The Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention – Progress Report 2020

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 1,131 KB, 68 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: 2020

Cat.: HP32-10e-E-PDF

ISBN: 2562-377X

Pub.: 200077

Related topics

Table of contents

- Introduction

- The changing landscape and current environment

- Facts about suicide in Canada

- Update on federal activities

- Going forward

Note to readers:

Reading about suicide may bring about difficult emotions.

If you or someone you know is in immediate danger, please call 9-1-1.

Help is available 24/7 for suicide crisis and prevention. Here are some resources:

- Canada Suicide Prevention Service: 1-833-456-4566 or text 45645 (evenings)

- Kids Help Phone: 1-800-668-6868 or text CONNECT to 686868 (youth) or 741741 (adults)

- Hope for Wellness Help Line: 1-855-242-3310

- Trans Lifeline: 1-877-330-6366

- For Quebec residents: 1-866-APPELLE (277-3553)

Additional resources :

https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/suicide-prevention/warning-signs.html

Minister's message

I am pleased to share the 2020 Progress Report on the Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention.

Suicide is a leading cause of death in Canada – a serious public health issue that affects people of all ages and backgrounds. Approximately 4,000 people die by suicide in Canada each year. Suicide has a profound impact on individuals, families and entire communities. That is why preventing suicide is an important priority for the Government of Canada. As we respond to the COVID-19 pandemic and its wider consequences, it will be important to track and mitigate the impact of the pandemic on the mental health and wellbeing of Canadians, including suicide risk.

The Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention (the Framework) provides a foundation for aligning federal activities and complementing the important work underway across Canada, within Indigenous communities, among provinces and territories and national organizations working in suicide prevention. It focuses on reducing stigma and raising awareness, connecting people, information, and resources, and advancing knowledge and evidence to better understand suicide and inform prevention, treatment, and recovery. This year's Progress Report focuses on suicide prevention and life promotion activities led by key federal departments and partners from 2018 to 2020.

While we have made progress over the past two years in advancing our federal mental health and suicide prevention initiatives, there is more to do. Going forward we will implement a National Suicide Prevention Action Plan in the areas of suicide-related research and data, responsible reporting, best practices and training, and tailored programs for populations most affected by suicide.

As Minister of Health, I recognize that addressing suicide requires commitment and coordination across a variety of sectors, levels of government and within diverse communities. That is why we will continue to work with our partners and people with lived experiences to research and share the most up-to-date information and resources about suicide prevention.

I am optimistic that through our collective efforts, we will make important progress in preventing suicide and improving the circumstances that empower people in Canada to live their lives with dignity, hope, healing, recovery and resiliency.

The Honourable Patty Hajdu

Minister of Health

Executive summary

The 2020 Progress Report on the Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention provides an update on federal activities related to suicide prevention between 2018 and 2020.

The report highlights the changing context for suicide prevention in Canada. Since the release of the Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention (Framework) in 2016, our understanding of suicide and its prevention, and the broader mental health landscape, has continued to evolve. In particular, two key developments have emerged since the publication of the 2018 Progress Report: Parliament's unanimous adoption of Motion 174 – A National Suicide Prevention Action Plan (Action Plan), and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. This report profiles federal initiatives and investments that address the direct and indirect impacts of the pandemic on the mental health of Canadians.

An overview of suicide data is provided in the section “Facts about Suicide in Canada”. In 2018, 3,811 people died by suicide, corresponding to a suicide mortality rate of 10.3 per 100,000 population. While suicide mortality rates have remained stable since 2008, the potential negative impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and related public health measures on the suicide rate remains unknown.

Aligned with the Framework's strategic objectives, the report highlights federal initiatives in suicide prevention which aim to:

- Promote holistic and strengths-based approaches focused on wellness - such as the National Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy, The First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework and programs supporting wellness and life promotion;

- Reduce stigma and raise public awareness – through the development of evidence-based resources, including updated media guidelines (Mindset), the adaptation of PHAC's bilingual “Language Matters” resource, and suicide prevention awareness for rail lines;

- Connect Canadians, information and resources – such as support for a pan-Canadian suicide prevention service, Indigenous-led suicide prevention and life promotion efforts, and suicide prevention resources for Veterans, public safety officers, and members of the Canadian Armed Forces; and,

- Accelerate the dissemination of research and innovation in suicide prevention – including the Mental Health Commission of Canada's work on the Roots of Hope Research Demonstration Project which builds upon community expertise to implement suicide prevention interventions that are tailored to the local context; and, PHAC's collaboration with an artificial intelligence (AI) company on a feasibility study that examines the use of AI and machine learning to detect suicide ideation using retrospective Twitter data.

I. Introduction

The Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention Act (Act) became legislation in 2012, requiring the Government of Canada to work with relevant departments, partners, provinces, and territories on the development of the Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention (Framework). Published in 2016, the Framework sets out the Government of Canada's guiding principles and strategic objectives for suicide prevention.

The Act requires the Government of Canada to report on activities and progress related to the Framework every two years. The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) is responsible for publishing the progress reports on behalf of relevant federal departments and agencies contributing to suicide prevention. The previous progress report highlighted activities from 2016 to 2018.

The Framework is not a strategy nor does it replace existing strategies or frameworks implemented by provinces, territories, communities or Indigenous organizations. The Framework sets out the federal role for aligning suicide prevention efforts, and biennial reporting enables the sharing of information to enhance coordination and collaboration, complementing the important work underway by others in the sector. A summary of the Framework follows in Figure 1.

The present report provides an update on federally funded suicide prevention initiatives, noting that it does not capture all of the suicide prevention and life promotion initiatives taking place in Canada. The report includes distinctions-based approaches to mental wellness and suicide prevention among First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples. Distinctions-based programs acknowledge the unique histories, cultures and realities of First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities in order to best meet their respective needs.

Figure 1. The Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention (2016): At a glance

| Vision | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A Canada where suicide is prevented and everyone lives with hope and resilience | ||||

| Mission | ||||

| Prevent suicide in Canada, through partnership, collaboration, and innovation while respecting the diversity of cultures and communities that are touched by this issue | ||||

| Purpose | ||||

| To guide the federal government's efforts in suicide prevention through implementation of An Act respecting a Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention (2012) | ||||

| Strategic objectives | ||||

|

|

|

||

| Legislated elements (Section 2 of the Act) | ||||

| 1. Provide guidelines to improve public awareness and knowledge of suicide | 2. Disseminate information about suicide and its prevention.

3. Make existing statistics about suicide and related risk factors publicly available. 4. Promote collaboration and knowledge exchange across domains, sectors, regions, and jurisdictions. |

5. Define best practices for suicide prevention. 6. Promote the use of research and evidence-based practices for suicide prevention. |

||

| Guiding principles | ||||

|

||||

| Foundation | ||||

| Changing Directions, Changing Lives: A Mental Health Strategy for Canada | ||||

II. The changing landscape and current environment

In 2016, the Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention (Framework) highlighted the complexity of preventing suicide. While there is no single cause that explains or predicts suicide, a combination of factors are associated with suicide, such as mental illness, physical health, personal issues and loss, childhood abuse and neglect, exposure to trauma (e.g., personal, occupational and intergenerational), family history of suicide, prior suicide attempt, misuse of alcohol and other substances, and access to lethal means. As a result, effective suicide prevention requires a multifaceted, comprehensive approachFootnote 1 that includes evidence-based strategies at the community and individual level, tailored to respond to the needs and contexts of populations that experience unique risk factors.

Since the release of the Framework, our understanding of suicide and its prevention, as well as the broader mental health landscape, continues to evolve. This year's report reflects the changing landscape by highlighting a broad range of activities that contribute to suicide prevention, including holistic and strengths-based approaches focused on wellness.

Two key developments since the publication of the 2018 Progress Report are Parliament's unanimous adoption of Motion 174 – a National Suicide Prevention Action Plan, and the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, including wider consequences of related public health measures.

While the landscape and social environments will continue to change, advancing suicide prevention in Canada will remain contingent on continuous coordination and collaboration between federal departments and agencies, with partners, stakeholders and people with lived experiences. Working together, with a concerted focus on a National Suicide Prevention Action Plan, we will continue to advance suicide prevention in key areas for people most affected.

