Statement on pre-exposure vaccination against rabies and animal bite prevention in the traveller

Published: February 10, 2026

On this page

- Preamble

- Key points for the health care provider

- Background

- Guideline development methods

- Recommendation and evidence assessment on rabies PrEP use in Canadian travellers

- Recommendations for the prevention and treatment of animal-associated injuries

- Additional considerations in post-exposure wound care

- Conclusions and research needs

- Abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- Conflicts of interest

- Appendix 1: Countries with CVV present and where RabIg is not readily available

- Appendix 2: Animal exposure prevention guidelines for travellers

- Appendix 3: Literature search sample strategy

- Appendix 4: Model inputs for estimating reductions in travel disruptions

- Appendix 5: Model inputs for estimating risk of clinical rabies among travellers

- Appendix 6. Evidence supporting SAE risk estimation

- Appendix 7: Evidence to decision framework

- Appendix 8: Assessment tables for applicability of good practice statements

- Footnotes

- References

Preamble

The Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT) provides the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) with ongoing and timely medical, scientific, and public health advice relating to tropical infectious disease and health risks associated with international travel. The Agency acknowledges that the advice and recommendations set out in this statement are based upon the best current available scientific knowledge and medical practices and is disseminating this document for information purposes to the medical community caring for travellers.

Persons administering or using drugs, vaccines, or other products should also be aware of the contents of the product monograph(s) or other similarly approved standards or instructions for use. Recommendations for use and other information set out herein may differ from that set out in the product monograph(s) or other similarly approved standards or instructions for use by the licensed manufacturer(s). Manufacturers have sought approval and provided evidence as to the safety and efficacy of their products only when used in accordance with the product monographs or other similarly approved standards or instructions for use.

Key points for the health care provider

- Rabies is a fatal viral zoonotic disease transmitted mainly through mammalian bites.

- The burden of rabies is higher in some travel destinations, often because the virus circulates among unvaccinated dogs.

- Rabies can be prevented, after exposure, by providing suitable post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP), usually rabies vaccine and rabies immunoglobulin (RabIg).

- Rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) simplifies rabies PEP by reducing the number of rabies vaccine doses required and negating the need for RabIg.

- In some situations, especially if access to PEP is uncertain, pre-travel receipt of rabies PrEP might reduce the burden of rabies PEP-related health care interactions and interventions for the exposed patient.

- Appendix 1 lists countries where CATMAT suggests offering rabies PrEP for travellers. Alternatively, rabies risk information is available on travel.gc.ca through the Public Health Agency of Canada's travel health advice. Each destination's "Health" section outlines details on rabies endemicity and access to PEP.

- In addition to rabies-specific prophylaxis, comprehensive post-exposure management should include thorough wound care and, when exposurea7.2 involves non-human primates, consideration of B virus.

Summary of recommendations

1. CATMAT suggests offering rabies PrEP to travellers visiting areas with both a relatively higher risk of rabiesfootnote a and where RabIg may not be readily availablefootnote b.

(Discretionary recommendation, very low certainty evidence)

Remarks:

- This recommendation is discretionary. To help the patient decide about vaccination, health care providers should review with them potential benefits and harms associated with rabies PrEP that are consistent with the patient's own values and preferences. The discussion should include potential alternative and/or complementary strategies to vaccination.

- When canine variant virus (CVV) is present but exposure risk is low (e.g., resort-style travel) or the duration of travel is short (e.g., one week or less), the benefits of rabies PrEP may be of less value, and patients may opt to not receive it (see Appendix 2 for information on behaviours and activities at increased risk of animal encounters).

- Vaccines given as PrEP should be administered according to the Rabies vaccines: Canadian Immunization Guide (CIG) which also provides recommendations for specific groups like laboratory personnel, veterinarians, veterinary staff, and wildlife workers.

- Thresholds for effect (e.g., the estimated absolute harms or benefits judged to be important to decision-making) are summarized in Table 1.

Rationale:

- The absolute benefit of PrEP for rabies prevention in travellers is trivial.

- Rabies PrEP may reduce the likelihood of PEP-treatment associated travel disruption by about 1% (moderate benefit; very low certainty evidence) but may increase the risk of serious vaccination-associated adverse events by 0.08% (moderate harm; very low certainty evidence). Given these estimates, CATMAT believes many patients would choose to receive rabies PrEP to avoid the risk of travel disruption.

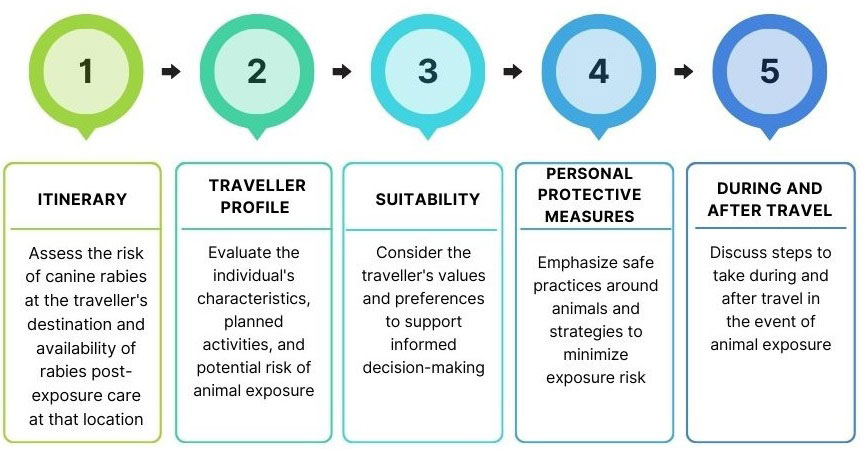

Figure 1: Text description

Itinerary: Assess the risk of canine rabies at the traveller's destination and availability of rabies post-exposure care at that location.

Traveller profile: Evaluate the individual's characteristics, planned activities, and potential risk of animal exposure.

Suitability: Consider the traveller's values and preferences to support informed decision-making.

Personal protective measures: Emphasize safe practices around animals and strategies to avoid/minimize exposure risk.

During and after travel: Discuss steps to take during and after travel in the event of animal exposure.

2. Travellers should avoid contact with animals while travelling. (Good practice statement)

Remarks:

- Refer to Appendix 2 for information on animal exposure prevention guidelines for travellers.

3. Travellers who suffer an animal injury (e.g., bite or scratch from a mammal like a dog, cat, monkey, or bat) should seek health care support as soon as possible.(Good practice statement)

Remarks:

- Immediate wound washing with water and soap for at least 15 minutes is an important measure to reduce the risk of infection after animal exposure.

- Medical assessment and PEP (if recommended) should not be delayed until return to Canada.

- Records of rabies PEP received while travelling, including the names and dates of products (RabIg and/or vaccines) administered, should be requested and kept. Consult Immunization records: Canadian Immunization Guide for a comprehensive list of important immunization details.

- Seek health care support as soon as possible after return to Canada. Bring applicable records of treatments received abroad to the health care consultation.

- Even minor appearing animal bites may have penetrated tendon sheaths, joint capsules, bone or nerve, and be at risk for serious complications.

Background

Rabies is a fatal viral disease caused by viruses of the genus Lyssavirus that can affect all mammalsReference 1. About 99% of human rabies cases are associated with dog bites and canine variant virus (CVV) in low- and middle-income rabies-endemic countriesReference 2, where 50,000-100,000 cases are estimated to occur annuallyReference 3 Reference 4. By contrast, Canada and virtually all other high-income countries have eliminated endemic cycling of CVV, resulting in human rabies being very rare in these jurisdictionsReference 5.

Immunization after exposure (i.e., PEP) to a potentially rabid animal is highly effective at preventing rabies. Rabies PrEP is also an important intervention for persons at higher risk of exposure to rabies virusReference 6. While it does not eliminate the need for rabies PEP, rabies PrEP allows for expediated PEP by reducing the number of vaccine doses and eliminating the need for RabIgReference 6

Current PEP recommendations as per the Rabies vaccines: Canadian Immunization Guide chapter are as follows:

- Persons not previously immunized against rabies

- Local treatment of wound

- Post-exposure prophylaxis with RabIgand four or five doses of rabies vaccine should begin as soon as possible.

