Measles: For health professionals

On this page

- Key information

- Epidemiology

- Clinical manifestations

- Risk factors

- Diagnosis and laboratory testing

- Treatment

- Prevention and control

- Surveillance

Key information

Measles is a highly infectious disease caused by the measles (rubeola) virus, a member of the Paramyxoviridae family. It is a nationally notifiable disease, characterized by:

- fever

- cough

- conjunctivitis

- coryza

- a pathognomonic enanthema (Koplik spots)

- a generalized maculopapular erythematous rash that:

- begins on the face

- spreads to the trunk, arms and legs

The virus is spread through the air and by contact with respiratory secretions from the nose and mouth. It can be prevented with vaccination.

Epidemiology

Humans are the only known reservoir for measles.

Incubation period

The incubation period is about 10 days from exposure to the onset of prodromal symptoms (ranging from 7 to 18 days). The interval from exposure to appearance of rash averages 14 days, but the rash can appear as late as 21 days.

Transmission

Measles is one of the most highly communicable infectious diseases with greater than a 90% secondary attack rate among people who are susceptible.

Measles spreads through the air via inhalation of infectious respiratory particles (i.e., airborne transmission) and direct contact with infectious nasal or throat secretions onto mucous membranes. Less commonly, measles can also spread through direct contact with contaminated surfaces or objects (i.e., transfer of infectious particles from a fomite onto mucous membranes via unclean hands).

The measles virus can persist in the air for up to 2 hours after a person who is infected has left the space. Infectious measles particles may also remain viable on surfaces for a short period of time.

Airborne precautions should be used for patients with confirmed or suspected measles in health care settings.

People with confirmed measles are infectious from 4 days before rash onset to 4 days after the appearance of the rash (with the first day of rash being day zero). People who do not develop a rash are considered infectious for 10 days after first symptom onset. Those who are immunocompromised may have prolonged excretion of the virus in respiratory tract secretions; and may remain contagious for the entire duration of their illness. People who recover from measles have lifelong immunity to the disease.

Learn more:

- Notice: Updated infection prevention and control recommendations for measles in healthcare settings

- Routine practices and additional precautions for preventing the transmission of infection in healthcare settings

Clinical manifestations

Prodromal symptoms of measles begin 7 to 21 days after exposure and include:

- fever

- malaise

- cough

- coryza

- conjunctivitis

A pathognomonic enanthema (white spots on the buccal mucosa, known as Koplik spots) may appear 2 to 3 days after symptoms begin.

Measles is characterized by a generalized maculopapular rash, which usually appears about 14 days after infection, or about 3 to 7 days after prodromal symptoms begin. It typically begins on the face, advances to the trunk of the body and then to the arms and legs. The rash lasts 4 to 7 days.

Atypical presentation of measles can be seen in people with breakthrough infections or those who are immunocompromised. For those:

- with a breakthrough infection, individuals may present with modified measles, which is generally milder (i.e., less fever, cough, coryza or conjunctivitis)

- who are immunocompromised, individuals often have more severe disease and may also present without a rash or with an atypical rash

An individual is considered to have a breakthrough infection if they test positive for measles and have a history of vaccination at least 14 days prior (can include one or more doses of a measles-containing vaccine) or have previous serological evidence of immunity.

Complications

Complications are more likely in:

- infants and children under 5 years of age

- people who are immunocompromised

- people who are pregnant

Common complications from measles can include:

- otitis media (1 of every 10 cases)

- bronchopneumonia (1 of every 10 cases)

- diarrhea (less than 1 of every 10 cases)

Severe complications of measles can include:

- respiratory failure

- encephalitis

- occurs in approximately 1 of every 1,000 reported cases

- may result in permanent neurologic sequelae

- death

- estimated to occur in 1 to 10 of every 10,000 cases of measles in higher-income countries like Canada (Measles vaccines: WHO position paper, April 2017)

- mainly due to a respiratory or neurologic complication

Long-term sequelae of measles can include:

- blindness

- deafness

- permanent neurological sequelae

- subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE)

SSPE is a rare and fatal degenerative central nervous system disease. It is characterized by:

- behavioural and intellectual deterioration

- seizures

These changes can occur several years after infection with the measles virus.

SSPE occurs at a rate of approximately 4 to 11 in every 100,000 measles cases, and the risk of SSPE increases in infected individuals under 5 years of age to 18 per 100,000 cases. The highest rates of SSPE occur in children infected before 2 years of age.