National Suicide Prevention Action Plan (M-174)

On May 8, 2019, Parliamentarians voted unanimously in favour of Motion 174 (M-174), which calls for a national suicide prevention action plan (Action Plan). M-174 is non-binding, and there were no new resources attached to the Action Plan (see Appendix A). The Action Plan is the latest in a series of key suicide prevention policy developments in Canada. A summary of these developments is provided in Appendix B.

The Government of Canada is supporting the development of the Action Plan while emphasizing current federal initiatives in suicide prevention, underlining the importance of Indigenous-led initiatives for addressing suicide in First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities, and acknowledging provincial and territorial jurisdiction in some areas. Through its convening role on the Framework, PHAC will continue to facilitate coordination and collaboration with relevant departments and agencies, and partners to develop the Action Plan.

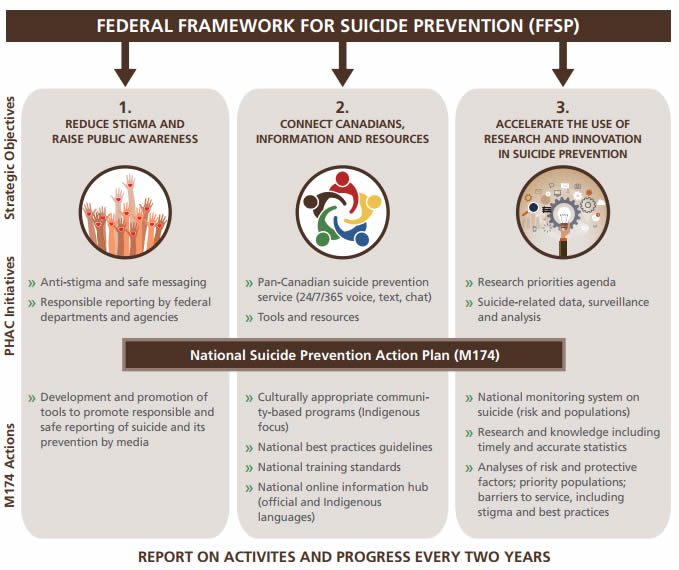

Many of the items proposed for the Action Plan align with existing federal initiatives under the objectives of the legislated Framework. Figure 2 presents a diagram depicting this alignment.

Figure 2 - Text description

The figure illustrates the alignment between the three strategic objectives of the Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention (FFSP) and the items outlined in the National Suicide Prevention Action Plan (Motion-174). This diagram works from left to right as well as from top to bottom, showing how the FFSP encompasses the actions of the National Suicide Prevention Action Plan.

The first strategic objective is to Reduce Stigma and Raise Public Awareness. PHAC initiatives under this objective are:

- Anti-stigma and safe messaging

- Responsible reporting by federal departments and agencies

National Suicide Prevention Action Plan items that align with this objective are:

- Development and promotion of tools to promote responsible and safe reporting of suicide and its prevention by media

The second strategic objective of the FFSP is to Connect Canadians, Information, and Resources. PHAC initiatives under this objective are:

- Pan-Canadian suicide prevention service (24/7/365 voice, text, chat)

- Tools and resources

National Suicide Prevention Action Plan items that align with this objective are:

- Culturally appropriate community-based programs (Indigenous focus)

- National best practices guidelines

- National training standards

- National online information hub (official and Indigenous languages)

The third strategic objective of the FFSP is to Accelerate the Use of Research and Innovation in Suicide Prevention. PHAC initiatives under this objective are:

- Research priorities agenda

- Suicide-related data, surveillance and analysis

National Suicide Prevention Action Plan items that align with this objective are:

- National monitoring system on suicide (risk and populations)

- Research and knowledge including timely and accurate statistics

- Analyses of risk and protective factors; priority populations; barriers to service, including stigma and best practices

PHAC will report on activities and progress every two years.

COVID-19 pandemic

On March 11, 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced the COVID-19 outbreak as a global pandemic. While necessary public health measures such as physical distancing have been implemented to reduce transmission, there are concerns about their negative impact on the mental health of Canadians and the potential for increased rates of suicide. Wider consequences of the pandemic include impacts at the societal or community level (e.g., economic downturn, barriers to accessing health care, including mental health care) and impacts at the relationship or individual level (e.g. job/financial loss, harmful use of alcohol/substances, family violence, social isolation, and experiences of trauma), all of which are risk factors for suicideFootnote 2,Footnote 3,Footnote 4.

The mental health of Canadians has declined during the COVID-19 pandemic. The percentage of Canadians (aged 15+) who reported that their mental health is very good or excellent was only 54% in the first cycle of the Canadian Perspective Survey Series (CPSS; March 29-April 3, 2020),Footnote 5 and continued to decrease to 48%Footnote 6 in the second cycle (May 4-10, 2020), compared to 68% in 2018. Furthermore, data from these surveys suggest that the COVID-19 pandemic has had a larger negative impact on the mental health of some socio-demographic groups (e.g., young, women, Indigenous people, etc.)Footnote 6,Footnote 7,Footnote 8,Footnote 9,Footnote 10.

Supplementary information: COVID-19 survey containing information on suicide

The mental health surveys conducted by the Canadian Mental Health Association and the University of British Columbia (MayFootnote 11 and September Footnote 12 2020) reported that one in ten Canadians (10%)Footnote 12 experienced thoughts of suicide since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Comparatively, 3% of Canadians reported thoughts of suicide in 2019.Footnote 13 Moreover, the surveys also found that thoughts or feelings of suicide were more common for certain groups, e.g., LGBTQ2+ (28%),Footnote 12 people with existing mental health issues (27%)Footnote 12 or disabilities (24%),Footnote 12 Indigenous people (20%),Footnote 12 people with low income (14%),Footnote 11 and parents with young children living at home (13%).Footnote 12

While there are no clear signs of increased suicide deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic, there are some concerning signs of an impact on suicidality, such as through an increase in calls to distress centres. For example, the Canada Suicide Prevention Service has experienced a significant increase in calls since the start of the pandemic, with the number of interactions rising from 2,375 in March 2020 to 6,700 in October 2020.

There is a possibility of a delayed effect similar to one that has been documented after disasters. For example, immediately following the earthquake in Japan in 2011, the rate of suicide among men remained low, however, the suicide rate among men increased significantly two years following the earthquake.Footnote 14 Evidence suggests that the risks associated with the pandemic may be alleviated through improved access to supports.Footnote 15

This shows the importance of continued monitoring during and following the pandemic. To this end, PHAC and Statistics Canada are partnering to conduct the following surveys:

- The Survey on COVID-19 and Mental Health (SCMH), which includes questions on mental health and thoughts of suicide. The initial findings from this large representative sample will be published in February 2021, and the survey will be repeated from February to April 2021.

- The Survey on Mental Health and Stressful Events, which includes questions regarding suicidal thoughts and general mental health.

Further examples of data collection and research related to the mental health impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are described in Appendix C.

In addition, The Chief Public Health Officer of Canada's Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2020 – From Risk to Resilience: An Equity Approach to COVID-19 describes the cumulative impact of COVID-19 and public health measures on Canadian society including on mental health with a particular focus on equity considerations.

Federally-funded resources related to mental health and substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic

As part of its response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government of Canada has supported a number of investments to address direct and indirect impacts of the pandemic. Examples of investments related to mental health and substance use include:

Wellness Together Canada portal

The Government of Canada is supporting the Wellness Together Canada portal, which provides Canadians in all provinces and territories with free access to a range of credible resources and supports related to mental health and substance use. The portal complements suicide prevention services by providing access to educational content, self-guided programming, peer-to-peer support, and confidential one-to-one counselling and crisis text lines. The Government is planning an independent evaluation of the portal to examine how it has addressed key objectives, such as increasing access to services and improving client outcomes.

The November 2020 Fall Economic Update announced an additional $43 million to provide further support for the Wellness Together Canada portal and the resources it offers. To date, the Government of Canada has invested $67 million in Wellness Together Canada.