- Persons previously appropriately immunized against rabies

- Local treatment of wound

- Post-exposure prophylaxis with two doses of rabies vaccine should begin as soon as possible.

This guidance is focused on preventing travel-associated rabies. The analysis is specifically centered on PrEP use in travellers to areas where rabies endemicity is relatively elevated, usually due to the presence of CVV.

Clinical features

The rabies virus is usually transmitted through the saliva of an infected mammal, most often via bites, but can also spread through scratches, licks, or contact with broken skin or mucous membranes that are contaminated with saliva or neural tissue/fluids from an infected mammal. Following infection, the virus replicates in muscle tissue before migrating through peripheral nerves to the brain.

The incubation period ranges from less than a week to over a year, most commonly one to three monthsReference 1. Factors thought to affect the incubation period include the amount of infectious material (e.g., saliva) introduced, the degree of innervation at the exposure site, and proximity of the exposure to the brain.

Initial clinical symptoms can include neuropathic pain at the wound site and fever, followed by progressive encephalomyelitis. Death usually occurs within 14 days of symptom onset. For a description of clinical rabies, see Rabies: For health professionals.

Risk of rabies and animal bites in travellers

On an individual basis, rabies remains exceedingly rare among travellers from high-income Western countries visiting locations with a higher disease burden. Among the 23 reported cases in this population between 2013 and 2019, no consistent pattern emerged to define a "typical" travellerReference 7; cases spanned a range of travel profiles. Most cases were acquired in Asia (13/23, 57%) or Africa (7/23, 30%). The mean age was 36 years (range: 4–65 years), and children under 16 years accounted for 13% of cases. The male-to-female ratio was 2.8:1. Migrants who have been exposed in their home countries prior to migration represented 35% of cases, while tourists and travellers visiting friends and relatives each accounted for 26% of cases. The remaining cases were reported among business travellers (9%) and expatriates (4%). Dogs were reported as the primary source of infection (74%) followed by cats (9%).

Data collected in Paris, France, between August and September 2025 highlight specific traveller behaviours disproportionately linked to animal exposuresReference 8. Of the 724 individuals who sought post-exposure care, only 69 (9.5%) had consulted a health care professional prior to travel. A majority (689/724, 95.2%) described their exposures as provoked, underscoring the importance of behavioural risk factors in animal exposures among travellers. Among the 339 travellers with reported provoked incidents, 45.7% had been petting or playing with animals, 20.6% were feeding them or attempting to help a sick animal, and 8.6% encountered animals while dining at restaurants. Another 18.9% reported incidental contact (i.e., passing close to, stepping on, or encountering animals during hiking, biking, or motorcycling). Additionally, 11.8% were exposed to monkeys during interactions involving feeding, petting, or taking pictures.

Although rabies disease is rare, the risk of animal exposure, such as dog bites, is appreciable in high burden countries. Estimates of bite incidence during travel vary, with reported rates ranging from 0.1 to 23 per 1,000 person-tripsReference 9. In high-risk destinations, travellers may face at least a 1% chance of experiencing animal exposure, equivalent to 10 bites per 1,000 person-trips. This risk is important in the context of rabies prevention and decision-making related to rabies PrEP. Specifically, the relatively common occurrence of animal exposures that could be associated with rabies transmission should also imply that seeking health care to assess the need for PEP is relatively common. Because the approach to rabies PEP changes with receipt of rabies PrEP (i.e. no RabIg and fewer rabies vaccine doses in those who received PrEP), having received PrEP may reduce travel interruption associated with receipt of rabies PEP.

Guideline development methods

Statement development process

This statement was developed by a working group (WG) under CATMAT. With support from the CATMAT Secretariat, the WG conducted a systematic literature review, synthesized the evidence, formulated key questions, drafted recommendations, and developed this statement.

Key decisions supporting the recommendation development process were discussed and approved by the full committee. The final version of the statement and its recommendations were endorsed by CATMAT.

The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodology was used to develop these recommendations. Questions were specific to Canadians travelling abroad and did not consider subjects already addressed in the rabies vaccines chapter in the CIG (e.g., PrEP schedules and routes of administration, vaccine efficacy/effectiveness/immunogenicity).

Policy and PICO questions

Policy question

Should Canadian travellers to high-burden rabies destinations, where access to RabIg may unavailable, be recommended to receive rabies PrEP?

PICO question

Population: Travellers from Canada to relatively higher-risk rabies destinations (indicated by presence of circulating rabies CVV), where access to RabIg may be unavailable.

Intervention: Rabies PrEP using either human diploid cell vaccine (HDCV) or purified chick embryo cell vaccine (PCECV).

Comparison: No rabies PrEP

Outcomes:

- prevention of clinical rabies

- avoidance of serum sickness due to RABIG

- avoidance of major travel disruptions

- serious adverse events (SAEs) associated with rabies vaccination

Literature search

In addition to the primary policy question outlined above, we also considered these contextual questions:

- What are the important risk factors for rabies exposure and animal bites among Canadian travellers (e.g., destination, duration of travel)?

- What are the values and preferences of travellers regarding the level of risk reduction that would justify the use of rabies PrEP, considering associated costs and inconvenience?

With the support of a reference librarian, a search strategy was developed based on the questions above.

We searched Embase, MEDLINE, Global Health, CAB abstracts, and Scopus (Appendix 3) for relevant literature (English or French). We also reviewed vaccine safety data from the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE). Finally, unpublished and other relevant evidence was obtained by hand-searching reference lists and consulting product monographs, government agency databases, and subject matter experts.

The outcome of serum sickness associated with RabIg was identified as important during the guideline development process, given the potential differences in SAEs between rabies vaccine alone, and the combination of rabies vaccine and RabIg. Evidence for this outcome was identified through a scoping review.

Outcomes

As part of our assessment, WG members initially rated the importance of each outcome as important or critical. These ratings were subsequently reviewed by CATMAT, with the final rating for each outcome reflecting committee consensus.

Benefits of rabies PrEP in preventing:

- Clinical rabies (critical): Diagnosis of human rabies in Canadians who have crossed an international border between the time of infection and diagnosis.

- Major travel itinerary disruptions (critical): Leaving the travel destination (due to unavailability of recommended PEP) to seek medical care in the country of exposure within 48 hours of animal exposure.

- Serum sickness (important): Immune-complex-mediated hypersensitivity reaction following the administration of RabIg.

Harms from rabies PrEP:

- SAEs following vaccination (critical): Adverse events requiring significant medical intervention, hospitalization, or resulting in permanent disability, corresponding to United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) vaccine criteria grades 3 to 5Reference 10.

We rated anxiety and fear of rabies following animal exposure as important but not critical for decision-making. Non-serious adverse events were considered minimally important to clinical decisions.

Effect thresholds

A critical component in evaluating the certainty of evidence involves defining a range of absolute effects that represent meaningful harms or benefits. In general, trivial absolute effects are not considered influential in decision-making. In contrast, absolute effects ranging from small to large may be considered meaningful and influential in decision-making. This framework enables comparisons across outcomes by distinguishing the magnitude of important effects. For example, a large critical harm is generally considered to outweigh a moderate benefit.

For the critical outcomes described under Outcomes, the committee established thresholds for benefits or harms based on what travellers would consider to be meaningful. Because studies on travellers' values and preferences were lacking, the professional experience of the WG members, who regularly support travellers in shared decision-making, was used.

| Type of effect | Outcome | Thresholds of absolute effect (benefits and harms) Number of events/100,000 person-trips |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trivial | Small | Moderate | Large | ||

| Benefits (reduction in expected events) | Rabies prevention | < 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.1 | > 0.5 |

| Major travel disruption | < 25 | 25 | 100-1000 | > 1000 | |

| Serum sickness due to RabIg | < 50 | 50 | 100 | > 1000 | |

| Harms (increase in expected events) | SAEFootnote a | < 5 | 5 | 10-100 | > 100 |

Model and key assumptions

To assess the potential benefits and harms of rabies PrEP, we employed modelling to estimate the likelihood of exposure in high-risk settings and to compare outcomes based on travellers' immunization status (i.e., whether travellers received rabies PrEP prior to travel or not).