Measles during pregnancy can lead to complications in the birthing parent, including:

- pneumonia

- hepatitis

- death

Measles infection during pregnancy can also result in:

- low birth weight

- premature labour

- spontaneous abortion

- congenital measles

- this rare but severe form of measles can result in pneumonia, encephalitis and death in an infected infant

Measles infection can also produce immune amnesia, which is the temporary loss of immunity to other previously seen pathogens after an acute measles infection. While someone who was recently ill with measles is well-protected from future measles infections, they may be less protected from other infections than they were before having measles. Immune amnesia is not seen in those who received the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine. In addition to the possibility of longer-term loss of immunity, measles infection is known to cause a more immediate immunosuppression that makes the individual with measles susceptible to other pathogens.

Images of clinical manifestations of measles

The following images show the typical watery conjunctivitis and the red blotchy appearance of a measles rash. The rash usually starts on the face, then progresses to the trunk, arms and legs.

The measles rash appears macular or maculopapular (fine, flat or slightly raised). It becomes confluent as it progresses, giving it a red, blotchy appearance at its peak. In mild cases, the rash tends not to be confluent. However, in severe cases, the rash is more confluent, and the skin may be completely covered.

A slight desquamation or peeling of the skin occurs as the rash clears, which can be more pronounced on darker skin tones.

Courtesy of Dr. CW Leung, Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Princess Margaret Hospital, Hong Kong.

Image 1 on the left shows a generalized maculopapular rash on the chest and abdomen of a child.

Courtesy of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Image 2 on the right shows desquamation of the skin as the rash clears, which can be more pronounced on darker skin tones.

Courtesy of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Image 3 on the left shows a child in the later stages of measles rash and the watery eyes due to conjunctivitis.

Courtesy of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Image 4 on the right shows the white Koplik spots found classically in the buccal mucosa of the inner mouth.

Risk factors

All persons who have not had a previous measles infection or who have not been vaccinated with a measles-containing vaccine are at risk of measles infection. However, some protection can be provided to young babies as a result of antibody transfer during pregnancy.

In Canada, adults born before 1970 are generally presumed to have acquired immunity due to infection with measles when they were younger. This is due to high levels of measles circulation before 1970. However, vaccination for measles is still recommended for some population groups, even if born before 1970.

The measles chapter in the Canadian Immunization Guide provides:

- guidance on people who may be considered susceptible or immune to measles

- subsequent recommendations on need for a measles-containing vaccine

- vaccination of specific populations

This includes specific recommendations for outbreak control and for individuals who:

- are health care providers

- are members of the military

- are planning travel outside of Canada

- are new to Canada

- are in post-secondary educational settings

- are pregnant or breastfeeding

- have chronic disease

- are immunocompromised

- have inadequate immunization records

- are in healthcare institutions

These individuals may be more likely to be exposed to measles and could spread measles to large numbers of individuals should they become infected.

Infection is most likely to occur in people who are non-immune travelling to countries or regions where measles is circulating. Occasionally, a returning traveller who is infected with measles can spread infection in Canada. This can be a particular problem if spread occurs in a community where many people are unvaccinated or not fully vaccinated.

Learn more:

Diagnosis and laboratory testing

Health care providers should suspect measles in a patient presenting with a:

- febrile illness and rash

- history suggesting that they are not immune to measles, particularly if they:

- have travelled

- are known to have had an epidemiologic link to a measles case or outbreak

Other clinical manifestations, such as the prodrome followed by the rash and the progression of the rash, raise clinical suspicion for measles.

Health care providers are required to report suspected measles cases to their local public health authority for more direction. Do not wait for laboratory results to be reported.

When measles is suspected, specimens should be collected as soon as possible in order to diagnose measles and are essential for maintaining adequate viral surveillance. These include:

- a nasopharyngeal or throat swab for viral detection (polymerase chain reaction [PCR] test)

- urine for viral detection (PCR)

- blood for serology

Collection of specimens for viral detection (RT-PCR) is recommended in all cases. In addition to confirming the diagnosis in suspect cases, viral detection is used:

- for genotyping, which can help determine the source of infection

- to support surveillance that is necessary to monitor measles elimination status

Immunoglobulin M (IgM) for measles can be falsely negative if taken less than 3 days after onset of the rash. In addition, the positive predictive value of IgM testing is reduced due to the low prevalence of measles in the community.

