Annual Report on the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act 2022 to 2023

On this page

- Message from the Chief Human Resources Officer

- About this report

- Organizational enquiries and disclosures

- Investigations, findings and corrective measures

- Education and awareness activities

- Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer: activities to support ethical workplaces

- Appendix A: Summary of Disclosure-Related Organizational Activities

- Appendix B: Public Service Employee Survey – Ethics in the Workplace

- Appendix C: Disclosure Process Under the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act

- Appendix D: Key Terms

Message from the Chief Human Resources Officer

I am pleased to present the 16th annual report on the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act to the President of the Treasury Board for tabling in Parliament. As required under the Act, it provides an overview of disclosure-related activities in federal public sector organizations for the 2022–23 fiscal year.

Throughout the 16 years since the Act came into force, it has served as an important support for a public sector culture based on values and ethics. It led to the creation of the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector that describes the values and expected behaviours that guide public servants in all activities related to their professional duties, and requires that all organizations must have their own specific codes of conduct consistent with it.

The act created mechanisms to allow public servants to come forward if they believe that serious wrongdoing has occurred or is about to occur in the workplace. Since reporting wrongdoing takes courage, the Act provides public servants with important protections from reprisal if they come forward in good faith to disclose serious wrongdoing in the workplace.

As outlined in this report, over the years, we have seen a steady number of enquiries and allegations, demonstrating employees’ awareness of the Act and their willingness to report wrongdoing. We need to continue to build this awareness and confidence in the protections for public servants who disclose wrongdoing.

Employees continue to report wrongdoing across the public sector and the number of organizations conducting investigations into allegations of serious wrongdoing and taking corrective measures when those allegations are founded has risen. In this way, each disclosure and investigation contribute to the continuous improvement of the public sector.

To ensure that the PSDPA continues to meet its intended goals, the President of the Treasury Board announced in November 2022 the appointment of a task force of experts to explore revisions to the Act. The task force will produce a public report that provides recommendations on possible amendments to the Act to further support and protect federal public servants who come forward to disclose wrongdoing.

My office will continue to support the President of the Treasury Board in carrying out her mandate commitment of improving government whistleblower protections and supports.

All these efforts are key to maintaining the integrity of Canada’s public sector and Canadians’ trust in government. My office is committed to these goals and will continue to work to promote a healthy, respectful, and inclusive public service.

I invite you to read this report to familiarize yourself with the work under the federal disclosure system, and how the Government of Canada is addressing wrongdoing and supporting values and ethics within the federal public sector.

About this report

The Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (the Act) provides federal public sector employees with:

- a secure and confidential process for disclosing serious wrongdoing in the workplace

- protection from acts of reprisal

This annual report on the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (the Act) covers the period from April 1, 2022, to March 31, 2023. The report contains information on disclosure activities in the federal public sector, which includes departments, agencies and Crown corporations, as defined in section 2 of the Act. The report also contains information on the activities that the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer (OCHRO) has undertaken over the same period to foster an ethical workplace culture.

Every organization subject to the Act is required to designate a senior officer for internal disclosure who is responsible for:

- addressing disclosures made under the Act

- establishing internal procedures to manage disclosures

Alternatively, organizations that are too small to designate a senior officer or establish their own internal procedures can have disclosures handled directly by the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada (PSIC).

The Act requires chief executives of federal organizations to submit a report at the end of the financial year to the Chief Human Resources Officer on disclosures made under the Act within their organization. This report compiles the information received. It does not contain information about:

- disclosures or reprisal complaints made to the PSIC, which are published in the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada’s Annual Report

- other recourse mechanisms

- anonymous disclosures

Organizational enquiries and disclosures

Enquiries

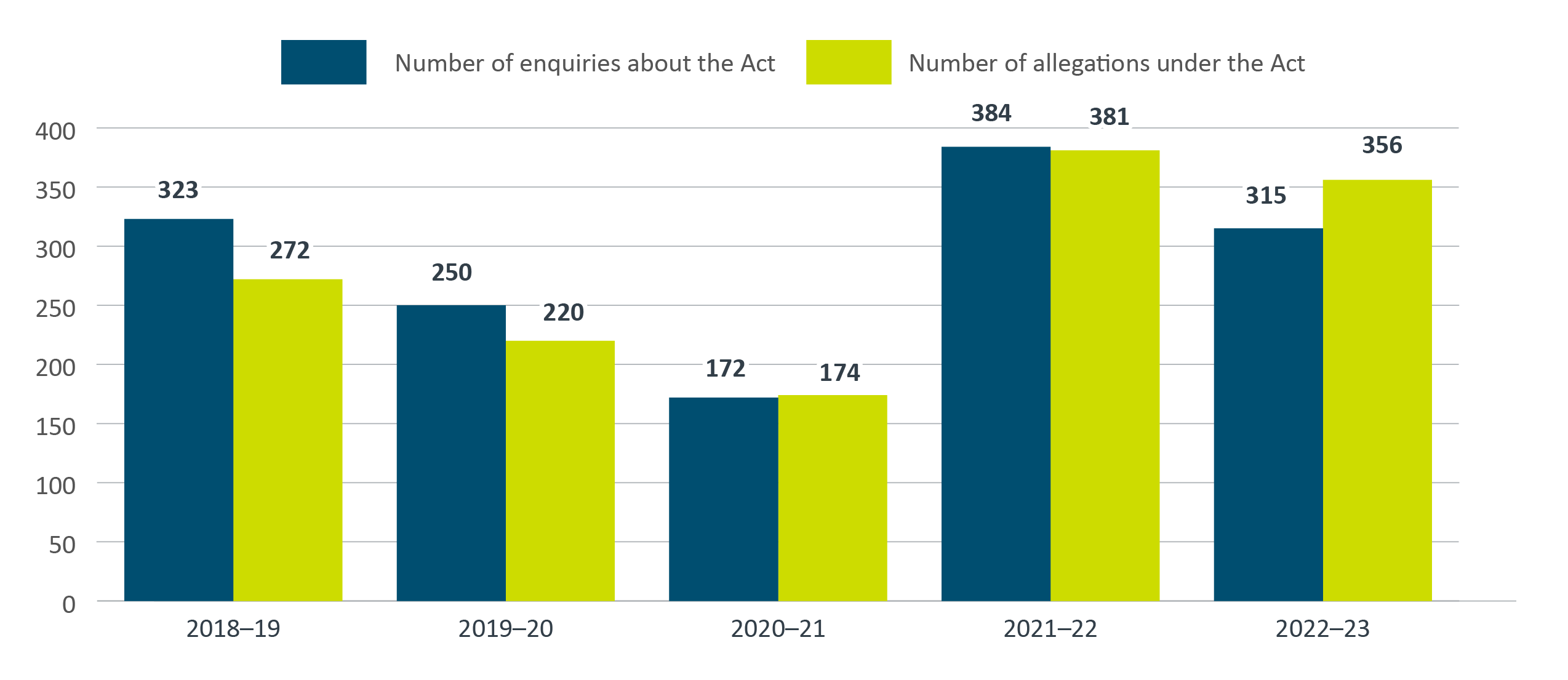

Public servants may make enquires about possible wrongdoings and about how to make a disclosure without formally reporting a disclosure or allegation. In the 2022–23 fiscal year, 315 enquiries were made about the Act (see Figure 1).

Disclosures and allegations of wrongdoing

A disclosure occurs when a public servant or a group of public servants give information to their supervisor or senior officer for internal disclosure about possible wrongdoing in the public sector.

An allegation refers to a public servant communicating a potential instance of wrongdoing as defined in section 8 of the Act. An allegation must be made in good faith, and the person making it must have reasonable grounds to believe that it is true. A disclosure can involve several allegations.

In 2022–23, 152 public servants made 246 internal disclosures concerning 356 allegations of wrongdoing. This compares to 194 public servants who made 178 internal disclosures concerning 381 allegations of wrongdoing in 2021–22.

Figure 1 - Text version

| Type | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | 2022–23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of enquiries about the Act | 323 | 250 | 172 | 384 | 315 |

| Number of allegations under the Act | 272 | 220 | 174 | 381 | 356 |

There were fewer enquiries and allegations in 2022–23 than in 2021–22. However, the number of allegations made in 2022–23 is higher than in the three fiscal years before 2021–22. As noted in last year’s report, from 2019–20 to 2020–21, the COVID‑19 pandemic and remote work may have affected the numbers of enquiries and allegations received.

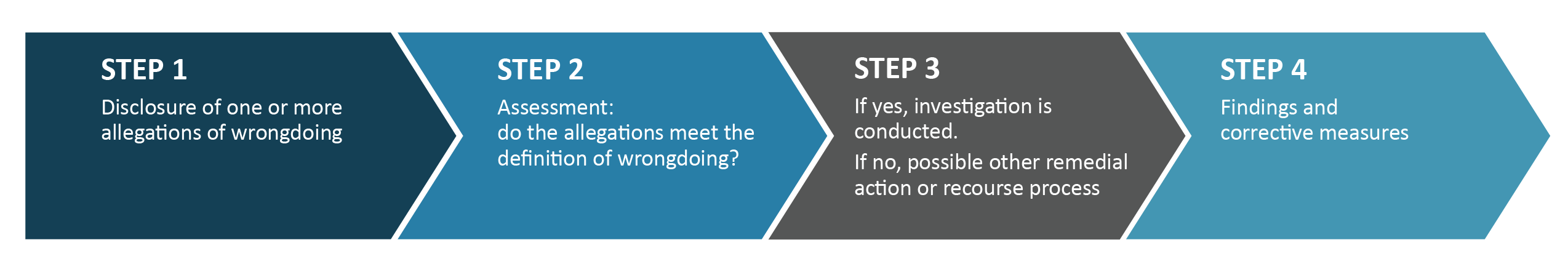

The disclosure process

In general, the disclosure process follows the four steps of:

- receiving a disclosure, which may contain one or multiple allegations

- assessing the allegation(s)

- investigating the allegation(s)

- reporting the findings of the investigation

Figure 2 - Text version

- Step 1: Disclosure of one or more allegations of wrongdoing

- Step 2: Assessment: do the allegations meet the definition of wrongdoing?