Due to limited available information on the impact of rabies PrEP within a travel population relative to the WG's predetermined outcomes, we made informed assumptions based on the best available evidence. For example, in regions where CVV circulates, the monthly exposure risk for Canadian travellers was estimated at 1% per month travel. Because data on travel disruption from rabies-treatment seeking behaviour are scarce, we modelled the potential influence of rabies PrEP on travel continuity. This analysis assumed that all exposed travellers would seek medical attention. Major disruptions were defined as the inability to access recommended PEP (i.e., rabies vaccine alone, or rabies vaccine and RabIg) within 48 hours in the country of exposure, requiring the affected traveller to interrupt their trip in order to seek care elsewhere.

For a comprehensive overview of our model estimates and key assumptions, refer to Appendix 4.

Recommendation and evidence assessment on rabies PrEP use in Canadian travellers

Recommendation 1

1. CATMAT suggests offering rabies PrEP to travellers visiting areas with both a relatively higher risk of rabiesfootnote a and where RabIg may not be readily availablefootnote b.

(Discretionary recommendation, very low certainty evidence)

Remarks:

- This recommendation is discretionary. To help the patient decide about vaccination, health care providers should review with them potential benefits and harms associated with rabies PrEP that are consistent with the patient's own values and preferences. The discussion should include potential alternative and/or complementary strategies to vaccination.

- When CVV is present but exposure risk is low (e.g., resort-style travel) or the duration of travel is short (e.g., one week or less), the benefits of rabies PrEP may be of less value, and patients may opt to not receive it (see Appendix 2 for information on behaviours and activities at increased risk of animal encounters).

- Vaccines given as PrEP should be administered according to the rabies vaccines chapter in the CIG which also provides recommendations for specific groups like laboratory personnel, veterinarians, veterinary staff, and wildlife workers.

- Thresholds for effect (e.g., the estimated absolute harms or benefits judged to be important to decision-making) are summarized in Table 1.

Summary of the evidence

Clinical rabies

As summarized above and described in Appendix 5, risk for rabies is estimated as exceedingly low among Canadian travellers to higher rabies burden countries, e.g., < 1 reported case/100 million trips. Figure 2 (Appendix 5) presents WG modelling of the estimated risk of clinical rabies in travellers from high-income countries, highlighting that while clinical rabies is a critical outcome, the risk remains exceptionally rare. Because the absolute benefit of PrEP for rabies prevention cannot exceed the overall absolute risk of the disease, we judged this benefit to be irrelevant to decision-making as it falls below our threshold for a trivial effect of <1 reported case per 2 million.

Travel interruption

While rates of animal exposures among travellers are well documented, quantitative data on the associated time and financial costs remain limited. Key questions include whether travel is substantially disrupted to obtain rabies PEP, and whether rabies PrEP mitigates this impact. In the absence of such evidence, we developed a model estimating the likelihood of travel interruption following exposure and the potential benefit of rabies PrEP. In our framework, benefit arises when an immunized traveller can access rabies vaccine but not RabIg, as RabIg is unnecessary in those who have received PrEP. Consequently, the affected traveller avoids detouring to a location where RabIg is available. Further details are provided in Appendix 4.

Using this model, we estimated that receipt of rabies PrEP would avert 870 major travel disruptions per 100,000 person-trips (95% CI: 937 fewer to 805 fewer per 100,000 person-trips) to CVV endemic locations where rabies vaccine is reportedly available, but RabIg is not (Table 2). At the individual level, this equates to an absolute risk reduction of 0.87% (or approximately 1 disruption avoided per 115 trips). We judged this to be a moderately important benefit (Table 4).

| Risk metric | Without PrEP (per 100,000 person-trips) | With PrEP (per 100,000 person-trips) |

|---|---|---|

| Rate of animal-injuries | 1,000 | 1,000 |

| Probability that RabIg is not readily available at destination | 100% Footnote a | Not applicable Footnote b |

| Rate of travellers unable to access RabIg when needed | 1,000 Footnote a | Not applicable Footnote b |

| Probability that rabies vaccine is not readily available at destination | Not applicable Footnote c | 13% |

| Rate of travellers unable to access rabies vaccine when needed | Not applicable Footnote c | 130 |

| Estimated reduction in major travel disruptions with PrEP | Not applicableFootnote d | 870 fewer |

Serum sickness due to RabIg

We identified a retrospective observational study conducted in Bangkok, Thailand (1987-2005), where purified equine RabIg was given to 42,965 (59.56%) patients and human RabIg to 29,167 (40.44%) patients. Serum sickness was reported in 314 of the 72,132 individuals (0.44%) who received either equine RabIg (n = 312) or human RabIg (n = 2)Reference 11 Using this as the baseline likelihood for RabIg-associated serum illness, and if 1% of travellers suffer an animal exposure and receive appropriate PEP (which would not include RabIg if they have received PrEP), we estimated that PrEP would prevent 4 cases of serum sickness per 100,000 person-trips (95% CI: 11 fewer to 0.3 more per 100,000 person-trips). This was judged to be a trivial effect (Table 4).

Serious adverse events

We included thirteen studies (Appendix 6) that reported safety data associated with rabies vaccine, including SAEsReference 12 Reference 13 Reference 14 Reference 15 Reference 16 Reference 17 Reference 18 Reference 19 Reference 20 Reference 21 Reference 22 Reference 23 Reference 24. Among 2,434 vaccine recipients, we judged two SAEs to be possibly related to rabies vaccination: one case of angioedema in a child following a booster dose of HDCV, and one case involving dyspnea, angioedema, and urticaria in an adult following HDCV. Neither case was confirmed by study investigators to be causally related to the vaccine. A third SAE (i.e., esophagitis in an adult following HDCV) was reported but judged unlikely to be vaccine related.

Using these values, we estimated the likelihood of a SAE following completion of rabies vaccination as 0.082% (2 events/2,434 subjects). We then developed a risk model to assess potential vaccine-related harms in the context of travel to regions with relatively higher rabies risk (based on circulation of CVV). Specifically, we compared outcomes for travellers who received rabies PrEP versus those who did not, assuming a 1% probability of animal exposure and receipt of PEP (Table 3). For rabies PrEP, compared to no PrEP, the absolute difference in the likelihood of SAE was 82/100,000 (0.082%), or an extra SAE for every 1,220 travellers receiving rabies PrEP. We judged this to be a moderately important harm (Table 4 ).

| Immunization status | Series type | Risk (%) | Rate (per 100,000 person-trips) |

|---|---|---|---|

| With PrEP | Pre-exposure series | 0.082 | 82 |

| Post-exposure series Footnote a | 0.00082 | 0.82 | |

| Total estimated | 0.083 | 83 | |

| Without PrEP | Pre-exposure series | 0 | Not applicable |

| Post-exposure series Footnote a | 0.00086 Footnote b | 0.86 | |

| Total estimated | 0.00086 | 1 | |

Acceptability/feasibility/resources

In developing our recommendation, we assessed the acceptability and feasibility of administering rabies PrEP, compared to no PrEP, from the perspective of individual travellers, alongside relevant resource considerations (Appendix 7). We did not conduct a cost-effectiveness analysis, as such evaluations are typically applied at the societal or health system level rather than the individual level. Moreover, we found no evidence specifically describing travellers' willingness to pay out-of-pocket for rabies PrEP. However, data for other travel-related vaccines, such as those against Japanese encephalitisReference 25 or chikungunyaReference 26, indicates that travellers hold varied views on vaccines that protect against low-incidence but high-consequence diseases. Some are willing to pay for such protection, while others are not. We believe similar attitudes are likely to apply to rabies PrEP, though in these cases the perceived benefit may be more about avoiding travel disruption than preventing infection or disease.

Rabies PrEP is likely feasible for most travellers, although it may be constrained in remote communities where access to clinics offering rabies PrEP is limited. Additionally, some clinics may not offer intradermal administration due to low demand or limited provider training. In such cases, travellers may need to receive intramuscular injections, which may be more costly.

Out-of-pocket costs for rabies PrEP vary according to the clinic and vaccine schedules/regimens. In Canada, we judged the resources required to receive rabies PrEP per individual traveller to be large (more than 300$ per person per intervention). However, in the specific circumstances to which our recommendation for rabies PrEP applies, we also believe most travellers, whether or not they ultimately receive the immunization, would find it to be acceptable (Appendix 7).

