Lyme disease: For health professionals

On this page

- Key information

- Transmission

- Clinical manifestations

- Diagnosis

- Treatment

- Laboratory testing

- Surveillance

- Subscribe to the Zoonoses Bulletin

Key information

Lyme disease is a tick-borne zoonotic disease caused by the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi (B. burgdorferi). B. burgdorferi is a spirochete bacterium and is mainly transmitted by infected blacklegged ticks (Ixodes scapularis) and western blacklegged ticks (Ixodes pacificus). Consult with provincial or territorial public health authorities to find out where ticks are most likely to be found.

Lyme disease, like most tick-borne disease infections, occurs during the warmer months, but infections can occur throughout the year. Ticks can be active whenever the temperature is consistently above freezing, and the ground isn't covered by snow.

It's critical to remove attached ticks promptly as the risk of transmission of B. burgdorferi increases the longer the tick is attached. Infected blacklegged ticks and western blacklegged ticks typically need to be attached for at least 24 hours to transmit B. burgdorferi.

Individuals may not be aware of or remember being bitten by a tick. Therefore, it's important that health professionals conduct a detailed patient history, including history of exposure to ticks when assessing individuals with signs or symptoms suggestive of Lyme disease.

Treatment shouldn't be delayed while waiting for confirmatory laboratory results. Most cases of Lyme disease can be managed successfully with a timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment.

There's currently no vaccine to prevent Lyme disease. The best way to prevent tick-borne diseases is to prevent tick bites.

Lyme disease is the most common tick-borne disease in Canada. However, for individuals presenting with similar signs or symptoms, we encourage health professionals to consider the possibility of other tick-borne diseases, such as:

- babesiosis

- anaplasmosis

- Powassan virus disease

- tick-borne relapsing fever

Learn more about:

- Ticks in Canada

- How to remove a tick

- How to prevent tick bites

- Provincial and territorial public health authorities

Transmission

Lyme disease is primarily acquired through the bite of an infected tick. The ticks known to transmit Lyme disease are:

blacklegged tick (Ixodes scapularis), also known as deer tick

Source: Institut national de santé publique du Québec

western blacklegged tick (Ixodes pacificus)

Source: British Columbia Centre for Disease Control

In most cases, transmission of B. burgdorferi occurs after at least 24 hours of attachment of an infected tick.

In North America, B. burgdorferi is the most common cause of Lyme disease infection, with Borrelia mayonii occurring rarely in the north-central United States.

In Europe and Asia, B. afzelii or B. garinii are the most common cause of infection, with B. burgdorferi being the less common cause.

Learn more about:

Clinical manifestations

The incubation period for early localized Lyme disease is 3 to 30 days.

Symptoms may be absent or range from mild to severe, and may progress over time, particularly in untreated individuals.

Individuals who develop symptoms days or weeks after a tick bite may not remember being bitten or associate symptoms with the bite.

Clinical manifestations aren't necessarily specific to the stage of infection. They can overlap and form a continuum in some untreated patients.

Early localized Lyme disease (3 to 30 days)

Early localized Lyme disease usually presents as an acute illness characterized by:

- flu-like symptoms, such as:

- fever

- malaise

- myalgia

- headache

- migratory arthralgia

- lymphadenopathy

- erythema migrans rash

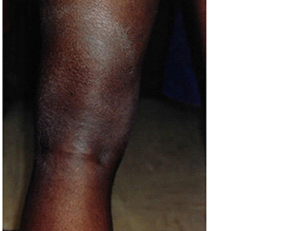

Erythema migrans rash

Most individuals with Lyme disease infection will present with an erythema migrans rash greater than 5 cm in diameter at the site of the tick bite. This rash usually presents within 7 days of the initial tick bite but can range from 3 to 30 days. It's usually painless and non-pruritic. In many cases, an erythema migrans rash may not present with a classic bull's-eye appearance.

On dark skin, erythema migrans may have the appearance of a bruise.

Hypersensitivity reaction to a tick bite

Individuals may develop a hypersensitivity reaction within 24 hours of a tick bite. A hypersensitivity reaction will produce an erythematous skin lesion less than 5 cm in diameter which doesn't expand and usually recedes within 48 hours.

Hypersensitivity skin reactions shouldn't be confused with erythema migrans. Individuals who develop erythematous skin lesions which haven't resolved within 48 hours should be reassessed to determine whether an erythema migrans rash has developed.