Supporting increased demand for services

The Government of Canada has also invested $7.5 million to support Kids Help Phone (KHP) in providing mental health support for youth during the COVID-19 pandemic. KHP has experienced a significant increase in demand for its services as a result of the mental health impact of the pandemic, with suicide among the top five reasons youth sought support between April and September 2020. By the end of 2020, KHP projects they will reach at least 3 million young people, compared to 1.9 million youth in 2019.

In addition, the November 2020 Fall Economic Update announced a $50 million investment to bolster the capacity of distress centres, which are experiencing a surge in demand during the COVID-19 pandemic.

COVID-19 readiness resource for public safety personnel

The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the essential role of public safety personnel (PSP)Footnote 16 and other frontline workers in serving and protecting all Canadians. As a result, in March 2020, with funds from Public Safety Canada and significant in-kind contributions from Veterans Affairs Canada, the Canadian Institute for Public Safety Research and Treatment designated a COVID-19 Task Force to create an online resource. The COVID-19 Readiness Resource Project (CRRP), supports the mental health and well-being of Canadian first responders, including PSP, working on the frontlines of the pandemic. The CRRP Final Report outlines the resources and content available to all PSP across Canada.

Interim Federal Health Program

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) recognizes that refugees, asylum claimants, and other vulnerable newcomers, like many Canadians, may experience limited access to some health and mental health-care services, particularly in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. In March 2020, the Interim Federal Health Program began providing coverage for tele-services and virtual appointments to facilitate access to care. These services include virtual psychology and psychotherapy services, as well as coverage for interpretation services during the initial assessment treatment sessions, which align with provincial and territorial health insurance programs.

Other examples of federally-funded resources related to mental health and substance use during the COVID-19 pandemic are described in Appendix C.

COVID-19 funding for mental wellness support in Indigenous communities

The COVID-19 pandemic and related public health measures are also having a significant impact on mental wellness in Indigenous populations, magnifying existing mental health issues and inequities, evoking past trauma, and creating new gaps and needs.Footnote 17 In response, the Minister of Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) announced an investment of $82.5 million in mental health wellness supports to help Indigenous communities adapt and expand mental wellness services, improve access and address growing demand during the pandemic.

In addition, there is a wide range of virtual resources available to help Indigenous communities with their mental wellness during and after the COVID 19 pandemic, described in the section of this report on Connecting Canadians, Information, and Resources and in Appendix C.

III. Facts about suicide in Canada

Suicide is a preventable complex public health issue that affects Canadians of all ages, sexes, genders, ethnicities, income levels, and regions. Suicide was the ninth leading cause of death among all Canadians in 2018, and the second leading cause of death among individuals aged 15 to 34, behind unintentional injuries, according to Statistics Canada data.Footnote 18

As part of its role in suicide surveillance, PHAC is documenting how suicide mortality is changing in Canada over time. A recent paper by PHAC researchers Varin et al. (2020) found that Canada's overall suicide rate did not significantly change from 2008 to 2017.Footnote 19

Deaths by suicideFootnote 20

Suicide mortality: Both sexes

10.3

per 100,000 population

3811

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Vital Statistics - Death Database (CVSD), 2018

- In 2018, 3,811 people died by suicide in Canada, corresponding to a suicide mortality rate of 10.3 per 100,000 population.

- More than half of all deaths by suicide were due to suffocation (including hanging and strangulation).

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Vital Statistics - Death Database (CVSD), 2018

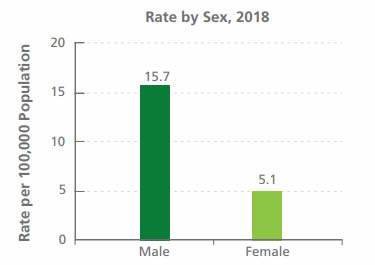

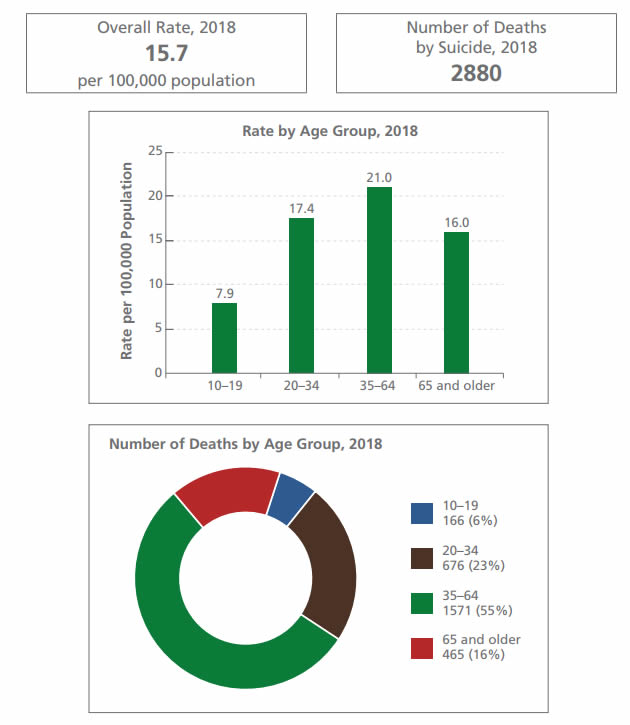

Comparison: Suicide mortality rate by sex - Text description

Rate by Sex, 2018 per 100,000 population: 15.7 Male, 5.1 Female

- In 2018, the suicide mortality rate was more than three times higher among males compared to females. The rate was 15.7 deaths per 100,000 population for males and 5.1 deaths per 100,000 population for females.

- Varin et al. (2020) found that although rates were consistently higher among males, there were significant rate increases over time among females in specific age groups.Footnote 19

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Vital Statistics - Death Database (CVSD), 2018

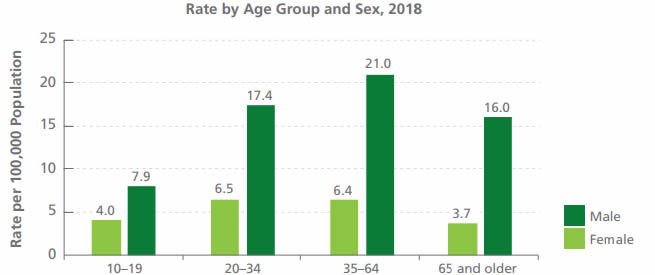

Comparison: Suicide mortality rate by age group and sex - Text description

Rate by age group & sex, 2018 per 100,000 population:

- 10-19: 4.0 Female, 7.9 Male

- 20-34: 6.5 Female, 17.4 Male

- 35-64: 6.4 Female, 21.0 Male

- 65 and older: 3.7 Female, 16.0 Male

- The difference in the suicide rate between males and females was larger in older age groups than in younger age groups. The suicide rate among males was more than four times higher than the suicide rate among females aged 65 and older, and around two times higher among males than the rate among females aged 10-19.

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Vital Statistics - Death Database (CVSD), 2018

Suicide mortality: Males - Text description

- Overall rate, 2018: 15.7 per 100,000 population

- Number of deaths by suicide, 2018: 2880

Rate by age group, 2018, per 100,000 population

- 10-19: 7.9

- 20-34: 17.4

- 35-64: 21.0

- 65 and older: 16.0

Number of deaths by age group, 2018:

- 10-19: 166 (5.8%)

- 20-34: 676 (23.5%)

- 35-64: 1571 (54.6%)

- 65 and older: 465 (16.2%)

- In 2018, 54% of all suicide deaths among males were due to suffocation (including hanging and strangulation), followed by firearms (18%), and poisoning (14%).

