Archived: Considerations for the use of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir to treat COVID-19 in the context of limited supply [2022-02-24]

Date published: February 24, 2022

On this page

Executive summary

On January 17, 2022, Health Canada authorized nirmatrelvir/ritonavir (PAXLOVID™), Canada’s first oral antiviral treatment for mild to moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in adults with positive results of direct severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viral testing, who are at high risk for progression to severe COVID-19, including hospitalization or death. The product monograph provides information to support the safe and effective use of the drug.

The Government of Canada has procured an initial quantity of 1 million treatment courses. Delivery of a limited quantity starts the week of January 17, 2022. Subsequent larger quantities will be delivered throughout the year. However, during the period when nirmatrelvir/ritonavir is in short supply compared to potential demand, prioritizing access to treatment is necessary.

The following interim recommendations aim to assist provinces and territories in their planning for the deployment of the initial supply of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir based on clinical risk factors, and health equity considerations.

- Prioritize individuals who are at the highest risk for severe illness and hospitalization. Age is the strongest risk factor for severe illness and hospitalization. Within older age groups, those who are unvaccinated or whose vaccinations are not up to date are at the highest risk.

- Consider making a greater supply available for use in rural and remote communities where there is limited access to tertiary care, and in situations where social and economic determinants of health, such as food insecurity, inadequate housing and a higher level of pre-existing medical conditions may exacerbate health inequalities.

- Infection must be confirmed and treatment initiated within 5 days of symptom onset. If reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing is not possible, or if results would not be available until more than 5 days from symptom onset, rapid antigen detection tests (RADT) may be used. A thorough medication history should be taken before treatment is initiated due to the potential for serious drug interactions.

Individuals in the following categories have the highest likelihood of severe illness and should be given priority for treatment given limited supply.

- Moderately to severely immunocompromised individuals not expected to mount an adequate response to SARS-CoV-2 infection, regardless of vaccinationFootnote 1 status.

- Individuals ≥80 years of age whose vaccinations are not up to date.

- Individuals ≥60 years of age residing in underserved, rural or remote communities, residing in a long-term care setting, or living in, or from First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities whose vaccinations are not up to date.

Footnotes

- Footnote 1

-

Refers to COVID-19 vaccines

Note: These recommendations do not supersede overarching legislative, regulatory, policy and practice requirements, including those governing health professionals.

Foreword

Vaccination and non-pharmaceutical public health measures remain the most important tools to prevent serious illness from SARS-CoV-2 infection. Both the Public Health Agency of Canada and Health Canada strongly recommend vaccination for all eligible people living in Canada. This includes people who are pregnant, may become pregnant or are breast-feeding.

Therapeutic treatment is an important and critical complement to vaccines. On January 17, 2022, Health Canada authorized the first oral antiviral treatment for COVID-19. The therapy consists of 2 co-packaged oral medications: nirmatrelvir and ritonavir (PAXLOVID™). It is to be used to treat adults with mild to moderate COVID-19 who are at high risk for progression to severe COVID-19, including hospitalization or death. The product monograph provides information to support the safe and effective use of the drug.

The Government of Canada signed an agreement with Pfizer Inc. to procure an initial quantity of 1 million treatment courses of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir, subject to Health Canada’s authorization. Delivery of a limited quantity starts the week of January 17, 2022. Subsequent larger quantities will be delivered throughout the year. However, when nirmatrelvir/ritonavir is in short supply compared to potential demand, prioritizing access to treatment will be necessary.

1 Purpose

The purpose of this document is to support provinces and territories in their planning for the deployment of the initial supply of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir. The ultimate goal is to ensure that across Canada, those with the greatest need (and most likely to benefit) have equitable access to what will be, initially, a limited supply.

These interim considerations will be supplemented by clinical and implementation recommendations that are being developed by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health and l’Institut national d'excellence en santé et services sociaux.

This document recognizes the importance of jurisdictional, ethical, technical, and procedural considerations, and the evolving epidemiologic knowledge of current risk factors for severe disease. They are not intended to replace the clinical judgment of a health care provider.

The measures are based on available information and expert opinion. The aim is to identify:

- patient populations who are likely to derive the most benefit from access to nirmatrelvir/ritonavir for the treatment of COVID-19; and

- special considerations that could impact the prioritizing of individuals to receive scarce supply

Provinces and territories adopting or adapting this guide (or elements thereof) are encouraged to develop implementation plans, including the use of and access to COVID-19 testing.

2 Guiding principles

The ethical and clinical considerations are not the same for all medical countermeasures (therapeutics, vaccines, diagnostics and personal protective equipment). The National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) provides advice to the Public Health Agency of Canada on the use of vaccines, including COVID-19 vaccines. Where appropriate and applicable, this interim guide draws on the National Advisory Committee on Immunization’s recommendations for prioritizing vaccines for key populations when vaccine supply was limited. It is also consistent with:

- the Public health ethics framework: A guide for use in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada; and

- existing federal policies and frameworks, including those governing science- and risk-based decision making

The recommendations stem from 2 public health ethical obligations:

- the duty to reduce the impact of social inequities on COVID-19 outcomes in disadvantaged communities; and

- the duty to manage scarce resources to promote public health

The orientation of these recommendations consider the following public health ethical dimensions in the context of maximizing benefits produced by a scarce resource. Consideration of these broader, public health principles complement clinical ethics, which focus on the well-being of individual patients who may meet the clinical eligibility criteria of the product monograph.

Respect for persons, communities and human rights

Respect for persons and communities means recognizing the inherent human rights, dignity, and unconditional worth of all persons, regardless of their human condition (for example, age, gender, race, ethnicity, disability, socioeconomic status, social worth, pre-existing health conditions, and need for support). This entails recognizing the unique capacity of individuals and communities to make decisions about their own aims and actions, and respecting the rights and freedoms that form the foundation of our society.

In the context of the response to COVID-19, respecting autonomy may entail:

- recognizing the importance of public consultation and explanation of the basis for decisions

- providing information in a manner that is truthful, honest, timely and accessible; and

- providing individuals with the needed personal supports and the opportunity to exercise as much choice as possible when this is consistent with the common good

Respect for communities requires considering the potential impact of decisions on all communities and groups that may be affected, and respecting the specific rights of, and responsibilities towards, Indigenous Peoples.