- Step 3: If yes, investigation is conducted. If no, possible other remedial action or recourse process

- Step 4: Findings and corrective measures

Step 1: disclosures and allegations

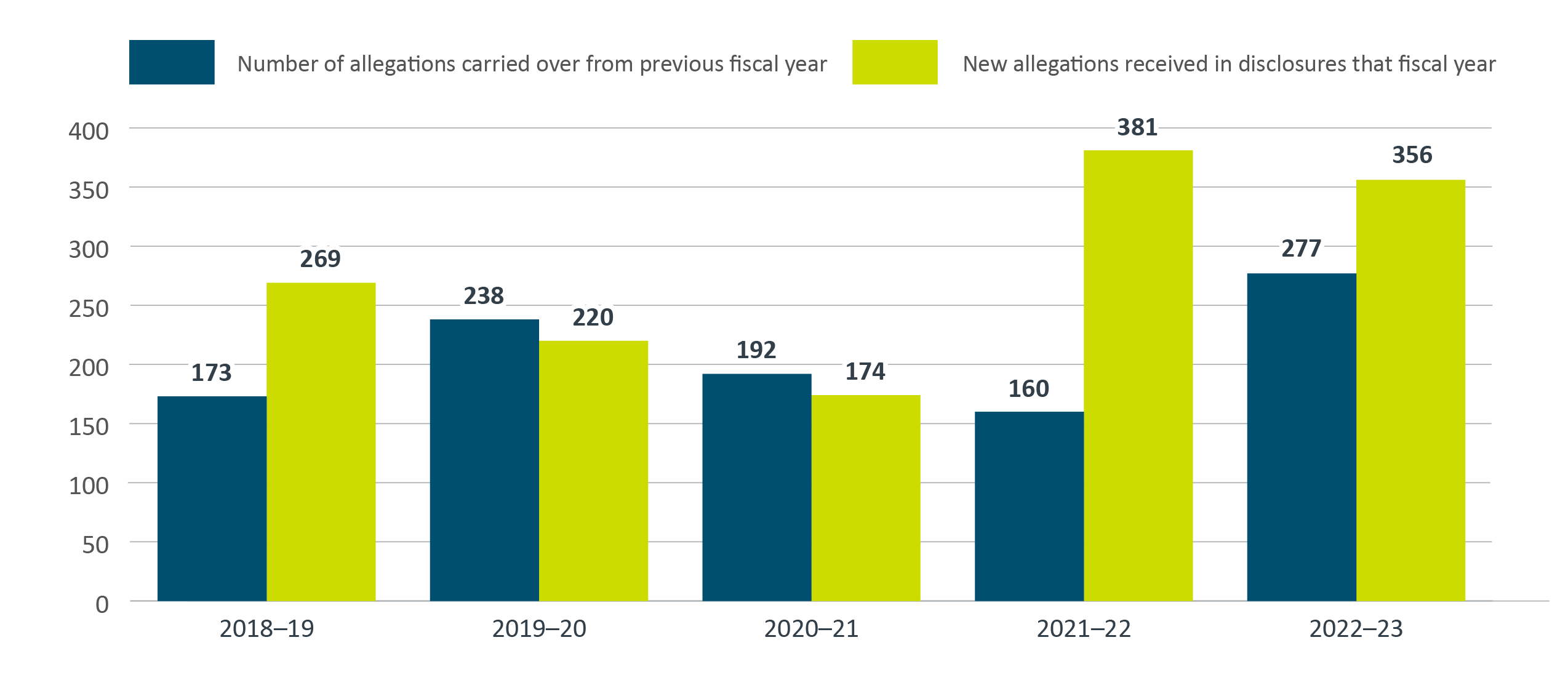

Depending on the complexity of an investigation and the volume of new allegations received, some allegations are carried over into future years before they are resolved.

As shown in Figure 3, in 2022–23, there was an increase in the number of allegations carried over from the previous fiscal year, from 160 allegations in 2021–22 to 277 in 2022–23. Of the 277 allegations carried over from 2021–22 to 2022–23, 207 (75%) were originally received in 2021–22 and 70 (25%) were originally received in 2020–21 or before.

Reports from federal organizations indicate that delays in the handling of allegations (assessing, investigating and reporting) are often associated with resource limitations, the need to interview multiple witnesses or respondents and the need to address complex legal implications.

These factors result in longer process times and allegations being carried over in the next fiscal year.

Figure 3 - Text version

| Type | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | 2022–23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of allegations carried over from previous fiscal year | 173 | 238 | 192 | 160 | 277 |

| New allegations received in disclosures in fiscal year | 269 | 220 | 174 | 381 | 356 |

Step 2: assessment of allegations

Each allegation is assessed by the organization’s senior officer for internal disclosure to determine whether it either:

- falls within the Act’s definition of wrongdoing and warrants further action

- it should be referred to another recourse mechanism

Allegations that are not assessed by March 31 are carried over to the following fiscal year.

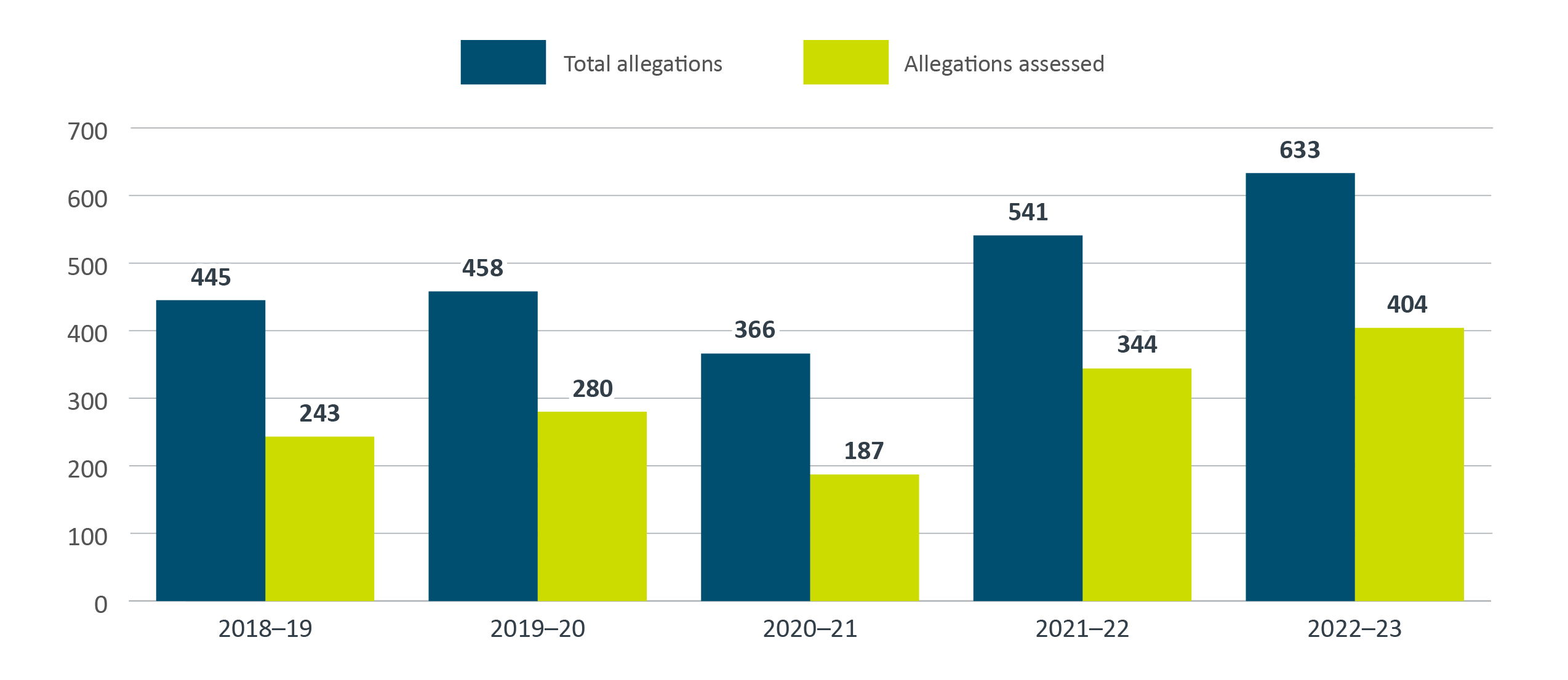

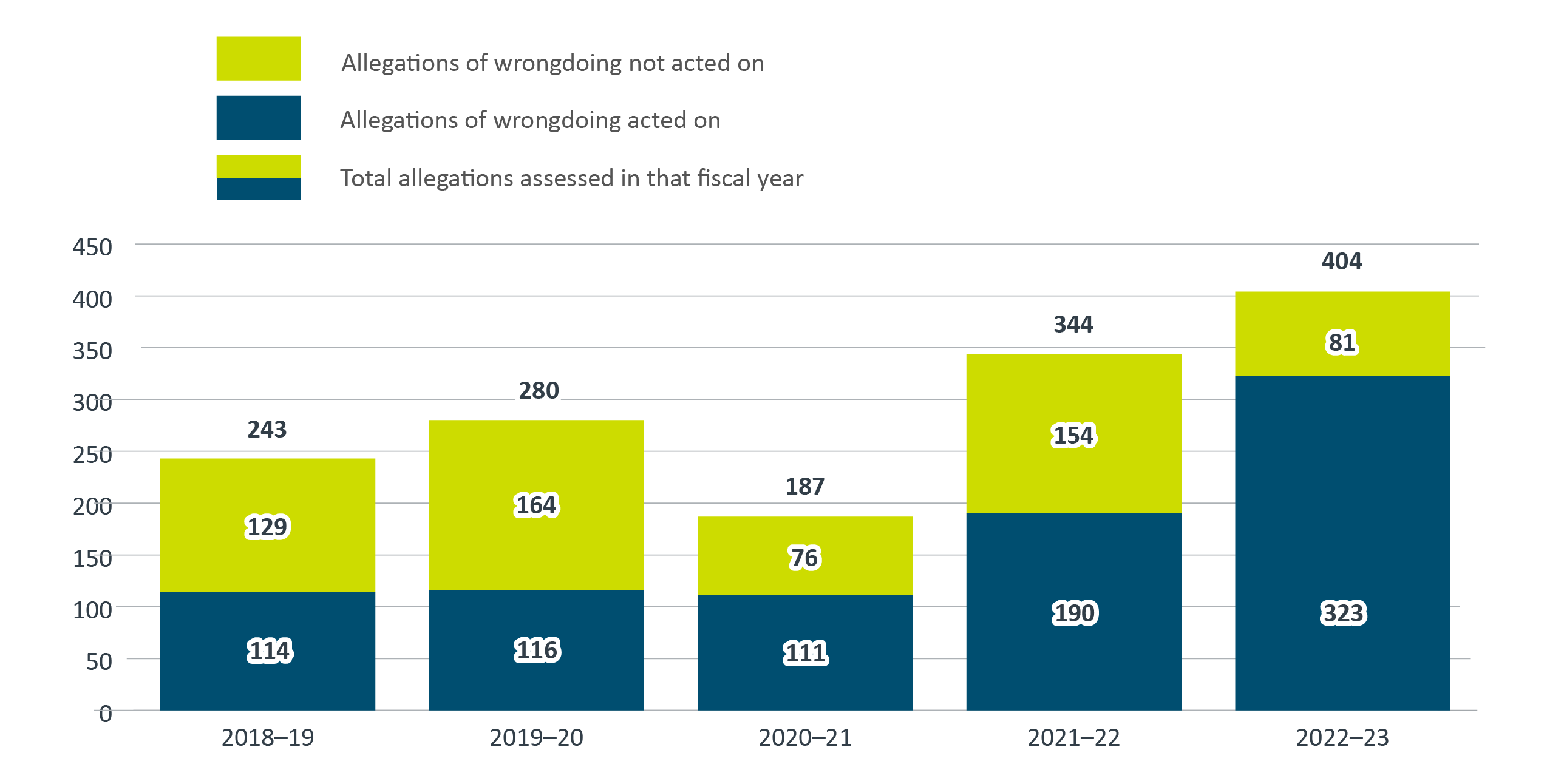

In 2022–23, there were more allegationsFootnote 2 assessed than the number of allegations received. These assessments included allegations carried over from previous fiscal years.

More allegations were assessed in 2022–23 than in 2021–22. Of the 633 total allegations that were active in 2022–23, which included allegations carried over from previous fiscal years and those newly received during 2022–23, 404 (64%) were assessed in 2022–23. The 2022–23 rate of assessment is equal to the previous fiscal year, during which 64% (344 of 541 total allegations) were assessed.

