to our prosperity and way of life. Newcomers bring their heritage and culture, but also their talent, ideas and perspectives.

Immigrant selection programs administered by the Department continued to grow and innovate in 2019. Much of the growth came from established programs administered through Express Entry and in partnership with provinces through their Provincial Nominee Programs. Moreover, the Department has continued to introduce innovative new programs to make it easier for newcomers to make contributions in specific communities throughout the country. For example, the Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot launched in 2019 to focus economic immigration in Canada’s rural and northern centres. Similarly, the Department has been working to make the Atlantic Immigration Pilot a permanent offering that can respond to the particular labour market needs in that region. For specific economic sectors – caregivers and agri-food – the Department also introduced new pathways to permanent residency to test and meet needs in these critical areas.

The Department’s first-rate selection and settlement programs respond effectively to the large numbers of people seeking a new life and new opportunities in Canada. In 2019, we welcomed over 341,000 permanent residents, including 30,000 resettled refugees. Over 402,000 study permits and 404,000 temporary work permits were also issued.

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada continued to provide a number of supports for refugees in Canada in 2019, including temporary health-care coverage, income support, housing assistance and language training. For newcomers, the ability to communicate in their new home is a huge priority. With an investment of $7.6 million over 4 years, the Department selected seven organizations to provide intensive language training to newcomers in Francophone communities.

I am very proud to note as well that the Department has put considerable effort into improving outcomes for vulnerable individuals. In 2019, specific measures were introduced to help migrant workers in abusive job situations, newcomers experiencing family violence, caregivers seeking permanent residency and LGBTI refugees. Canada continued its international leadership in providing and encouraging other countries to create additional protection spaces for the most vulnerable.

Over the past year, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada has worked tirelessly to provide hope and opportunity to so many people in need, while supporting the diversity and prosperity of Canadian communities. As we respond to the significant challenges of 2020, the Department continues to be focused on delivering the best possible services to Canadians and foreign nationals wanting to come to Canada.

To learn about the Department’s achievements in greater detail, I invite you to read the 2020 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration.

Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship

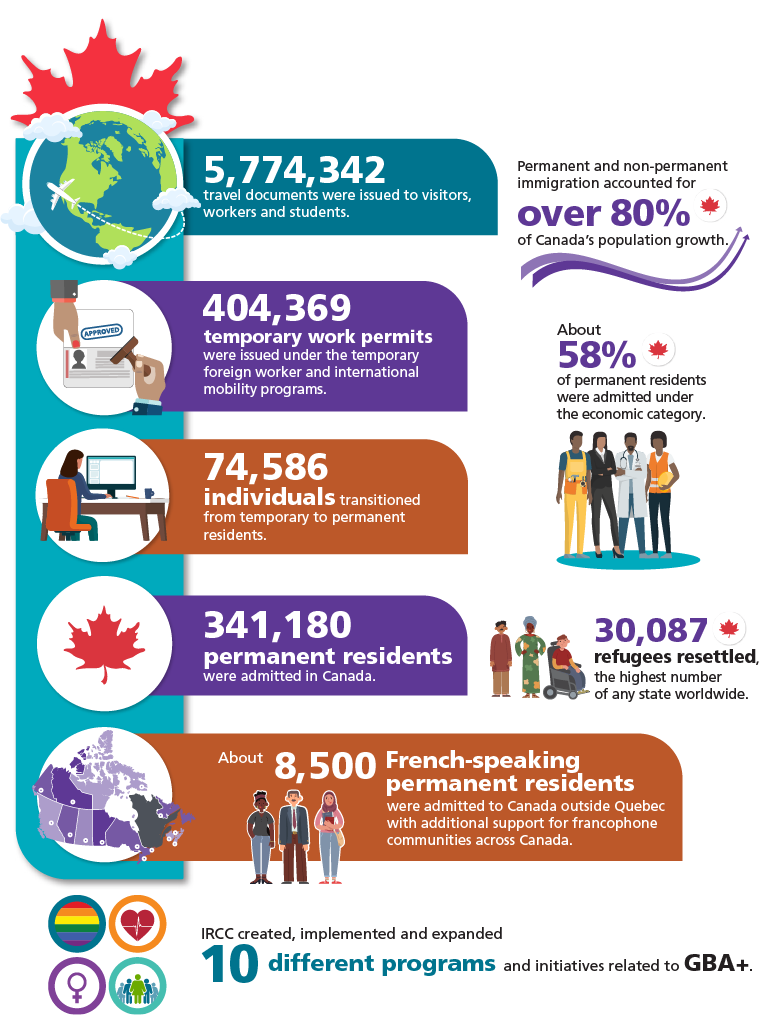

A Snapshot of Immigration to Canada in 2019

Text version: A Snapshot of Immigration to Canada in 2019

- 5,774,342 travel documents were issued to visitors, workers and students.

- 404,369 temporary work permits were issued under the temporary foreign worker and international mobility programs.

- 74,586 individuals transitioned from temporary to permanent residents.

- 341,180 permanent residents were admitted in Canada.

- About 8,500 French-speaking permanent residents were admitted to Canada outside Quebec with additional support for francophone communities across Canada.

- IRCC created, implemented, and expanded 10 different programs and initiatives related to GBA+.

- Permanent and non-permanent immigration accounted for over 80% of Canada’s population growth.

- About 58% of permanent residents admitted under the economic category.

- 30,087 refugee resettled, the highest number of any state worldwide.

Introduction

The Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration provides the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship with the opportunity to inform Parliament and Canadians of key highlights and related information on immigration to Canada. While this report on immigration and its tabling in Parliament is a requirement of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), it also serves to offer key information on the successes that have been achieved in welcoming newcomers to Canada.

This report sets out information and statistical details regarding temporary resident volumes and permanent resident admissions. It also provides the planned number of upcoming permanent resident admissions. In addition, this report contextualizes the efforts undertaken with provinces and territories in our shared responsibility of immigration, highlights certain aspects of Francophone immigration and ends with an analysis of gender and diversity considerations in Canada’s approach to immigration.

While the 2020 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration focuses on immigration results that were achieved in 2019, publication takes place in the following calendar year to allow Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) the opportunity to obtain final information from the preceding calendar year.

About the data in this report

Admissions data can be found in Annexes 2 and 3, as well as on the Government of Canada’s Open data portal and in the facts and figures published by IRCC.

Data in this report that were derived from IRCC sources may differ from those reported in other publications; these differences reflect typical adjustments to IRCC’s administrative data files over time. As the data in this report are taken from a single point in time, it is expected that they will change slightly as additional information becomes available.

Why immigration is important to Canada

For over a century, immigration has been a means to support population, economic, and cultural growth in Canada. Millions of eligible people from around the world have chosen to reside in Canada and make it their new home. Whether seeking better economic opportunities, reuniting with family members, or seeking protection as resettled refugees or other protected persons, newcomers to Canada have been a major source of ongoing growth and prosperity.

Along with those who migrate to Canada permanently, many individuals come to Canada to stay temporarily, whether as a visitor, international student or a temporary foreign worker. Regardless of their pathway into Canada, they all contribute in a meaningful way to Canada’s economy, support the success and growth of various industries, and contribute to Canada’s diversity and multiculturalism.

Immigration has helped to build the country that the world sees today – a diverse society with strong economic and social foundations, and with continued potential for further growth and prosperity.

Immigration supports Canada’s demographic and economic growth

Immigration will continue to be a key driver in advancing Canada’s economy, especially in the context of low birth rates and its vital role in growing the working age population, and it will remain so into the future. By the early 2030s, it is expected that Canada’s population growth will rely exclusively on immigration.Footnote 1 It is also important to note that many source countries for Canada’s immigration system face similar demographic challenges related to aging populations and lower birth rates.Footnote 2 As a result, Canada must be prepared to compete internationally for young, skilled and mobile workers.

Between 2017 and 2018, net immigration accounted for 80% of Canada’s population increase, with the remaining 20% accounted for through natural increase.Footnote 3 Canada's population growth between 2018 and 2019, at 1.4%, was the highest rate of growth among G7 nations.Footnote 4 This increase (over 531,000 people) was overwhelmingly driven (82%) by the arrival of immigrants and non-permanent residents.Footnote 5