Justice

Justice entails treating all persons and groups fairly and equitably, with equal concern and respect, in light of what is owed to them as members of society. This does not mean treating everyone the same. It does mean avoiding discrimination, and minimizing or eliminating inequities in the distribution of burdens, benefits, and opportunities to preserve health and well-being.

In the context of COVID-19, it also means carefully considering the impact of decisions and their implementation on those who have the greatest needs, are especially vulnerable to injustice or are disproportionately affected by the pandemic and response measures, both in Canada and around the world. A conscious and deliberate questioning of assumptions is essential in ensuring that responses and decisions do not reproduce the biases and stereotypes that are further entrenching inequalities in this pandemic.

Promoting well-being and dignity

Individuals, organizations and communities have a duty to contribute to the welfare of others. In the context of COVID-19, the decisions and actions of public health authorities should promote and protect the physical, psychological and social health and well-being of all individuals and communities to the greatest extent possible. They should also consider the specific needs of, and duties toward, those who are marginalized, disadvantaged or disproportionately affected by response measures.

Non-maleficence and beneficence

The principle of non-maleficence asserts an obligation to avoid causing harm to others (individuals or groups) or to minimize risk of harm. The benefits being pursued and the need being addressed should outweigh any harms and the risk that they may occur. The principle of beneficence requires individuals, agencies and communities to contribute to the welfare of others. It entails a duty to promote the well-being of individuals and communities. One way this can be achieved is through the provision of beneficial actions, the prevention of harms and removing or reducing specific harms.

Minimizing harm

Public health authorities have an obligation to minimize the risk of harm and reduce suffering associated with COVID-19 and public health response measures. This requires taking into consideration the variety of harms and suffering that may result from the current pandemic (such as ill health, increased anxiety and distress, isolation, social and economic disruption). It also means taking into consideration the differential impact of these harms on different groups and populations.

Health equity is invoked through the application of respect for persons, communities and human rights, justice, promoting well-being and dignity, non-maleficence and beneficence, and minimizing harm. Recommendations in this report seek to reduce disparities in health and associated determinants, including social determinants. Given the importance of health equity principles in a pandemic situation, where therapeutics are in short supply, these considerations should prevail, as they also support the imperative to manage resources.

Where COVID-19 therapeutics are scarce, and the situation is critical, the application of these principles also helps manage the initial, limited supply of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir. Prioritizing a scarce supply of oral therapy to patients with the highest need and greatest likelihood of benefitting promotes the maximum overall benefit at a programmatic, population-based and clinical, individual-based level.

3 Deployment of a limited supply of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir to treat COVID-19

Treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 with nirmatrelvir/ritonavir can reduce the risk for progression to severe illness. Oral antivirals can also help reduce pressure on health care systems - and the burden of care - by making effective home-based care possible. Vaccination and other public health measures remain vital.

When COVID-19 therapeutic supply falls short of need due to the effects of a pandemic, developing criteria to inform prioritizing access to treatment is necessary to ensure resources are used efficiently and equitably.

3.1 Key considerations deploying a limited supply of oral antiviral medication to treat COVID-19

The high incidence of COVID-19 across the country (currently driven by the Omicron variant), the need to initiate treatment within 5 days of symptom onset (to attain benefit shown in studies), limited access to confirmatory testing, and the limited initial supply of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir give rise to practical challenges for prescribers and health systems.

Prioritization of patients most likely to benefit from oral antiviral therapy for COVID-19 helps manage scarce resources. The process should reflect explicit, transparent, clinical decision-making criteria based on a current understanding of prognostic indicators and vulnerability to severe health outcomes.

Provinces and territories and health care providers deploying the available supply of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir should consider implementing equity-enhancing measures. Social determinants of health are underlying factors that contribute to health disparities. Disparities may lead to increased exposure to the virus as well as poorer outcomes of COVID-19.

3.1.1 Clinical risk factor considerations

Certain clinical risk factors, including age, immunocompromised conditions, vaccination status, and the presence of one or more comorbidities have been associated with an increased likelihood of progression to more severe illness requiring hospitalization. Consideration of these factors may help jurisdictions to prioritize individuals who should receive nirmatrelvir/ritonavir while supply is limited, but should not replace a health care provider’s clinical judgment. (Note: most data in this document pre-date Omicron and continue to evolve).

Individuals in the following categories have the highest likelihood of severe illness and should be given priority for treatment given limited supply.

- Moderately to severely immunocompromised individuals not expected to mount an adequate response to SARS-CoV-2 infection, regardless of vaccinationFootnote 1 status.

- Individuals ≥80 years of age whose vaccinations are not up to date.

- Individuals ≥60 years of age residing in underserved, rural or remote communities, residing in a long-term care setting, or those living in or from First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities whose vaccinations are not up to date.

Footnotes

- Footnote 1

-

Refers to COVID-19 vaccines

Increasing age

Age is the strongest risk factor for progression to severe illness resulting in hospitalization and death from COVID-19. Since the beginning of the pandemic, adults 60 years and older have accounted for the highest proportion of hospitalization and death (COVID-19 daily epidemiology report).

Hospitalization rates also remain highest among fully vaccinated adults aged 80+ years. There are 1.6 million people aged 80+ in Canada. Another 2.8 million are aged 75 to 79.

- The Alberta Scientific Advisory Group conducted a rapid review to identify risk factors for severe COVID-19 outcomes. Age and vaccination status were identified as having the most impact on an individual’s risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19.

- A global systematic review and meta-analysis identified an age of 75 years and over to be associated with an increased risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes (Booth et al., 2021).

Immunocompromised conditions

Individuals who are immunocompromised are at increased risk for progression to severe illness that may result in hospitalization or death due to their inability to mount an adequate immune response to infection or vaccination. This includes individuals receiving cancer treatment, recipients of solid organ transplants and those with moderate to severe primary immunodeficiency. Table 1 provides selected examples of conditions associated with different risk of progression of COVID-19 to severe outcomes (refer to Supplemental Table 1 in the Annex for further information about the ranking of immunocompromised patients by numerous jurisdictions).