Figure 4 - Text version

| Type | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | 2022–23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total allegations | 445 | 458 | 366 | 541 | 633 |

| Allegations assessed | 243 | 280 | 187 | 344 | 404 |

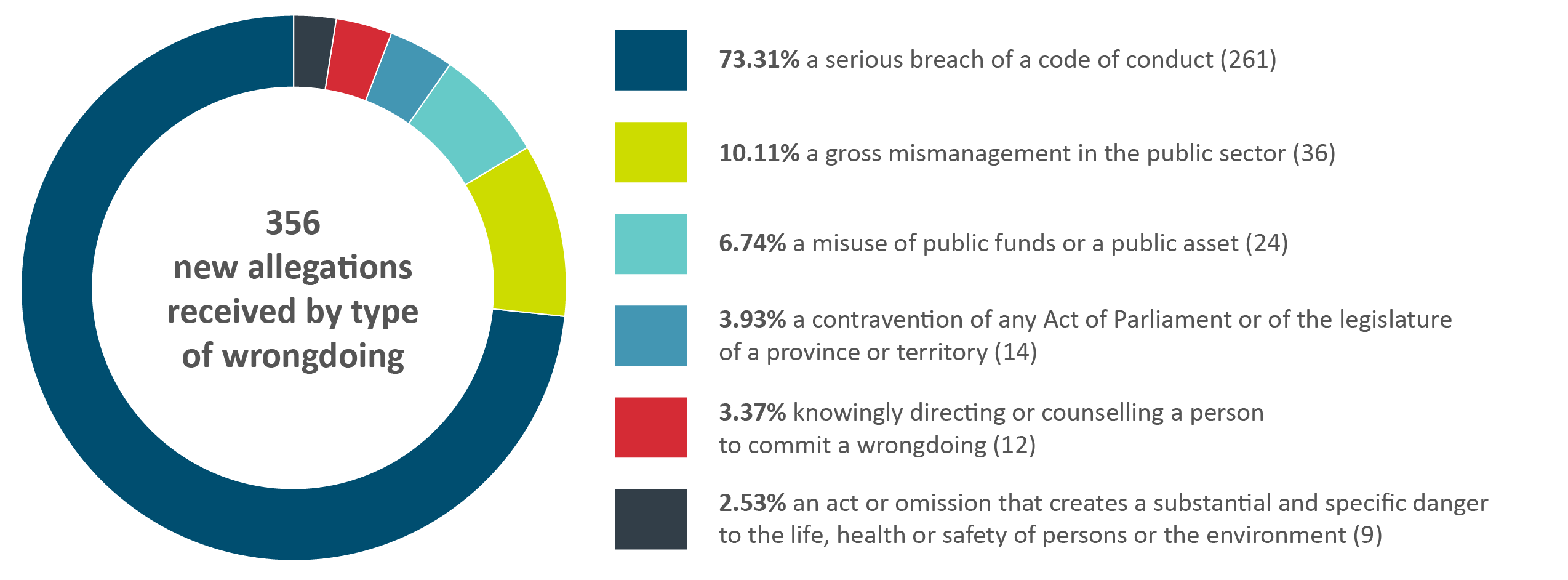

New allegations received in 2022–23

Each allegation is categorized under one of the six types of wrongdoing specified in section 8 of the Act. Of the 356 allegations received in 2022–23, 261 (73%) were categorized as a serious breach of a code of conduct (see Figure 5), which is an increase. There were 192 allegations in this category in 2021–22.

This increase could be because codes of conduct set out clear standards for behaviour in the workplace, which helps employees identify and categorize a breach. If there is an increase in the number of breaches reported, it can mean that employees need to know more about what behaviour is expected and have greater exposure to positive examples and/or awareness-raising activities in organizations have encouraged public servants to report potential breaches.

Some organizations have reported that enquiries and disclosures increase following related awareness activities.

Figure 5 - Text version

| Type | ||

|---|---|---|

| A serious breach of a code of conduct (261) | 73.31% | 261 |

| Gross mismanagement in the public sector (36) | 10.11% | 36 |

| A misuse of public funds or a public asset (24) | 6.74% | 24 |

| A contravention of any Act of Parliament or of the legislature of a province or territory (14) | 3.93% | 14 |

| Knowingly directing or counselling a person to commit a wrongdoing (12) | 3.37% | 12 |

| An act or omission that creates a substantial and specific danger to the life, health or safety of persons or the environment (9) | 2.53% | 9 |

| Total | 100.00% | 356 |

In 2022–23, there were 36 allegations that involved gross mismanagement compared with 74 in 2021–22.

Allegations that involve an act or omission that creates a substantial and specific danger to the life, health or safety of people or of the environment decreased. There were 31 such allegations in 2021–22 in comparison to nine in 2022–23.

Allegations that met the definition of wrongdoing in 2022–23

Of the 404 allegations assessed, in 2022–23, 323 were found to have met the definition of wrongdoing under the Act. Of these 323 allegations:

- 241 were received in 2022–23

- 54 were received in 2021–22

- 28 were received in 2020–21 or earlier

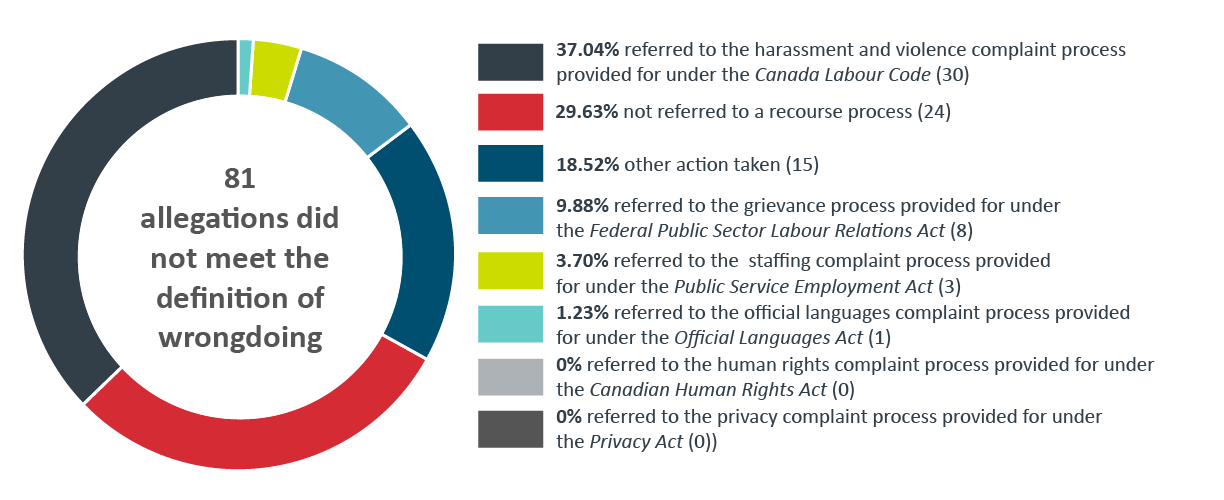

In total, 81 of the 404 assessed allegations did not meet the definition of wrongdoing as specified in the Act or were referred to another mechanism. Of these 81 allegations:

- 53 were received in 2022–23

- 28 were received in 2021–22

As shown in Figure 6, from 2018–19 to 2021–22, the number of allegations that met the definition of wrongdoing and that were acted upon within the same fiscal year has fluctuated between 41% and 59% until 2022–23, when 80% of allegations assessed were acted upon (323 of 404).

Figure 6 - Text version

| Type | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | 2022–23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allegations of wrongdoing not acted upon | 129 | 164 | 76 | 154 | 81 |

| Allegations of wrongdoing acted upon | 114 | 116 | 111 | 190 | 323 |

| Total allegations assessed in fiscal year | 243 | 280 | 187 | 344 | 404 |

In 2022–23, 81 allegations did not meet the definition of wrongdoing as set out in the Act or were referred to another process. Figure 7 illustrates what actions were taken in those cases.

Twenty-four of the 81 allegations were not referred to another recourse process, and 15 allegations required no further action.

Figure 7 - Text version

| Type | ||

|---|---|---|

| Referred to the harassment and violence complaint process provided for under the Canada Labour Code (30) | 37.04% | 30 |

| Not referred to a recourse process (24) | 29.63% | 24 |

| Other action taken (15) | 18.52% | 15 |

| Referred to the grievance process provided for under the Federal Public Sector Labour Relations Act (8) | 9.88% | 8 |

| Referred to the staffing complaint process provided for under the Public Service Employment Act (3) | 3.70% | 3 |

| Referred to the official languages complaint process provided for under the Official Languages Act (1) | 1.23% | 1 |

| Referred to the human rights complaint process provided for under the Canadian Human Rights Act (0) | 0.00% | 0 |

| Referred to the privacy complaint process provided for under the Privacy Act (0) | 0.00% | 0 |

| Total | 100.00% | 81 |

Investigations, findings and corrective measures

Step 3: investigations

A formal investigation refers to a review of all relevant evidence, witness testimonials, and the drawing of conclusions as to whether a disclosure is founded. An investigation may look into one or more allegations. A preliminary analysis or fact-finding that happens at the assessment step and does not lead to a formal investigation is not counted as an investigation; however, assessment can still lead to corrective measures.

In 2022–23, 50 formal investigations were launched, in comparison to 85 formal investigations launched in 2021–22. Of the 50 investigations:

- 19 were based on allegations made in 2022–23

- 19 were based on allegations made in 2021–22

- 12 were based on allegations made in 2020–21 or earlier

By March 31, 2023, 20 investigations were closed. Of these 20 investigations:

- 6 examined 13 allegations made in 2022–23

- 7 examined 18 allegations made in 2021–22

- 7 examined 19 allegations made in 2020–21 or earlier

There were 30 investigations still ongoing at the end of 2022–23 that will be carried over to 2023–24. Thirteen of these investigations are from 2022–23. Twelve are still ongoing from 2021–22, and five are from previous years.

To improve federal organizations’ capacity to investigate disclosures of wrongdoing, a National Master Standing Offer (NMSO) of experts who can investigate allegations has been created. The renewed list became available to organizations in December 2022. It is continuously updated, and new resources are regularly assessed.

During 2022–23, seven organizations used the NMSO. They found it useful for accessing bilingual third-party investigators. The NMSO has also been helpful for smaller organizations that have limited investigative capacity.