Source: Statistics Canada, Canadian Vital Statistics - Death Database (CVSD), 2018

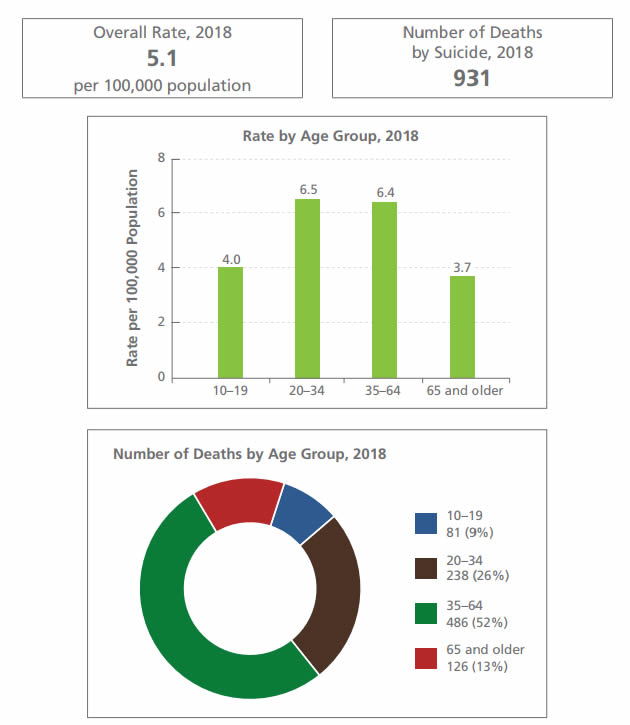

Suicide mortality: Females - Text description

- Overall rate, 2018: 5.1 per 100,000 population

- Number of deaths by suicide 2018: 931

Rate by age group, 2018, per 100,000 population

- 10-19: 4.0

- 20-34: 6.5

- 35-64: 6.4

- 65 and older: 3.7

Number of deaths by age group, 2018:

- 10-19: 81 (8.7%)

- 20-34: 238 (25.6%)

- 35-64: 486 (52.2%)

- 65 and older: 126 (13.5%)

- In 2018, 52% of all deaths by suicide among females were due to suffocation (including hanging and strangulation), followed by poisoning (31%).

Hospitalizations associated with self-harm injuryFootnote 21

Source: Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI), Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) and Ontario Mental Health Reporting System (OMHRS), 2018-2019 fiscal year, excluding Quebec hospitals.

Comparison: Hospitalization rate by sex - Text description

Rate by sex, fiscal year 2018-2019, per 100,000 population: 81 female, 46 male

- There was an approximately 80% higher hospitalization rate associated with self-harm injuries among females compared to males.

Source: Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI), Discharge Abstract Database (DAD) and Ontario Mental Health Reporting System (OMHRS), 2018-2019 fiscal year, excluding Quebec hospitals.

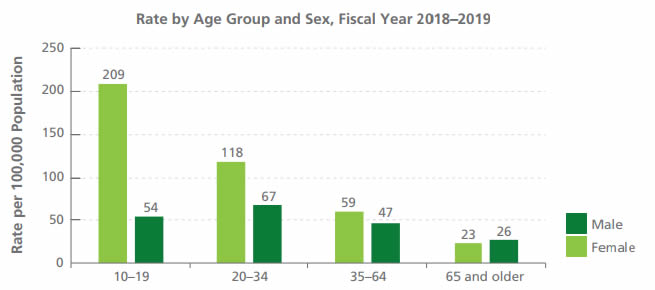

Comparison: Hospitalization rate by age group and sex - Text description

Rate by age group & sex, fiscal year 2018-2019 per 100,000 population:

- 10-19: 209 female, 54 male

- 20-34: 118 female, 67 male

- 35-64: 59 female, 47 male

- 65 and older: 23 female, 26 male

- The difference in the hospitalization rate associated with self-harm injuries for males and females decreased with age. The rate was approximately four times higher among females by comparison to males aged 10-19 years, and was similar for males and females aged 65 and older.

Other suicide related data

In Statistics Canada's Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) 2019,Footnote 13 12% of Canadians reported having thoughts of suicide in their lifetime, and 3% reported having thoughts of suicide in the past twelve months, which are similar to the rates in the CCHS in 2016, the last time thoughts of suicide were measuredFootnote 22

According to 2016 CCHS data, 4% of Canadians reported that they had made a plan to seriously attempt suicide in their lifetime.Footnote 22 People in the lowest income quintile group were more likely to report that they had made plans to attempt suicide in their lifetime: 7% in the lowest income group compared to 3% in the top income group.

Also in the 2016 CCHS, 3% of Canadians reported having attempted suicide in their lifetime.Footnote 22 Suicide attempts were approximately three times higher among people born in Canada than among immigrants to Canada.

Suicide rates among First Nations, Inuit and MétisFootnote 23

In June 2019, Statistics Canada published a report on suicide rates among First Nations people, Inuit and Métis for the 2011-2016 period. The report is the first to examine suicide rates among all three Indigenous peoples, comparing these rates to those among non-Indigenous people in Canada using one single methodology.Footnote 24

The report found that the suicide rate was highest among Inuit (72.3 deaths by suicide per 100,000 persons per year) and, specifically, adolescents and young adults. For First Nations people, the suicide rate was 24.3 deaths by suicide per 100,000 persons per year; the rate among First Nations people living on reserve was higher than for those living off reserve, and higher among males than females. The suicide rate for Métis was 14.7 deaths by suicide per 100,000 persons per year.

Of particular concern is the high rate of suicide among Indigenous children under the age of 15. For example, nationally, the suicide rate among First Nations boys was four times higher than among non-Indigenous boys. It was ten times higher among First Nations boys living on reserve.

There is considerable variability across communities. For example, about 60% of First Nations bands and 11 of 50 Inuit communities have a suicide rate of zero.

The report also found that the combination of geographic (i.e., living on and off reserve or urban/rural area) and socioeconomic factors (i.e., household income, labour force status, level of education, and marital status) accounted for increased risk of suicide among First Nations people (78% of increased risk), Inuit (40%) and Métis (37%), by comparison to non-Indigenous adults.

IV. Update on federal activities

This section of the report begins with a description of holistic approaches to suicide prevention, followed by federal actions contributing to suicide prevention in Canada from November 2018 to November 2020 under the Framework's three strategic objectives:

- Reduce stigma and raise public awareness

- Connect Canadians, information and resources

- Accelerate the use of research and innovation in suicide prevention.

Moving upstream: Holistic approaches to suicide prevention

Over the life course, many factors, including social, economic and physical environments, also known as the social determinants of health, influence individuals' mental health.Footnote 25 While no single cause explains or predicts suicide, the likelihood that someone will think about, attempt, or die by suicide may increase or decrease due to a complex interplay of suicide risk and protectiveFootnote 26 factors, which may include individual, biological, psychological, relational, spiritual, socioeconomic and/or cultural factors.Footnote 27,Footnote 28

Recognizing the complex interplay of risk and protective factors, this segment of the report introduces holisticFootnote 29 approaches to suicide prevention and life promotion that focus on building strengths and consider the role of population health, such as how interventions at the community, policy, and systems-level impact suicide, highlighting Indigenous-led initiatives. Evidence in this area is emerging, as suicide prevention research has typically focussed on evaluating the effectiveness of a single intervention at a time. Evaluating and attributing outcomes from a comprehensive suicide prevention strategy is challenging, but a priority area for research.

In particular, preventing suicide in Indigenous communities needs a holistic, Indigenous-specific, strength-based, distinctions-based, community-driven approach which supports people, families, and communities. Such an approach also needs to address the legacy of residential and day schools, the Sixties' Scoop, and other devastating impacts of colonization as well as focus on current racism, discrimination, and inequities in determinants of health such as basic needs (e.g. clean water, food security, housing, healthy early child development), culture, language, health care, self-determination, education, and employment.

The National Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy (NISPS) and the First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework both outline a holistic approach to mental wellness and suicide prevention grounded in culture and Indigenous-specific determinants of health and aims to create systems change.

National Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy

Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami's (ITK's) National Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy (NISPS) “envisions suicide prevention as a shared national, regional, and community-wide effort that engages individuals, families, and communities. It provides a unified approach to suicide prevention in Inuit Nunangat that […] [promotes] a shared understanding of the context and underlying risk factors for suicide among Inuit, by providing policy guidance at the regional and national levels on evidence-based approaches to suicide prevention, and by identifying stakeholders and their specific roles in preventing suicide. The NISPS outlines how different stakeholders can effectively coordinate with each other to implement a more holistic approach to suicide prevention.”Footnote 30

The NISPS articulates six priority areas that reflect a broad approach to suicide prevention among Inuit in Nunangat:

- Creating social equity,

- Creating cultural continuity,

- Nurturing healthy Inuit children from birth,

- Ensuring access to a continuum of mental wellness services for Inuit,

- Healing unresolved trauma and grief, and

- Mobilizing Inuit knowledge for resilience and suicide prevention.