Serological testing may be indicated to confirm the diagnosis of measles or to determine immune status. Serological testing is not recommended to check:

- susceptibility before measles vaccination

- response after receiving measles vaccination

Learn more:

Treatment

There is no specific antiviral treatment for measles infection. Medical management is supportive and aimed at symptom relief and management of complications. This can include rehydration and management of secondary complications of measles, such as bacterial infections.

As vitamin A deficiency is linked to delayed recovery and greater complications with measles, and because measles may precipitate a vitamin A deficiency, health care providers should consider giving vitamin A. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends children diagnosed with measles be given 2 doses of vitamin A supplements. Dosing information can be found in the WHO position paper.

Learn more:

Prevention and control

Measles can be prevented with vaccination. The measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine or the measles-mumps-rubella-varicella (MMRV) vaccine are routinely given in childhood.

The first dose is recommended after the first birthday at 12 to 15 months of age. A second dose is given at either 18 months of age or any time thereafter, but no later than school entry. Two doses provide lifelong immunity in most people.

The MMR vaccine can be given throughout the lifespan in people that have not received all their scheduled vaccinations. The MMRV vaccine is authorized for individuals 12 months to less than 13 years of age.

Learn more:

Adverse events and contraindications

Adverse events following immunization with a measles-containing vaccine are usually mild and resolve on their own, including local injection site reactions that occur soon after vaccination. Some side effects may develop 1 to 3 weeks after vaccination, including fever and a mild rash.

Less common, serious adverse events post vaccination can occur.

There are circumstances where measles vaccination may be contraindicated.

Learn more:

Outbreak control and post-exposure prophylaxis

Health care providers should contact their local public health authority for more direction when a measles case is suspected. Confirmed cases are nationally notifiable. Persons infected with measles should isolate for 4 days after the appearance of the rash to prevent transmission to others. Individuals who do not develop a rash should isolate for 10 days, with day 1 being the first day of symptom onset.

In health care settings, airborne precautions should be followed, including the use of an airborne infection isolation room (AIIR). Only healthcare workers with presumptive immunity should enter the room of a patient with suspected or confirmed measles. A fit-tested N95 (or an equivalent, or higher protection) respirator is recommended when caring for patients with suspected or confirmed measles, regardless of the immunity/vaccination status of the healthcare worker.

All contacts of a person who may be infected with measles should be identified and assessed for expected immunity. Contacts who do not meet the criteria for expected immunity should be managed as per the Guidance for the public health management of measles cases, contacts and outbreaks in Canada.

The MMR vaccine or immunoglobulin (Ig) may be used for measles post-exposure management in persons who are susceptible depending on the time since exposure and the age or health criteria of the individual who was exposed. Ig provides only short-term protection and requires postponing the administration of MMR vaccine. Long-term protection against measles only follows immunization with MMR or MMRV vaccine, or infection with the measles virus.

Despite the use of MMR vaccine or Ig for post-exposure management, measles infection may occur. Individuals who have been exposed should be counseled regarding:

- signs and symptoms of measles

- how to properly quarantine or isolate

- when to seek medical care, including calling ahead to health care providers to advise them of the possibility of measles before going to a health care setting so that appropriate infection control precautions can be taken

Additionally, during an outbreak, efforts should be made to encourage people to stay up to date with their vaccinations. In an outbreak situation, MMR vaccine may be given as early as 6 months of age. If given between 6 months and less than 12 months of age, 2 additional doses of measles-containing vaccine must be administered after the child is 12 months old to ensure long lasting immunity to measles.

Learn more:

- Process for contact management for measles cases communicable during air travel

- Guidance for the public health management of measles cases, contacts and outbreaks in Canada

- Notice: Updated infection prevention and control recommendations for measles in healthcare settings

- Updated recommendations on measles post-exposure prophylaxis: National Advisory Committee on Immunization

- Routine practices and additional precautions for preventing the transmission of infection in healthcare settings: Airborne precautions

Surveillance

Measles is a nationally notifiable disease in Canada and measles surveillance is conducted by public health professionals in provinces and territories. Cases meeting the national case definition are reported by health care providers to their local public health authority. Information is subsequently forwarded to provincial or territorial public health officials and then to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC).