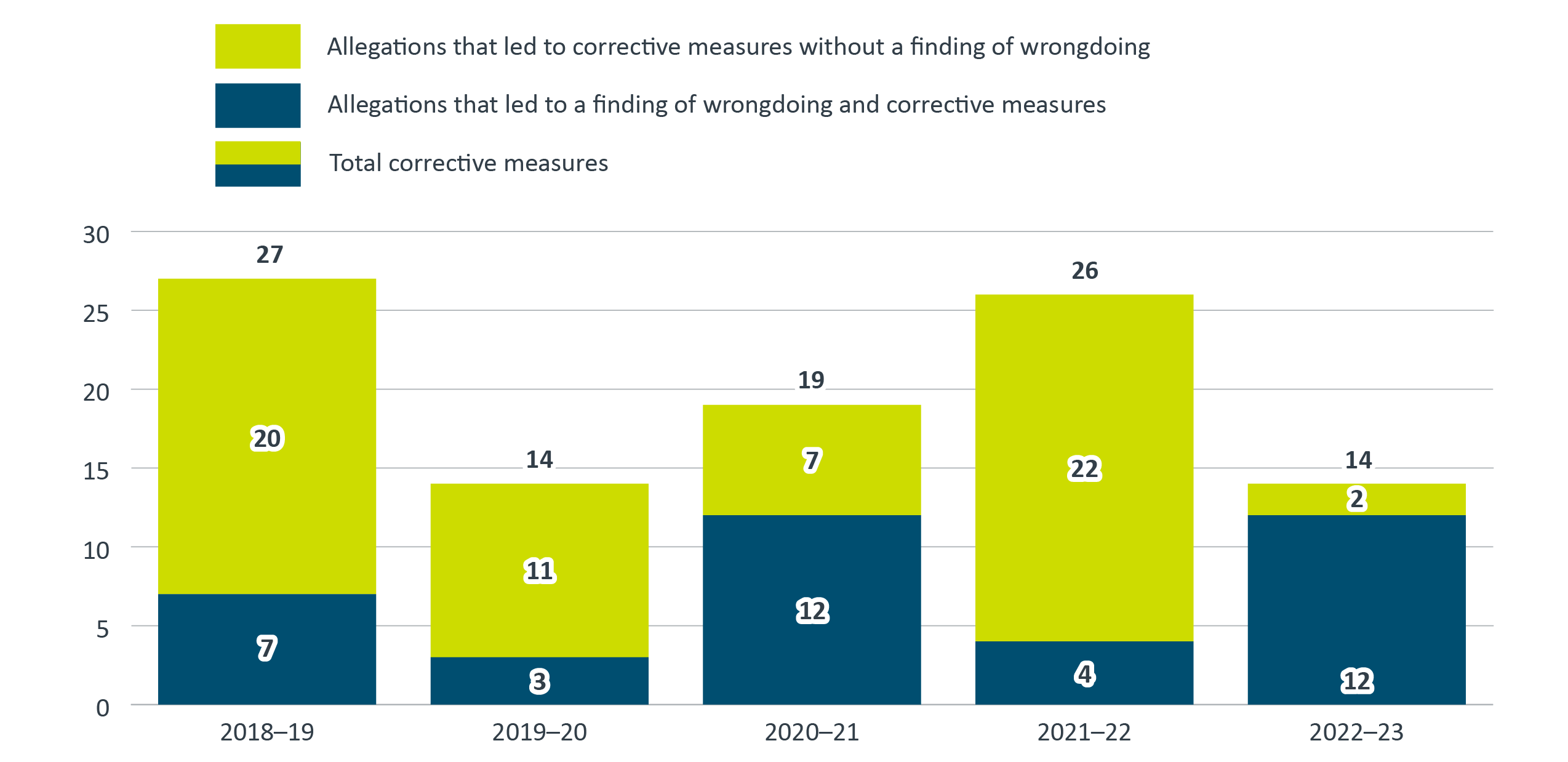

Step 4: findings of wrongdoing and corrective measures

In 2022–23, the 20 formal investigations that were closed by March 31, 2023, examined 50 allegations and resulted in 21 allegations that led to a finding of wrongdoing and 14 allegations that led to corrective measures (see Figure 8).Footnote 3 For two of the allegations that led to corrective measures, no wrongdoing was found. Twelve allegations of wrongdoing led to both a finding of wrongdoing and corrective measures.

In 2022–23, there were fewer formal investigations launched and fewer investigations closed than in the previous fiscal year.

Figure 8 - Text version

| Type | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | 2021–22 | 2022–23 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allegations that led to a finding of wrongdoing and corrective measures | 7 | 3 | 12 | 4 | 12 |

| Allegations that led to corrective measures without a finding of wrongdoing | 20 | 11 | 7 | 22 | 2 |

| Total corrective measures | 27 | 14 | 19 | 26 | 16 |

Education and awareness activities

Enterprise-wide

The Canada School of Public Service provides training to promote values and ethics in the workplace to all federal employees. Its courses include:

- “Values and Ethics Foundations for Employees” (FON301), which is mandatory for all new public servants

- “Values and Ethics Foundations for Managers” (FON302), which is mandatory for new supervisors and managers

Federal public sector organizations

Federal public sector organizations continue to raise awareness among public servants to inform them of:

- their organization’s code of conduct

- disclosure processes

- ways to support public servants who want to make disclosures of wrongdoing

There were many awareness activities conducted in 2022–23. For example, organizations provided training and other related activities to create awareness of the Act, its provisions and the protections that it provides. Those activities included training videos, town hall meetings, email messages, games, presentations and awareness sessions to inform employees about the Act and to foster an ethical workplace culture.

Organizations also held collaborative meetings among units and divisions within organizations to ensure that employees are aware of recourse mechanisms and initiatives. Such initiatives helped employees understand that there is “no wrong door,” meaning that their enquiry will be referred to appropriate channels. Other training helped to:

- identify and mitigate ethical risks

- improve awareness of codes of conduct, policies, procedures and processes

Organizations also undertook to develop or redesign policies for the internal disclosure of wrongdoing and update their internal procedures for handling disclosures of wrongdoing.

These types of deliberate and ongoing activities are integral to a healthy disclosure system. Employee awareness and promotional activities, including the important role the senior officer for internal disclosure plays in helping employees feel comfortable reporting wrongdoing without fearing reprisal, help to build trust. Trust in the senior officer and the organization is essential for maintaining confidence in the public service, not only among employees, but also among Canadians in general.

Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer: activities to support ethical workplaces

The Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer (OCHRO) acts as the focal point for driving people management excellence across the federal public service. As part of this mandate, it develops and disseminates policies, guidelines, initiatives and guidance in the areas of integrity and ethics in order to promote an ethical and healthy workplace. As it pertains to this report, the policies, programs and initiatives of OCHRO that are described below all contribute to fostering a workplace environment where public servants:

- are aware of the resources available for addressing workplace issues

- feel comfortable coming forward with enquiries or allegations of possible wrongdoing

Public Service Employee Survey: ethics in the workplace

To inform, support and strengthen people management in the federal public service and other practices in government,Footnote 4 OCHRO conducts the Public Service Employee Survey (PSES) every two years. A total of 189,584 employees in 90 federal departments and agencies responded to the most recent PSES, which gathered responses from November 21, 2022, to February 5, 2023.

The PSES includes questions that gauge public servants’ perceptions of the ethical environment in their workplace, and its results provide insights into how equipped public servants are to address values and ethical dilemmas. Results of the questions on ethics were analyzed by disaggregating the data by:

- employment equity group

- racial group

- province and territory

- employment community

- organizational mandate

Key results related to values and ethics in the workplace from the 2022 PSES

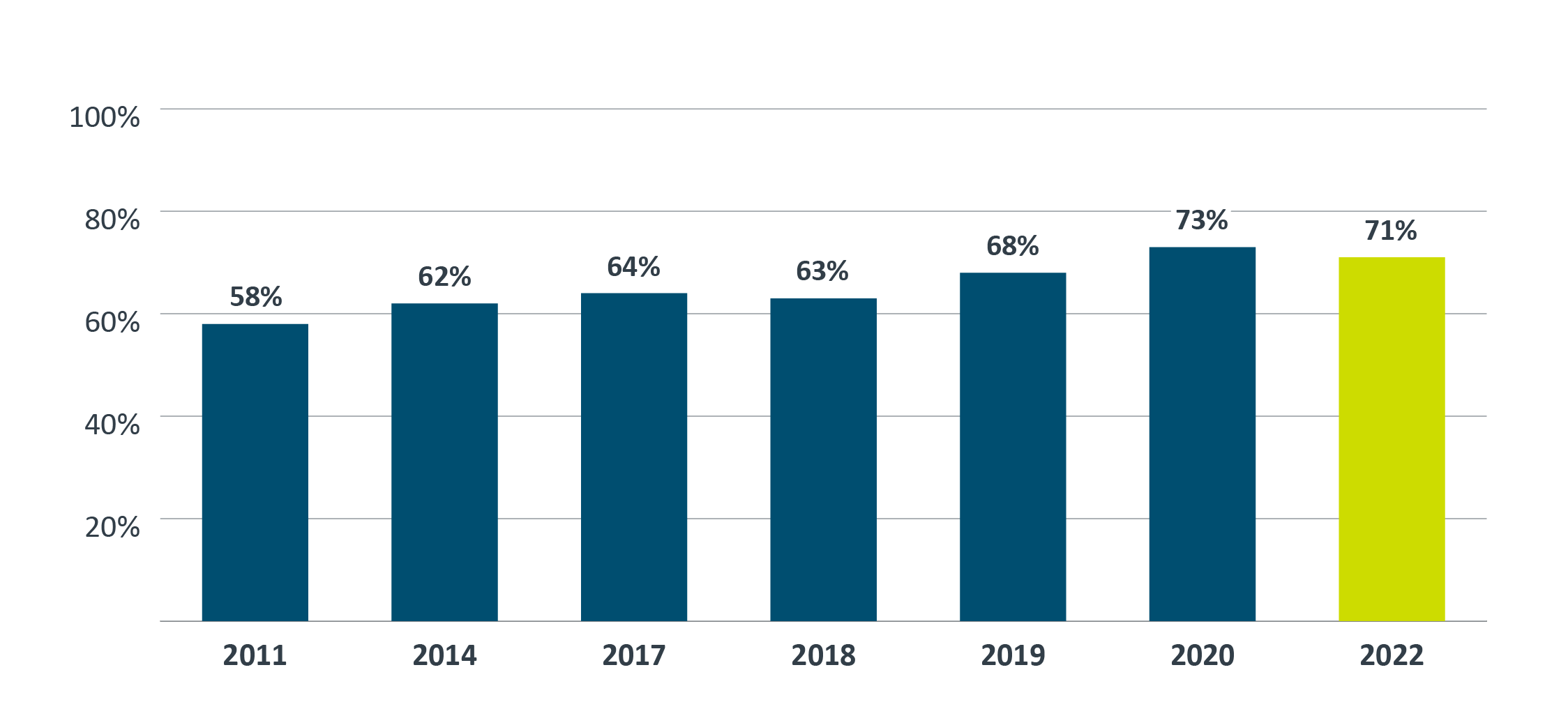

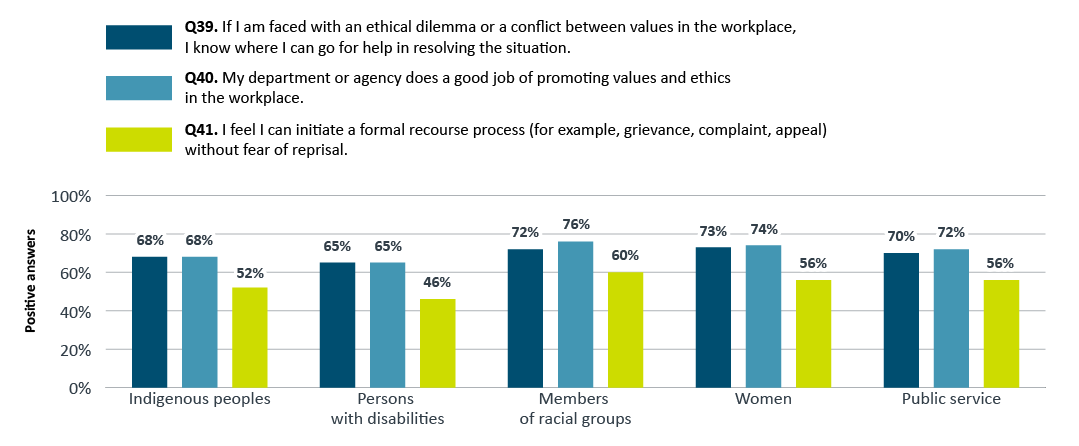

- 71% of public servants indicated that senior managers in their department or agency lead by example in ethical behaviour. Since 2011, public servants’ perception of ethical behaviour among their senior managers has improved by 13%.