Judgement

Overall, we suggest that most travellers would opt for rabies PrEP for the potential benefits it provides in relation to trip interruption, despite the increase in the likelihood of SAE compared to not receiving PrEP. This recommendation is particularly relevant in settings where rabies risk is elevated, indicated by the presence of CVV, and where RabIg may be unavailable.

| Outcome | Absolute difference (per 100,000 person-trips) |

Judgment |

|---|---|---|

| Prevention of clinical rabies (benefit) | Not applicable | Trivial |

| Avoidance of major travel disruptions (benefit) | 870 fewer | Moderate |

| Avoidance of serum sickness due to RabIg (benefit) | 4 fewer | Trivial |

| Occurrence of SAEs (harm) | 82 more | Moderate |

Based on these considerations, CATMAT makes a discretionary recommendation for rabies PrEP for travellers visiting areas where both CVV is present and timely access to indicated RabIg may be unavailable. Clinicians should assess each traveller's itinerary, access to medical care, and personal values, and engage in shared decision-making to determine whether rabies PrEP is appropriate.

Recommendations for the prevention and treatment of animal-associated injuries

Good practice recommendations were developed in accordance with the GRADE framework (see Evidence Based Process for developing travel and tropical medicine related guidelines and recommendations).

Recommendation 2

Travellers should avoid contact with animals while travelling. (good practice statement, Appendix 8)

Remarks:

- Refer to Appendix 2 for information on animal exposure prevention guidelines for travellers.

Recommendation 3

Travellers who suffer an animal injury (e.g., bite or scratch from a mammal like a dog, cat, monkey or bat) should seek health care support as soon as possible. (good practice statement, Appendix 8)

Remarks:

- Immediate wound washing with water and soap for at least 15 minutes is an important measure to reduce the risk of infection after animal exposure.

- Medical assessment and PEP (if recommended) should not be delayed until return to Canada.

- Records of rabies PEP received while travelling, including the names and dates of products (RabIg and/or vaccines) administered, should be requested and kept. Consult Immunization records: Canadian Immunization Guide for a comprehensive list of important immunization details.

- Seek health care support as soon as possible after return to Canada. Bring applicable records of treatments received abroad to the health care consultation.

- Even minor appearing animal bites may have penetrated tendon sheaths, joint capsules, bone or nerve, and be at risk for serious complications.

Additional considerations in post-exposure wound care

Principles of bite wound management

Although rabies is often the most feared consequence of mammal bites, the most common complication is soft tissue infection. To reduce this risk, prompt and thorough wound irrigation is recommended where it is not superseded by other medical management (e.g., lifesaving techniques for an injury)Reference 27. Except in specific circumstances such as envenomation where aggressive cleaning may worsen tissue damageReference 28, meticulous wound care and sterile irrigation are essential components of bite wound management. Normal saline or treated tap water is preferred for irrigation, though mild antiseptic solutions (e.g., 1% organic iodine solution) may be used, provided they do not damage exposed viable tissueReference 29. Additionally, best practices recommend removing rings, watches, or any constrictive clothing near the bite site as early as possible during initial wound careReference 30.

Despite high-quality wound care, skin and soft tissue infections following bite wounds remain common. Local complications may include abscess formation, lymphangitis, septic arthritis, tenosynovitis, and osteomyelitis. In more severe cases, bacteremia can lead to systemic complications such as sepsis, endocarditis, meningitis, or brain abscesses.

Several established risk factors increase the likelihood of infection and associated complications, including:

- bites involving a hand or joint (30-40% will become infected)Reference 31;

- cat and dog bites;

- bites with associated crush injuries;

- delayed (>12 hours) presentation for care; and

- diabetes and/or other immune-compromised statesReference 32.

Prophylactic antimicrobial therapy has been shown to reduce the risk of infection and may improve outcomes, particularly in cases involving hand bites or individuals at higher risk of complicationsReference 33 Reference 34. Since it can be difficult to accurately assess the depth and severity of a wound, travellers should be advised that even seemingly minor animal bites may have penetrated tendon sheaths, joint capsules, bones, or nerves, and can pose a risk for serious complications. Therefore, seeking professional medical evaluation as soon as possible is recommended in all cases.

When managing animal bites, it is important to consider the specific microbiological flora colonizing the mouth of the animal involved, as this can influence the choice of antimicrobial prophylaxis or treatment. While bite wounds are often polymicrobial, certain pathogens are more commonly linked to particular species. For example:

- cats and dogs: Pasteurella spp., Capnocytophaga spp.

- rats and mice: Spirillum minus, Streptobacillus moniliformis, Streptobacillus notomytis

- rabbits: Francisella tularensis

- deer, sheep, cattle, and goats: Parapoxviruses (e.g., Orf).

Although extremely rare, bite wounds may pose a risk of Clostridium tetani contamination. Travellers can reduce their risk of tetanus by following the recommendations found in the Tetanus toxoid: Canadian Immunization Guide, prior to travel.

Comprehensive treatment recommendations for bite wound infections and their complications are beyond the scope of this statement and are addressed in detail elsewhereReference 27 Reference 31.

B virus

Cercopithecine herpesvirus 1, or Macacine herpesvirus 1 is an uncommon but potentially deadly virus that is endemic in macaque monkeys, including those commonly found in zoos or research facilities worldwide, and found in the wild in many parts of Asia (with very small populations geographically limited to small areas of Florida and Texas). While macaque monkeys often carry the virus without symptoms, humans can acquire it through bites, scratches, or exposure to mucous membranes or broken skin via the monkeys' saliva, tissues, or bodily fluids. In humans, B virus infection can cause severe neurological disease, including encephalitis, and can be fatal if not treated promptly. There is no vaccine for B virus.

Travellers should protect themselves by strictly avoiding contact with all monkeys, particularly macaque monkeys, including feeding or petting them (Appendix 2). In the event of a bite, scratch, or mucosal exposure, immediate and thorough wound cleansing with soap and water is important, and urgent medical care should be sought for consideration of post-exposure prophylaxis with antiviral drugs such as valacyclovir or acyclovir. A summary of recommendations for prophylaxis and treatment of B virus infection has been described elsewhereReference 35. Individuals working with macaque monkeys (e.g. laboratory personnel, veterinarians, and field researchers) should use protective equipment (i.e., gloves, face shields, lab coats), practice strict hygiene protocols, and promptly clean and report any injuries or exposures.

Conclusion and research needs

To improve the certainty of evidence and better target recommendations for Canadian travellers, further clinical trials and observational studies of Canadian travelling populations are needed, including those which are representative of long-term travellers and individuals visiting friends and relatives. Future research on rabies and animal injury prevention among travellers should focus on expanding access to PEP in low-resource settings and improving global surveillance to identify high-risk regions and travel patterns.

CATMAT's recommendations are subject to change based on the future publication of novel data.

Abbreviations

- ACIP

- Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices

- CATMAT

- Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel

- CDC

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI

- Confidence interval

- CIG

- Canadian Immunization Guide

- CVV

- Canine-virus variant

- EtD

- Evidence to decision

- FDA

- Food and Drug Administration

- GRADE

- Grading of recommendations, assessment, development, and evaluation

- HDCV

- Human diploid cell vaccine

- N/A

- Not applicable

- NACI

- National Advisory Committee on Immunization

- PCECV

- Purified chick embryo cell vaccine

- PEP

- Post-exposure prophylaxis

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- PrEP

- Pre-exposure prophylaxis

- RCT

- Randomized control trial

- RabIg

- Rabies immunoglobulin

- SAE

- Serious adverse event

- SAGE

- Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization

- VAERS

- Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System

- WG

- Working group

- WHO

- World Health Organization

Acknowledgements

This statement was prepared by the CATMAT Animal Bites Working Group: Y Bui (lead), I Bogoch, A Khatib, C Rossi, S Schofield, J Smith, and was approved by CATMAT.

CATMAT gratefully acknowledges the contribution of: J Blackmore, L Coward, Z Davoodi, C Jensen, A Killikelly, M Laplante, E Leonard, T Nguyen, N Santesso, J Thériault, J Vachon, B Warshawsky, and the Public Health Agency of Canada Library.

CATMAT Members: M Libman (Chair), Y Bui (Vice-Chair), K Plewes (Malaria Sub-Committee Chair), I Bogoch, A Khatib, P Lagacé-Wiens, J Lee, and C Yansouni.