- Around 2,500 to 3,000 people received a solid organ transplant (SOT) each year for the period 2015-2019. Recipients generally receive lifelong treatment with immunosuppressants to counter organ rejection. However, immunosuppression is usually greatest for the first 3 to 6 months post-transplant (ublic Health Agency of Canada, 2021).

- Approximately 29,000 people in Canada suffer from primary immunodeficiency. Of these people, over 70% are undiagnosed (Immunodeficiency Canada, 2022).

- People Living with HIV (PLHIV) who are undiagnosed and/or untreated may be immunosuppressed. Among the 62,050 PLHIV in Canada, an estimated 13% (or 8,300 people) were not aware of their infection (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2021). A person living with HIV who is on treatment with an undetectable viral load (UVL) is not considered immunosuppressed.

| SEVERE risk | MODERATE risk | LOW risk |

|---|---|---|

| Cancer treatment | Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T-cell therapy | Type 1 diabetes |

| Solid organ transplant recipient | Advanced or untreated HIV | Controlled HIV infection (UVL) |

| Moderate to severe primary immunodeficiency | Active treatment with certain immunosuppressive therapies | |

| Stem cell transplant | Individuals receiving dialysis | |

Footnotes

|

||

Presence of 1 or more comorbidities

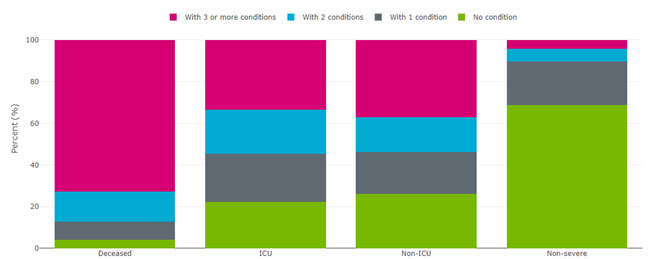

The presence of certain underlying medical conditions can increase the risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes (Kompaniyets et al., 2021). Risk increases as the number of comorbid conditions increases.

- Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) data show patients with comorbid conditions who were hospitalized with COVID-19 had longer hospital stays compared to patients without comorbidities. They were also more likely to require ICU care, and experienced higher in-hospital mortality (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2021).

- Over a dozen medical conditions have been identified as risk factors for the development of severe disease. A rapid review conducted by the Alberta Scientific Advisory Group found the risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes was increased in those with heart disease (including hypertension), chronic kidney disease, chronic respiratory disease, pregnancy, obesity, stroke, diabetes and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (Alberta Health Services, COVID-19 Scientific Advisory Group, 2021).

- Provincial data from British Columbia show the greatest risk of severe COVID-19 outcomes (adjusted risk ratios or hazard ratios above 2.5) included those with chronic kidney disease with an eGFR < 30, Down syndrome, and organ transplant recipients (BC Centre for Disease Control, 2021).

- A list of identified medical conditions supported by clinical evidence from systematic reviews and meta-analyses, and observational studies (cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional studies) can be found on the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s website (CDC, 2021).

- Comorbidities are very common and vary with regard to their impact on COVID-19 risk, compared to age, vaccination status, and serious immunocompromising conditions. Consideration of the risk(s) resulting from comorbidities will become more important operationally, as the supply of oral antivirals increases.

Vaccination status

Vaccination status has an impact on the risk of progression to severe illness that may result in hospitalization or death. There is ongoing scientific review of the evidence about the relative degree of immunity provided by factors such as the following:

- the number of vaccine doses received (for example, 2 doses versus 3)

- the time elapsed since vaccination; and

- previous SARS-CoV-2 infection

For the purposes of travellers seeking to enter Canada, the Public Health Agency of Canada defines fully vaccinated as “(having) received at least 2 doses of a vaccine accepted for travel or at least 1 dose of the Janssen/Johnson & Johnson vaccine”. However, as the science continues to evolve, definitions may evolve. Individual jurisdictions should continue to make their own decisions regarding who would be eligible to receive the treatment, taking vaccination status as part of their considerations.

While different jurisdictions may have different definitions for “fully vaccinated,” data show the unvaccinated and under-vaccinated population continue to have increased rates of hospitalization and death compared to the fully vaccinated population. In Canada, incidence of COVID-19 among the unvaccinated was 4.2 times higher than among the fully vaccinated in recent weeks (November 21 to December 18, 2021). From November 7 to December 4, 2021, when Delta was predominant in Canada:

- unvaccinated people aged 12 to 59 were 25 times more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19 than fully vaccinated people; and

- unvaccinated people aged 60 years or older were 16 times more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19 than fully vaccinated people

Clinical assessment should include documentation of vaccination status.

- The UK Health Security Agency published a report on December 31, 2021, showing the risk of hospitalization for individuals infected with the Omicron variant was 65% lower in those who had received 2 doses of a vaccine, and 81% lower in those who had received 3 doses, compared to those who had not received any vaccination (UKHSA, 2021). Further information from this report, including comparative effectiveness of vaccines against the Delta and Omicron variants can be found in the Annex.

- Brief information from studies on the effectiveness of vaccines against the Omicron variant, and statements from the manufacturers of mRNA vaccines can also be found in the Annex.

3.1.2 Programmatic considerations related to social and economic determinants of health

Use of the limited supply of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir should proactively address barriers to accessing care and mitigate health disparities in COVID-19 outcomes, in addition to considering clinical risk factors.

Racial and socioeconomic disparities in the rates of SARS-CoV-2 infection, and COVID-19-related hospitalization and mortality, have been identified. Non-medical factors such as socioeconomic status, Indigeneity, race/ethnicity, occupation, homelessness and incarceration, are factors with the potential to increase risk and severity of COVID-19-related outcomes (Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion, 2020). These relationships are complex and may be related to social conditions that increase the prevalence of pre-existing underlying medical conditions and/or decreased access to health care for some populations. For example, many Indigenous communities face structural inequalities that hinder their well-being and create barriers in access to care (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2021).