First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework

The First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework states: “Mental wellness is a balance of the mental, physical, spiritual, and emotional. This balance is enriched as individuals have: purpose in their daily lives whether it is through education, employment, care-giving activities, or cultural ways of being and doing; hope for their future and those of their families that is grounded in a sense of identity, unique Indigenous values, and having a belief in spirit; a sense of belonging and connectedness within their families, to community, and to culture; and finally, a sense of meaning and an understanding of how their lives and those of their families and communities are part of creation and a rich history.”Footnote 31 It also emphasizes that “cultural knowledge about mental wellness does not narrowly focus on ‘deficits.' Rather, it is grounded in strengths and resilience.”Footnote 32

The concept of life promotion is reflected in the First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework, which describes mental wellness as “a broader term that can be defined as a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own potential, can cope with the normal stresses of life, and is able to make a contribution to her or his own community.”Footnote 33

Life promotion and mental wellness

The Promoting Life Together Collaborative with the Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement described Life Promotion as “an Indigenous paradigm shift that encompasses both suicide prevention and life promotion to reduce premature unnatural death.”Footnote 34 It includes building hope and resiliency, giving meaning to life, promoting mental wellness, offering skills and tools to deal with stress, and providing a strong foundation of culture. The Collaborative recognized “the need to take a broader and more encompassing approach to the issue of suicide, to consider all aspects of one's life and community wellness.”Footnote 34

Examples of programs supporting wellness and life promotion that are contributing to suicide prevention in Indigenous communities are described in the section of this report on Connecting Canadians, Information, and Resources.

Examples of PHAC mental health promotion programs acting at individual, family, community and systems levels to address health inequities and act on risk and protective factors for mental health are described in Appendix D.

Strategic objective 1: Reduce stigma and raise public awareness

Reducing stigma and raising awareness

Suicide prevention resources that raise awareness and promote hope

The Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) continues to develop a range of knowledge products, fact sheets, webinars, toolkits, and other learning opportunities that target suicide prevention and life promotion. These evidence-based materials are grounded in the principles of reducing stigma and promoting health equity, to support diverse populations that may be at risk of suicide. For example:

- To increase awareness about the facts related to suicide prevention and to demystify common myths, the MHCC is partnering with the Centre for Suicide Prevention to develop fact sheets on men and suicide, youth and suicide, and suicide in rural and remote areas.

- Community postvention is an important intervention strategy designed to support the needs of a community after someone dies by suicide. As a community-focused approach, it is intended to reduce the risk of contagion through targeted supports and programs. The MHCC is in the process of creating a catalogue of postvention resources to support local suicide prevention efforts in communities across Canada.

- The MHCC continues to support the #sharehope social media campaign to raise awareness and spread hope to people who may be vulnerable to suicide and continues to address stigma through its many training initiatives, such as Headstrong, Mental Health First Aid, and The Working Mind, that tailor content for diverse audiences and build on common themes, like enhancing help seeking and promoting personal mental health.

Rail safety

Transport Canada is committed to protecting all Canadians who live and work along rail lines. This includes implementing measures to reduce and prevent incidents of self-harm and suicide in the context of Canada's rail system. Examples of these measures include:

- Investment in national public information and awareness campaigns, including support for VIA Rail's suicide prevention awareness project. The department also provided support to Operation Lifesaver to deliver a national education campaign on trespassing incidents, particularly in areas with higher rates of such incidents, and is working with provinces to better leverage that initiative.

- Federal funding through Transport Canada's Rail Safety Improvement Program to improve rail safety and help prevent injuries and deaths, including through infrastructure improvements and public education/awareness.

Road to Mental Readiness (R2MR) training

Public Safety Canada is providing $400,000 to Canadian Institute for Public Safety Research and Treatment for Road to Mental Readiness (R2MR) training. R2MR is an evidence-based mental health and education program designed to reduce stigma, as well as to address and promote resilience among public safety personnel,Footnote 36 noting that one of the aims of R2MR is to increase help-seeking behaviour. Its implementation in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF), in conjunction with other evidence-informed workplace mental health programs (e.g., public awareness campaigns, mental health screening programs, and increasing access to mental health services) were shown to benefit CAF members' perceived need for careFootnote 37 and help-seeking behaviour.Footnote 38,Footnote 39

Sixty-six public safety personnel received R2MR training in 2019-20, however the COVID-19 pandemic required the cancellation of in-person training, and CIPSRT is exploring virtual training options.

LGBTQ2 Activities

We know that thoughts of suicide and suicide-related behaviour are disproportionately prevalent among LGBTQ2 populations, particularly youth, compared to their non-LGBTQ2 peers.Footnote 40,Footnote 41 While more work is needed to better understand and address this, federal activities are seeking to address issues specific to LGBTQ2 Canadians, such as the:

- Government of Canada's LGBTQ2 Secretariat, which works with LGBTQ2 stakeholders across the county to help inform the Government on issues and potential solutions; and

- Office of Women and LGBTQ2 Veterans at Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) established in July 2019 to identify and address systemic issues specific to women and sexual/gender-diverse Veterans and their families.

Promoting safe messaging and responsible reporting

Mindset

Mindset was developed by journalists for journalists, journalism educators and students to provide advice when reporting on mental health. Mindset highlights best practices regarding dissecting myths, reducing stigma, and placing stories in proper perspective. The MHCC is currently supporting the Canadian Journalism Forum on Violence and Trauma in revising the content of the guide. The Third Edition was launched on November 30, 2020, and changes include an expanded chapter on reporting on suicide and a new chapter on reporting on mental health stories involving young people.

Language Matters

PHAC published a bilingual resource for Canadians entitled “Language Matters” to promote the use of safe and non-stigmatizing language, including information for communicating and reporting on suicide. This resource was developed in partnership with the Centre for Suicide Prevention and l'Association québécoise de prévention du suicide (AQPS) and is being used or adapted by other organizations, including ITK and AQPS, to tailor information appropriate for different populations. For examples, see ITK's Words Matter and AQPS' How to talk about suicide.

Strategic objective 2: Connect Canadians, information and resources

The Government of Canada continues to support a number of initiatives that connect Canadians, information, and resources on suicide and suicide prevention, including improving access to mental health services and supports.

Connecting Canadians to suicide crisis supports

Supporting a pan-Canadian suicide prevention service

Crisis lines are a widely implemented best practice to reduce immediate suicide risk for people seeking support. The Government of Canada is providing $21 million over five years, starting in 2020-21, to the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) to implement a pan-Canadian suicide prevention service. CAMH will lead this initiative in partnership with the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) and Crisis Services Canada (CSC). This investment builds on PHAC's proof of concept funding to CSC ($5.46 million over five years from 2015-16 to 2020-21).

This service is currently providing suicide prevention crisis support from trained responders via phone (24/7) and text (evenings). Once fully implemented, people across Canada will have access to 24/7/365 crisis support, in English and French, using the technology of their choice: voice, text, or online chat. This support will include immediate access to information and resources such as emergency services, referrals, safety plans, and bereavement support.

CAMH, CMHA, and CSC will enhance this service to meet the needs of all people in Canada in collaboration with people with lived experience, particularly populations with a higher risk of suicide, including some First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities and LGBTQ2 communities and organizations.

Connecting Indigenous communities to Indigenous mental wellness and suicide prevention resources and information

Preventing suicide in Indigenous communities is a key priority for Indigenous leaders, organizations, communities, and youth, and Indigenous Services Canada (ISC).

ISC is guided by the First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework (FNMWCF) and the National Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy (NISPS), two key documents previously mentioned in this report.

Supporting suicide prevention strategies

Budget 2019 announced $50 million over ten years with $5 million ongoing to support the continued implementation of the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami's NISPS. The NISPS has also been used as a guide to develop a regional suicide prevention strategy in Nunavik, which was launched in November 2019. An early evaluation has shown that the NISPS has supported initiatives that have benefited Inuit within Inuit Nunangat. Taking the regional and community context into consideration was highlighted as an important factor in this progress, as was the effectiveness of an Inuit-specific approach.