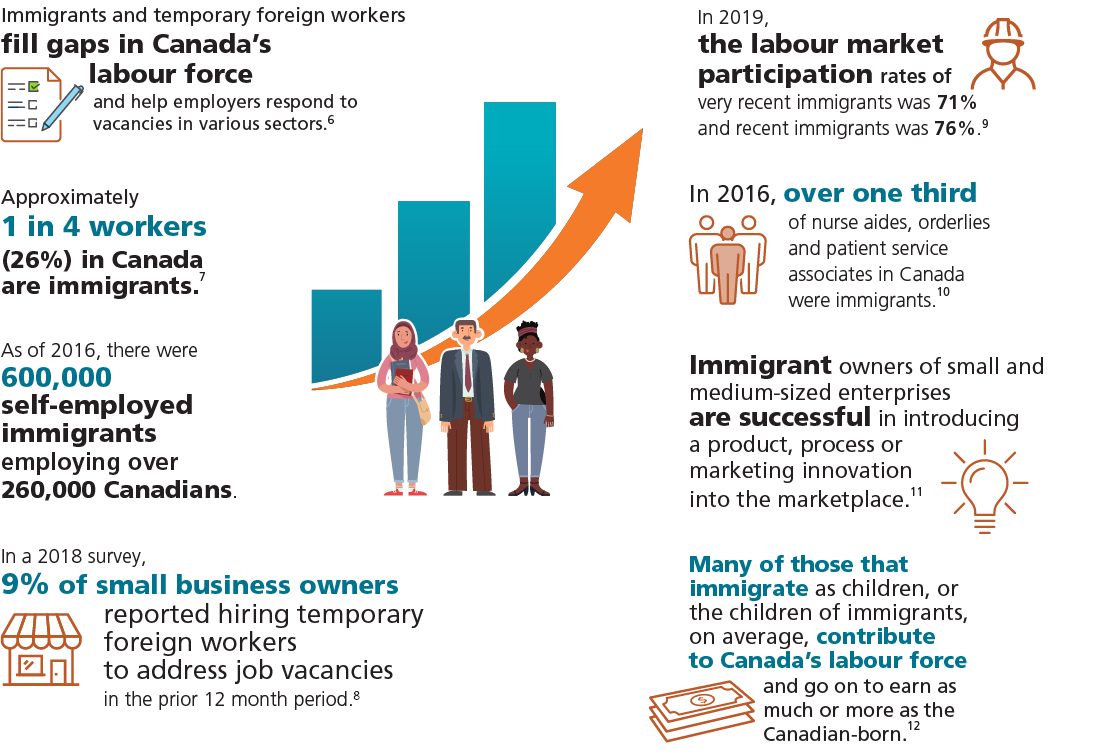

Immigrants and newcomers contribute to economic growth

Text version: Immigrants and newcomers contribute to economic growth

Immigrants and temporary foreign workers fill gaps in Canada’s labour force and help employers respond to vacancies in various sectors.Footnote 6

Approximately 1 in 4 workers (26%) in Canada are immigrants.Footnote 7

As of 2016, there were 600,000 self-employed immigrants employing over 260,000 Canadians.

In a 2018 survey, 9% of small business owners reported hiring temporary foreign workers to address job vacancies in the prior 12-month period.Footnote 8

In 2019, the labour market participation rates of very recent immigrants was 71% and recent immigrants was 76%.Footnote 9

In 2016, over one third of nurse aides, orderlies and patient service associates in Canada were immigrants.Footnote 10

Immigrant owners of small and medium-sized enterprises are successful in introducing a product, process or marketing innovation into the marketplace.Footnote 11

Many of those that immigrate as children, or the children of immigrants, on average, contribute to Canada’s labour force and go on to earn as much or more as the Canadian-born.Footnote 12

Investing in the next generation of Canadian business leaders

Dhillon School of Business

When wildfires raged through Alberta in 2016, Bob Dhillon felt compelled to help those forced from their homes and communities. Having immigrated to Canada with his family as refugees in the 1970s, Bob understood the immense emotional and financial burden of being displaced from one’s home.

Bob generously offered 3 months of free rent in 200 of his residential units in Edmonton, Calgary and Saskatoon to help hundreds of evacuees in their time of need.

A real estate mogul with a philanthropic nature, Bob believes that his success comes with an immense responsibility to give back to a community and country that have given him so much. Bob came to Canada during his teenage years, having fled a brutal civil war in Liberia. Bob’s parents worked in the real estate business, so real estate had always been part of his DNA.

Bob credits his success, in part, to living in a country that provides him with the freedom and opportunity to pursue his passions, one of which is education. In 2018, Bob pledged a $10-million gift to the University of Lethbridge, the largest donation in the institution’s history. In recognition of this generous contribution, the University renamed its Faculty of Management the Dhillon School of Business.

Bob believes that “education and innovation are critical to the continued success of Canada”, which is why he is shaping the next generation of Canadian business leaders. His involvement in curriculum development and his hands-on approach are helping the business school turn into a major hub of innovation.

For more success stories, see #ImmigrationMatters on the IRCC website.

Immigrants and newcomers contribute to the advancement of Canadian society

Since Canada’s inception in 1867, the Canadian identity has been formed by the diverse cultures, religions, histories and languages of English, French and the Indigenous Peoples. Immigration has also played a key role in advancing Canada’s tradition of bringing diverse peoples together to live within the same national community. Immigrants to Canada come from many source countries and possess a wide variety of cultural and religious backgrounds, and are able to integrate effectively in communities across the country.Footnote 13 In 2016, immigration originating from Africa surpassed European immigration, and this trend continued in 2019. Each wave of immigration contributes to the growing ethnic, linguistic, and religious diversity in Canada. In turn, Canadians have typically welcomed immigrants to Canada as highly educated, ambitious and capable people with the potential to contribute positively to Canadian society.Footnote 14

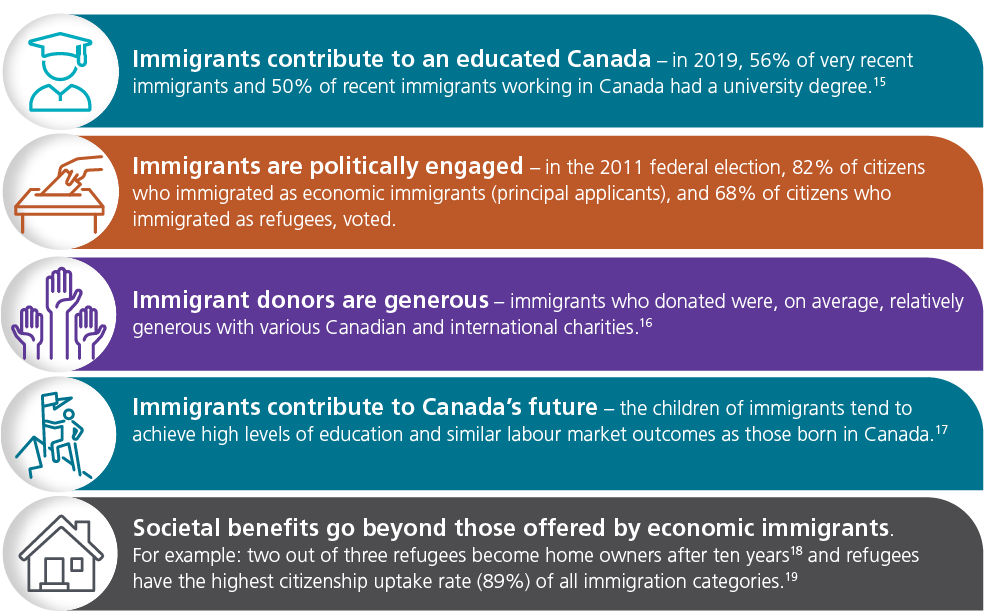

Immigrants and newcomers contribute to the advancement of Canadian society

Text version: Immigrants and newcomers contribute to the advancement of Canadian society

Immigrants contribute to an educated Canada – in 2019, 56% of very recent immigrants and 50% of recent immigrants working in Canada had a university degree.Footnote 15

Immigrants are politically engaged – in the 2011 federal election, 82% of citizens who immigrated as economic immigrants (principal applicants), and 68% of citizens who immigrated as refugees, voted.

Immigrant donors are generous – immigrants who donated were, on average, relatively generous with various Canadian and international charities.Footnote 16

Immigrants contribute to Canada’s future – the children of immigrants tend to achieve high levels of education and similar labour market outcomes as those born in Canada.Footnote 17

Societal benefits go beyond those offered by economic immigrants. For example: two out of three refugees become home owners after ten yearsFootnote 18 and refugees have the highest citizenship uptake rate (89%) of all immigration categories.Footnote 19

“Angel of the North” delivering her third generation of babies

Dr. Lalita Malhotra

Measuring the societal impact of immigration in Canada is not always best told by facts and figures. Sometimes it is better told by the many personal stories of newcomers who bring rich and diverse experiences to Canada and contribute in ways that perhaps only they could.

Dr. Lalita Malhotra, an obstetrician and gynecologist originally from Delhi, India, has been in Canada since 1975. She and her husband, a pediatrician, first arrived in Ontario, afterwards moving to Prince Albert, Saskatchewan.

Becoming established in Prince Albert’s medical community was challenging. Dr. Malhotra started her own practice, and it grew by word of mouth.

Over time, Dr. Malhotra built such trust and admiration among her clients that Indigenous elders recently bestowed her with a traditional Star Blanket, considered their highest form of honour. She has also been awarded the Order of Saskatchewan and the Order of Canada, and was proclaimed Citizen of the Year in Prince Albert in 2008. Alongside her medical practice, she is a volunteer presiding official at citizenship ceremonies.

For more success stories, see #ImmigrationMatters on the IRCC website.

Immigration programs contribute to the growth of Canadian communities

The Government of Canada offers several economic immigration programs that attract a broad range of talented people to contribute to communities across the country, some of which are listed below.

There were 68,647 people selected through the Provincial Nominee Program in 2019, the highest number since the program’s launch. This represents over 20% of all permanent resident admissions and directly supports provinces and territories with meeting their labour market needs.

In 2019, the Department continued to work in partnership with the Atlantic provinces to enhance the effectiveness of the Atlantic Immigration Pilot, an employer- and retention-driven approach to respond to the economic development and labour needs of Atlantic Canada. The Government of Canada has committed to transition this pilot program into a permanent Atlantic immigration program.

Testing a new community-based economic development approach, IRCC launched the Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot in 2019 to support smaller and more remote communities to access the economic benefits of immigration. It helps Canadian communities offer meaningful employment, with the goal of retaining newcomers in the long term. Eleven communities were selected for this pilot and recommending candidates for permanent residence began in November 2019.