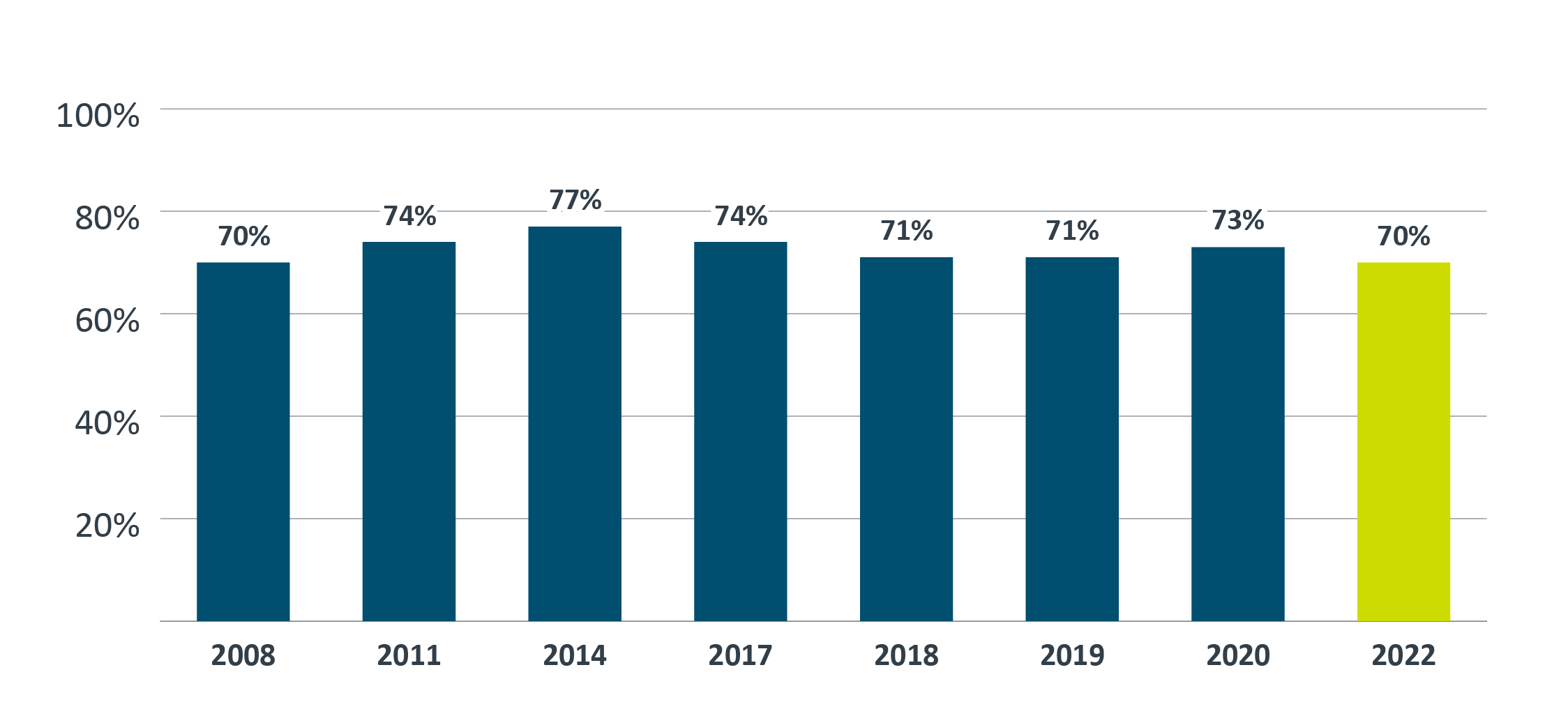

- 70% of public servants indicated that they would know where to go for help in resolving a situation if faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace. This indicator reached a peak of 77% in 2014.

- 72% of public servants indicated that they felt that their department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace. Across the provinces and regions, a lower percentage of public servants in the Northwest Territories, Saskatchewan, British Columbia and Alberta feel that their department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace.

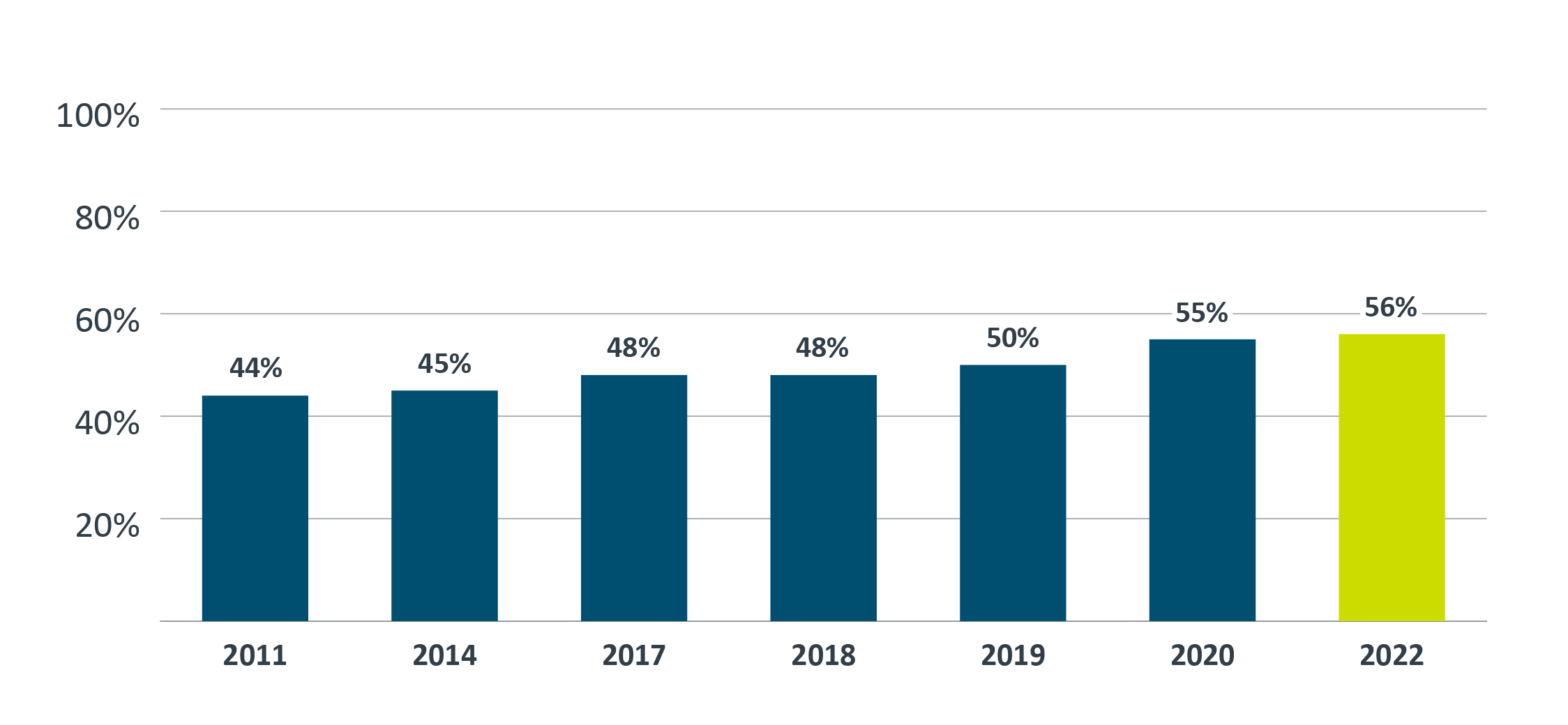

- 56% of public servants indicated that they felt they could initiate a formal recourse process (for example, grievance, complaint or appeal) without fear of reprisal. This indicator has been slow to increase, which indicates that there is significant room for improvement, especially among some demographic groups. For example, 46% of people with disabilities were confident that they could initiate a formal recourse process without fear of reprisal.