National enhanced surveillance of measles is conducted through the Canadian Measles and Rubella Surveillance System (CMRSS). CMRSS is coordinated by PHAC. This system involves weekly collection of enhanced measles data from all provinces and territories, including reporting if there are no cases. This allows for timely surveillance of measles elimination in Canada.

Genotype surveillance is conducted by PHAC's National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) and is included in CMRSS. The NML is a World Health Organization and Pan-American Health Organization accredited measles and rubella regional reference laboratory. Genotyping is an important tool in measles surveillance for 2 key reasons.

- It allows for the differentiation between chains of measles transmission, which:

- is necessary to monitor elimination status

- can help to determine the source of an infection

- It is the only way to distinguish if symptoms are due to recent vaccination or a wild-type measles virus infection.

Weekly summaries of surveillance information collected through CMRSS on measles cases and activity in Canada are provided in the Measles and Rubella Weekly Monitoring Report.

Provinces and territories also submit information on measles cases annually to the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System.

Learn more:

- Notifiable Diseases Online

- National case definition: Measles

- National Microbiology Laboratory

- Canadian Measles and Rubella Surveillance System

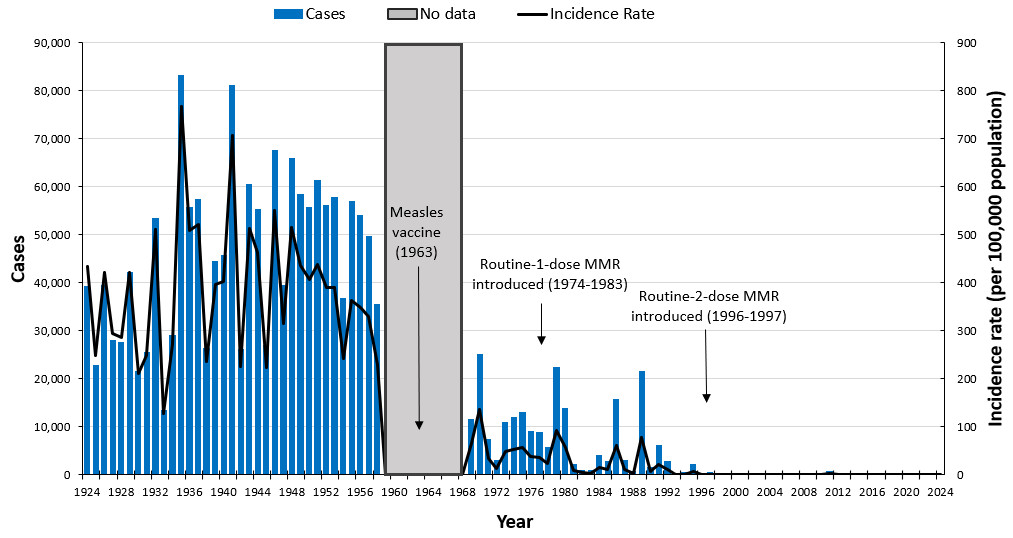

History of measles in Canada

Measles has been nationally notifiable since 1924 with the exception of 1959 to 1968. Before vaccinations, about 10,000 to 90,000 people living in Canada were infected with measles every year.

In 1963, a live-attenuated vaccine was approved for use in Canada, followed by the approval of an inactivated vaccine in 1964. The inactivated vaccine had limited availability, and its use was discontinued by the end of 1970.

A single-dose schedule with the live-attenuated vaccine was introduced into all provincial and territorial routine immunization programs by the early 1970s. The routine 1-dose MMR combination vaccine was introduced between 1974 and 1983. The routine 2-dose MMR vaccine was implemented nationally in 1996 to 1997.

In 1996 to 1997, catch-up campaigns were provided to school-aged children to offer them a second dose of a measles-containing vaccine. Since the introduction of the measles vaccine in Canada, measles cases have decreased by more than 99% (Figure 1). Surveillance was interrupted from 1959 to 1968 as per the blue shading.