Geographic isolation can lead to difficulty in accessing medical care. Individuals living in rural and remote communities could, as a result, experience worse health outcomes from COVID-19. Many Canadian jurisdictions have identified rural and remote communities where residents are at higher risk due to factors such as inadequate housing, limited access to healthcare, pre-existing medical conditions, food insecurity, water quality etc. For example, a Manitoba study highlighted individuals living in remote Northern regions, low-income neighbourhoods and in long-term care were the most at risk of SARS-CoV-2 and at increased risk of severe COVID-19 (Righolt, Zhang, Sever, Wilkinson, & Salaheddin, 2021).

Special accommodations should be provided for people with disabilities (Ofner, et al., 2021). People with intellectual and physical disabilities are often at increased risk of acquiring SARS-CoV-2 infection and having poor outcomes from COVID-19. They also:

- have reduced access to routine health care and rehabilitation; and

- are more vulnerable to the adverse social impacts of public health efforts to mitigate the negative effects of the pandemic (Shakespeare, Ndagire, & Seketi, 2021)

Key public health interventions (e.g., vaccination, testing) and treatments should be aimed at reaching all populations, including those who are hard to reach and those who are less likely to seek out care. Members of underserved communities who are at elevated risk of severe outcomes of COVID-19 may face significant barriers to testing and care (for example, transportation, health literacy, language barrier or lack of a healthcare provider).

There is evidence that vaccination campaigns, including the use of mobile and walk-up sites, improved both accessibility and coverage for hard-to-reach populations (Hernandez, Karletsos, Avegno, & Reed, 2021). Jurisdictions may be able to leverage experience and best practices with their vaccination programs and the crossover with therapeutics to determine the best way to reach underserved populations. For example, the use of combined testing, assessment and treatment centres could potentially increase access to treatment for vulnerable or hard to reach populations. Local public health departments with their knowledge of access issues and communities in need, and their own systems, could help facilitate linkage to testing and treatment.

3.1.3 Additional considerations in the deployment of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir

- Confirming SARS-CoV-2 infection

The presentation of other infections may resemble COVID-19. Therefore, laboratory confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 infection should inform the decision to use nirmatrelvir/ritonavir. This may require prioritized access to reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) testing for high-risk populations. Jurisdictions may opt to include essential health care workers as a group that should have priority for testing to help assure health care remains available to the public.

Health care professional-confirmed rapid testing protocols (whether RAT or preferably a rapid molecular test [nucleic acid amplification test or NAAT]) may be considered confirmatory of SARS-CoV-2 infection in areas with high prevalence of COVID-19 or in a symptomatic person who has had close contact to an individual with confirmed COVID-19.

In the context of a shortage of therapeutics, treatment on the basis of a clinical diagnosis is discouraged and should be avoided.

- Need to initiate treatment within 5 days of symptom onset

Treatment must be initiated within 5 days of symptom onset in order to attain benefit shown in clinical trials; the drug is not expected to provide benefit if initiated later in the course of illness. Refer to the product monograph for details.

A system that links individuals with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-19 to treatment can help maximize the benefits of therapy, by ensuring that treatment is initiated as early as possible within the 5 day window.

- Lack of public awareness of the availability of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir

Individuals with mild to moderate COVID-19 symptoms may simply stay home, as currently instructed by some jurisdictional or local recommendations, and not seek care. They may not be aware of the benefits of treatment with nirmatrelvir/ritonavir. Communications to the public will be essential if the roll-out is to be successful.

- Drug interactions and eligibility criteria

Given the numerous significant and serious drug interactions with nirmatrelvir/ritonavir, a thorough medication history should be taken by a qualified health care provider for each patient before prescribing and dispensing nirmatrelvir/ritonavir. The best treatment option should be assessed for the individual to help manage the limited supply.

Consult the product monograph for indications and conditions of use and safety considerations, as well as guidance on dose adjustment for individuals with renal impairment. Similarly, patients should be assessed for contra-indications and other risks. A checklist of eligibility criteria could be developed to facilitate the clinical assessment of patients and ensure concordance with jurisdictional guidance.

- Alternate treatment

Consideration should be given to the availability of other effective treatment options to help manage the limited supply of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir for individuals who do not have access to other effective treatments or for whom they are not appropriate.

Health Canada has approved several treatments for mild-to moderate COVID-19 in non-hospitalized patients at risk of severe illness: bamlanivimab, casirivmab/imdevimab, and sotrovimab. Alternate COVID-19 treatment protocols such as these monoclonal antibodies should be considered, when feasible and appropriate, based on available infrastructure and viral genotyping. Because these require intravenous administration there are logistical constraints to administering them in many settings. Of these, only sotrovimab is expected to be effective against the Omicron variant. Laboratory studies show a loss of activity for bamlanivimab and casirivimab/imdevimab against this variant.

- Distribution

When and where appropriate, community pharmacies and rural community centres could be considered for prescribing and dispensing nirmatrelvir/ritonavir. Adequate resources need to be available to incorporate the appropriate necessary clinical assessment of patients (including drug interaction assessments). A centralized approach with a hub and spoke model for prescribers could facilitate broad access. Identification of designated/authorized prescribers who will be prescribing nirmatrelvir/ritonavir could be considered to target populations, maximize impact and monitor treatment outcomes.

Given the duty to lessen the impact of social inequities on COVID-19 outcomes in disadvantaged communities, a greater supply of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir could be deployed to the most vulnerable communities, including those with:

- reduced access to health care (including tertiary care)

- limited ability to adopt COVID-19 preventive measures (e.g., congregate living settings); and

- high prevalence of known COVID-19 risk factors (e.g., untreated chronic disease, intellectual or physical disabilities)

- Surveillance and monitoring

It will be important to collect a consistent core set of COVID-19 outcome data for events of hospitalization, ICU admissions and death for those treated with nirmatrelvir/ritonavir. These data would be used to evaluate this drug’s impact on patients and thus help to revise prioritization criteria. Factors such as age, vaccination status, geographic area (rural versus. urban) and the presence of comorbidities could be incorporated in the data collection. Outcome data should be centralized and ideally available in real-time for healthcare practitioners to consult. Jurisdictions should establish a safety reporting system to monitor use and unexpected safety events.