The three-year Agri-Food Pilot was launched on May 15, 2020, and provides a new pathway to permanent residence for experienced non-seasonal workers in specific agri-food industries and occupations. A total of 2,750 applicants and their family members can be accepted annually.

Consultations have begun with provinces, territories, and key stakeholders to design the new Municipal Nominee Program. The lessons learned from IRCC’s other economic pilots, notably the Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot, will also inform this new pathway to permanent residence.

The Economic Mobility Pathways Pilot has started to level the playing field so skilled refugees from around the world can autonomously access Canada’s economic immigration pathways without being at a disadvantage as a result of the circumstances of displacement. This allows refugees to highlight their skills and qualifications, in addition to their need for a permanent home.

Striking a chord in the community

Astrid Hepner with her saxophone

German-born Astrid moved to New York City in the 1990s, playing saxophone and working in the city’s busy recording industry for various companies, including the famous jazz label Blue Note Records. In 2005, she immigrated to Canada, settling in Hamilton with her daughter and her husband Darcy, who teaches music at Mohawk College.

“When I came to Hamilton I was impressed by its rich music scene, and as somebody who was new here, I wanted to contribute and be a part of it,” Astrid says. Since then, she has worked to expand and strengthen the music industry in Hamilton. In 2008, Astrid founded the Hamilton Music Collective and then used it to create An Instrument for Every Child (AIFEC) program.

AIFEC loans instruments and provides free music lessons to elementary school students who can’t afford the cost. Since its launch, it has involved some 5,000 students across 14 Hamilton schools and continues to expand.

For more success stories, see #ImmigrationMatters on the IRCC website.

The Government of Canada relies on its relationships with provinces, territories, and stakeholders to enable the success of its immigration system

Managing the successful implementation of Canada’s immigration programs requires collaboration with key stakeholders, including provinces, territories and other partners. In 2019, federal, provincial and territorial ministers responsible for immigration agreed to a joint vision for immigration, highlighting how newcomers contribute to building vibrant communities and an inclusive and prosperous Canada.

In 2019, IRCC engaged and sought perspectives from several sectors:

Text version: In 2019, IRCC engaged and sought perspectives from several sectors

- Academia

- Immigrant organization and not-for-profit organizations

- Francophone and official language minority communities

- Municipalities

- Provinces and territories and other government departments

- Employers and industry and sector councils

The success of Canada’s immigration programs is bolstered by a strong settlement sector. Through contribution agreements, IRCC funds service provider organizations across Canada (outside QuebecFootnote 20), including immigrant-serving agencies and social service organizations. Together, these organizations deliver a broad range of settlement services, which help newcomers to acquire knowledge about living and working in Canada, improve their official language skills, prepare for labour market entry, and form meaningful connections in their communities. The Department also funds service providers to deliver targeted resettlement supports to Government-Assisted Refugees and other eligible clients.

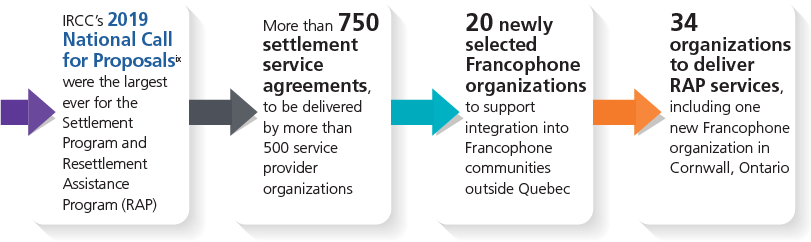

Text version: 2019 National Call for Proposals

IRCC’s 2019 National Call for Proposals were the largest ever for the Settlement Program and Resettlement Assistance Program (RAP)

More than 750 settlement service agreements, to be delivered by more than 500 service provider organizations

20 newly selected Francophone organizations to support integration into Francophone communities outside Quebec

34 organizations to deliver RAP services, including one new Francophone organization in Cornwall, Ontario

The Department’s settlement vision recognizes that successful integration requires a whole-of-society approach, including collaboration across all levels of government. In particular, provinces and territories fund their own settlement services and are responsible for sectors that are key to integration, including education, health and social services. As such, IRCC works closely with provinces and territories to advance shared interests and to ensure that investments in the Settlement Sector support coordinated and complementary service delivery.

Canada’s international leadership on migration and international protection

Not only does the federal government consult with domestic stakeholders, it also works closely with other countries and multilateral organizations to develop effective responses to the challenges and opportunities of global migration and refugee protection.

At the inaugural Global Refugee Forum in December 2019, Canada committed $50.4 million to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) to respond to the needs of refugees. Through its participation in the Forum, Canada demonstrated its steadfast commitment to remain engaged and at the forefront of exploring new and innovative solutions for refugee protection, marking the first major milestone in the implementation of the Global Compact on Refugees. History was also made by including a refugee advisor, Mr. Mustafa Alio, as a member of Canada’s Delegation and making a commitment to the ongoing inclusion of refugees.

In 2019, Canada continued its global leadership in international protection by resettling the highest number of refugees worldwide, for the second year in a row.

Canada’s leadership in refugee resettlement is supported by the Global Refugee Sponsorship Initiative, which aims to promote community sponsorship of refugees to increase refugee resettlement numbers worldwide. This initiative has led to the development of community sponsorship pilots and programs all over the world.

Canada also held the Chair of the Annual Tripartite Consultations on Resettlement in partnership with UNHCR and the Canadian Council for Refugees. In this capacity, Canada continued the tradition of facilitating open and frank dialogue while striving to produce positive outcomes by forging collaborative approaches to global resettlement. Emphasis was given to advancing the objectives of UNHCR’s Three-Year Strategy on Resettlement and Complementary Pathways. Canada also advocated for persons with lived refugee experience to be included in country delegations to key meetings related to the international refugee protection system.

Canada was the fifth largest financial contributor to the International Organization for Migration.Footnote 21

Looking ahead

COVID-19 has had a tremendous impact on Canada’s prosperity, including our economy. Despite these current challenges, immigration will continue to be a source of long-term economic growth in Canada. IRCC will continue to work with provinces and territories, and other partners and stakeholders, to ensure that our approach to immigration supports Canada’s ongoing prosperity.

Temporary resident programs and volumes

Visitors

Visitors to Canada, including tourists, business travelers, and other visitors must receive either a temporary resident visa (TRV) or an electronic travel authorization (eTA)Footnote 22 from IRCC before arrival in Canada. United States of America passport holders are exempt.

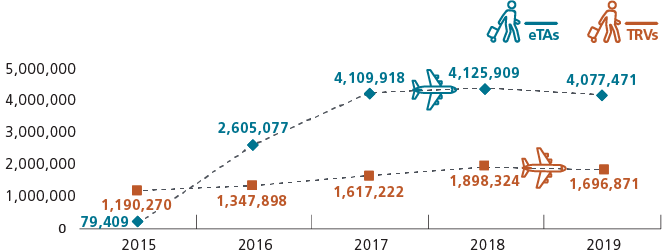

TRV and eTAs

Text version: TRV and eTAs

| Year | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eTAs | 79,409 | 2,605,077 | 4,109,918 | 4,125,909 | 4,077,471 |

| TRVs | 1,190,270 | 1,347,898 | 1,617,222 | 1,898,324 | 1,696,871 |

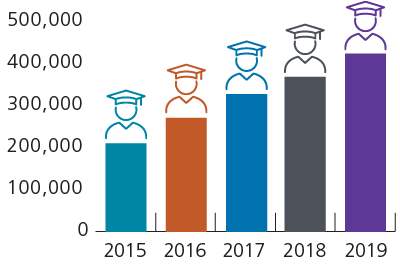

International students

International Student

Text version: International Student

| Year | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of international students permitted | 219,143 | 264,625 | 315,145 | 354,784 | 402,427 |

IRCC facilitates the entry of students who wish to study at a designated Canadian educational institution. Students approved to study in Canada are issued a study permit.

In 2019, 827,586 international students held valid study permits in Canada. Of these, 402,427 new study permits were issued (a 15% increase from 2018).

In 2019, 11,566 study permit holders were granted permanent residency.

When compared to other OECD countries, Canada had the 7th highest percentage of international students enrolled in post-secondary education in 2017.Footnote 23

International students contribute to Canada’s prosperity and have a greater impact on Canada’s economy than exports of auto parts, lumber or aircraft. In 2018, international students in Canada spent an estimated $21.6 billion on tuition and other expenses.Footnote 24

Temporary foreign workers

IRCC facilitates the entry of foreign nationals who seek temporary work in Canada.

In 2019, 98,310 individuals were issued work permits through the Temporary Foreign Worker Program and 306,797 individuals were issued a work permit under the International Mobility Program.Footnote 25 This represents an increase of almost 70,000 new permits from 2018.

Canada’s temporary immigration programs help Canadian businesses attract people with the talent they need to succeed in the global marketplace. Notably, the Global Skills Strategy supports Canadian business by providing a fast and reliable way to bring in the highly skilled foreign talent needed to succeed in the global marketplace when workers in Canada are unable to fill the need.

In 2019, 63,020 individuals with a temporary work permit were granted permanent residency.

Permanent immigration to Canada

In 2019, Canada achieved its highest level of permanent resident admissions in recent history with 341,180 admissions,Footnote 26 which is 6.3% higher than in 2018.