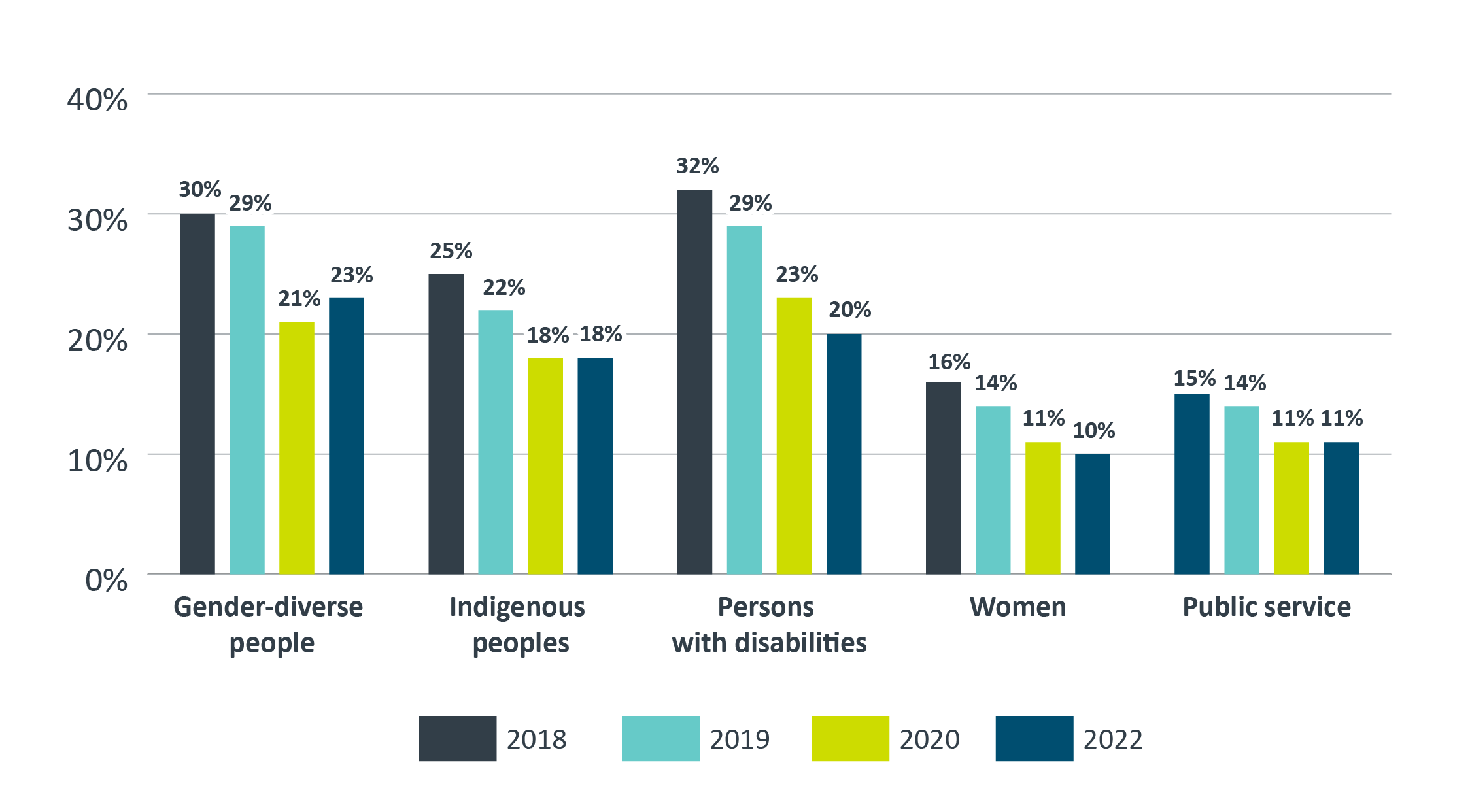

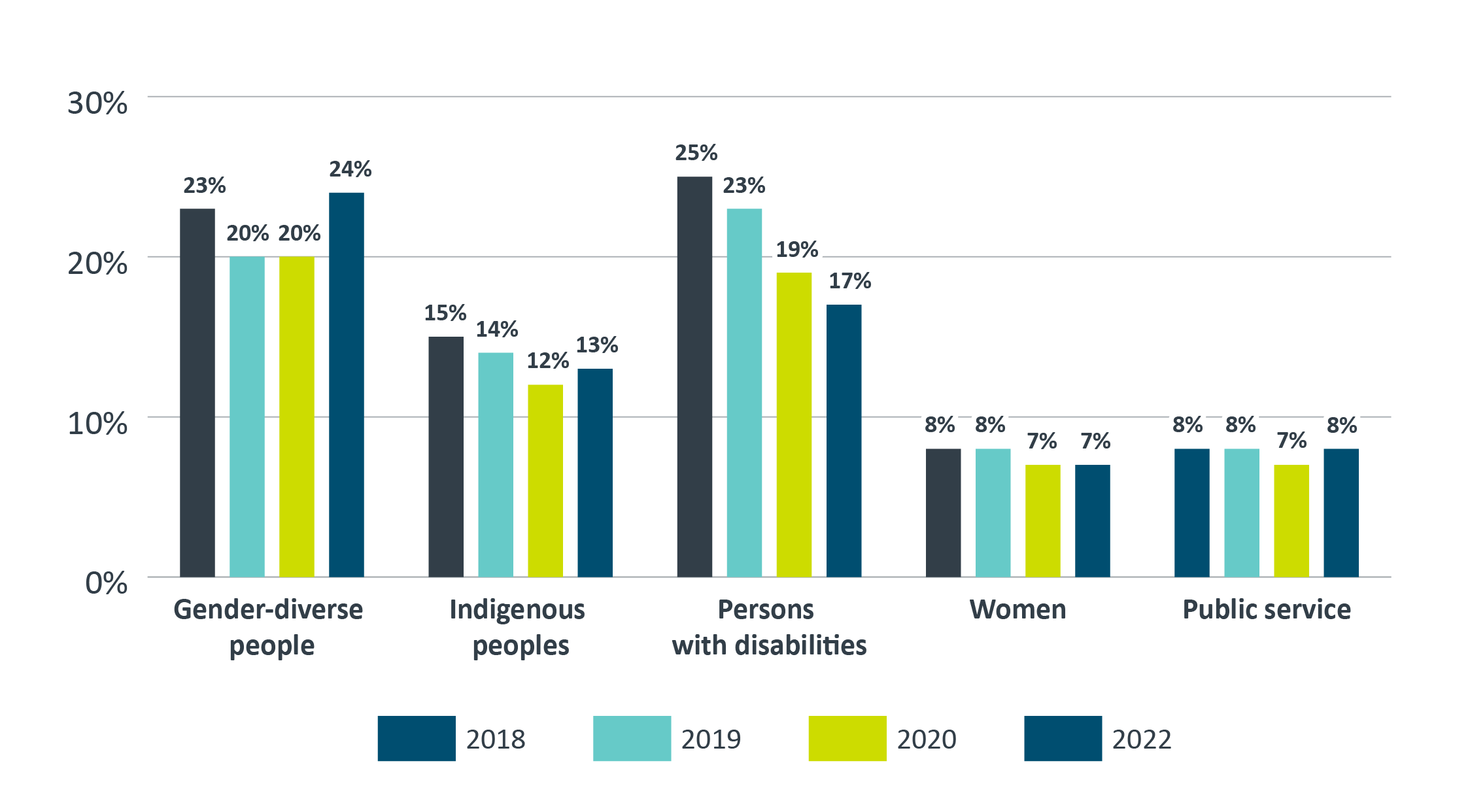

- Disaggregated results show that, like results in 2020, employees who self-identify as a person with a disability, an Indigenous person or as being gender-diverse reported experiencing double the rates of harassment compared with results for the public service as a whole. They also reported experiencing double to almost triple the rates of discrimination compared with results for the public service as a whole.

- Although mental health factors extend beyond values and ethics in the workplace, conditions that support mental health and wellness generate engagement and strengthen the confidence of employees to come forward with concerns about wrongdoing. Starting with the 2022 PSES, public servants were asked to comment on their mental health. Seventy-five per cent responded with either “good” or “better”, while 25%, rated their mental health as either “fair” or “poor.”

- Of employees who either strongly agreed or somewhat agreed with the statement that they would be comfortable with voicing concerns about mental health with the immediate supervisor, there was a slight improvement from 69% in 2020 to 73% in 2022.

Appendix B provides further details on PSES results on ethics in the workplace.

Diversity and inclusion in the workplace

A public service that is diverse, equitable and inclusive is essential for a workplace culture where all public servants, including employees from equity-seeking groups, can feel comfortable disclosing wrongdoing. To improve workplace culture and create culturally safe workplaces where employees feel comfortable disclosing wrongdoing, OCHRO advanced efforts to promote diversity and inclusion in 2022–23. Initiatives and activities included

- providing support to the task force for modernizing the Employment Equity Act

- collaboration between the Centre on Diversity and Inclusion and the employment equity networks to co-develop solutions for recruitment and talent management across the federal public service, including:

- the Designated Senior Officials for Employment Equity, Diversity and Inclusion community of practice

- the Employment Equity Champions and Chairs Committees and Circle

- other stakeholders

- leading initiatives to improve employment equity recruitment, data evidence and progress measurement; some notable projects include:

- Mentorship Plus to better support leadership development

- the Federal Speakers’ Forum on Lived Experience

- the Mosaic Leadership Development program

- the initiative to modernize the self-identification questionnaire

- web content on career pathways for Indigenous employees

Preventing and resolving harassment and violence in the workplace

A workplace that is free of violence and harassment is crucial to enable public servants to come forward with enquiries or allegations about possible wrongdoing without fear of reprisal. OCHRO remains committed to preventing and addressing incidences of workplace harassment and violence by providing continuous support to organizations in applying the Canada Labour Code, Work Place Harassment and Violence Prevention Regulations and Directive on the Prevention and Resolution of Workplace Harassment and Violence to:

- prevent occurrences

- provide a timely response

- support resolution of issues

- support employees affected by harassment and violence

OCHRO continues to engage with the Communities of Practice of Occupational Health and Safety Designated Recipients by:

- responding to enquiries

- providing advice and guidance

- applying the directive and regulations

- organizing knowledge transfer discussions

- participating in learning events across the public service

- leading the development of training and tools

OCHRO continues to consult with key stakeholders, including bargaining agents, to prevent workplace harassment and violence and to develop supporting tools and guidance to ensure that psychological health and safety have been integrated and remain at the forefront of OCHRO’s policy instruments to mitigate and prevent occupational illness and injury.

Mental health in the workplace

Having the right workplace conditions to support mental health and wellness generates higher levels of employee engagement and enhances public servants’ confidence in coming forward with concerns about wrongdoing. To support a culture of positive mental health in the workplace, OCHRO is:

- engaged in work to support federal organizations in aligning with the National Standard for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace and advancing the Federal Public Service Workplace Mental Health Strategy

- developing mental health resources for public servants, including a workplace mental health dashboard, to support organizational performance on the psychosocial risk factors of the National Standard for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace

Senior officers and communities of practice

It is also OCHRO’s role to:

- support the implementation and administration of the Act, the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector and conflict of interest measures

- support the President of the Treasury Board in their responsibility under the Act to promote ethical practices across the public sector

OCHRO’s policy centre engages with:

- the Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner

- the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Tribunal

- public sector organizations

- senior officers

- international organizations

- bargaining agents

- other stakeholders with an interest in integrity and ethics in the workplace

In particular, OCHRO facilitates a government-wide community of practice to support senior officers in internal disclosure of wrongdoing and managers in supporting public servants in their organizations. This community of practice provides an opportunity for sharing strategies and recent developments in the fields of:

- values and ethics

- disclosure of wrongdoing

- reprisal protection

- conflict of interest resolution

The community of practice activities include hosting meetings of the Internal Disclosure Working Group and the Interdepartmental Network of Values and Ethics practitioners. These meetings allow for discussion and collaboration on:

- managing a healthy workplace culture

- ethical leadership

- managing ethical risks

- promoting integrity within the public sector

International engagement

In 2022–23, OCHRO continued to collaborate with international bodies and organizations to promote global integrity and address corruption. Through these international engagements, OCHRO stays updated and involved in global activities, research and sharing of knowledge on integrity, accountability, anti-corruption, and best practices on disclosure regimes around the world. OCHRO’s involvement also allows for promoting Canada’s practices, approaches and strategies. International engagements that occurred during the 2022–23 fiscal year included Canada’s participation in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Working Party of Senior Public Integrity Officials, through which OCHRO contributes to strengthening public sector governance and safeguarding the integrity of public policy-making.

Appendix A: Summary of Disclosure-Related Organizational Activities

Subsection 38.1(1) of the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (the Act) requires chief executives to prepare a report on the activities related to disclosures made in their organizations and to submit it to the Chief Human Resources Officer within 60 days of the end of each fiscal year. The information and statistics in this report are based on those reports.

In the sections that follow, statistics from the previous four fiscal years are also provided to allow for comparison. Although these statistics provide a snapshot of internal disclosure activities under the Act, it is difficult to draw conclusions because of the variety of organizational cultures within the public sector. For example, employee concerns or issues may be referred through different recourse mechanisms and processes in different organizations.

Although the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), Communications Security Establishment Canada (CSEC) and Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) are excluded from the Act by virtue of section 52, they are required to establish their own procedures for the disclosure of wrongdoing, including for protecting persons who disclose wrongdoing. The Treasury Board must approve these procedures as being similar to those set out in the Act. CSIS’s procedures were approved in December 2009, CSEC’s procedures were approved in June 2011, and the CAF’s procedures were approved in April 2012.