Figure 1: Text description

| Year | Cases | Incidence rate (cases per 100,000 population) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1924 | 39,216 | 433.6 | |

| 1925 | 22,777 | 247.7 | |

| 1926 | 39,429 | 421.6 | |

| 1927 | 28,150 | 295.2 | |

| 1928 | 27,733 | 284.9 | |

| 1929 | 42,132 | 420.7 | |

| 1930 | 21,606 | 211.9 | |

| 1931 | 25,664 | 247.7 | |

| 1932 | 53,508 | 509.8 | |

| 1933 | 13,471 | 126.9 | |

| 1934 | 29,115 | 271.4 | |

| 1935 | 83,127 | 767.6 | |

| 1936 | 55,724 | 509.6 | |

| 1937 | 57,408 | 520.5 | |

| 1938 | 26,328 | 236.4 | |

| 1939 | 44,476 | 395.3 | |

| 1940 | 45,851 | 403.5 | |

| 1941 | 81,051 | 705.4 | |

| 1942 | 26,258 | 225.6 | |

| 1943 | 60,485 | 513.5 | |

| 1944 | 55,317 | 463.7 | |

| 1945 | 26,978 | 223.8 | |

| 1946 | 67,528 | 550.4 | |

| 1947 | 39,455 | 315.0 | |

| 1948 | 66,004 | 515.7 | |

| 1949 | 58,511 | 435.9 | |

| 1950 | 55,653 | 406.6 | |

| 1951 | 61,370 | 438.8 | |

| 1952 | 56,178 | 389.2 | |

| 1953 | 57,871 | 390.5 | |

| 1954 | 36,850 | 241.5 | |

| 1955 | 56,922 | 363.3 | |

| 1956 | 53,986 | 348.1 | |

| 1957 | 49,712 | 330.3 | |

| 1958 | 35,531 | 229.3 | |

| 1959 | No data | No data | |

| 1960 | No data | No data | |

| 1961 | No data | No data | |

| 1962 | No data | No data | |

| 1963 | No data | No data | Measles vaccine |

| 1964 | No data | No data | |

| 1965 | No data | No data | |

| 1966 | No data | No data | |

| 1967 | No data | No data | |

| 1968 | No data | No data | |

| 1969 | 11,720 | 64.4 | |

| 1970 | 25,137 | 136.4 | |

| 1971 | 7,439 | 33.8 | |

| 1972 | 3,136 | 14.1 | |

| 1973 | 10,911 | 48.3 | |

| 1974 | 11,985 | 52.3 | Routine-1-dose MMR introduced |

| 1975 | 13,143 | 56.6 | |

| 1976 | 9,158 | 38.9 | |

| 1977 | 8,832 | 37.1 | |

| 1978 | 5,858 | 24.4 | |

| 1979 | 22,444 | 92.4 | |

| 1980 | 13,864 | 56.3 | |

| 1981 | 2,307 | 9.3 | |

| 1982 | 1,064 | 4.2 | |

| 1983 | 934 | 3.7 | |

| 1984 | 4,086 | 15.9 | |

| 1985 | 2,899 | 11.2 | |

| 1986 | 15,796 | 60.3 | |

| 1987 | 3,065 | 11.5 | |

| 1988 | 710 | 2.6 | |

| 1989 | 21,523 | 78.5 | |

| 1990 | 1,738 | 6.3 | |

| 1991 | 6,151 | 21.9 | |

| 1992 | 2,915 | 10.2 | |

| 1993 | 192 | 0.7 | |

| 1994 | 517 | 1.8 | |

| 1995 | 2,366 | 8.0 | |

| 1996 | 328 | 1.1 | Routine-2-dose MMR introduced |

| 1997 | 531 | 1.8 | |

| 1998 | 17 | 0.1 | |

| 1999 | 32 | 0.1 | |

| 2000 | 207 | 0.7 | |

| 2001 | 38 | 0.1 | |

| 2002 | 9 | <0.1 | |

| 2003 | 17 | 0.1 | |

| 2004 | 9 | <0.1 | |

| 2005 | 8 | <0.1 | |

| 2006 | 13 | <0.1 | |

| 2007 | 101 | 0.3 | |

| 2008 | 61 | 0.2 | |

| 2009 | 14 | <0.1 | |

| 2010 | 99 | 0.3 | |

| 2011 | 752 | 2.2 | |

| 2012 | 10 | <0.1 | |

| 2013 | 83 | 0.2 | |

| 2014 | 418 | 1.2 | |

| 2015 | 196 | 0.5 | |

| 2016 | 11 | <0.1 | |

| 2017 | 45 | 0.1 | |

| 2018 | 29 | 0.1 | |

| 2019 | 113 | 0.3 | |