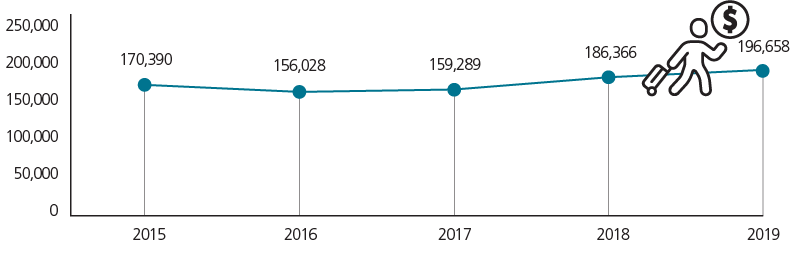

Economic immigration

The economic immigration class is the largest source of permanent resident admissions, at approximately 58% of all admissions in 2019.

In 2019, the number of individuals admitted to Canada under the Economic Class totalled 196,658, which is 5.5% higher than in 2018. This represents a record high number of admissions under this category.Footnote 27

Economic immigration

Text version: Economic immigration

| Year | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of economic immigrants permitted | 170,390 | 156,028 | 159,289 | 186,366 | 196,658 |

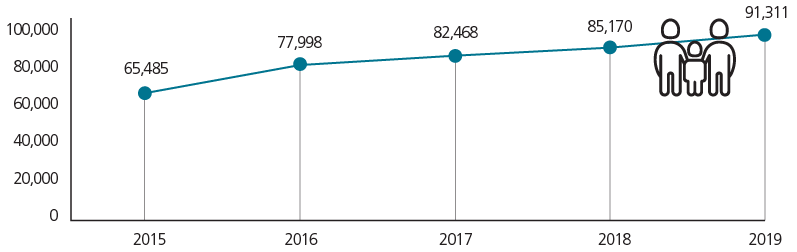

Family reunification

Family memberFootnote 28 of Canadian permanent residents and citizens may be sponsored to come to Canada as permanent residents. Sponsors accept financial responsibility for the individual for a defined period of time. In 2019, 91,311 individuals were admitted under this category, representing a 7.2% increase from 2018 and a record high.

Family reunification

Text version: Family reunification

| Year | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family Reunification Total | 65,485 | 77,998 | 82,468 | 85,170 | 91,311 |

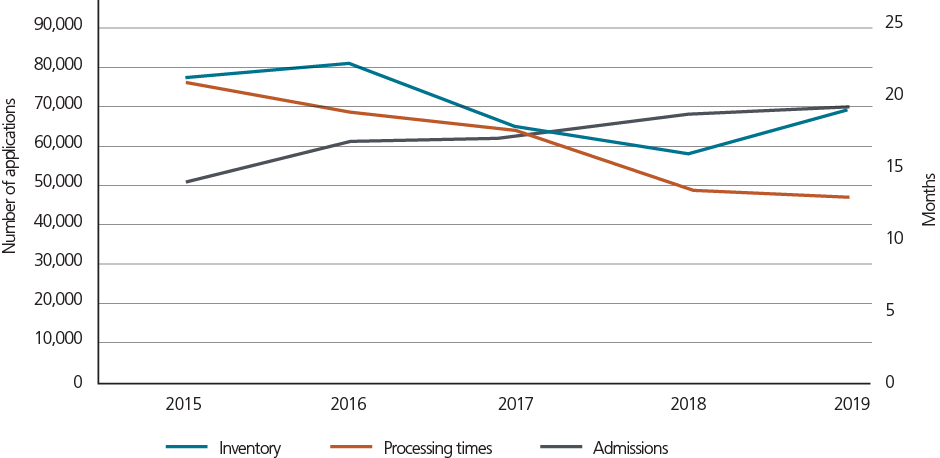

IRCC’s continued commitment to reduced processing times (the number of months in which 80% of complete applications are finalized by IRCC) and better management of the application inventory has resulted in faster reunification for families.

At the end of 2015, the backlog of applications for sponsored spouses, partners and children reached over 77,000 persons, with processing times of 21 months. The Department has since implemented a plan to reduce the inventory and start processing new applications within 12 months. This has resulted in reduced processing times for spouses, partners and children from 21 months in 2015 to 13 months by the end of 2019.Footnote 29

Spouse, Partners and Children

Text version: Spouse, partners and children

| Year | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processing time (months) | 21 | 19 | 18 | 14 | 13 |

| Admissions | 49,997 | 60,955 | 61,973 | 67,140 | 69,298 |

| Inventory | 77,278 | 80,571 | 66,348 | 58,031 | 68,473 |

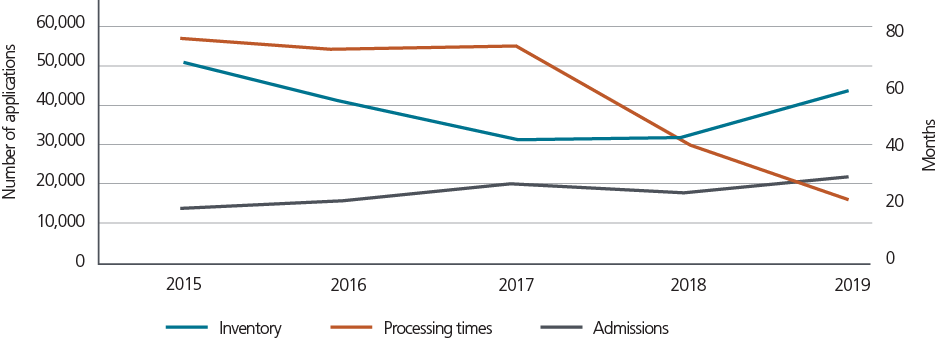

In 2019, 80% of parent and grandparent applications were processed within 19 months, down from 72 months in 2017 – progress achieved by reducing the inventory of applications since 2015 and managing the intake of new applications.

Parents and Grandparents

Text version: Parents and Grandparents

| Year | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processing time (months) | 74 | 71 | 72 | 40 | 19 |

| Admissions | 15,489 | 17,043 | 20,495 | 18,030 | 22,011 |

| Inventory | 50,661 | 40,511 | 32,165 | 32,411 | 43,666 |

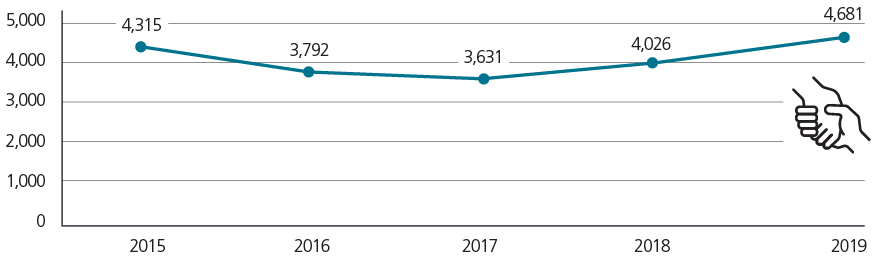

Humanitarian and compassionate immigration

Permanent residency may be granted based on humanitarian and compassionate grounds on a case-by-case basis, or certain public policy considerations under exceptional circumstances. In 2019, there were 4,681 permanent residents admitted through these discretionary streams.Footnote 30

Humanitarian and Compassionate

Text version: Humanitarian and Compassionate

| Year | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humanitarian and Compassionate | 4,315 | 3,792 | 3,631 | 4,026 | 4,681 |

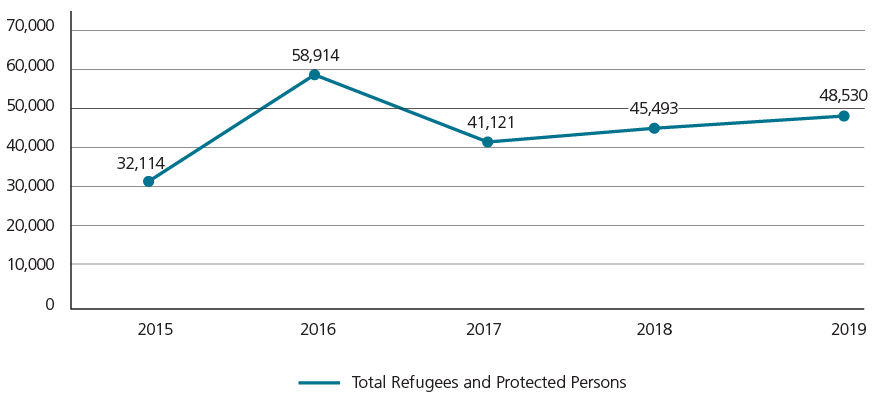

Refugees and protected persons

Refugees and Protected Persons

Text version: Refugees and Protected Persons

| Year | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Refugees and Protected Persons | 32,114 | 58,914 | 41,121 | 45,493 | 48,530 |

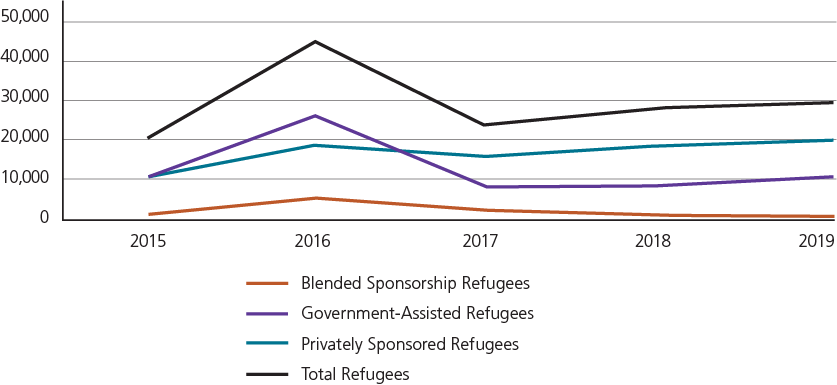

Refugees

Each year, IRCC facilitates the admission of a targeted number of permanent residents under the refugee resettlement category. IRCC offers protection to Convention Refugees, who are outside of their home country and are unable to return based on a well-founded fear of persecution due to race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group or political opinion.