Former members: A Acharya and C Greenaway

Liaison representatives: J Pernica (Association of Medical Microbiology

and Infectious Disease Canada) and K O'Laughlin (US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention).

Former liaisons: K Angelo (US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) and I Viel-Thériault (Canadian Paediatric Society)

Ex-officio representatives: D Marion (D National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces), S Schofield (National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces), M Tunis and C Jensen (National Advisory Committee on Immunization [NACI] Secretariat, PHAC) and R Zimmer (Biologic and Radiopharmaceutical Drugs Directorate, Health Canada).

Former ex-officio representatives: C Rossi, E Ebert

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Appendix 1: Countries with CVV present and where RabIg is not readily available

Countries:

- Afghanistan

- Angola

- Armenia

- Azerbaijan

- Belize

- Benin

- Bolivia

- Cameroon

- Central African Republic

- Chad

- Colombia

- Democratic Republic of Congo

- Dominican Republic

- Ecuador

- El Salvador

- Equatorial Guinea

- Ethiopia

- Gabon

- Grenada

- Guatemala

- Guinea

- Guinea-Bissau

- Guyana

- Haiti

- Honduras

- Iran

- Iraq

- Kazakhstan

- Kyrgyzstan

- Laos

- Liberia

- Libya

- Mali

- Mongolia

- Myanmar

- Nicaragua

- North Korea

- Pakistan

- Republic of Congo

- Saint Kitts and Nevis

- Sierra Leone

- Somalia

- Sri Lanka

- Sudan

- Suriname

- Syria

- Tajikistan

- Turkmenistan

- Uzbekistan

- Venezuela

- Yemen

- Zambia

Appendix 2: Animal exposure prevention guidelines for travellers

To reduce the risk of injury, illness, or disease from animals while travelling, travellers should follow these precautions:

Avoid direct contact

- Do not touch, pet, or feed wild or domestic animals, even if they appear friendly or healthy.

- Keep away from sick or dead animals.

- Avoid bringing plastic bags or food when visiting areas known for animal encounters, such as monkey temples.

Follow local guidance

- Always follow instructions from guides or tour operators, especially in nature reserves, safaris, or animal sanctuaries.

- Respect barriers, signs, and designated viewing areas.

Stay alert

- Stay aware of your surroundings.

- Respect the animal's space.

- Avoid actions that may attract animals, such as carrying visible food.

Supervise vulnerable individuals

- Closely monitor children and individuals with cognitive impairments, who may not recognize risky interactions.

- Teach them to report any animal contact or bites/scratches immediately.

Plan ahead

- Before travelling, identify the nearest urban medical centres, including when visiting remote or wilderness areas.

- Be aware that long-term or frequent travel may increase the likelihood of animal exposure.

Be aware of areas/activities at increased risk of animal encounters

- Engaging in nature activities may be associated with increased likelihood of animal contact compared with resort-style travel or stays in urban centres.

- Applicable activities may include:

- Bike trips

- Camping

- Hunting

- Hiking

- Spelunking

- Visiting friends and/or relatives

- Visiting temples with monkey residents

- Walking safaris

Appendix 3: Literature search sample strategy

| Search number | Search strategy | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | ("cercopithecine herpesvirus 1" or herpes virus* B or herpes virus* simian* or "herpesvirus 1 cercopithecine" or simian herpesvirus* or " herpesvirus 1 (alpha) cercopithecine" or herpes* b or monkey b virus* or herpes* simi* or macacine herpesvirus* or rabies or dog bit* or monkey bit* or monkey scratch* or animal bit* or animal scratch*).mp. [mp=title, book title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms, population supplementary concept word, anatomy supplementary concept word] | 19,830 |

| 2 | (risk* or incidence or prevalence or morbidity or death? or die or died or dead or mortality or epidemiol* or surveill* or demograph*).mp. [mp=title, book title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms, population supplementary concept word, anatomy supplementary concept word] | 7,344,760 |

| 3 | (travel* or (visit* adj2 endemic*) or touris*).mp. [mp=title, book title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms, population supplementary concept word, anatomy supplementary concept word] | 101,240 |

| 4 | (vaccin* or immuniz* or immunis* or inoculat* or injection* or booster* or intradermal* or subcutaneous* or intramuscular* or intra dermal* or sub-cutaneous* or intra muscular*).mp. [mp=title, book title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms, population supplementary concept word, anatomy supplementary concept word] | 1,632,241 |

| 5 | (case report* or case stud*).mp. [mp=title, book title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms, population supplementary concept word, anatomy supplementary concept word] | 2,550,403 |

| 6 | (prophylaxis or therap* or treatment* or protocol* or prevent* or guideline* or guide line* or post exposure* or postexposure* or preexposure* or pre exposure* or first aid).mp. [mp=title, book title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms, population supplementary concept word, anatomy supplementary concept word] | 12,044,936 |

| 7 | "Herpesvirus 1, Cercopithecine"/ or rabies/ or Rabies virus/ | 13,111 |

| 8 | rabies/ep, mo | 3,237 |

| 9 | exp epidemiologic methods/ or exp demography/ | 7,705,469 |

| 10 | exp travel/ or travel medicine/ | 31,700 |

| 11 | exp immunization/ or exp immunization programs/ | 215,206 |

| 12 | rabies vaccines/ | 6,476 |

| 13 | case reports/ | 2,341,453 |

| 14 | exp therapeutics/ or "post-exposure prophylaxis"/ | 5,218,684 |

| 15 | (1 or 7) and (2 or 9) and (3 or 10) | 490 |

| 16 | 8 and (3 or 10) | 162 |

| 17 | 15 or 16 | 490 |

| 18 | limit 17 to yr="2000-Current" [epi] | 423 |

| 19 | (1 or 7) and (4 or 11) and (3 or 10) | 479 |

| 20 | 12 and (3 or 10) | 262 |

| 21 | 19 or 20 | 479 |

| 22 | limit 21 to yr="2000 -Current" [vaccination] | 392 |

| 23 | (5 or 13) and (1 or 7) and (3 or 10) | 78 |

| 24 | limit 23 to yr="2000-Current" [case reports] | 59 |

| 25 | ("cercopithecine herpesvirus 1" or herpes virus* B or herpes virus* simian* or "herpesvirus 1 cercopithecine" or simian herpesvirus* or " herpesvirus 1 (alpha) cercopithecine" or herpes* b or monkey b virus* or herpes* simi* or macacine herpesvirus*).mp. or "Herpesvirus 1, Cercopithecine"/ | 580 |

| 26 | (6 or 14) and 25 | 177 |

| 27 | limit 26 to yr="2000 -Current" [herpes B treatment] | 102 |

| 28 | Disability-Adjusted Life Years/ | 183 |

| 29 | (disability-adjusted life year? or dalys or daly or "years Lived With Disabilit*").mp. | 6,552 |

| 30 | 28 or 29 | 6,552 |

| 31 | (1 or 7) and 30 | 33 |

| 32 | limit 31 to yr="2000-current" [DAYLs] | 33 |

| 33 | 18 or 22 or 24 or 27 or 32 | 633 |

|

Note: An asterisk (*) acts as a truncation or wildcard symbol, representing 0, 1, or multiple characters at the end or middle of a word. It broadens search results by finding variations of a root word. |

||

Appendix 4: Model Inputs for estimating reductions in travel disruptions

To assess the benefits and risks of rabies PrEP, we used modelling to estimate exposure likelihood in a high-risk setting, associated health outcomes, and the potential impact of pre-immunizing travellers.

The following key assumptions and data inputs were used in our modelling:

- If RabIg was reported as available in a location, we presumed rabies vaccine was also available.

- We assumed individuals who experienced an animal bite or scratch would seek immediate medical advice and receive rabies PEP in accordance with the Canadian Immunization Guide.

- In high-risk settings where CVV is present (e.g., Asia or Africa), we estimated the probability of sustaining an injury requiring PEP at 1% per month of travel (10 exposures per 1,000 person- trips).

Due to a lack of published studies quantifying time lost from travel as a result of seeking post-exposure rabies care, we used modelling to estimate the impact of PrEP on major travel disruptions. The following assumptions and data inputs were applied:

- We limited the analysis to countries where CVV is known to circulate, as these account for the majority of global human rabies cases and represent higher-risk destinations for travellers.