4 Interim considerations - summary

The initial limited supply of nirmatrelvir/ritonavir should be prioritized for those who are at the highest risk for severe illness. Based on currently available data, age is the strongest risk factor for severe illness, and hospitalization rates among the vaccinated are highest for those aged 80 and older. Within older age groups, those who are unvaccinated or whose vaccinations are not up to date are at highest risk. Individuals who are moderately to severely immunocompromised are unable to mount a response to vaccination and infection, and should also be prioritized for treatment. As supply permits, the prioritization criteria should be expanded to include other populations at increased risk of severe illness.

Consideration should be given to making a greater supply available for use in rural and remote communities where there is limited access to tertiary care, and where such factors as food insecurity, inadequate housing and a higher level of pre-existing medical conditions may increase the risk of worse health outcomes from COVID-19. Special populations, such as individuals with developmental or physical disabilities, often experience barriers to testing and care and may be at risk of worse outcomes from COVID-19. Thus, their needs should be considered in planning for implementation.

Infection should be confirmed before initiating treatment, ideally by RT-PCR testing. If this is not possible or if results would not be available until more than 5 days from symptom onset, rapid antigen tests may be used. In the context of very limited supply, treatment on the basis of a clinical diagnosis should be avoided.

Acknowledgements

The Public Health Agency of Canada gratefully acknowledges the contribution of the following individuals who generously gave their time and shared their expertise.

- Dr. Lisa Barrett

- Clinician Investigator and Assistant Professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Department of Microbiology & Immunology and Department of Pathology, Dalhousie University

- Dr. Perry Gray

- Chief Medical Officer, Shared Health, Provincial Lead, Medical Specialist Services, Health Sciences Centre, Winnipeg

- Dr. Todd C. Lee

- Associate Professor, Department of Medicine, McGill University

- Dr. Andrew M. Morris

- Medical Director, Antimicrobial Stewardship Program, Sinai Health, University Health Network; Professor, Department of Medicine; Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto

- Dr. Srinivas Murthy

- Associate Professor, Department of Paediatrics, University of British Columbia

- Dr. Lynora Saxinger

- Professor of Infectious Diseases, Departments of Medicine and Medical Microbiology and Immunology, University of Alberta, co-Chair COVID-19 Scientific Advisory Group (to AHS/Emergency Coordination Centre), Medical Lead AHS Antimicrobial Stewardship Northern Alberta

- Dr. Diego Silva

- Senior Lecturer in Bioethics, Sydney Health Ethics, University of Sydney School of Public Health, Chair of the Public Health Ethics Consultative Group (PHECG), Public Health Agency of Canada

- Dr. Maxwell Smith

- Assistant Professor, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Western Ontario, member of the Public Health Ethics Consultative Group (PHECG) at the Public Health Agency of Canada

Observers

- Amanda Allard

- Director, Pharmaceutical Reviews, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health

- Dominic Belanger

- Directeur par intérim, direction des affaires pharmaceutiques et du médicament, ministère de la Santé et des Services sociaux

- Sylvie Bouchard

- Direction de l’évaluation des médicaments et des technologies à des fins de remboursement, Institut national d'excellence en santé et en services sociaux

- Peter Dyrda

- Interim Manager, Program & Policy Development, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health

- Brent Fraser

- Vice-President, Pharmaceutical Reviews, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health

- Mélanie Tardif

- Coordonnatrice scientifique en santé, Direction de l’évaluation et de la pertinence des modes d’intervention en santé, Institut national d'excellence en santé et en services sociaux

And the following contributors from the Public Health Agency of Canada, Infectious Diseases Programs Branch, Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control, COVID-19 Therapeutics:

- Dr. Howard Njoo

- Bersabel Ephrem

- Jacqueline Arthur

- Dr. Margaret Gale-Rowe

- Jane Kolbe

- Mina Azad

- Serena Cortés-Kaplan

- Lizanne Béïque

- Stacy Sabourin

Annex

Key risk factors associated with severe outcomes to COVID-19 infection

Immunocompromised conditions

| Reference | Purpose of ranking | Ranking |

|---|---|---|

COVID-19 vaccine- booster dose |

|

|

COVID-19 vaccine- booster dose |

|

|

COVID-19 vaccine- booster dose |

|

|

COVID-19 vaccine- booster dose |

|

|

COVID-19 vaccine- booster dose |

|

|

Alberta Health Services, COVID-19 Scientific Advisory Group, 2021 |

SAG |

Note: Young patients with autoimmune disease in remission without additional medical comorbidities are likely not at increased risk of severe outcomes of COVID-19. |

Increasing age

| Age group | Mortality Rate per 1,000,000 | Relative Mortality Risk |

|---|---|---|

| 0-17 years | 0 | n/a |

| 18-34 years | 0.8 | Comparison group |

| 35-44 years | 8.8 | 11x higher |

| 45-54 years | 25.5 | 30x higher |

| 55-64 years | 59.8 | 71x higher |

| 65-74 years | 238.2 | 284x higher |

| 75-84 years | 955.6 | 1,139x higher |

| 85+ years | 4,620.9 | 5,506x higher |

| Age group | Hospitalization | Death |

|---|---|---|

| 0-4 years | <1x | <1x |

| 5-17 years | <1x | <1x |

| 18-29 years | Reference group | Reference group |

| 30-39 years | 2x | 4x |

| 40-49 years | 2x | 10x |

| 50-64 years | 4x | 25x |

| 65-74 years | 5x | 65x |

| 75-84 years | 8x | 150x |

| 85+ years | 10x | 370x |

Presence of one or more comorbidities

Supplemental figure 1. Percent of COVID-19 cases with no pre-existing conditions, one condition, 2 conditions or 3 or more conditions by case severity, all age groups and both sexes combined, all Alberta patients. Pre-existing conditions included are: diabetes, hypertension, COPD, cancer, dementia, stroke, liver cirrhosis, cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, and immune-deficiency. Last updated January 13, 2022 from Alberta, 2022.