A.1 Disclosure activity from 2018–19 to 2022–23

| General enquiries | 2022-23 | 2021-22 | 2020-21 | 2019-20 | 2018-19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of general enquiries related to the Act | 315 | 384 | 172 | 250 | 323 |

| Disclosure activity | 2022-23 | 2021-22 | 2020-21 | 2019-20 | 2018-19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of public servants who made disclosures | 152 | 194 | 123 | Not applicable |

Not applicable |

| Number of disclosures received | 246 | 178 | 101 | Not applicable |

Not applicable |

| Number of allegations received in disclosures under the Act | 356 | 378 | 169 | 216 | 269 |

| Number of allegations of wrongdoing received resulting from a disclosure made in another public sector organization | 9 | 3 | 5 | 4 | 3 |

| Number of allegations carried over from previous fiscal years | 277 | 160 | 192 | 238 | 173 |

| Total number of allegations handled (allegations received, including those resulting from a disclosure made in another public sector organization and carried over) | 633 | 541 | 366 | 458 | 445 |

| Number of allegations that met the definition of wrongdoing | 323 | 190 | 111 | 116 | 114 |

| Number of allegations that did not meet the definition of wrongdoing or were referred to another recourse process | 81 | 154 | 76 | 164 | 129 |

| Number of investigations commenced as a result of disclosures received | 50 | 85 | 63 | 38 | 59 |

| Number of allegations that led to a finding of wrongdoing | 21 | 5 | 12 | 3 | 7 |

| Number of allegations that led to corrective measures | 14 | 26 | 19 | 11 | 20 |

| Number of allegations that led to a finding of wrongdoing and corrective measures | 12 | 4 | 12 | 3 | 7 |

Notes Disclosures that met the definition of wrongdoing are those for which action, including preliminary analysis, fact-finding and investigation, was taken to determine whether wrongdoing occurred and when that determination was made during the reporting period. Disclosures that did not meet the definition of wrongdoing are those for which the designated senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing determined that the definition of wrongdoing under the Act was not met or had to be referred to another process or required no further action. |

|||||

| Organizations reporting | 2022-23 | 2021-22 | 2020-21 | 2019-20 | 2018-19 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of organizations | 135 | 136 | 137 | 133 | 134 |

| Number of organizations that reported enquiries | 38 | 35 | 30 | 33 | 35 |

| Number of organizations that reported allegations received in disclosures | 29 | 29 | 27 | 24 | 29 |

| Number of organizations that reported findings of wrongdoing | 7 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Number of organizations that reported corrective measures | 7 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 8 |

| Number of organizations that reported finding systemic problems that gave rise to wrongdoing | 4 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 |

| Number of organizations that did not disclose information about findings of wrongdoing within 60 days | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

A.2 Organizations reporting activity under the Act in 2022–23

| Allegations received in disclosures | Investigations commenced | Allegations received in disclosures that led to | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General enquiries | Received | Carried over from the 2021–22 fiscal year | Acted upon | Not acted upon | Referred | Carried over into the 2023–24 fiscal year | Corrective measures | Finding of wrongdoing | ||

| Accessibility Standards Canada | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Atomic Energy of Canada Limited | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada Border Services Agency | 14 | 15 | 116 | 51 | 0 | 0 | 80 | 7 | 4 | 4 |

| Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada Post Corporation | 0 | 146 | 0 | 146 | 0 | 22 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Canada Revenue Agency | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada School of Public Service | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canadian Food Inspection Agency | 2 | 12 | 0 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canadian Grain Commission | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canadian Heritage (Department of Canadian Heritage) | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canadian Museum of Nature | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Correctional Service Canada | 31 | 37 | 2 | 34 | 5 | 2 | 34 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Department of Finance | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Department of Fisheries and Oceans | 4 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Department of Justice | 4 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Department of National Defence | 17 | 1 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Department of Transport | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Department of Veterans Affairs and Veterans Review and Appeal Board (one report for both) | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada (including Service Canada, Labour Program, and Canada Employment Insurance Commission) | 40 | 23 | 8 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 23 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | 3 | 5 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Export Development Canada | 14 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Farm Credit Canada | 0 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Global Affairs Canada | 26 | 29 | 86 | 13 | 28 | 8 | 60 | 13 | 0 | 2 |

| Health Canada | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indigenous Services Canada | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development, and Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy | 4 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| International Development Research Centre | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Natural Resources Canada | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| National Capital Commission | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| National Research Council Canada | 3 | 1 | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| National Security Intelligence Review Agency | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Parks Canada Agency | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Parole Board of Canada | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Privy Council Office | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada | 2 | 10 | 42 | 9 | 5 | 5 | 32 | 13 | 0 | 7 |

| Royal Canadian Mint | 1 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police | 28 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Shared Services Canada | 4 | 4 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Staff of the Non-Public Funds, Canadian Forces | 7 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Standards Council of Canada | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Statistics Canada | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| VIA Rail Canada Inc. | 70 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 315 | 356 | 277Footnote 5 | 323 | 81 | 64 | 253 | 50 | 14 | 21 |

A.3 Organizations that reported a finding of wrongdoing under the Act, 2022–23Footnote 6

| Organization | Finding of wrongdoing | Corrective measures |

|---|---|---|

| Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) | A gross mismanagement in the public sector; a serious breach of a code of conduct established under section 5 or 6 Case report: Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: Reference Number CBSA-FW-2021-Q3-00001 |

An investigation determined that a chief and a superintendent at a port of entry committed serious breaches of the CBSA Code of Conduct whose cumulative effect constituted gross mismanagement. The superintendent was found to have harassed staff over several years through aggressive and abusive behaviour, vulgar remarks, and sexual harassment. The chief demonstrated a failure in leadership by not taking appropriate action, over an extended period, to deal with the unacceptable conduct of the superintendent. This resulted in a harmful effect on the work environment at the port of entry. The Senior Officer of Internal Disclosure (SOID) recommended that the CBSA implement corrective measures and disciplinary actions guided by the quantum of discipline. The SOID further recommended that the CBSA consider the need for training in management, leadership, harassment and workplace violence for the chief or more broadly as determined to be appropriate. Finally, the SOID recommended that the appropriate actions be taken to repair and restore the work environment at the port of entry. The superintendent resigned prior to the investigation’s conclusion. The President of the CBSA accepted the recommendations of the SOID. Actions are being taken by the CBSA to implement appropriate corrective measures and disciplinary actions. |

| National Defence | Case report: Founded Disclosures of Wrongdoing (see “Founded Wrongdoings for Fiscal Year 2017/18") |

An investigation determined that payments were being made in a manner that raised legal liability concerns and that the former Base Commander had engaged in acts that constituted a misuse of public funds and a breach of government contracting regulations. It was recommended that the payment agreement be cancelled and that a formal contract be put in place to obtain the transportation services required for National Defence and Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) members and their families. It was also recommended that the current Base Commander, along with representatives from Military Personnel Command:

|

| Transport Canada | Former senior executives within the Human Resources Directorate committed wrongdoing as defined under paragraphs 8(c) and 8(e) of the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act, specifically, gross mismanagement and a serious breach of the code of conduct. Case report: Published Findings and Management Action Plan – Staffing and Classification |

It was determined that actions of the individuals investigated went against people management policies by inappropriately staffing and classifying positions. Their actions, which included ignoring expert advice, created a culture where staff felt they could not speak about their concerns without fear of being marginalized and excluded. The senior executives who were the subject of this investigation are no longer with the department, and the current executive team within the Human Resources Directorate has changed. It was recommended that the Assistant Deputy Minister, Corporate Services, seek independent advice as required to promptly address complaints and grievances from Human Resources Directorate employees or should questions be raised concerning Human Resources Directorate staffing, classification or pay actions. It was also recommended that the Assistant Deputy Minister, Corporate Services, continue to closely monitor the Human Resources Directorate workplace and request a neutral third-party intervention as required should issues be brought to their attention. |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | A misuse of public funds or a public asset Case report: Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: Reference Number FW-2022-Q2-00001 |

An investigation determined that that an employee misused public assets by making personal use of Crown property and misused public funds by using departmental contracted services for personal ends. The public servant took retirement from the public service prior to the conclusion of the investigation. It was recommended that:

|

Global Affairs Canada |

An act or omission that creates a substantial and specific danger to the life, health or safety of persons, or to the environment, other than a danger that is inherent in the performance of the duties or functions of a public servant; a serious breach of a code of conduct established under section 5 or 6 Case report: Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: Reference Number PSDPA-2021-0010 |

An investigation determined that an employee had committed wrongdoing pursuant to paragraphs 8.d) and e) of the Act; that is, an act or omission that creates a substantial and specific danger to the life, health or safety of persons and a serious breach of a code of conduct. The investigation found that the employee behaved inappropriately, made inappropriate comments, and bullied and harassed his subordinates. The investigation also found that this employee engaged in repeated unwanted touching and aggressive romantic pursuit of female personnel while they were on duty. These actions constitute a serious breach of the Departmental Value and Ethics Code as it relates to the values of respect for people and Integrity. The employee is no longer working for Global Affairs Canada. The department also took actions to restore the work environment within the affected group and provided outreach and assistance to those who were affected by the actions of the former employee. |

A gross mismanagement in the public sector; a serious breach of a code of conduct established under section 5 or 6 Case report: Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: Reference Number PSDPA2020-0017 |

An investigation found that a departmental senior official condoned their spouse’s behaviour when formally appraising an Official Residence employee as not meeting work objectives, partly on the basis that the employee did not perform the additional personal domestic services to the level expected. It was determined that the cumulative effect constituted gross mismanagement in the public sector. The senior officer for internal disclosure recommended that a disciplinary process be conducted to address the founded wrongdoings, and corrective measures have been taken accordingly. |

|

| National Research Council Canada (NRC) | A misuse of public funds or a public asset and a serious breach of a code of conduct established under section 5 or 6 Case report: Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: Reference Number 2021-PSDPA-01 |

An investigation found that a senior researcher and team leader engaged in a misuse of public funds and serious breaches of the NRC Code of Conduct. The employee was found to have been in a conflict of interest with a team member and failed to report and resolve the conflict. The senior officer for internal disclosure recommended that a disciplinary process be conducted to address the founded wrongdoings, and corrective measures have been taken accordingly, and the NRC is reviewing its procedures and oversight mechanisms for the negotiation of collaboration agreements with outside entities and the valuation of in-kind contributions from the NRC. |

Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) |

A serious breach of a code of conduct established under section 5 or 6 Case report: Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: Reference Number: SIID-2019-047 |

An investigation found that an employee to whom appointment and related powers had been sub-delegated:

The employee breached these basic requirements as part of their terms of employment. Senior management accepted their resignation. |

A serious breach of a code of conduct established under section 5 or 6 Case report: Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: Reference Number: 2021-2022-001 |

An investigation found that an employee:

This employee and the individual who was hired both failed in their obligations to avoid, declare and recuse themselves from the conflict-of-interest situation. The wrongdoing constituted serious breaches of the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector, the PSPC Code of Conduct and PSPC’s guideline on conflict of interest arising from family and personal relationships. The term employee was terminated while on probation; the other employee was subject to a period of suspension without pay. |

|

A serious breach of a code of conduct established under section 5 or 6 Case reports: Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: Reference Number SIID-2020/21-001 and Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: Reference Number 2020-2021-003 |

Investigations found that employees with sub-delegation for staffing appointments and decisions placed themselves in a conflict of interest by promoting, participating, influencing and/or exercising staffing sub-delegation in processes leading to the hiring of parents as casual and indeterminate employees. The employees failed to take steps to disclose, avoid and recuse themselves from the conflict of interest and failed to comply with instructions issued to them by PSPC, which were designed to prevent and avoid any conflict of interest in staffing activities. The employees failed in these fundamental requirements forming part of their terms and conditions of employment and, as a result, disciplinary measure against the employees have been taken. The employees no longer work for PSPC. |

A.4 Organizations that reported no disclosure activities in 2022–23

- Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency

- Atlantic Pilotage Authority Canada

- Bank of Canada

- Business Development Bank of Canada

- Canada Council for the Arts

- Canada Development Investment Corporation

- Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions

- Canada Energy Regulator (previously National Energy Board)

- Canada Infrastructure Bank

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation

- Canada Pension Plan Investment Board

- Canada Science and Technology Museum

- Canadian Air Transport Security Authority

- Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) / Radio-Canada

- Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety

- Canadian Commercial Corporation

- Canadian Human Rights Commission

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- Canadian Museum for Human Rights

- Canadian Museum of History and Canadian War Museum

- Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency

- Canadian Space Agency

- Canadian Transportation Agency

- Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- Correctional Investigator Canada, The

- Courts Administration Service

- Defence Construction Canada

- Destination Canada

- Elections Canada

- Farm Products Council of Canada

- Federal Bridge Corporation Limited, The

- Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario

- Financial Consumer Agency of Canada

- Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada

- Great Lakes Pilotage Authority Canada

- Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada

- Impact Assessment Agency of Canada

- Indian Oil and Gas Canada

- Infrastructure Canada

- International Joint Commission (Canadian Section)

- Invest in Canada Hub

- Laurentian Pilotage Authority Canada

- Library and Archives Canada

- Marine Atlantic Inc.