Refugees

Text version: Refugees

| Year | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blended Sponsorship Refugee | 811 | 4,435 | 1,285 | 1,149 | 993 |

| Government-Assisted Refugee | 9,488 | 23,628 | 8,638 | 8,093 | 9,951 |

| Privately Sponsored Refugee | 9,747 | 18,642 | 16,699 | 18,568 | 19,143 |

| Total Refugees | 20,046 | 46,705 | 26,622 | 27,810 | 30,087 |

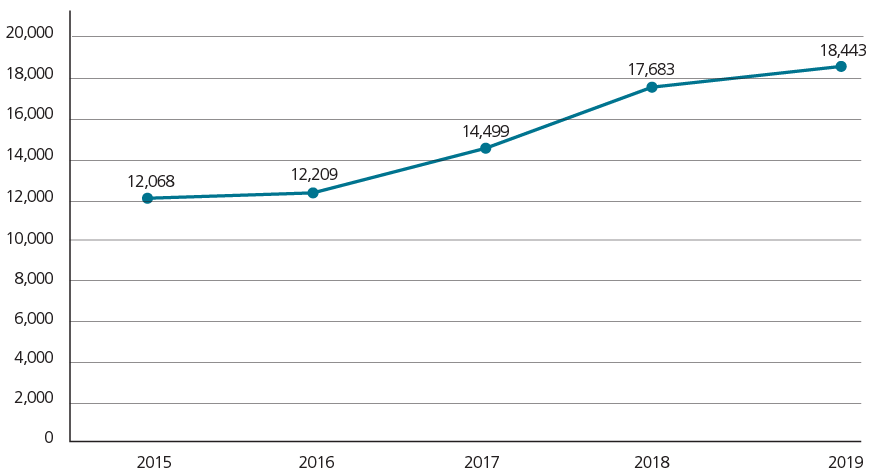

Protected Persons

IRCC provides support to protected persons and their dependants, who are asylum claimants granted protected status by Canada. In 2019, 18,443 individuals obtained permanent residence under the protected persons in Canada and dependents abroad category.

Protected persons and Dependants of Protected Persons

Text version: Protected persons and Dependants of Protected Persons

| Year | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protected Persons and Dependant of Protected Person | 12,068 | 12,209 | 14,499 | 17,683 | 18,443 |

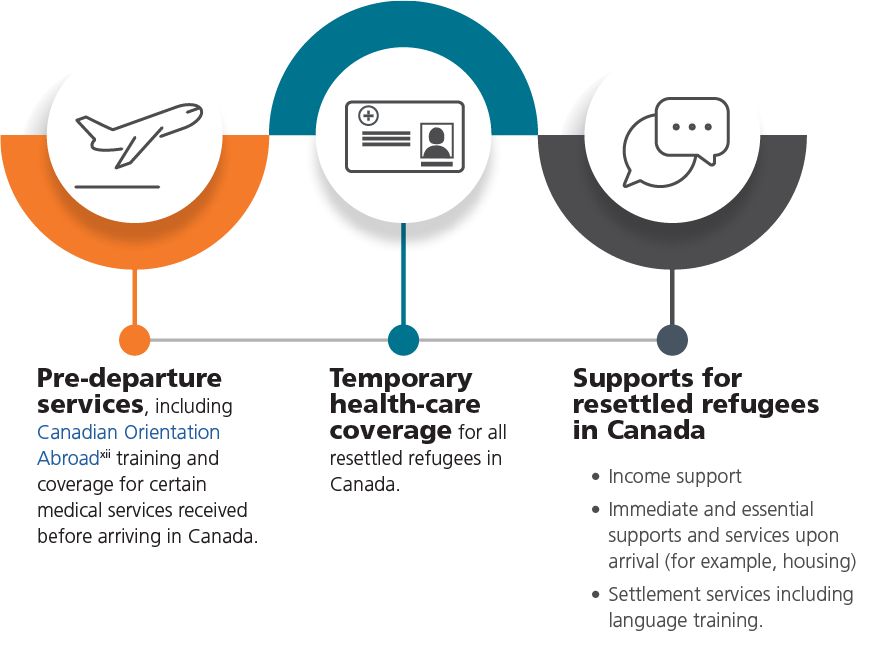

IRCC-funded programs provide supports and services to resettled refugees:

IRCC-funded programs provide supports and services to resettled refugees

Text version: IRCC-funded programs provide supports and services to resettled refugees

Pre-departure services, including Canadian Orientation Abroad training and coverage for certain medical services received before arriving in Canada.

Temporary health care coverage for all resettled refugees in Canada.

Supports for resettled refugees in Canada:

- Income support

- Immediate and essential supports and services upon arrival (for example, housing)

- Settlement services including language training.

Civil society and sponsorship organizations also provide critical settlement supports for privately sponsored refugees, including income support, assistance in securing housing, and ensuring access to language training and other refugee-support programs.

Asylum Claims

The in-Canada asylum system provides protection to foreign nationals when it is determined that they have a well-founded fear of persecution.

Canada received over 64,000 in-Canada asylum claims in 2019, the highest annual number received on record. Of these, approximately 26% were made by asylum claimants who crossed the Canada-U.S. border between designated ports of entry. The Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada finalized 43,004 claims in 2019. Further, Budget 2020 earmarked $795 million over five years to support continued processing of 50,000 asylum claims per year until 2023–2024. This investment builds on those made in Budgets 2019 and 2018 to effectively manage Canada’s border and asylum system.

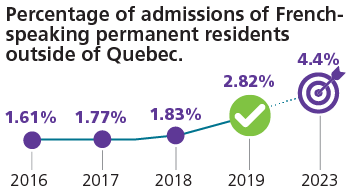

Francophone immigration outside Quebec

The Francophone Immigration Strategy, announced in March 2019, aims to achieve a target of 4.4% of French-speaking immigrants of all admissions, outside of Quebec, by 2023.

In 2019, about 8,500 French-speaking permanent residents were admitted to Canada outside of Quebec, representing 2.82% of all permanent residents admitted in Canada outside of Quebec.Footnote 31

Text version: Percentage of admissions of French-speaking permanent residents outside of Quebec

| Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of admissions for French-speaking permanent residents | 1.61% | 1.77% | 1.83% | 2.82% | 4.40% |

As of 2019, a more inclusive definition has been used to count French-speaking immigrants, resulting in a notable impact on admission data.

| Immigration Categories | Totals | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Immigrants in the economic class | 5,523 | 65% |

| Immigrants sponsored by family | 1,420 | 17% |

| Resettled refugees and protected persons in-Canada and dependants abroad | 1,445 | 17% |

| Other immigrants | 81 | 1% |

| Total | 8,469 | 100% |

Source: IRCC, Chief Data Office (CDO), Permanent Residents Data as of March 31, 2020.

Francophone settlement services

In 2019-2020, 51% of French-speaking newcomers, outside of Quebec, received at least one settlement service offered by a Francophone service provider,Footnote 32 up from 44% in 2018–2019.

The Francophone Integration Pathway consists of several innovative initiatives:

Welcoming Francophone Communities Initiative

Map of Canada

A map of Canada in which all Provinces except Quebec are shown in the same tone of the same color to illustrate their participation in the program. In addition, the map has 14 points marking the location of each participating community.

14 selected communities will receive $12.6 million (2020 to 2023) for projects to support French-speaking newcomers feel more welcome.

Language training

In 2019, IRCC’s Settlement Program launched new official language training services for French-speaking newcomers who settle in Francophone communities outside of Quebec. Seven organizations were selected to receive up to $7.6 million over 4 years. Language courses help newcomers develop language skills they need at work and in their new Francophone communities.

Canada’s next permanent resident Immigration Levels Plan

The annual Immigration Levels Plan determines how many permanent residents Canada aims to admit over the course of a calendar year. Every year, IRCC provide a projection through targets and ranges for the total number of permanent residents admitted into the country, as well as the number for each immigration category.

IRCC has presented a rolling multi-year (3 years) Immigration Levels Plan for admissions every year since 2017. The plan is developed in consultation with provinces and territories, stakeholder organizations and the public. Selection of applicants is categorized based on: economic contributions; family reunification; or support for refugees, protected persons and humanitarian and compassionate needs. The 2021-2023 Immigration Levels Plan has been developed considering the evolving situation of COVID-19 and its implications for permanent resident admissions.

2021–2023 Immigration Levels Plan

| 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Projected admissions – Targets | 401,000 | 411,000 | 421,000 | |||

| Projected admissions – Ranges | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High |

| Federal economic, provincial/ territorial nominees | 153,600 | 208,500 | 167,600 | 213,900 | 173,500 | 217,500 |

| Quebec-selected skilled workers and business | See Quebec’s immigration plan | See Quebec’s immigration plan | To be determined | To be determined | To be determined | To be determined |

| Family reunification | 76,000 | 105,000 | 74,000 | 105,000 | 74,000 | 106,000 |

| Refugees, protected persons, humanitarian and compassionate and other | 43,500 | 68,000 | 47,000 | 68,000 | 49,000 | 70,500 |

| Total | 300,000 | 410,000 | 320,000 | 420,000 | 330,000 | 430,000 |

Gender and diversity considerations in immigration

What is Gender-based Analysis Plus?