- We used the availability of PEP at travel destinations, as reported in the United States' Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) database (accessed June 2025) as a proxy to estimate the potential for travel disruption. Among countries where CVV is present, RabIg was reported as unavailable in 46% (53/115), while rabies vaccine was unavailable in 13% (15/115).

- We defined major travel disruption as the inability to access standard-of-care PEP within 48 hours of animal exposure as set out in the CDC database.

- If RabIg was indicated and not readily available within 48 hours at the travel destination, we assumed that travellers would need to seek care elsewhere, thereby disrupting their travel itinerary.

- Travel disruptions were assumed to be more significant for full rabies PEP schedules (RabIg + 4 or 5 doses of vaccine) compared to partial rabies PEP schedules for travellers who had received rabies PrEP (2 doses of vaccine).

Appendix 5: Model inputs for estimating risk of clinical rabies among travellers

| Jurisdiction | Cases | Region of acquisition (number of cases) | Estimated travel volume (millions) |

Overall attack rate |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Americas | Africa | Asia | ||||

| Canada | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 224 | 0/224 |

| United States | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 551 | 2/551 |

| Europe | 7 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1200 | 7/1200 |

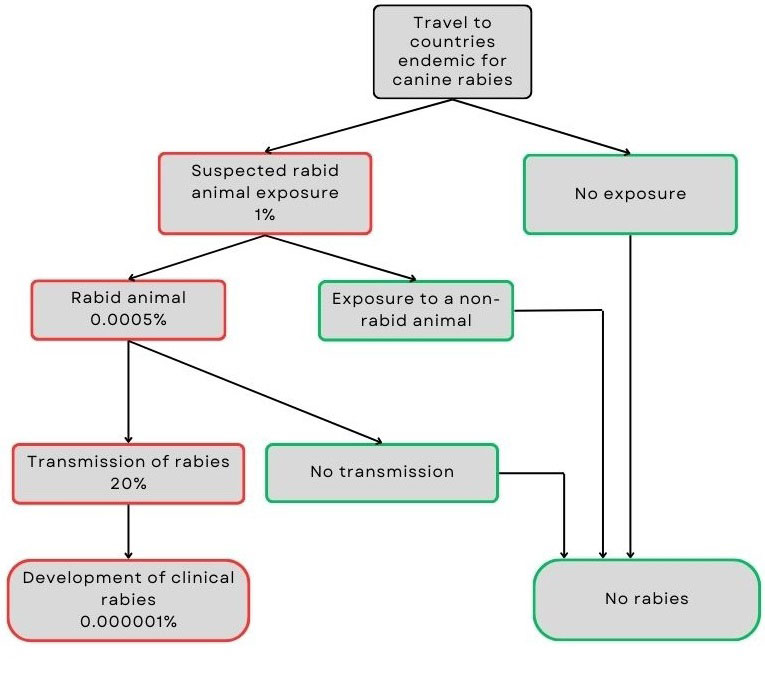

Figure 2: Text description

Travellers to countries where canine rabies is endemic face an estimated 1% risk of exposure to a suspected rabid animal.

- No exposure means no risk of developing rabies.

- If exposure occurs, there's a 0.0005% chance the animal is actually rabid.

- If the animal is not rabid, there is no risk.

- If the animal is rabid, there's a 20% chance the virus will be transmitted.

- If transmission does not occur, there is no risk.

- If transmission does occur, the traveller may develop clinical rabies.

Combining these probabilities, the estimated risk of developing clinical rabies for travellers to endemic regions is approximately 0.000001%.

| Input data | Values | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Average rabies incidence per year among travellers | 2.6 [range 1.9 to 3.7] | Carrara, 2013Reference 36 |

| Probability that an animal exposure involves a rabid mammal | 0.0005% | Estimate Footnote a |

| Probability of rabies virus transmission | 20% [range 0.1% to 60%] | Medley, 2017Reference 37 Cleaveland, 2022Reference 38 Hampson, 2015Reference 39 |

Appendix 6. Evidence supporting SAE risk estimation

| Study | Vaccine | Population | Number | Reported SAEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anderson, 1980 | HDCV | Adults and children | 90 | 0 |

| Ajjan, 1989 | HDCV | Adults (veterinary students) | 73 | 0 |

| Arora, 2004 | HDCV | Adults | 45 | 0 |

| Briggs, 2000 | PCECV | Patients with animal exposures | 136 | 0 |

| Endy, 2019 | PCECV | Adults | 59 | 0 |

| Guiambao, 2005 | PCECV | Patients with animal exposures | 113 | 0 |

| Guiambao, 2019 | PCECV | Adults and children | 420 | 0 |

| Guiambao, 2022 | HDCV | Adults and children | 307 | 0 |

| Mills, 2011 | HDCV | Adults (travellers) | 420 | 0 |

| Recuenco, 2017 | PCECV | Adults (lab workers, epidemiologists, and first responders) | 130 | 0 |

| Sabchareon, 1999 | HDCV | Children | 199 | 1Footnote a |

| Soentjens, 2019 | HDCV | Adults (armed forces) | 500 | 1Footnote b |

| Suntharasamai, 1994 | PCECV | Adults (veterinary students) | 133 | 0 |

Appendix 7: Evidence to decision framework

Question: Should Canadian travellers to high-burden rabies destinations, where access to RabIg may unavailable, be recommended to receive rabies PrEP?

Population: Travellers from Canada to relatively higher-risk rabies destinations (indicated by presence of circulating rabies CVV), where access to RabIg may not be available.

Intervention: Rabies PrEP using HDCV or PCECV

Comparison: No rabies PrEP

Main outcomes: Clinical rabies, major travel disruptions, serum sickness, and SAEs

Setting: International travel

Perspective: Individual

Background: Rabies is an acute, progressive encephalomyelitis that is almost invariably fatal once clinical symptoms appear. CATMAT reviewed the available evidence and applied GRADE to inform its recommendations regarding rabies PrEP for travellers to rabies-endemic areas.

Conflict of interests: None

Assessment

| Domain | Judgement | Research evidence and additional considerations |

|---|---|---|

Problem: Is the problem a priority? |

No |

Rabies is a universally fatal disease. |

Desirable effects: How substantial are the desirable anticipated effects? |

Trivial |

Systematic reviews addressing our key outcomes and supporting research questions, as outlined in the Guideline Development Methods, were conducted using searches completed up to January 10, 2024. The evidence for the outcome of serum sickness was identified through a scoping review. Estimates were used to model effects on critical outcomes. Estimates represent effects in high-risk areas (i.e., where CVV is present) and where access to indicated RabIg is not readily available. See estimates of desirable effects in Table 10. Major travel disruptions: The number of major travel disruptions avoided with PrEP is 870 fewer per 100,000 person-trips, considered to be moderate. Clinical rabies: The risk of clinical rabies to Canadian travellers is extremely low. The benefit of rabies PrEP would be trivial. Serum sickness: The number of serum sickness avoided with PrEP is estimated to be 4 fewer per 100,000 person-trips, considered to be trivial. Additional considerations: The certainty of evidence was downgraded by two levels for risk of bias. |

Undesirable effects: How substantial are the undesirable anticipated effects? |

Trivial |

See estimates of undesirable effects in Table 10. Additional considerations: The certainty of evidence was downgraded by two levels for risk of bias. |

Certainty of evidence: What is the overall certainty of the evidence of effects? |

Very low |

The overall certainty of evidence for critical outcomes is very low. |

Importance of outcomes to/in/for/in relation to affected population: Is there important uncertainty about or variability in how much travellers value the main outcomes? |

Important uncertainty or variability |

The WG identified the following outcomes as critical or important to decision-making: Desirable outcomes:

Undesirable outcomes:

Although we did not identify specific evidence, the WG believes that travellers would probably believe these outcomes were critical or important. Additional considerations: Clinicians should allow for discussion of this variability as part of the joint decision-making process. |

Balance of effects: Does the balance between desirable and undesirable effects favour the intervention or the comparison? |

Favours the comparison |

Estimates for benefit and harm were both small. However, we believe most travellers would place more value on avoiding travel disruption than on SAEs. Therefore, PrEP was favoured in high-risk settings where RabIg was likely not readily available. |

Resource considerations: How large are the resource requirements (costs) to the individual? |

Large costs |

Out-of-pocket costs vary according to the clinic, and vaccine schedules and regimens. In Canada, we judged the resources required to receive rabies PrEP per individual traveller to be large (more than 300$ per person per interv ention). |

Equity: |

Reduced |

As the perspective was the individual traveller, equity considerations were not explicitly included in our assessment. |

Acceptability: |

No |

We judged the intervention to be probably acceptable to most. Additional considerations: Certain factors may reduce acceptability, including fear of needles or vaccines, and the logistical burden of completing a multi-dose series (particularly the 3-dose schedule), which requires clinic visits 3 to 4 weeks before departure. |

Feasibility: |

No |

We judged the intervention to be probably feasible to most. Additional considerations: Feasibility may be constrained in remote communities where access to clinics offering rabies PrEP is limited. Some clinics may not offer intradermal administration due to low demand or limited provider training. |

Type of recommendation

Discretionary recommendation for the intervention (rabies PrEP compared to no PrEP).