| 2020 | 1 | <0.1 | |

| 2021 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2022 | 3 | <0.1 | |

| 2023 | 12 | 0.1 | |

| 2024 | 147 | 0.4 |

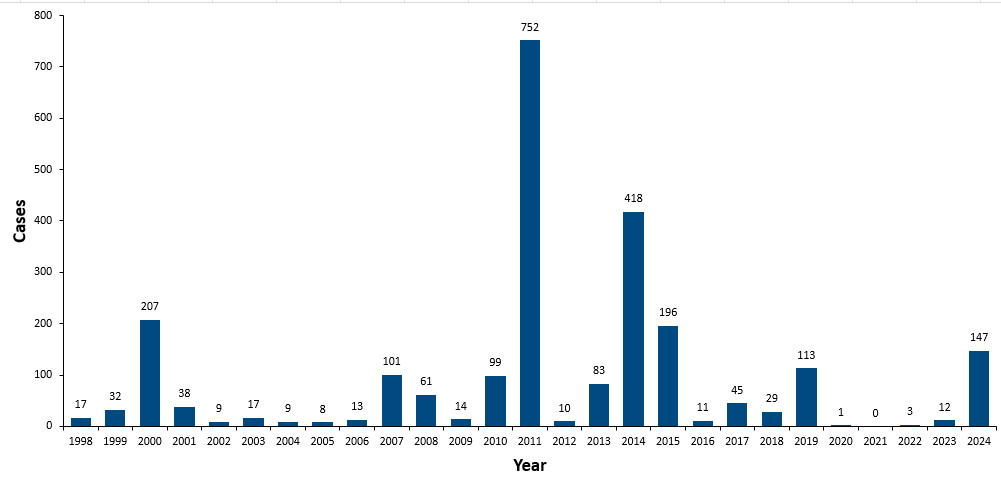

In 1998, Canada achieved elimination status for measles as a direct result of successful routine vaccination programs. This meant that endemic transmission no longer takes place, and most cases and outbreaks arise from outside of Canada with limited spread in Canada. Canada continued to demonstrate low measles activity to 2024 (Figure 2).

In 2025, large measles outbreaks have occurred across Canada, primarily affecting unvaccinated individuals. Current measles activity in Canada is updated on a weekly basis in the Measles and rubella weekly monitoring reports.

Figure 2: Text description

| Year | Cases |

|---|---|

| 1998 | 17 |

| 1999 | 32 |

| 2000 | 207 |

| 2001 | 38 |

| 2002 | 9 |

| 2003 | 17 |

| 2004 | 9 |

| 2005 | 8 |

| 2006 | 13 |

| 2007 | 101 |

| 2008 | 61 |

| 2009 | 14 |

| 2010 | 99 |

| 2011 | 752 |

| 2012 | 10 |

| 2013 | 83 |

| 2014 | 418 |

| 2015 | 196 |

| 2016 | 11 |

| 2017 | 45 |

| 2018 | 29 |

| 2019 | 113 |

| 2020 | 1 |

| 2021 | 0 |

| 2022 | 3 |

| 2023 | 12 |

| 2024 | 147 |

Learn more:

- Measles and rubella weekly monitoring reports

- Provincial and territorial routine and catch-up vaccination schedule for infants and children in Canada

Why measles outbreaks can happen in Canada

While measles in Canada is no longer considered endemic, outbreaks can happen when a person who is unvaccinated or non-immune travels to an area where measles is circulating and becomes infected with measles and is infectious to others when they return. The risk of measles spreading is highest when there are a lot of unvaccinated or non-immune people clustered together in particular regions or communities. Vaccination rates in Canada, while high, are currently below the threshold for community immunity in some places.

Importation and local transmission can, and has, led to measles outbreaks in Canada.

The vaccination coverage goal of 95% has been established for all recommended childhood vaccines by 2 and 7 years of age based on:

- the National Immunization Strategy

- vaccination coverage goals and vaccine preventable disease reduction targets by 2025

This is especially important for measles-containing vaccines.

Related links

Publications

- Measles surveillance in Canada: 2019

- Immunization, vaccines and biologicals: Measles (World Health Organization)

- Vaccine Preventable Disease: Surveillance Report to December 31, 2019: Measles

Guidelines and recommendations

- Measles vaccines: Canadian Immunization Guide

- National Advisory Committee on Immunization: Statements on measles vaccines

- Process for contact management for measles cases communicable during air travel