ISC is also supporting the early implementation of the Federation of Indigenous Sovereign Nation's Saskatchewan First Nations Suicide Prevention Strategy with an investment of $2.5 million over two years.

Supporting Indigenous mental wellness

The Government of Canada has made significant recent investments to improve mental wellness in Indigenous communities, with an approximate annual investment of $425 million. These investments, which include the NISPS and the FNMWCF, are made to meet the immediate mental wellness needs of communities, to support Indigenous-led suicide prevention and life promotion efforts, including through a national crisis helpline and community-driven mental wellness teams, and to enhance the delivery of culturally-appropriate substance use treatment and prevention services in Indigenous communities with high needs. The investments also provide cultural, emotional, and mental health support to former Indian Residential School and Federal Indian Day School students, and their families, and those affected by the issue of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.

The Hope for Wellness Helpline continues to be available for people who are experiencing distress. This helpline provides immediate, culturally safe, telephone and chat crisis intervention services for Indigenous Peoples across Canada. It is available 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Demands for this service have increased significantly since its launch and the COVID-19 pandemic has further increased the need for this service.

In addition, ISC is contributing to the construction and operations of the Nunavut Wellness Centre with up to $47.5 million over five years and $9.7 million ongoing for operations.

Supporting the Youth Hope Fund

Through an investment of $10 million over five years with $3.4 million per year on-going, ISC is supporting the Youth Hope Fund. Launched in 2016, this fund invests in Indigenous youth-led life promotion projects through a distinctions-based approach. The First Nations Youth Hope Fund has been guided by a youth steering committee to identify and fund life promotion projects for First Nations youth. The Inuit Youth Hope Fund is guided by Inuit youth, including the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami's National Inuit Youth Council, with funding supporting regional Inuit youth-led projects on life promotion across Inuit Nunangat.

Supporting We Matter resource development and campaigns

ISC is also providing funding to We Matter, a national Indigenous youth-led organization that supports Indigenous youth on hope and life promotion. Through their national multi-media campaign, toolkits, Ambassadors of Hope program, mini-grant program, strong social media presence, and other initiatives, they have reached many Indigenous youth across Canada. They supported Indigenous youth in creating Calls to Action for governments, Indigenous leadership, communities, employers, media, and the public.

Examples of First Nations mental wellness and suicide prevention initiatives

Wise Practices

The Wise Practices resource provides examples of First Nations community-led initiatives addressing life promotion and suicide prevention. It is a compilation of practices for promoting life among young people based on what is already working and/or showing promise in First Nations communities across the country. The project is committed to reducing suicide and suicidal behaviour among First Nations youth by “leading with the language of life” rather than relying on deficit-centred language or risk factor-based approaches. Two examples of wise practices are:

- The Feather Carriers Program, which is a cultural approach to community mobilization to enhance mental health and the prevention of addictions and suicide using Indigenous knowledge and teachings.

- The Buffalo Riders Early Intervention Training Program, which enhances and strengthens the community-based capacity to provide youth with early and brief support services to reduce substance use behaviour.

Choose Life

The Choose Life initiative of the Nishnawbe Aski Nation (NAN) Territory is geared towards First Nations children and youth in NAN communities at risk of suicide. It implements a simplified process to access funding for mental health services under Jordan's Principle, which ensures that all First Nations children living in Canada can access the products, services and supports they need, when they need them. Choose Life funds enhance mental health and crisis counselling support, peer support programs, art and recreational therapy, school-based support programs, mental health promotion, and training.

Supplementary information: Information and resources related to Métis mental health

Data about suicide among Métis nations is limited and more work is needed to better understand and address suicide among Métis. Recognizing the importance of distinctions-based approaches to suicide prevention and mental health, this segment offers the following examples of non federally-funded available resources related to Métis mental health:

- Métis Nation of Ontario's (MNO) 24-hour Mental Health and Addictions Crisis Line offering culturally specific Métis mental health and addiction supports for adults, youth, and families in Ontario in both English and French at 1-877-767-7572.

- Métis Nation of Alberta's (MNA) Distress Line offers crisis intervention including suicide prevention at 1-780-482-4357, and their Mental Health Help Line which provides information about mental health programs and services at 1-877-303-2642.

Examples of information related to Métis mental health include the following:

- Ta Saantii – A Profile of Métis Youth Health in BC, offering insight into the mental health of Métis youth in British Columbia

- Métis Perspectives of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls and LGBTQ2S+ People, a report addressing the situation of violence against Métis women and girls in Canada to affect meaningful change for Métis women, published by Women of the Métis Nation / Les Femmes Michif Otipemiskiwak (LFMO) in June 2019

- Resilient Roots: Métis Mental Health and Wellness Magazine, published by the Métis Nation of British Columbia.

Connecting military members and veterans to resources and information

Suicide prevention in the Canadian Armed Forces

The Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) continues to implement the Canadian Armed Forces-Veterans Affairs Canada Joint Suicide Prevention Strategy (2017). The strategy is aligned with the approach set out in the Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention and is informed by research and recommendations from two expert panels on suicide prevention in the CAF.

A 2019 survey of CAF members indicated that attitudes toward seeking mental health supports are shifting. Most CAF members indicated that their leaders encouraged members to seek help and did not judge those who sought mental health care. Most were aware of the Suicide Prevention Action Plan (SPAP) health-related programs, with an overall high level of satisfaction for those participating in health programs associated with the SPAP.

Over the last year, there have been technological investments to facilitate remote/virtual mental health counselling and expansion of tailored mental skills training and performance coaching to members in high-stress occupations in the CAF. Frontline workers (such as clinicians, military police, and chaplains) have received specialized training in suicide prevention techniques and coping skills that foster resilience to be better prepared to manage personnel in crisis. Mental Fitness and Suicide Awareness, and Road to Mental Readiness (R2MR) courses continue to be delivered to CAF members and their families across the country to reduce stigma and provide education on suicide prevention, mental health, and positive coping skills.

Online resources like the You Are Not Alone webpage, which assists members and their families in accessing support, had an increased number of views, and the Employee Assistance Program available to employees and family members added LifeSpeak, an online health and wellness resource.

Suicide prevention resources and information for Veterans

The joint Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) – Veterans Affairs Canada (VAC) suicide prevention strategy included department-specific action plans. Of the 63 action items appearing in the VAC Suicide Prevention Strategy Action Plan, 81% have been completed or are ongoing. The following resources have been developed to assist Veterans:

- Through the Department of National Defence, a Veteran Service Card is now available, providing a tangible symbol of recognition for former CAF members and encouraging an enduring affiliation with the CAF.

- The Joint CAF-VAC Transition Trial was launched in February 2019 at the Borden Transition Centre. The new Military-to-Civilian Transition process is for non-medically releasing CAF Members, Veterans and their families. It outlines a collaborative approach between CAF and VAC to support a successful transition to life after service. There is an expansion to a second site in Petawawa, scheduled for January 2021.

- A partnership with the Saint Elizabeth Health Centre has been extended through 2020-2021 to provide the online Caregiver Zone free resource. Caregiver Zone helps caregivers of ill and injured Veterans learn how to better support themselves and their loved ones through treatment and recovery.

Connecting public safety personnel to resources and information

Courses for the Canadian Police Knowledge Network

The MHCC has continued to provide content support to the Canadian Police Knowledge Network's online Suicide Awareness and Prevention courses for employees and supervisors and the Mental Health Self-Awareness for First Responders course. The courses are designed to help members of the policing and first responder community recognize the factors associated with suicide and how to support mental health and well-being in the workplace. The courses review strategies and resources to prevent suicide and address the importance of crisis intervention and overcoming the stigma associated with mental health issues.

Suicide prevention wallet card for the RCMP

Based on best practices in other police services, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) developed a suicide-prevention wallet card. The card lists signs for suicide risk and urges those experiencing or noticing any of the signs in themselves or a colleague to contact the appropriate resources.

Connecting people in federal correctional services to resources and information

In its ongoing efforts to address the mental health needs of federally incarcerated individuals, the Correctional Service of Canada launched a Suicide Prevention and Intervention Strategy in April 2019. The strategy is aligned with the Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention and provides a national structure for suicide prevention, intervention, and postvention activities and informs policy, research, and staff learning initiatives.