Conclusions

Recommendation

1. CATMAT suggests offering rabies PrEP to travellers visiting areas with both a relatively higher risk of rabiesfootnote a and where RabIg may not be readily availablefootnote b.

(Discretionary recommendation, very low certainty evidence)

Remarks:

- This recommendation is discretionary. To help the patient decide about vaccination, health care providers should review with them potential benefits and harms associated with rabies PrEP that are consistent with the patient's own values and preferences. The discussion should include potential alternative and/or complementary strategies to vaccination.

- When CVV is present but exposure risk is low (e.g., resort-style travel) or the duration of travel is short (e.g., one week or less), the benefits of rabies PrEP may be of less value, and patients may opt to not receive it (see Appendix 2 for information on behaviours and activities at increased risk of animal encounters).

- Vaccines given as PrEP should be administered according to the rabies vaccines chapter in the CIG which also provides recommendations for specific groups like laboratory personnel, veterinarians, veterinary staff, and wildlife workers.

- Thresholds for effect (e.g., the estimated absolute harms or benefits judged to be important to decision-making) are summarized in Table 1.

Rationale:

- The absolute benefit of PrEP for rabies prevention in travellers is trivial.

- Rabies PrEP may reduce the likelihood of PEP-treatment associated travel disruption by about 1% (moderate benefit; very low certainty evidence) but may increase the risk of serious vaccination-associated adverse events by 0.08% (moderate harm; very low certainty evidence). Given these estimates, CATMAT believes many patients would choose to receive rabies PrEP to avoid the risk of travel disruption.

| Outcomes | Number of participant (studies) contributing to effect estimate | Additional participants (studies) considered in GRADE assessment | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk difference with PrEP | Risk without PrEP | |||||

| Clinical rabies | Not applicable (modelling) |

Not applicable | Not applicable | Not estimable | No studies have been identified that measured incidence of clinical rabies when comparing PrEP to no PrEP. Given that the estimated risk of rabies among travellers is extremely low, approximately 1 in 100 million, the difference in clinical rabies with PrEP among travellers would be extremely small. | |

| Major travel disruption | Not applicableFootnote a (modelling) | Not applicable | Very lowFootnote b Footnote c | Not estimable | 870 fewer per 100,000 trips (937 fewer to 805 fewer) | 1% |

| Serum sickness due to RabIg | 72,132 (1 non-randomized study) |

Not applicable | Very lowFootnote b | Not estimable | 4 fewer per 100,000 trips (11 fewer to 0.3 more) | 0.4% |

| SAE | 2,434 (13 non-randomised studies) |

(3 non-randomised studies)Footnote d | Very lowFootnote b Footnote e | Not estimable | 82 more per 100,000 trips (65 more to 101 more) | 0. 00086% |

Appendix 8: Assessment tables for applicability of good practice statements

Good practice statement: Travellers should avoid contact with animals while travelling.

| Criteria | Supporting information | Verification |

|---|---|---|

| Population and intervention components are clear | Not applicable. | Yes |

| Message is really necessary in regard to actual health care practice | Practicing safe animal interactions and avoiding contact are important strategies to prevent exposure to animals that may carry infectious diseases. However, adherence to these recommendations is often suboptimal. | Yes |

| Implementing the GPS results in a large net positive consequence | Yes, reducing exposure to animals helps lower the risk of injury and transmission of the pathogens they may carry. | Yes |

| Collecting and summarizing the evidence is a poor use of a guideline panel's limited time, energy or resources. The opportunity cost of collecting and summarizing the evidence is large and can be avoided. | Yes, this recommendation is about advising travellers to protect themselves. The advice is based on well-established principles of public health and risk mitigation, and the time and resources required to collect and summarize additional evidence would detract from addressing other priorities. | Yes |

| There is a well-documented clear and explicit rationale connecting the indirect evidence | Yes, reducing exposure to animals is reasonably expected to reduce the likelihood of injury and infection. | Yes |

| Clear and actionable | Not applicable. | Yes |

Final judgement: development of GPS is appropriate.

Good practice statement: Travellers who suffer an animal injury (e.g., bite or scratch from a mammal like a dog, cat, monkey or bat) should seek health care support as soon as possible.

| Criteria | Supporting information | Verification |

|---|---|---|

| Population and intervention components are clear | Not applicable. | Yes |

| Message is really necessary in regard to actual health care practice | Delays in seeking medical care after an animal-related injury can lead to serious illness or death. | Yes |

| Implementing the GPS results in a large net positive consequence | Yes, educating travellers on the appropriate steps to take following animal exposure can reduce the risk of adverse health outcomes. | Yes |

| Collecting and summarizing the evidence is a poor use of a guideline panel's limited time, energy or resources. The opportunity cost of collecting and summarizing the evidence is large and can be avoided. | Yes, this recommendation is about advising travellers to seek health care. The advice is based on well-established principles of public health and risk mitigation, and the time and resources required to collect and summarize additional evidence would detract from addressing other priorities. | Yes |

| There is a well-documented clear and explicit rationale connecting the indirect evidence | Yes, recommending that injured travellers seek medical care is a reasonable and well-established approach to preventing or reducing injury, infection, and death. | Yes |

| Clear and actionable | Not applicable. | Yes |

Final judgement: development of GPS is appropriate.

Footnotes

- Footnote 1

-

Indicated by presence of circulating rabies canine variant virus.

- Footnote b

-

Indicated as not readily available within 48 hours of patient presenting for care in most of the country.

References

- Reference 1

-

Rupprecht CE, Ertl HCJ. Lyssaviruses and Rabies Vaccines. In: Plotkin S OW, Offit P, editors. Plotkin's Vaccines. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2023. p. 969-97.e13.

- Reference 2

-

World Health Organization. Rabies vaccines: WHO position paper, April 2018 - Recommendations. Vaccine. 2018;36(37):5500-3.

- Reference 3

-

Carvalho MS, Hampson K, Coudeville L, Lembo T, Sambo M, Kieffer A, et al. Estimating the Global Burden of Endemic Canine Rabies. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2015;9(4).

- Reference 4

-

Gan H, Hou X, Wang Y, Xu G, Huang Z, Zhang T, et al. Global burden of rabies in 204 countries and territories, from 1990 to 2019: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2023;126:136-44.

- Reference 5

-

Rabies: Monitoring [Internet]. Ottawa: Government of Canada; [updated 2024 Oct 3]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/rabies/surveillance.html.

- Reference 6

-

Rabies vaccines: Canadian Immunization Guide [Internet]. Ottawa: Government of Canada; [updated 2025 Jun 13]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-4-active-vaccines/page-18-rabies-vaccine.html.

- Reference 7

-

Gautret P, Diaz-Menendez M, Goorhuis A, Wallace RM, Msimang V, Blanton J, et al. Epidemiology of rabies cases among international travellers, 2013–2019: A retrospective analysis of published reports. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2020;36.

- Reference 8

-

Itani O. Preventing rabies in travelers [Personal communication]. 2025 Oct 1.

- Reference 9

-

Gautret P, Parola P. Rabies vaccination for international travelers. Vaccine. 2012;30(2):126-33.