Figure 1 - Long description

| Number of pre-existing conditions | Non-Severe | Non-ICU | ICU | Deaths | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | Number | Percent | |

| No condition | 291446 | 69.6% | 3157 | 26.3% | 512 | 22.3% | 145 | 4.3% |

| With 1 condition | 85262 | 20.4% | 2385 | 19.8% | 537 | 23.4% | 287 | 8.5% |

| With 2 conditions | 24919 | 6.0% | 2006 | 16.7% | 486 | 21.2% | 485 | 14.3% |

| With 3 or more conditions | 17179 | 4.1% | 4469 | 37.2% | 757 | 33.0% | 2463 | 72.9% |

Supplemental figure 2. COVID-19 hospitalizations and associated characteristics by comorbidity and age group among Canadian patients from April to June 2021. Accessed from downloadable data tables from Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2021.

| Metric | Younger than age 65 | Age 65 and older | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Younger than age 65 Without comorbidity |

Younger than age 65 With comorbidity |

Age 65 and older Without comorbidity |

Age 65 and older With comorbidity |

Total Without comorbidity |

Total With comorbidity |

|

| Average total length of stay (days) | 7.5 | 16.0 | 12.8 | 19.2 | 9.0 | 17.9 |

| In-facility death rate (%) | 2.4 | 12.5 | 13.2 | 25.3 | 5.4 | 20.0 |

| In-hospital deaths (number) | 321 | 471 | 679 | 1,337 | 1,000 | 1,808 |

| Hospitalizations (number) | 13,340 | 3,768 | 5,132 | 5,284 | 18,472 | 9,052 |

| ICU admissions (%) | 22.4 | 45.9 | 22.6 | 29.4 | 22.4 | 36.2 |

| ICU admissions (number) | 2,981 | 1,728 | 1,158 | 1,552 | 4,139 | 3,280 |

| Hospitalizations with ventilation (%) | 13.9 | 33.6 | 14.8 | 20.7 | 14.1 | 26.0 |

| Hospitalizations with ventilation (number) | 1,851 | 1,265 | 761 | 1,091 | 2,612 | 2,356 |

|

Notes These results are based on provisional data and should be interpreted with caution. Refer to the Notes to readers tab for more information on provisional data findings. Excludes data from Quebec. COVID-19 hospitalizations include both confirmed and suspected cases with any diagnosis type. Comorbidity results are based on the presence of the following significant diagnoses: hypertension, heart disease, congestive heart failure, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, rheumatologic disease, mild liver disease, moderate or severe liver disease, diabetes with chronic complications, hemiplegia or paraplegia, renal disease, AIDS/HIV, any malignancy including lymphoma or leukemia, and metastatic solid tumour. This hospitalization data is based on discharged patients and may differ from the number of patients in hospital on a specific day. Source Discharge Abstract Database, 2021–2022, Canadian Institute for Health Information. |

||||||

Supplemental figure 3. COVID-19 hospitalizations and associated characteristics by comorbidity and income quintile among Canadian patients from April to June 2021. Accessed from downloadable data tables from Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2021.

| Neighbourhood income quintile | Number of hospitalizations | Average total length of stay (days) | In-facility death rate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of hospitalizations Without comorbidity |

Number of hospitalizations With 1 comorbidity |

Number of hospitalizations With 2+ comorbidities |

Average total length of stay (days) Without comorbidity |

Average total length of stay (days) With 1 comorbidity |

Average total length of stay (days) With 2+ comorbidities |

In-facility death rate Without comorbidity |

In-facility death rate With 1 comorbidity |

In-facility death rate With 2+ comorbidities |

|

| Q1 (least affluent) | 5,074 | 2,025 | 816 | 9.2 | 16.6 | 25.2 | 6.1 | 16.2 | 28.9 |

| Q2 | 3,967 | 1,400 | 620 | 9.3 | 15.9 | 22.5 | 5.9 | 17.1 | 27.4 |

| Q3 | 3,634 | 1,253 | 493 | 9.1 | 16.3 | 20.8 | 5.3 | 16.7 | 28.6 |

| Q4 | 3,036 | 942 | 351 | 8.3 | 14.2 | 21.4 | 4.7 | 16.7 | 27.6 |

| Q5 (most affluent) | 2,258 | 722 | 257 | 8.8 | 16.1 | 21.2 | 4.4 | 15.9 | 30.7 |

|

Notes These results are based on provisional data and should be interpreted with caution. Refer to the Notes to readers tab for more information on provisional data findings. Excludes cases with unknown neighbourhood income quintile. Excludes data from Quebec. COVID-19 hospitalizations include both confirmed and suspected cases with any diagnosis type. Comorbidity results are based on the presence of the following significant diagnoses: hypertension, heart disease, congestive heart failure, dementia, chronic pulmonary disease, rheumatologic disease, mild liver disease, moderate or severe liver disease, diabetes with chronic complications, hemiplegia or paraplegia, renal disease, AIDS/HIV, any malignancy including lymphoma or leukemia, and metastatic solid tumour. This hospitalization data is based on discharged patients and may differ from the number of patients in hospital on a specific day. Source Discharge Abstract Database, 2021–2022, Canadian Institute for Health Information. |

|||||||||

Risk factor criteria from phase 3 nirmatrelvir/ritonavir trial: EPIC-HR

- 18 years of age and older with certain medical conditions. High risk is defined as patients who meet at least one of the following criteria:

- older age (e.g., 60 years of age and older)

- obesity

- current smoker

- chronic kidney disease

- sickle cell disease

- diabetes

- immunosuppressive disease or treatment

- cardiovascular disease or hypertension

- chronic lung diseaseor

- active cancer

Additional information on vaccine effectiveness and Omicron

Studies and manufacturer statements on the efficacy of their vaccines against the Omicron variant:

BNT162b2: BioNTech, Pfizer vaccine

Three doses of the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine result in neutralizing the Omicron variant, equivalent to that reported in sera from persons who received 2 doses of the vaccine against the wild type (Pfizer, 2021).

A 2 dose regimen of the Pfizer vaccine is 70% effective against hospitalization due to the Omicron COVID-19 variant, compared to 93% for the Delta dominating period examined (Collie, Champion, Moultrie, Bekker, & Gray, 2021).

Compared to unvaccinated individuals, among those who recently had their second vaccine dose, Pfizer's and Moderna's efficacy against Omicron was 55.2 percent and 36.7 percent, respectively. This protection waned off over 5 months (Hansen, et al., 2021).

mRNA-1273 (aka Spikevax): Moderna vaccine

It was reported that a 50 microgram booster increased neutralizing antibody levels against Omicron 37-fold when compared to pre-boost levels. A 100 microgram booster dose increased neutralizing antibody levels by an astounding 83-fold (Moderna, 2021).