A key component of the strategy has been the development of a Clinical Framework for Identification, Management, and Intervention for Individuals with Suicide and Self-Injury Vulnerabilities, which is a coordinated, evidence-based approach to suicide, self-injury assessment and intervention. The Clinical Framework will assist Correctional Service Canada's health care professionals in identifying individuals with suicide/self-injury behaviours early so that proactive treatment plans for managing these needs are developed, with the goal of preventing suicide/self-injury. Together, Correctional Service Canada's Suicide Prevention and Intervention Strategy and Clinical Framework emphasize the importance of interdisciplinary teamwork by connecting individuals with cultural/spiritual resources, encouraging meaningful activity, promoting health and wellness, and facilitating access to mental health care.

Connecting Canadians to information about our shared federal, provincial, and territorial health priorities

In August 2017, all provinces and territories agreed to a Common Statement of Principles on Shared Health Priorities. Following the agreement, the federal government negotiated and signed bilateral agreements with each province and territory that set out details of how each jurisdiction is using federal funding to improve access to home and community care and mental health and addiction services. To support provinces and territories in improving access to these services, the federal government is providing them with $5 billion.

The following provinces/territories have included federally-funded suicide prevention activities in their agreements:

- British Columbia: will leverage existing provincial investments to increase access to culturally safer, trauma-informed and culturally appropriate healing and treatment services and mental health and substance use care. This includes a focused approach to suicide and crisis intervention and response and land-based healing opportunities in certain Indigenous communities.

- Saskatchewan: will expand the capacity to deliver child and youth mental health and addiction treatment along the service continuum, including programs and services that promote better emotional health for children and youth in schools and other places where they spend time. This includes supporting community developed strategies aimed at preventing suicide in targeted communities.

- New Brunswick: will support the implementation of the “Enhanced Action Plan on Addictions and Mental Health”, with one of its priority areas focused on increasing prevention efforts for people at risk of suicide.

- Newfoundland and Labrador: will support the implementation of “Towards Recovery: The Mental Health and Addictions Action Plan for Newfoundland and Labrador”, with one of its guiding pillars focusing on promotion, prevention and early intervention including a focus area on suicide prevention.

- Northwest Territories (NWT): will develop and implement a Territorial Suicide Prevention and Crisis Support Network to support communities in proactive suicide prevention activities as well as provide expert and timely intervention in times of crisis. The large and diverse Indigenous population in NWT highlights the importance of enhancing culturally-appropriate approaches to mental health supports, including the prevention of suicide-related crises and improving the response to community and family needs when a crisis does occur.

Connecting suicide stakeholders and healthcare professionals to information and resources

Co-leading the National Collaborative for Suicide Prevention

The Government of Canada supports collaborative approaches to suicide prevention and life promotion in order to improve information sharing and facilitate opportunities for partnership.

The National Collaborative for Suicide Prevention is a forum comprised of organisations working in suicide prevention and people with lived experience with a focus on knowledge exchange, collaboration, and advocacy in suicide prevention. The Collaborative's Executive Committee includes representation from the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC), the Canadian Association of Suicide Prevention, the Canadian Mental Health Association, the Centre for Suicide Prevention, the Canadian Psychiatric Association and PHAC. In July 2020, a Task Force for Active Rescues among Racialized Populations was created to address racism in wellness check protocols and crisis interventions.

Supporting training for healthcare professionals

The Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) has continued its partnership with the Canadian Association for Suicide Prevention and mdBriefCase to offer an online, accredited suicide prevention module for family physicians and nurses. The training aims to provide health care providers with a greater understanding of the warning signs, appropriate actions to prevent suicide and the need for reduced stigma.

Connecting Canadians to data

Surveys by Statistics Canada

Statistics Canada routinely collects data on suicide thoughts and attempts as well as mental health characteristics through various surveys, including the Canadian Community Health Survey and the Indigenous Peoples Survey. It also produces key indicators such as the mortality rate and potential years of life lost from suicide from Vital Statistics. Statistics Canada's reports related to suicide / mortality / mental health include:

- Sexual orientation and complete mental health

- Life expectancy of First Nations, Métis and Inuit household populations in Canada

- Trends in mortality inequalities among the adult household population

- Socioeconomic disparities in life and health expectancy among the household population in Canada

- Social isolation and mortality among Canadian seniors

Suicide Surveillance Indicator Framework data tool

In 2019, PHAC published the Suicide Surveillance Indicator Framework (SSIF) data tool on the Public Health InfoBase, a publicly available, searchable, online visualization tool.Footnote 42 It provides information on suicide and self-inflicted injury outcomes and associated risk and protective factors. The SSIF contains a core set of indicators including suicide deaths, attempts and ideation as well as risk and protective factors at the individual, family, community and societal level.

Strategic objective 3: Accelerate the use of research and innovation in suicide prevention

The Government of Canada continues to support and perform research on effective interventions and best practices to advance the field of suicide prevention based on the best available evidence for research and practice, while also addressing gaps in data to better guide suicide prevention efforts.

Developing a Shared Canadian Research and Knowledge Translation Agenda on Suicide and its Prevention

PHAC continues to collaborate with MHCC on the development of a national suicide prevention research and knowledge translation agenda that will address the lack of alignment in research across the country. Following the literature review and stakeholder consultations in the first phase, PHAC and MHCC are engaging with community-based organizations, universities and researchers with expertise and perspectives related to populations with higher rates of risk of suicide, including: LGBTQ2, men and boys, older adults, rural and remote populations, and youth. This will inform the final report on research priorities in suicide and its prevention.

Supporting Roots of Hope: A community suicide prevention project

Aiming to reduce the impacts of suicide within communities across Canada, MHCC has continued its work on the Roots of Hope Research Demonstration Project. Multi-site and community-led, the project builds upon community expertise to implement suicide prevention interventions that are tailored to the local context. There are currently eight communities participating in the project: Burin Peninsula in Newfoundland and Labrador, Madawaska/Victoria in New Brunswick, La Ronge, Meadow Lake and Buffalo Narrows in Saskatchewan, Edmonton in Alberta, Iqaluit in Nunavut, and Waterloo/Wellington in Ontario. Officially launched on September 5, 2019, the Roots of Hope project will lead to the development of an evidence base, including best practices and suicide prevention guidelines and tools, to support the scale up and implementation of this “made-in-Canada” model across the country.

Strengthening suicide data

Shared Health Priorities indicators

The Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) leads on the development and reporting of various indicators, including:

- Twelve pan-Canadian indicators measuring access to mental health and addictions services and home and community careFootnote 43 related to the Common Statement of Principles on Shared Health Priorities mentioned previously in this report. Over time, these indicators will tell a clearer story about access to care across the country, identify gaps in services, and help make meaningful changes to improve the experiences of Canadian patients and their families.

- A new indicator since 2020, on Self-harm, Including Suicide indicator. This indicator measures the rate of hospital stays for and deaths from intentional self-harm.

- (Since 2019), Hospital Stays for Harm Caused by Substance Use and Frequent Emergency Room Visits for Help with Mental Health and/or Addictions, with updated results released in 2020. While not suicide specific, they provide a comparable picture of access to mental health and addiction services in Canada.

Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Data Tool

PHAC, in collaboration with its partners in the Pan-Canadian Health Inequalities Reporting Initiative, is updating and expanding the Health Inequalities Data Tool with results based on available data for suicide, perceived mental health and mental illness hospitalization. In the next iteration of the data tool, readers will be able to sort indicators of suicide and mental illness hospitalization by individually-linked socioeconomic and sociodemographic variables. Moreover, mental health indicators available in the Data Tool will include findings for less densely populated provinces and territories. Suicide, low self-rated mental health and mental illness hospitalization were among the 22 indicators profiled in the Key Health Inequalities in Canada report published in 2018. Infographics for each of these indicators were produced in 2018 and 2019: Inequalities in Perceived Mental Health in Canada; Inequalities in Mental Illness Hospitalization in Canada and; Inequalities in Death by Suicide in Canada. The Initiative is currently exploring approaches for reporting on changes over time.