Images of erythema migrans rash

Early disseminated Lyme disease (less than 3 months)

If untreated, B. burgdorferi can:

- disseminate via the bloodstream and lymphatic system to other body sites

- cause damage to body tissues at those sites, most commonly nervous and musculoskeletal systems

Signs and symptoms can include:

- fatigue and general weakness

- multiple erythema migrans lesions

- neurological manifestations

- aseptic meningitis

- cranial neuropathy, especially facial nerve palsy (Bell's palsy)

- encephalitis, encephalomyelitis, subtle encephalopathy or pseudotumor cerebri (all rare)

- motor and sensory radiculoneuropathy and mononeuritis multiplex

- subtle cognitive difficulties

- Lyme carditis, which may manifest as:

- high-degree atrioventricular block (the most common presentation)

- sinus node disease or dysfunction

- intra-atrial block

- atrial fibrillation

- supraventricular tachycardia

- bundle branch block

- ventricular tachycardia and fibrillation

Rare manifestations of early disseminated Lyme disease include:

- conjunctivitis

- keratitis

- mild hepatitis

- splenomegaly

- uveitis

Late disseminated Lyme disease (more than 3 months)

If diagnosis is delayed or Lyme disease remains untreated, it can persist for months or years.

Musculoskeletal manifestations can include:

- intermittent or persistent episodes of pain and/or swelling in 1 or multiple joints, particularly the knees and other large joints, which can lead to chronic arthritis

- If untreated, arthritis may recur in the same or different joints.

- development of Baker's cyst

Neurological and cognitive manifestations can include:

- meningitis

- meningoencephalitis

- subacute mild encephalopathy, affecting:

- memory

- concentration

- myelitis

- cranial neuropathy

- radiculopathy

- chronic mild axonal polyneuropathy, manifested as:

- distal paresthesia

- radicular pain (less common)

Rarer presentations may include:

- encephalomyelitis

- leukoencephalopathy

- diaphragmatic paralysis caused by phrenic nerve palsy leading to tick-induced respiratory paralysis or respiratory distress

Diagnosis

Early diagnosis and treatment of Lyme disease is necessary to prevent development of more severe and debilitating musculoskeletal and neurological symptoms.

Health professionals should consider a diagnosis of Lyme disease in individuals presenting with suggestive symptoms, particularly if there's a history of tick bite or potential tick exposure.

The diagnosis of early localized Lyme disease is primarily clinical and is made through a combination of:

- history of tick exposure

- clinical signs and symptoms in particular the presence of an erythema migrans rash

- laboratory testing, when appropriate

History of tick exposure

A history of tick exposure includes:

- a recent tick bite or living in or

- having recently visited a Lyme disease risk area

While a known history of tick exposure, particularly to blacklegged or western blacklegged ticks, helps with the diagnosis, absence of a history of exposure does not rule out Lyme disease. Individuals may not recall a tick bite because ticks are tiny and their bites are usually painless. Furthermore, blacklegged ticks and western blacklegged ticks can be found outside currently identified risk areas.

Tick exposure with an erythema migrans rash

Individuals with a known history of tick exposure presenting with an erythema migrans rash may be:

- clinically diagnosed with Lyme disease and

- treated without laboratory confirmation

Tick exposure without an erythema migrans rash

A diagnosis of Lyme disease can't be ruled out in individuals with a known history of tick exposure presenting with other non-specific symptoms, such as headache, fever and muscle and joint pain, but without an erythema migrans rash.

In the absence of an erythema migrans rash, laboratory testing is recommended. An acute and a convalescent sample (2 to 6 weeks after the acute one) are required to obtain laboratory confirmation of Lyme disease.

Treatment shouldn't be delayed in patients with suspected Lyme disease while waiting for confirmation of laboratory tests.

For more information regarding diagnosis and management:

A tick may carry multiple pathogens and transmit them to humans via a single bite. Therefore, while investigating Lyme disease, health professionals should consider infection or co-infection with other tick-borne diseases, such as:

- babesiosis

- anaplasmosis

- Powassan virus

- tick-borne relapsing fever

Consider consultation with an infectious disease specialist when suspecting co-infection.