Update on hospitalization and vaccine effectiveness for Omicron VOC-21NOV-01 (B.1.1.529)

The risk of hospitalization for Omicron cases was 65% lower in individuals who had received 2 doses of a vaccine than in those who had not received any vaccination. The risk of hospitalization for Omicron infection was much lower among individuals who received 3 vaccination doses (81% lower) (UKHSA, 2021).

| Vaccination status | Omicron HR (95% CI) | Delta HR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Unvaccinated/<28 days since first vaccine | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| ≥28 days since first vaccine dose | 1.02 (0.72-1.44) | 0.42 (0.36-0.48) |

| ≥14 days since second vaccine dose | 0.35 (0.29-0.43) | 0.18 (0.17-0.19) |

| ≥14 days since third vaccine dose | 0.19 (0.15-0.23) | 0.15 (0.13-0.16) |

One vaccination dose reduced hospitalization by 35% among symptomatic Omicron variant patients, 2 doses by 67% up to 24 weeks and 51% up to 25 weeks, and 3 doses by 68%. When combined with vaccination efficacy against symptomatic disease, this amounted to vaccine efficacy against hospitalization of 52% after one dose, 72% 2 to 24 weeks after dose 2, 52% 25+ weeks after dose 2, and 88% 2+ weeks after a booster dose.

| Dose | Interval after dose | OR against symptomatic disease (95% CI) | HR against hospitalisation (95% CI) | VE against hospitalisation (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4+ weeks | 0.74 (0.70-0.77) | 0.65 (0.30-1.42) | 52% (-5-78) |

| 2 | 2-24 weeks | 0.82 (0.80-0.84) | 0.33 (0.21-0.55) | 72% (55-83) |

| 2 | 25+ weeks | 0.98 (0.95-1.00) | 0.49 (0.30-0.81) | 52% (21-71) |

| 3 | 2+ weeks | 0.37 (0.36-0.38) | 0.32 (0.18-0.58) | 88% (78-93) |

Additional Resources

Awareness

- Government of Canada - Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): Awareness resources

- PHAC - COVID-19 daily epidemiology update

- Canadian Institute for Health Information - COVID-19 hospitalization and emergency department statistics

Risk assessment for severe COVID-19 outcomes

- BC Centre for Disease Control – Risk Factors for Severe Disease

- COVID-19 Scientific Advisory Group, Alberta Health Services - Rapid Evidence Report: Risk Factors for Severe COVID-19 Outcomes

- U.S. Centre for Disease Control and Prevention - Science Brief: Evidence Used to Update the List of Underlying Medical Conditions Associated with Higher Risk for Severe COVID-19

Treatment

- NIH COVID-19 Treatment Guidelines Statement on Patient Prioritization for Outpatient Therapies

- FDA Fact Sheet for Healthcare Providers: Emergency Use Authorization for Paxlovid

- European Medicines Agency Assessment Report for Paxlovid for the treatment of COVID-19

- EPIC-HR: Study of Oral PF-07321332/Ritonavir Compared With Placebo in Nonhospitalized High Risk Adults With COVID-19 (NCT04960202)

- The British Columbia COVID-19 Therapeutics Committee – Clinical Guidance

- Alberta Health Services – Outpatient Treatment for COVID-19

- Saskatchewan – Monoclonal Antibody Treatment

- Manitoba – Treatment for COVID-19

- Ontario COVID-19 Drugs and Biologics Clinical Practice Guidelines Working Group - Clinical Practice Guideline Summary: Recommended Drugs and Biologics in Adult Patients with COVID-19

- INESSS – TRAITEMENTS SPÉCIFIQUES À LA COVID-19

- A living WHO guideline on drugs for COVID-19

- Australian Disease Modifying Treatments for Adults with COVID-19

- Outpatient therapies for COVID-19: How do we choose?

Drug Interactions

- Liverpool COVID-19 Drug Interactions

- FDA Fact Sheet for Healthcare Providers: Emergency Use Authorization for Paxlovid, Section 7: Drug Interactions (page 9 to 15).

- Health Canada Paxlovid Product Monograph (page 14 to 27)

- Paxlovid (nirmatrelvir and ritonavir) - Dosing and Dispensing in Renal Impairment, Risk of Serious Adverse Reactions Due to Drug Interactions, and English-Only Labels

Testing

Health Equity

- An Ethical Framework for Allocating Scarce Inpatient Medications for COVID-19 in the US

- Considerations for planning COVID-19 treatment services in humanitarian responses

- Ethical Framework for Allocating Scarce Drug Therapies During COVID-19

- Ethical Dimensions of Public Health Actions and Policies With Special Focus on COVID-19

- Ethically Allocating COVID-19 Drugs Via Pre-approval Access and Emergency Use Authorization

- Fair Allocation of Scarce Medical Resources in the Time of Covid-19

- Fair allocation of scarce therapies for COVID-19

- Key populations for early COVID-19 immunization: preliminary guidance for policy

- Preparing for the Authorization of COVID-19 Antivirals

- The COVID-19 pandemic and health inequalities

- WHO: Ethics and COVID-19: resource allocation and priority-setting

References

Alberta. (2022, January 11). COVID-19 Alberta statistics. Retrieved from Alberta: https://www.alberta.ca/stats/covid-19-alberta-statistics.htm#pre-existing-conditions

Alberta Health Services, COVID-19 Scientific Advisory Group. (2021, November 19). COVID-19 Scientific Advisory Group Rapid Evidence Report Risk Factors for Severe COVID-19 Outcomes. Retrieved from Alberta Health Services: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/ppih/if-ppih-covid-19-sag-risk-factors-for-severe-covid-19-outcomes-rapid-review.pdf

BC Centre for Disease Control. (2021, December 10). Risk Factors for Severe COVID-19 Disease. Retrieved from BC Centre for Disease Control: http://www.bccdc.ca/health-professionals/clinical-resources/covid-19-care/clinical-care/risk-factors-severe-covid-19-disease

Booth, A., Reed, A., Ponzo, S., Yassaee, A., Aral, M., Plans, D., & Labrique, A. (2021). Population risk factors for severe disease and mortality in COVID-19: A global systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, e0247461.