Gender-based Analysis Plus (GBA+) is an intersectional analytical process used to examine how sex and gender intersect with other identity factors (such as race, ethnicity, religion, age and mental or physical disability) that may impact the effectiveness of government initiatives. It involves examining disaggregated data and research, and considers social, economic and cultural conditions and norms. GBA+ provides federal officials with the means to achieve more equitable results for people by being more responsive to specific needs and ensuring government policies and programs are inclusive and barrier free.

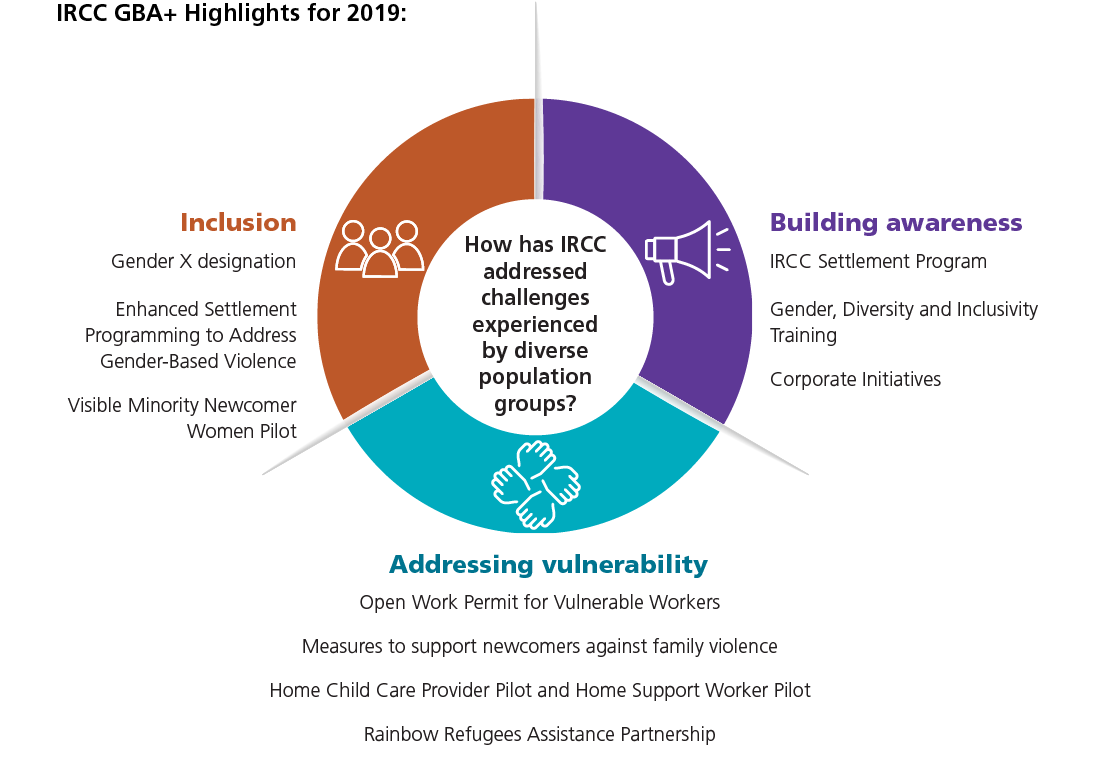

Text version: IRCC GBA+ Highlights for 2019

How has IRCC addressed challenges experienced by diverse population groups?

Inclusion

- Gender X designation

- Enhanced Settlement Programming to Address Gender-Based Violence

- Visible Minority Newcomer Women Pilot

Building Awareness

- IRCC Settlement Program

- Gender, Diversity and Inclusivity Training

- Corporate Initiatives

Addressing vulnerability

- Open Work Permit for Vulnerable Workers

- Measures to newcomers against family violence

- Home Child Care Provider Pilot and Home Support Worker Pilot

- Rainbow Refugees Assistance Partnership

Inclusion – Initiatives to address inequities and improve inclusion for diverse populations

Gender X designation

In 2019, permanent measures were put in place to ensure that individuals who do not identify exclusively as female or male can have an ’X’ for gender on their passport, travel document, citizenship certificate, or permanent resident card. This allows them to acquire documents with a gender designation that better reflects their gender identity. An ‘X’ also adheres to international standards on travel document specifications, and is the only alternative to ‘F’ and ‘M’ for the mandatory sex field in travel documents.

Enhanced Settlement Programming to Address Gender-Based Violence

IRCC funding under Canada’s Strategy to Prevent and Address Gender-Based Violence (led by Women and Gender Equality Canada) contributed to the development of a national settlement sector Gender-Based Violence Strategy Partnership. This collaboration between settlement and anti-violence sector organizations works to develop and disseminate knowledge, resources and training to strengthen the settlement sector’s capacity to address gender-based violence.

Visible Minority Newcomer Women Pilot

Recognizing the specific barriers that newcomer women of visible minorities often face (for example: gender- and race-based discrimination; precarious or low-income employment), the Department launched the Visible Minority Newcomer Women Pilot in December 2018. This pilot aims to improve economic opportunities to increase participation of newcomer women of visible minorities in the Canadian labour market. Results from the ongoing assessment of the pilot will inform employment-related services offered under the Settlement Program.

Building Awareness – Expanded programming to address equity, diversity and inclusion considerations

IRCC Settlement Program

Given the needs of newcomers with a disability, women, youth, seniors, refugees and LGBTI individuals, settlement service providers were asked to expand and customize settlement services to include mental health and well-being programming.

Gender, Diversity and Inclusivity Training

In 2019, IRCC designed and debuted two new internal courses to train employees to apply an inclusive, positive and respectful approach toward clients and colleagues, regardless of their gender identity, gender expression or sexual orientation.

Corporate Initiatives

Throughout 2019, IRCC undertook a number of internal initiatives, which included organizing numerous learning events during GBA+ Awareness Week and providing GBA+ training sessions across the Department.

Addressing Vulnerability – Programs created to improve outcomes for individuals that may experience increased vulnerabilities

Open Work Permit for Vulnerable Workers

In June 2019, IRCC introduced a new measure to enable migrant workers who have an employer-specific work permit and are in an abusive job situation to apply for an open work permit. This measure helps to ensure that migrant workers who need to leave their employer can maintain their status, and find another job.

Measures to support newcomers against family violence

In 2019, IRCC launched measures to ensure that newcomers experiencing family violence are able to apply for a fee-exempt temporary resident permit for newcomers in Canada. This gives them:

- Legal status

- Work permit

- Health-care coverage

Between the launch of the program in July 2019 and December 2019, IRCC approved approximately 25 family violence temporary residence permits.Footnote 33

Home Child Care Provider Pilot and Home Support Worker Pilot

The Home Child Care Provider and Home Support Worker pilots opened for applications on June 18, 2019, and will run for five years. They replaced the expiring Caring for Children and Caring for People with High Medical Needs pilots.

Through these pilots, caregivers benefit from a clear transition from temporary to permanent status to ensure that once caregivers have met the work experience requirement, they can become permanent residents quickly. They also benefit from occupation-specific work permits, rather than employer-specific ones, to allow for a fast change of employers when needed. The immediate family of the caregiver may also receive open work permits and study permits to help families come to Canada together.

Features of the new pilots reflect lessons learned from previous caregiver programs and test innovative approaches to addressing unique vulnerabilities and isolation associated with work in private households.

Rainbow Refugees Assistance Partnership

In June 2019, the Government of Canada announced the launch of the Rainbow Refugee Assistance Partnership. Starting in 2020, the five-year partnership will assist private sponsors with the sponsorship of 50 LGBTI refugees per year. The partnership will also strengthen collaboration between LGBTI organizations and the refugee settlement community in Canada.

How applying GBA+ helped shape changes to the Caregiver Program

Caregiver immigration has taken multiple forms in recent years, including the legacy Live-in Caregiver regulatory program, two 2014 Ministerial Instruction pilots, and several initiatives in 2019: a public policy Interim Pathway for Caregivers, and the launch of two new pilots for caregivers.

To support new policy directions, in 2014 a gender-based analysis was conducted for the Live-in Caregivers Program,Footnote 34 which found that, while a helpful route to permanent resident status for many women, the live-in requirement created vulnerabilities. Caregivers were on employer-specific work permits that linked their accommodation to their work and employer, exposing them to abuse and exploitation. They were also generally isolated from their families overseas, working for years toward permanent residence without having their immediate families with them. Due to the limited number of admissions to permanent residence in any given year, a significant backlog of applications developed, leading to prolonged periods of family separation and ongoing vulnerability for the caregivers.

In 2014, the Live-in Caregiver Program was closed to new applicants. Priority was given to processing the significant backlog of applications which stood at about 27,000 applications (or 62,000 persons). To address some of the vulnerabilities that caregivers faced, two new caregiver pilots were launched, without the mandatory live-in requirement – the Caring for Children Class and Caring for People with High Medical Needs Class. These pilots acted as transition pathways for foreign caregivers with Canadian work experience. Complementary changes were also made to the Temporary Foreign Worker Program so that in most cases, job offers made by Canadian families do not require the caregiver to live-in.