- Reference 10

-

Food and Drug Administration. Guidance for Industry: Toxicity Grading Scale for Healthy Adult and Adolescent Volunteers Enrolled in Preventive Vaccine Clinical Trials [Internet]. Federal Register; [updated 2007 Sep 27}. Available from: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2007/09/27/E7-19155/guidance-for-industry-toxicity-grading-scale-for-healthy-adult-and-adolescent-volunteers-enrolled-in.

- Reference 11

-

Suwansrinon K, Jaijareonsup W, Wilde H, Benjavongkulchai M, Sriaroon C, Sitprija V. Sex- and age-related differences in rabies immunoglobulin hypersensitivity. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2007;101(2):206-8.

- Reference 12

-

Rapheal E, Stoddard ST, Anderson KB. Surveying Health-Related Knowledge, Attitudes, and Behaviors of U.S.-Based Residents Traveling Internationally to Visit Friends and Relatives. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 2020;103(6):2591-9.

- Reference 13

-

Ajjan N, Pilet C. Comparative study of the safety and protective value, in pre-exposure use, of rabies vaccine cultivated on human diploid cells (HDCV) and of the new vaccine grown on Vero cells. Vaccine. 1989;7(2):125-8.

- Reference 14

-

Arora A, Moeller L, Froeschle J. Safety and Immunogenicity of a New Chromatographically Purified Rabies. Journal of Travel Medicine. 2006;11(4):195-200.

- Reference 15

-

Briggs D. Purified Chick Embryo Cell Culture Rabies Vaccine: interchangeability with Human Diploid Cell Culture Rabies Vaccine and comparison of one versus two-dose post-exposure booster regimen for previously immunized persons. Vaccine. 2000;19(9-10):1055-60.

- Reference 16

-

Endy TP, Keiser PB, Wang D, Jarman RG, Cibula D, Fang H, et al. Serologic Response of 2 Versus 3 Doses and Intradermal Versus Intramuscular Administration of a Licensed Rabies Vaccine for Preexposure Prophylaxis. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2020;221(9):1494-8.

- Reference 17

-

Quiambao BP, Dimaano EM, Ambas C, Davis R, Banzhoff A, Malerczyk C. Reducing the cost of post-exposure rabies prophylaxis: efficacy of 0.1ml PCEC rabies vaccine administered intradermally using the Thai Red Cross post-exposure regimen in patients severely exposed to laboratory-confirmed rabid animals. Vaccine. 2005;23(14):1709-14.

- Reference 18

-

Quiambao BP, Ambas C, Diego S, Bosch Castells V, Korejwo J, Petit C, et al. Intradermal post-exposure rabies vaccination with purified Vero cell rabies vaccine: Comparison of a one-week, 4-site regimen versus updated Thai Red Cross regimen in a randomized non-inferiority trial in the Philippines. Vaccine. 2019;37(16):2268-77.

- Reference 19

-

Quiambao BP, Lim JG, Bosch Castells V, Augard C, Petit C, Bravo C, et al. One-week intramuscular or intradermal pre-exposure prophylaxis with human diploid cell vaccine or Vero cell rabies vaccine, followed by simulated post-exposure prophylaxis at one year: A phase III, open-label, randomized, controlled trial to assess immunogenicity and safety. Vaccine. 2022;40(36):5347-55.

- Reference 20

-

Mills DJ, Lau CL, Fearnley EJ, Weinstein P. The Immunogenicity of a Modified Intradermal Pre‐exposure Rabies Vaccination Schedule—A Case Series of 420 Travelers. Journal of Travel Medicine. 2011;18(5):327-32.

- Reference 21

-

Recuenco S, Warnock E, Osinubi MOV, Rupprecht CE. A single center, open label study of intradermal administration of an inactivated purified chick embryo cell culture rabies virus vaccine in adults. Vaccine. 2017;35(34):4315-20.

- Reference 22

-

Sabchareon A, Lang J, Attanath P, Sirivichayakul C, Pengsaa K, Mener Valentine L, et al. A New Vero Cell Rabies Vaccine: Results of a Comparative Trial with Human Diploid Cell Rabies Vaccine in Children. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1999;29(1):141-9.

- Reference 23

-

Soentjens P, Andries P, Aerssens A, Tsoumanis A, Ravinetto R, Heuninckx W, et al. Preexposure Intradermal Rabies Vaccination: A Noninferiority Trial in Healthy Adults on Shortening the Vaccination Schedule From 28 to 7 Days. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2019;68(4):607-14.

- Reference 24

-

Suntharasamai P, Chaiprasithikul P, Wasi C, Supanaranond W, Auewarakul P, Chanthavanich P, et al. A simplified and economical intradermal regimen of purified chick embryo cell rabies vaccine for postexposure prophylaxis. Vaccine. 1994;12(6):508-12.

- Reference 25

-

Hills SL, Fischer M, Biggerstaff BJ. Perceptions among the U.S. population of value of Japanese encephalitis (JE) vaccination for travel to JE-endemic countries. Vaccine. 2020;38(9):2117-21.

- Reference 26

-

Lindsey N. Value of a vaccine to prevent travel-related chikungunya for US persons [Internet]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2023 Jun 22. [Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/acip/downloads/slides-2023-06-21-23/02-Chikungunya-Lindsey-508.pdf].

- Reference 27

-

Stefanopoulos P, Karabouta Z, Bisbinas I, Georgiannos D, Karabouta I. Animal and human bites: evaluation and management. Acta Orthopaedica Belgica. 2004;70(1):1-10.

- Reference 28

-

Guidelines for the Management of Snakebites. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. [cited 2025 Oct 6]. Available from: https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=5916245.

- Reference 29

-

Rothe K, Tsokos M, Handrick W. Animal and Human Bite Wounds. Deutsches Ärzteblatt international. 2015;115(25):433-43.

- Reference 30

-

Gold BS, Dart RC, Barish RA. Bites of Venomous Snakes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2002;347(5):347-56.

- Reference 31

-

Brook I. Management of Human and Animal Bite Wounds. Advances in Skin & Wound Care. 2005;18(4):197-203.

- Reference 32

-

Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, Everett ED, Dellinger P, Goldstein EJC, et al. Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Skin and Soft-Tissue Infections. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2005;41(10):1373-406.

- Reference 33

-

Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, Dellinger EP, Goldstein EJC, Gorbach SL, et al. Practice Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Skin and Soft Tissue Infections: 2014 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2014;59(2):e10-e52.

- Reference 34

-

Medeiros IM, Saconato H. Antibiotic prophylaxis for mammalian bites. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2001(2).

- Reference 35

-

Cohen Jeffrey I, Davenport David S, Stewart John A, Deitchman S, Hilliard Julia K, Chapman Louisa E. Recommendations for Prevention of and Therapy for Exposure to B Virus (Cercopithecine Herpesvirus1). Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2002;35(10):1191-203.

- Reference 36

-

Carrara P, Parola P, Brouqui P, Gautret P. Imported human rabies cases worldwide, 1990-2012. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2013;7(5):e2209.

- Reference 37

-

Medley AM, Millien MF, Blanton JD, Ma X, Augustin P, Crowdis K, et al. Retrospective Cohort Study to Assess the Risk of Rabies in Biting Dogs, 2013(-)2015, Republic of Haiti. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2017;2(2).

- Reference 38

-

Cleaveland S, Fevre EM, Kaare M, Coleman PG. Estimating human rabies mortality in the United Republic of Tanzania from dog bite injuries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2002;80(4):304-10.

- Reference 39

-

Hampson K, Coudeville L, Lembo T, Sambo M, Kieffer A, Attlan M, et al. Estimating the global burden of endemic canine rabies. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2015;9(4):e0003709.

- Reference 40

-

Dobardzic A, Izurieta H, Woo EJ, Iskander J, Shadomy S, Rupprecht C, et al. Safety review of the purified chick embryo cell rabies vaccine: Data from the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), 1997–2005. Vaccine. 2007;25(21):4244-51.

- Reference 41

-

Moro PL, Lewis P, Cano M. Adverse events following purified chick embryo cell rabies vaccine in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) in the United States, 2006–2016. Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2019;29:80-1.

- Reference 42

-

Williams M, Moro PL, Woo EJ, Paul W, Lewis P, Petersen BW, et al. Post-Marketing Surveillance of Human Rabies Diploid Cell Vaccine (Imovax) in the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) in the United States, 1990‒2015. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 2016;10(7).