British Columbia. (2022, January 5). How to get vaccinated for COVID-19. Retrieved from British Columbia: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/covid-19/vaccine/register#immunocompromised

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2021, October 28). COVID-19 hospitalization and emergency department statistics. Retrieved from Canadian Institute for Health Information: https://www.cihi.ca/en/covid-19-hospitalization-and-emergency-department-statistics

CDC. (2021, November 22). Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death By Age Group. Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-age.html

CDC. (2021, October 14). Science Brief: Evidence Used to Update the List of Underlying Medical Conditions Associated with Higher Risk for Severe COVID-19. Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/science/science-briefs/underlying-evidence-table.html

CDC. (2022, January 7). COVID-19 Vaccines for Moderately or Severely Immunocompromised People. Retrieved from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/recommendations/immuno.html

Collie, S., Champion, J., Moultrie, H., Bekker, L.-G., & Gray, G. (2021). Effectiveness of BNT162b2 Vaccine against Omicron Variant in South Africa. New England Journal of Medicine, c2119270.

Hansen, C., Schelde, A., Mousten-Helm, I., Emborg, H.-D., Krause, T., Molbak, K., & Valentiner-Branth, P. (2021). Vaccine effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 infection with the Omicron or Delta variants following a two-dose or booster BNT162b2 or mRNA-1273 vaccination series: A Danish cohort study. medRxiv.

Hernandez, J. H., Karletsos, D., Avegno, J., & Reed, C. H. (2021). Is Covid-19 community level testing effective in reaching at-risk populations? Evidence from spatial analysis of New Orleans patient data at walk-up sites. BMC Public Health, 632.

Immunodeficiency Canada. (2022, January 13). Primary Immunodeficiency (PI). Retrieved from Immunodeficiency Canada: https://immunodeficiency.ca/primary-immunodeficiency/primary-immunodeficiency-pi/

Kompaniyets, L., Pennington, A. F., Goodman, A. B., Rosenblum, H. G., Belay, B., Ko, J. Y., & Chevinsky, J. R. (2021). Underlying Medical Conditions and Severe Illness Among 540,667 Adults Hospitalized With COVID-19, March 2020–March 2021. Preventing Chronic Disease, 210123. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd18.210123

Moderna. (2021, December 20). MODERNA ANNOUNCES PRELIMINARY BOOSTER DATA AND UPDATES STRATEGY TO ADDRESS OMICRON VARIANT. Retrieved from Moderna: https://investors.modernatx.com/news/news-details/2021/Moderna-Announces-Preliminary-Booster-Data-and-Updates-Strategy-to-Address-Omicron-Variant/default.aspx

National Advisory Committee on Immunization. (2021, February 12). Archived: Guidance on the prioritization of key populations for COVID-19 immunization [2021-02-12]. Retrieved from Goverment of Canada: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/immunization/national-advisory-committee-on-immunization-naci/guidance-prioritization-key-populations-covid-19-vaccination.html

Nova Scotia. (2022, January 13). Coronavirus (COVID-19): immunocompromised. Retrieved from Nova Scotia: https://novascotia.ca/coronavirus/immunocompromised/

Ofner, M., Salvadori, M., Pucchio, A., Chung, Y.-E., House, A., & PHAC COVID-19 Clinical Issues Task Group. (2021, June 21). COVID-19 and people with disabilities in Canada. Retrieved from Government of Canada: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/guidance-documents/people-with-disabilities.html

Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion. (2020, May 24). COVID-19 – What We Know So Far About…Social Determinants of Health. Retrieved from Public Health Ontario: https://www.publichealthontario.ca/-/media/documents/ncov/covid-wwksf/2020/05/what-we-know-social-determinants-health.pdf?la=en

Ontario Ministry of Health. (2022, January 13). COVID-19 Vaccine Third Dose. Retrieved from Ontario: https://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/pro/programs/publichealth/coronavirus/docs/vaccine/COVID-19_vaccine_third_dose_recommendations.pdf

Pfizer. (2021, December 8). Pfizer and BioNTech Provide Update on Omicron Variant. Retrieved from Pfizer: https://www.pfizer.com/news/press-release/press-release-detail/pfizer-and-biontech-provide-update-omicron-variant

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2021, June 28). Estimates of HIV incidence, prevalence and Canada’s progress on meeting the 90-90-90 HIV targets. Retrieved from Government of Canada: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/summary-estimates-hiv-incidence-prevalence-canadas-progress-90-90-90.html

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2021, December 23). Immunization of immunocompromised persons: Canadian Immunization Guide. Retrieved from Goverment of Canada: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/canadian-immunization-guide-part-3-vaccination-specific-populations/page-8-immunization-immunocompromised-persons.html#a21

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2021, February 16). Public health ethics framework: A guide for use in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. Retrieved from Govermnent of Canada: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/diseases/2019-novel-coronavirus-infection/canadas-reponse/ethics-framework-guide-use-response-covid-19-pandemic.html

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2021, March 3). What we heard: Indigenous Peoples and COVID-19: Public Health Agency of Canada’s companion report. Retrieved from Goverment of Canada: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/publications/chief-public-health-officer-reports-state-public-health-canada/from-risk-resilience-equity-approach-covid-19/indigenous-peoples-covid-19-report.html

Public Health Agency of Canada. (2022, January 13). COVID-19 daily epidemiology update. Retrieved from Goverment of Canada: https://health-infobase.canada.ca/covid-19/epidemiological-summary-covid-19-cases.html

Righolt, C. H., Zhang, G., Sever, E., Wilkinson, K., & Salaheddin, M. M. (2021). Patterns and descriptors of COVID-19 testing and lab-confirmed COVID-19 incidence in Manitoba, Canada, March 2020-May 2021: A population-based study. The Lancet Regional Health - Americas, 100038.

Shakespeare, T., Ndagire, F., & Seketi, Q. S. (2021, April 10). Triple jeopardy: disabled people and the COVID-19 pandemic. COMMENT, 397(10282), P1331-1333. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00625-5

UKHSA. (2021, December 31). SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern and variants under investigation in England: Omicron update . Retrieved from UK Health Security Agency: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1045619/Technical-Briefing-31-Dec-2021-Omicron_severity_update.pdf