Consultations held in 2018, as part of the 2014 Caregiver Pilots review, revealed that many caregivers arrived in Canada as temporary residents without a clear pathway to permanent residence. Caregivers continued to face prolonged family separation and experienced vulnerabilities related to in-home work and having their employment status tied to a specific employer.

Responding to these findings and recognizing the significant contribution caregivers make in supporting the care needs of Canadian families, two new caregiver pilots were launched in June 2019 – the Home Child Care Provider Class, and the Home Support Worker Class. These pilots are designed to provide a clear, direct pathway to permanent residence for caregivers by assessing applicants for permanent residence and admissibility requirements before they begin work in Canada. With an occupation-specific work permit, a caregiver will be able to change jobs when necessary. The pilots also remove barriers that caregivers face in bringing their families with them to Canada, by providing open work permits for spouses/common-law partners and study permits for dependent children. IRCC will monitor the outcomes of the pilots, working to identify the impacts of these program changes on caregivers and their families, including GBA+ considerations.

GBA+ considerations for LGBTI refugee journeys

IRCC works with civil society stakeholders to support the settlement of LGBTI refugees to Canada. This work helps to support the safety of LGBTI refugees by providing policy and decision makers with a better understanding of the challenges faced by these refugees in their countries of origin and asylum, and when resettling to Canada. Barriers specific to the resettlement of LGBTI refugees have been identified and IRCC is working to address them. This includes developing enhanced knowledge of country conditions and training for IRCC staff on gender inclusion, diversity and cultural awareness.

Annex 1: Section 94 and Section 22.1 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

The following excerpt from the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), which came into force in 2002, outlines the requirements for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada to prepare an annual report to Parliament on immigration.

Reports to Parliament

94 (1) The Minister must, on or before November 1 of each year or, if a House of Parliament is not then sitting, within the next 30 days on which that House is sitting after that date, table in each House of Parliament a report on the operation of this Act in the preceding calendar year.

(2) The report shall include a description of

- (a) the instructions given under section 87.3 and other activities and initiatives taken concerning the selection of foreign nationals, including measures taken in cooperation with the provinces;

- (b) in respect of Canada, the number of foreign nationals who became permanent residents, and the number projected to become permanent residents in the following year;

- (b.1) in respect of Canada, the linguistic profile of foreign nationals who became permanent residents;

- (c) in respect of each province that has entered into a federal-provincial agreement described in subsection 9(1), the number, for each class listed in the agreement, of persons that became permanent residents and that the province projects will become permanent residents there in the following year;

- (d) the number of temporary resident permits issued under section 24, categorized according to grounds of inadmissibility, if any;

- (e) the number of persons granted permanent resident status under each of subsections 25(1), 25.1(1) and 25.2(1);

- (e.1) any instructions given under subsection 30(1.2), (1.41) or (1.43) during the year in question and the date of their publication; and

- (f) a gender-based analysis of the impact of this Act.

The following excerpt from IRPA outlines the Minister’s authority to declare when a foreign national may not become a temporary resident, which came into force in 2013, and the requirement to report on the number of such declarations.

Declaration

22.1 (1) The Minister may, on the Minister’s own initiative, declare that a foreign national, other than a foreign national referred to in section 19, may not become a temporary resident if the Minister is of the opinion that it is justified by public policy considerations.

(2) A declaration has effect for the period specified by the Minister, which is not to exceed 36 months.

(3) The Minister may, at any time, revoke a declaration or shorten its effective period.

(4) The report required under section 94 must include the number of declarations made under subsection (1) and set out the public policy considerations that led to the making of the declarations.

Annex 2: Tables

Table 1: Temporary Resident Permits and Extensions Issued in 2019 by Provision of Inadmissibility

| Description of Inadmissibility | Provision Under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act | Total Number of Permits in 2019Footnote 35 |

Females | Males |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Security (e.g., espionage, subversion, terrorism) | 34 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Human or international rights violations | 35 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Serious criminality (convicted of an offence punishable by imprisonment for at least 10 years, including offences committed outside Canada, or sentenced to more than 6 months’ imprisonment in Canada) | 36(1) | 546 | 55 | 491 |

| Criminality (convicted of an indictable offence or two summary offences from separate events, including offences committed outside Canada) | 36(2) | 3,202 | 476 | 2,726 |

| Organized criminality | 37 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Health grounds (danger to public health or public safety, excessive demand) | 38 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Financial reasons (unwilling or unable to support themselves or their dependants) | 39 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Misrepresentation | 40 | 175 | 51 | 124 |

| Cessation of refugee protection | 40.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-compliance with Act (e.g., no passport, no visa, work/study without authorization, medical check to be completed in CanadaFootnote 36) | 41 | 2,139 | 977 | 1,161 |

| Inadmissible family member | 42 | 12 | 7 | 5 |

| Total | 6,080 | 1,568 | 4,511 |

Source: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), Enterprise Data Warehouse (Master Business Reporting) as of April 27, 2020.

Table 2: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2019 by Top 10 Source Countries

| Rank | Country | Total NumberFootnote 37 | Percentage | Females | Males |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | India | 85,593 | 25 | 41,163 | 44,430 |

| 2 | China, People's Republic of | 30,246 | 9 | 16,890 | 13,356 |

| 3 | Philippines | 27,818 | 8 | 15,342 | 12,476 |

| 4 | Nigeria | 12,602 | 4 | 6,229 | 6,373 |

| 5 | Pakistan | 10,793 | 3 | 5,240 | 5,553 |

| 6 | United States of America | 10,780 | 3 | 5,562 | 5,218 |

| 7 | Syria | 10,121 | 3 | 4,881 | 5,239 |

| 8 | Eritrea | 7,030 | 2 | 3,156 | 3,874 |

| 9 | Korea, Republic of | 6,103 | 2 | 3,413 | 2,690 |

| 10 | Iran | 6,056 | 2 | 3,130 | 2,926 |

| Total Top 10 | 207,142 | 61 | 105,006 | 102,135 | |

| All Other Source Countries | 134,038 | 39 | 68,066 | 65,968 | |

| Total | 341,180 | 100 | 173,072 | 168,103 | |

Source: IRCC, Chief Data Office (CDO), Permanent Residents Data as of March 31, 2020.

Table 3: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2019 by Destination and Immigration Category

| Immigration Category | NL | PE | NS | NB | QC | ON | MB | SK | AB | BC | YT | NT | NU | Not Stated | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | |||||||||||||||

| Federal economic – SkilledFootnote 38 | 194 | 89 | 736 | 364 | 0 | 64,229 | 1,037 | 1,074 | 7,540 | 14,928 | 18 | 23 | 10 | 0 | 90,242 |

| Federal economic – CaregiverFootnote 39 | 27 | 0 | 37 | 7 | 644 | 4,942 | 46 | 110 | 1,884 | 2,090 | 6 | 13 | 1 | 0 | 9,807 |

| Federal economic – BusinessFootnote 40 | 5 | 70 | 19 | 12 | 0 | 635 | 21 | 10 | 95 | 469 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,336 |

| Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program | 398 | 344 | 1,572 | 1,827 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4,141 |

| Provincial Nominee Program | 569 | 1,727 | 3,513 | 2,849 | 0 | 12,341 | 12,545 | 10,962 | 11,236 | 12,575 | 267 | 63 | 0 | 0 | 68,647 |

| Quebec skilled workers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19,098 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 19,098 |

| Quebec business immigrants | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,387 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3,387 |

| Economic Total | 1,193 | 2,230 | 5,877 | 5,059 | 23,129 | 82,147 | 13,649 | 12,156 | 20,755 | 30,062 | 291 | 99 | 11 | 0 | 196,658 |

| Family | |||||||||||||||

| Spouses, partners and children | 196 | 122 | 742 | 374 | 7,533 | 32,533 | 2,398 | 1,649 | 10,524 | 12,565 | 79 | 74 | 20 | 0 | 68,809 |

| Parents and grandparents | 55 | 13 | 133 | 53 | 2,103 | 9,830 | 747 | 775 | 4,637 | 3,627 | 21 | 11 | 6 | 0 | 22,011 |

| Family – OtherFootnote 41 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 0 | 50 | 207 | 17 | 8 | 138 | 64 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 491 |

| Family Total | 252 | 135 | 881 | 427 | 9,686 | 42,570 | 3,162 | 2,432 | 15,299 | 16,256 | 100 | 85 | 26 | 0 | 91,311 |

| Protected Persons and Refugees | |||||||||||||||

| Protected persons in- Canada and dependants abroad | 10 | 1 | 44 | 19 | 2,434 | 13,312 | 236 | 61 | 1,296 | 1,016 | 6 | 5 | 3 | 0 | 18,443 |

| Blended visa office-referred refugees | 17 | 1 | 98 | 8 | 0 | 393 | 155 | 22 | 170 | 125 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 993 |

| Government-assisted refugees | 286 | 53 | 390 | 420 | 1,204 | 4,093 | 551 | 576 | 1,372 | 1,004 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 9,951 |

| Privately sponsored refugees | 77 | 26 | 258 | 64 | 3,610 | 7,748 | 1,104 | 558 | 4,113 | 1,564 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 13 | 19,143 |

| Protected Persons and Refugees Total | 390 | 81 | 790 | 511 | 7,248 | 25,546 | 2,046 | 1,217 | 6,951 | 3,709 | 10 | 13 | 3 | 15 | 48,530 |

| Humanitarian and Other | |||||||||||||||

| Humanitarian and otherFootnote 42 | 14 | 1 | 33 | 3 | 502 | 3,132 | 52 | 51 | 686 | 207 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4,681 |

| Humanitarian and Other Total | 14 | 1 | 33 | 3 | 502 | 3,132 | 52 | 51 | 686 | 207 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4,681 |

| Total | 1,849 | 2,447 | 7,581 | 6,000 | 40,565 | 153,395 | 18,909 | 15,856 | 43,691 | 50,234 | 401 | 197 | 40 | 15 | 341,180 |

| Percentage | 0.54% | 0.72% | 2.22% | 1.76% | 11.89% | 44.96% | 5.54% | 4.65% | 12.81% | 14.72% | 0.12% | 0.06% | 0.01% | 0.00% | 100 |

Source: IRCC, CDO, Permanent Resident Data as of March 31, 2020.