Canadian Census Health and Environment Cohorts

Statistics Canada's Canadian Census Health and Environment Cohorts (CanCHECs) are population-based linked datasets of the household population at the time of census collection. The CanCHECs combine data from respondents to the long-form census or the National Household Survey between 1991 and 2016 with administrative health data (e.g., mortality, hospitalizations, emergency ambulatory care) and annual mailing address postal codes. With the CanCHECs, it is now possible to examine health outcomes (e.g., death by suicide, hospitalizations due to self-harm) by socioeconomic characteristics such as income, education and occupational skill level; by specific occupation, occupational group and job characteristic; by population group, such as Indigenous peoples and immigrants; and the measurement of the effect of environmental exposures on health.Footnote 44

Canadian Coroner and Medical Examiner Database

Statistics Canada is making increased use of the Canadian Coroner and Medical Examiner Database. For instance, a recent report examined the employment histories and income sources of people who died of an illicit drug overdose in British Columbia from January 1, 2007, to December 31, 2016.Footnote 45 This is of interest from a suicide prevention perspective as some illicit drug overdose deaths may be suicides.

Understanding factors associated with suicide in Canadian Veterans

VAC examined suicide mortality trends over a 39-year period, which demonstrated that Veterans had a consistently higher rate of suicide death than the Canadian general population, with young male Veterans at the highest rate. The 2019 Veteran Suicide Mortality Study was released in June 2020.Footnote 46

The following two articles were published in July 2019:

- Group identity, difficult adjustment to civilian life, and suicidal ideation in Canadian Armed Forces Veterans: Life After Service Studies;Footnote 47 and

- The Life Course Well-Being Framework for Suicide Prevention in Canadian Armed Forces Veterans.Footnote 48

In 2018 and 2019, 43 projects were approved through the Veteran and Family Well-Being Fund, which encourages innovation and research related to issues Veterans and their families are facing as part of the transition experience to civilian life.

Strengthening Indigenous data

Inuit data on risk and protective factors for suicide

CCSA is collaborating with Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK) on a project to collect and analyze data on risk (including substance use) and protective factors for suicide. Its purpose is to address the gap in knowledge about indicators of suicide in Inuit populations and to inform future priorities developed by their National Inuit Suicide Prevention Strategy (NISPS) working group. A report summarizing the prevalence of selected risk and protective factors, including substance use, will be developed in 2021 and will include a regional comparison of risk and protective factors stratified by age and sex.

Métis Nation health data and strategy

Budget 2018 committed $6 million over five years to support the Métis Nation in gathering Métis Nation health data and developing a health strategy. PHAC entered into six five-year grant agreements with the Métis National Council (MNC) and its five Governing Members to support projects that increase capacity to gather and analyze Métis relevant data to better understand health status.

First Nations Data Governance Strategy

Funded through Budget 2018, the First Nations Data Governance Strategy envisions a First Nations‑led, national network of regional information governance centres across the country equipped with the knowledge, skills, and infrastructure needed to serve the information needs of First Nations people and communities. The First Nations Information Governance Centre regularly gathers health data through the First Nations Regional Health Survey to assist communities in health planning and service delivery.

Supporting research innovation in Indigenous communities

Smart Cities Challenge winners: Katinnganiq: Community, Connectivity, and Digital Access for Life Promotion in Nunavut

In May, 2019, the Smart Cities ChallengeFootnote 49 awarded Katinnganiq: Community, Connectivity, and Digital Access for Life Promotion in Nunavut $10 million over five years to implement protective and preventative measures, to reduce the risk of suicide in Nunavut, and increase the amount and accessibility of peer support networks, educational resources and creative outlets that promote positive mental health to all Nunavummiut (people of Nunavut).

Katinnganiq is based on and guided by Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit, the Inuit knowledge system and worldview that provides the foundations upon which social, emotional, spiritual, cognitive, and physical well-being define health and wellness. In particular, the initiative aligns with the objectives of strengthening self-reliance, wellbeing, and distinct territorial identity (Inuusivut); enhancing education, training and employment (Sivummuaqpalliajjutivut); and working in partnership to advance the goals and aspirations of Nunavummiut (Katujjiqatigiinnivut).

This initiative will see the creation of a network of Makerspaces which offer a gathering space (both physical and digital spaces) for people to come together to be creative, using a mix of technology learning, digital fabrication, open hardware, software hacking and traditional crafts to innovate for themselves. The project will leverage digital access and connectivity to increase the availability and accessibility of mental health resources and support systems.

Pathways to Health Equity for Aboriginal Peoples

CIHR's Pathways to Health Equity for Aboriginal Peoples initiative (Pathways) aims to promote health equity among Indigenous peoples, including in the area of suicide prevention and mental wellness. The suicide related health research projects funded through Pathways will help develop the evidence base on how to design, offer and implement programs and policies that prevent suicide and promote health and wellness for Indigenous Peoples.

Indigenous Healthy Life Trajectories

CIHR's Indigenous Healthy Life Trajectories Initiative focuses on enabling the development of Indigenous focused interventions designed to improve health outcomes, including mental wellness, across the lifespan for Indigenous boys, girls, women and men, gender-diverse and Two-Spirit individuals in Canada. For example, in 2019, CIHR announced funding for research focused on learning how to improve health and wellness for Indigenous children, including a specific focus on understanding how to reduce mental health problems such as anxiety, depression, substance use and suicide.

Network Environments for Indigenous Health Research

The CIHR Network Environments for Indigenous Health Research (NEIHR) Program, a $100.8 million investment over 16 years, has been developed to address needs in Indigenous community capacity development, research and knowledge translation, in multiple areas, including mental health. This includes $3.85 million provided in 2019 for five years to a team of researchers that will develop a cultural evidence-based Indigenous research network to improve mental wellness by generating data that shows that illness and crisis can be prevented with traditional knowledge, cultural safety, and Indigenous science.

Piloting innovation: using AI to detect suicide ideation

PHAC is collaborating with an artificial intelligence (AI) company on a feasibility study that examines the use of AI and machine learning to detect suicide ideation using retrospective Twitter data. Traditional data on suicide mortality and hospitalizations are often delayed or only capture individuals who receive medical care. Social media can provide timely information, and provides an opportunity to improve public health surveillance. Initial results suggest that these types of data tools could be a complementary data source for suicide surveillance. In addition, the development of an accompanying visualization tool as part of this feasibility study has the potential to aid public health surveillance. Risk factor analyses demonstrated that feelings and/or symptoms of depression were the largest factor of suicide ideation. This type of content was mentioned in more than 40% of the tweets where suicide ideation was expressed. Results also showed that tweets containing feelings and/or symptoms of depression were more prevalent during evenings and overnight, and on Mondays, Sundays, and Saturdays. PHAC is exploring potential ways to expand on this initial feasibility study.

Understanding suicide through modeling

The University of Saskatchewan, in collaboration with PHAC, has developed a dynamic model of suicide in Canada, which also applies machine learning, and can be used to simulate suicide deaths as well as the projected impact of several suicide prevention interventions. This model was presented at the International Association for Suicide Research Summit in October 2019 and an article will be submitted to a peer-reviewed journal in the winter of 2021. This model is currently being adapted to simulate suicide deaths during the COVID-19 outbreak. PHAC is also leading a systematic review on universal suicide prevention interventions in high-income Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries to inform future suicide modeling. The systematic review was submitted to a peer-reviewed journal and should be published in the first half of 2021.

Undertaking analyses on risk factors

Alcohol and other drugs and suicide: Opportunities to inform prevention

The use of alcohol and other drugs is recognised as a risk factor for suicide-related behaviour. PHAC and collaborators conducted a narrative review to summarize the literature on the contributions of alcohol and other drugs to suicide in Canada.Footnote 50 Studies summarized in this paper demonstrated an association between population levels of alcohol consumption and suicide mortality rates, and estimated that during the period in question, approximately a quarter of suicide deaths in Canada were alcohol-attributable. Relatively few studies were able to report on the use of alcohol at the time of suicide death as measured through toxicology analyses. The results of this review highlighted the need for systematic documentation and data infrastructure for timely and consistent data. These types of data will support the development of much needed guidance for clinical practice, prevention strategies and policy initiatives.

Thoughts of self-harm among postpartum women