Treatment

Most cases of Lyme disease can be managed successfully with a timely diagnosis and appropriate treatment. Individuals who are treated with an appropriate antibiotic early in the course of illness (early disease) tend to recover more quickly than those who are treated at later stages of disease (late disease).

Tick exposure with an erythema migrans rash

Individuals with a known history of tick exposure presenting with an erythema migrans rash should be treated promptly for Lyme disease without the need for serological testing.

Tick exposure without an erythema migrans rash

Individuals without an erythema migrans rash may be treated empirically for Lyme disease before laboratory confirmation, depending on the degree of clinical suspicion. This would depend on the individual's symptoms and history of tick exposure.

Persistence of objective findings following treatment, especially high fever, may be due to co-infection with another pathogen transmitted by Ixodes ticks. This calls for investigation for co-infection if the initial antibiotic isn't effective against these pathogens.

For more information regarding treatment:

Lyme disease and pregnancy

Current evidence related to Lyme disease and pregnancy is limited.

While transmission of Lyme disease during pregnancy is possible, the risk of passing Lyme disease to a baby during pregnancy is considered very low.

If a pregnant person has Lyme disease, they can be safely and effectively treated with antibiotics. Early treatment reduces the risk of potential placenta infection and complications.

Learn more about:

Patients with persistent symptoms following treatment of Lyme disease

Most people with early Lyme disease who receive appropriate antibiotics recover completely. However, following treatment, some patients may continue to have persistent symptoms such as fatigue, cognitive difficulties and pain. This may be due to:

- co-infection with another pathogen

- another condition (for example, fibromyalgia, depression, patellofemoral joint disease)

- an autoimmune process which may have been triggered (for example, in the case of knee synovitis of Lyme disease that persists for months after antibiotic therapy)

- permanent tissue damage that may have occurred in patients with previous neurologic involvement

Laboratory testing

Laboratories that employ conventional diagnostic assays and interpretive criteria should be the only laboratories conducting diagnostic testing. Health professionals should send samples to their provincial and territorial laboratories. They will coordinate with the National Microbiology Laboratory, when necessary.

Samples to collect for patients being investigated for Lyme disease include:

- acute serum sample: collected as early as possible after symptom onset

- convalescent serum sample: collected 2 to 6 weeks after the acute sample

Laboratory tests for Lyme disease include:

- screening test for antibodies

- human immunoglobulin combined (IgG and IgM) immunosorbent assay (EIA)

- confirmatory testing

- detection of burgdorferi sensu stricto DNA in tissue, cerebrospinal fluid or synovial fluid by polymerase chain reaction

- a second IgG and IgM combined EIA, different from the screening assay, if following the modified two-tiered testing algorithm

- IgG and/or IgM immunoblots if following the standard two-tiered algorithm

Although the two-tiered serology tests have a high degree of sensitivity, they're not ideal for detecting early or late disseminated infection. Tests may be negative in patients who received early antibiotic treatment. Some individuals who receive treatment during early localized Lyme disease may not seroconvert. That is, IgG antibodies may not be detected in serological tests performed on convalescent samples.

In suspected Lyme disease affecting the central or peripheral nervous system, testing for IgG or IgM antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid may be helpful. Consult your provincial or territorial public health laboratory.

Laboratory accreditation

Laboratory testing should be done through a licensed and accredited public health laboratory.

It's not recommended to:

- perform tests via non-licensed laboratories or private laboratories that don't use U.S. Food and Drug Administration or Health Canada approved tests, nor

- use alternative interpretive criteria

Surveillance

Lyme disease is a nationally notifiable disease. Nationally notifiable diseases are infectious diseases that have been identified collectively by the federal, provincial and territorial governments as priorities for surveillance and control efforts.

The national notification system receives cases reported through provincial and territorial public health authorities. Both confirmed and probable cases of Lyme disease are reportable. The national case definition for Lyme disease is used to classify cases reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Provinces and territories have their own legislation for the reporting of priority infectious diseases. Please consult provincial or territorial public health authority for reporting requirements in your jurisdiction.

For Lyme disease surveillance reports and the Lyme disease risk areas map visit:

Learn more about:

Subscribe to the Zoonoses Bulletin

The Zoonoses Bulletin is an email subscription list that will provide you with regular updates from the Public Health Agency of Canada regarding our work on zoonoses. Zoonoses are infectious diseases that can be spread between animals and people, including those that can be spread through the bite of a tick or mosquito.