Table 4: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2019

| Immigration Category | 2019 Planned Admission Ranges | 2019 Admissions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | Female | Male | Gender X | Total | |

| Federal economic – SkilledFootnote 43 | 76,000 | 86,000 | 42,702 | 47,540 | 0 | 90,242 |

| Federal economic – CaregiverFootnote 44 | 8,000 | 15,500 | 5,747 | 4,060 | 0 | 9,807 |

| Federal economic – BusinessFootnote 45 | 500 | 1,500 | 634 | 702 | 0 | 1,336 |

| Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program | 1,000 | 5,000 | 2,019 | 2,122 | 0 | 4,141 |

| Provincial Nominee Program | 57,000 | 68,000 | 31,848 | 36,799 | 0 | 68,647 |

| Quebec skilled workers and business immigrants | 21,100 | 23,500 | 10,806 | 11,678 | 1 | 22,485 |

| Economic Total | 174,000 | 209,500 | 93,756 | 102,901 | 1 | 196,658 |

| Spouses, partners, and children | 66,000 | 76,000 | 40,433 | 28,376 | 0 | 68,809 |

| Parents and grandparents | 17,000 | 22,000 | 13,045 | 8,966 | 0 | 22,011 |

| Family – OtherFootnote 46 | - | - | 251 | 240 | 0 | 491 |

| Family Total | 83,000 | 98,000 | 53,729 | 37,582 | 0 | 91,311 |

| Protected persons in-Canada and dependants abroad | 14,000 | 20,000 | 8,936 | 9,506 | 1 | 18,443 |

| Blended visa office-referred refugees | 1,000 | 3,000 | 480 | 513 | 0 | 993 |

| Government-assisted refugees | 7,500 | 9,500 | 4,862 | 5,088 | 1 | 9,951 |

| Privately sponsored refugees | 17,000 | 21,000 | 8,746 | 10,397 | 0 | 19,143 |

| Refugees and Protected Persons Total | 39,500 | 53,500 | 23,024 | 25,504 | 2 | 48,530 |

| Humanitarian and OtherFootnote 47 | 3,500 | 5,000 | 2,563 | 2,116 | 2 | 4,681 |

| Total | 310,000 | 350,000 | 173,072 | 168,103 | 5 | 341,180 |

Source: IRCC, CDO, Permanent Resident Data as of March 31, 2020.

Table 5: Permanent Residents by Official Language Spoken, 2019

| Immigration Category | English | French | French and English | Neither | Not Stated | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic – Principal applicants | 90,478 | 2,326 | 9,910 | 571 | 39 | 103,324 |

| Female | 38,419 | 1,014 | 4,297 | 161 | 19 | 43,910 |

| Male | 52,059 | 1,312 | 5,612 | 410 | 20 | 59,413 |

| Gender X | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Economic – Partners and dependants | 68,486 | 4,992 | 4,383 | 14,393 | 1,080 | 93,334 |

| Female | 36,883 | 2,616 | 2,547 | 7,160 | 640 | 49,846 |

| Male | 31,603 | 2,376 | 1,836 | 7,233 | 440 | 43,488 |

| Total Economic | 158,964 | 7,318 | 14,292 | 14,964 | 1,119 | 196,658 |

| Female | 75,302 | 3,630 | 6,844 | 7,321 | 659 | 93,756 |

| Male | 83,662 | 3,688 | 7,448 | 7,643 | 460 | 102,901 |

| Family reunification – Principal applicants | 54,759 | 2,898 | 3,436 | 12,946 | 898 | 74,937 |

| Female | 31,849 | 1,837 | 1,859 | 7,778 | 440 | 43,763 |

| Male | 22,910 | 1,061 | 1,577 | 5,168 | 458 | 31,174 |

| Family reunification – Partners and dependants | 7,356 | 746 | 221 | 7,262 | 789 | 16,374 |

| Female | 4,353 | 411 | 130 | 4,667 | 405 | 9,966 |

| Male | 3,003 | 335 | 91 | 2,595 | 384 | 6,408 |

| Total Family Reunification | 62,115 | 3,644 | 3,657 | 20,208 | 1,687 | 91,311 |

| Female | 36,202 | 2,248 | 1,989 | 12,445 | 845 | 53,729 |

| Male | 25,913 | 1,396 | 1,668 | 7,763 | 842 | 37,582 |

| Refugees and protected persons in-Canada – Principal applicants | 14,267 | 1,477 | 1,104 | 7,880 | 524 | 25,252 |

| Female | 4,875 | 748 | 466 | 3,463 | 228 | 9,780 |

| Male | 9,390 | 729 | 638 | 4,417 | 296 | 15,470 |

| Gender X | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Refugees and protected persons in-Canada – Partners and dependants | 7,827 | 746 | 552 | 12,960 | 1,193 | 23,278 |

| Female | 4,710 | 406 | 312 | 7,185 | 631 | 13,244 |

| Male | 3,117 | 340 | 240 | 5,775 | 562 | 10,034 |

| Total Refugees and Protected Persons in-Canada | 22,092 | 2,223 | 1,656 | 20,840 | 1,717 | 48,530 |

| Female | 9,585 | 1,154 | 778 | 10,648 | 859 | 23,024 |

| Male | 12,507 | 1,069 | 878 | 10,192 | 858 | 25,504 |

| All other immigration – Principal applicants | 1,885 | 196 | 152 | 399 | 99 | 2,731 |

| Female | 986 | 105 | 64 | 241 | 59 | 1,455 |

| Male | 897 | 91 | 88 | 158 | 40 | 1,274 |

| Gender X | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| All other immigration – Partners and dependants | 1,388 | 92 | 95 | 284 | 91 | 1,950 |

| Female | 772 | 51 | 58 | 174 | 53 | 1,108 |

| Male | 616 | 41 | 37 | 110 | 38 | 842 |

| Total All Other Immigration | 3,271 | 288 | 247 | 683 | 190 | 4,681 |

| Female | 1,758 | 156 | 122 | 415 | 112 | 2,563 |

| Male | 1,513 | 132 | 125 | 268 | 78 | 2,116 |

Source: IRCC, CDO, Permanent Resident Data as of March 31, 2020.

Annex 3: Temporary migration reporting

Temporary resident permits

Under subsection 24(1) of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), an officer may issue a temporary resident permit (TRP) to a foreign national who is inadmissible or who does not otherwise meet the requirements of the Act, to allow that individual to enter or remain in Canada when it is justified under the circumstances. TRPs are issued for a limited period of time and are subject to cancellation at any time.

Table 1 in Annex 2 illustrates the number of TRPs issued in 2019, categorized according to grounds of inadmissibility under IRPA. In 2019, a total of 6,080 such permits were issued.

Public policy exemptions for a temporary purpose

In 2019, a total of 527 applications for temporary residence were granted under the public policy authority provided under subsection 25.2(1) of IRPA for certain inadmissible foreign nationals to facilitate their temporary entry into Canada as visitors, students or workers. The public policy exemption has been in place since September 2010 to advance Canada’s national interests while continuing to ensure the safety of Canadians.

Use of the negative discretion authority

In 2019, the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship did not use the negative discretion authority under subsection 22.1(1) of IRPA. This authority allows the Minister to make a declaration that, on the basis of public policy considerations, a foreign national may not become a temporary resident for a period of up to 3 years.

Annex 4: Ministerial Instructions in 2019

The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) provides the legislative authority for Canada’s immigration program and contains various provisions that allow the Minister to issue special instructions to immigration officers to enable the Government of Canada to best achieve its immigration goals. These instructions are typically issued for limited periods of time and can touch on a diverse range of issues.

As required by section 94(2) of IRPA, the following table provides a description of the instructions given by the Minister in 2019 and the date of their publication.

| Title | Description | Date of Publication | Coming into Force |

|---|---|---|---|

| Parents and Grandparents | Pursuant to section 87.3 of IRPA, Ministerial Instructions regarding the sponsorship of parents and grandparents that increased the number of applications accepted for processing from 17,000 to 20,000, and changed the intake model from randomized selection to enhanced first-in. | January 12, 2019 | January 1, 2019 |

| Caregivers | Pursuant to section 87.3 of IRPA, Ministerial Instructions regarding the 2014 caregiver pilots (Caring for Children Class, and Caring for People with High Medical Needs Class), that no new applications will be received into processing if submitted on or after June 18, 2019 (to coincide with the launch of the two new 2019 pilots (Home Support Worker Class and the Home Child Care Provider Class). | June 29, 2019 | June 18, 2019 |

| Caregivers | Pursuant to section 87.3 of IRPA, Ministerial Instructions issued to officers to not process applications for new work permits made by foreign nationals outside Canada, for work in two specified caregiving occupations, unless for work in Quebec. | June 29, 2019 | June 18, 2019 |