- Military Police Complaints Commission of Canada

- National Arts Centre Corporation

- National Battlefields Commission, The

- National Gallery of Canada

- Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada

- Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs Canada

- Office of the Director of Public Prosecutions

- Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada

- Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada

- Office of the Secretary of the Governor General

- Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada

- Pacific Economic Development Canada

- Pacific Pilotage Authority Canada

- Patented Medicine Prices Review Board Canada

- Prairies Economic Development Canada

- Public Prosecution Service of Canada

- Public Safety Canada

- Public Sector Pension Investment Board

- Public Service Commission of Canada

- Seaway International Bridge Corporation

- Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada

- Statistical Survey Operations

- Supreme Court of Canada

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

- Women and Gender Equality Canada

A.5 Organizations that do not have a senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing that declared an exception under subsection 10.4 of the Act

- Administrative Tribunal Support Services of Canada

- Canada Lands Company Limited

- Canadian Dairy Commission

- Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat

- Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21

- Canadian Race Relations Foundation

- Copyright Board Canada

- Freshwater Fish Marketing Corporation

- Military Grievances External Review Committee

- National Film Board

- Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages

- Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

- Polar Knowledge Canada

- RCMP External Review Committee

- Telefilm Canada

- Transportation Safety Board of Canada

Appendix B: Public Service Employee Survey – Ethics in the Workplace

The data presented in this appendix is sourced from the 2022 Public Service Employee Survey (PSES) results for the public service.Footnote 7

Figure B1 - Text version

| Survey years | Postive answers |

|---|---|

| 2011 | 58% |

| 2014 | 62% |

| 2017 | 64% |

| 2018 | 63% |

| 2019 | 68% |

| 2020 | 73% |

| 2022 | 71% |

Figure B2 - Text version

| Survey years | Postive answers |

|---|---|

| 2008 | 70% |

| 2011 | 74% |

| 2014 | 77% |

| 2017 | 74% |

| 2018 | 71% |

| 2019 | 71% |

| 2020 | 73% |

| 2022 | 70% |

Figure B3 - Text version

| Survey years | Postive answers |

|---|---|

| 2018 | 69% |

| 2019 | 69% |

| 2020 | 74% |

| 2022 | 72% |

Figure B4 - Text version

| Survey years | Postive answers |

|---|---|

| 2011 | 44% |

| 2014 | 45% |

| 2017 | 48% |

| 2018 | 48% |

| 2019 | 50% |

| 2020 | 55% |

| 2022 | 56% |

Figure B5 - Text version

- Q39. If I am faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace, I know where I can go for help in resolving the situation.

- Q40. My department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace.

- Q41. I feel I can initiate a formal recourse process (for example, grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal.

| Question | Indigenous peoples | Persons with disabilities | Members of racial group | Women | Public service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q39 | 68% | 65% | 72% | 73% | 70% |

| Q40 | 68% | 65% | 76% | 74% | 72% |

| Q41 | 52% | 46% | 60% | 56% | 56% |

Table B1: percentages of positive answers to three questions in the 2022 PSES, by province, territory and the National Capital Region

| Provinces, territory or National Capital Region | Q39. If I am faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace, I know where I can go for help in resolving the situation (%) | Q40. My department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace (%) | Q41. I feel I can initiate a formal recourse process (for example, grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outside of Canada | 74 | 62 | 41 |

| Northwest Territories | 69 | 66 | 54 |

| Saskatchewan | 68 | 67 | 52 |

| British Columbia | 69 | 68 | 54 |

| Alberta | 69 | 69 | 54 |

| Yukon | 72 | 70 | 54 |

| Nova Scotia | 71 | 71 | 56 |

| Ontario (excluding National Capital Region) | 70 | 71 | 57 |

| Nunavut | 69 | 72 | 62 |

| Quebec (excluding National Capital Region) | 67 | 72 | 57 |

| Manitoba | 72 | 73 | 58 |

| National Capital Region | 71 | 73 | 54 |

| New Brunswick | 74 | 76 | 63 |

| Prince Edward Island | 75 | 77 | 63 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 79 | 83 | 67 |

Table B2: percentages of positive answers to three questions in the 2022 PSES, by organizational mandate and the public service overall

| Organizational mandate | Q39. If I am faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace, I know where I can go for help in resolving the situation (%) | Q40. My department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace (%) | Q41. I feel I can initiate a formal recourse process (for example, grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Other mandate | 68 | 61 | 42 |

| Security and Military | 63 | 60 | 50 |

| Business and Economic Development | 67 | 70 | 51 |

| Science-Based | 68 | 71 | 53 |

| Justice, Courts and Tribunals | 75 | 76 | 54 |

| Central Agency and Government Operations | 74 | 76 | 58 |

| Social and Culture | 74 | 77 | 59 |

| Agents of Parliament | 78 | 78 | 62 |

| Enforcement and Regulatory | 76 | 80 | 64 |

| Public service | 68 | 61 | 42 |

Table B3: percentages of positive answers to three questions in the 2022 PSES, by employment community

| Employment community | Q39. If I am faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace, I know where I can go for help in resolving the situation (%) | Q40. My department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace (%) | Q41. I feel I can initiate a formal recourse process (for example, grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Security | 53 | 48 | 40 |

| Health care practitioners | 64 | 62 | 47 |

| Policy | 67 | 68 | 47 |

| Legal services | 73 | 74 | 48 |

| Federal regulators | 71 | 70 | 51 |

| None of the above | 66 | 66 | 52 |

| Project management | 70 | 73 | 52 |

| Communications or public affairs | 69 | 72 | 54 |

| Compliance, inspection and enforcement | 68 | 69 | 54 |

| Science and technology | 66 | 71 | 54 |

| Real property | 68 | 70 | 55 |

| Evaluation | 71 | 74 | 57 |

| Other services to the public | 71 | 72 | 57 |

| Administration and operations | 74 | 75 | 58 |

| Financial management | 73 | 76 | 58 |

| Procurement | 73 | 77 | 58 |

| Data sciences | 67 | 73 | 59 |

| Information management | 72 | 74 | 59 |

| Materiel management | 69 | 71 | 59 |

| Human resources | 78 | 76 | 60 |

| Library services | 69 | 71 | 60 |

| Internal audit | 78 | 79 | 62 |

| Information technology | 73 | 77 | 63 |

| Access to information and privacy | 77 | 80 | 65 |

| Client contact centre | 77 | 82 | 67 |

Figure B6 - Text version

| Year | Gender-diverse people | Indigenous peoples | Persons with disabilities | Women | Public service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 30% | 25% | 32% | 16% | 15% |

| 2019 | 29% | 22% | 29% | 14% | 14% |

| 2020 | 21% | 18% | 23% | 11% | 11% |

| 2022 | 23% | 18% | 20% | 10% | 11% |

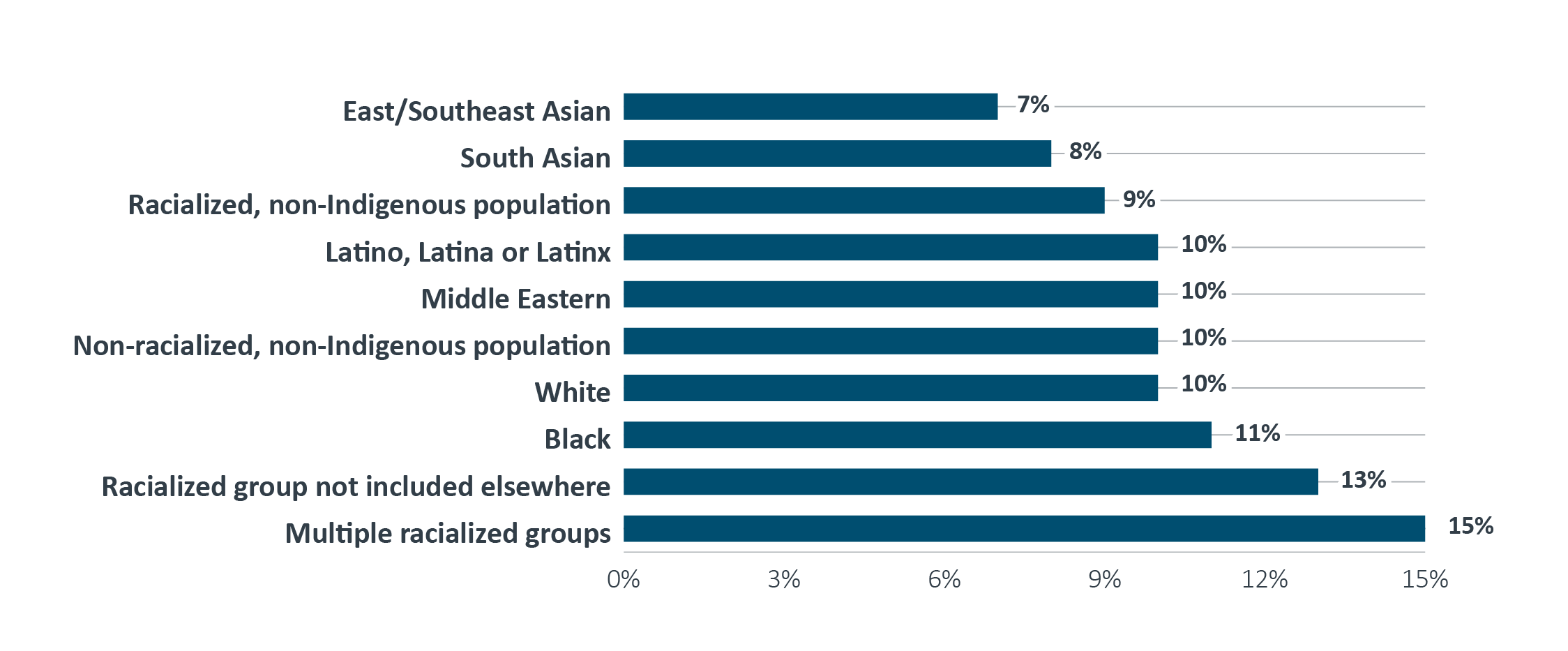

Figure B7 - Text version

| Racial Groups | Agree (%) |

|---|---|

| East/Southeast Asian | 7% |

| South Asian | 8% |

| Racialized, non-Indigenous population | 9% |

| Latino, Latina or Latinx | 10% |

| Middle Eastern | 10% |

| Non-racialized, non-Indigenous population | 10% |

| White | 10% |

| Black | 11% |

| Racialized group not included elsewhere | 13% |

| Multiple racialized groups | 15% |

Figure B8 - Text version

| Year | Gender-diverse people | Indigenous peoples | Persons with disabilities | Women | Public service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 23% | 15% | 25% | 8% | 8% |

| 2019 | 20% | 14% | 23% | 8% | 8% |

| 2020 | 20% | 12% | 19% | 7% | 7% |

| 2022 | 24% | 13% | 17% | 7% | 8% |

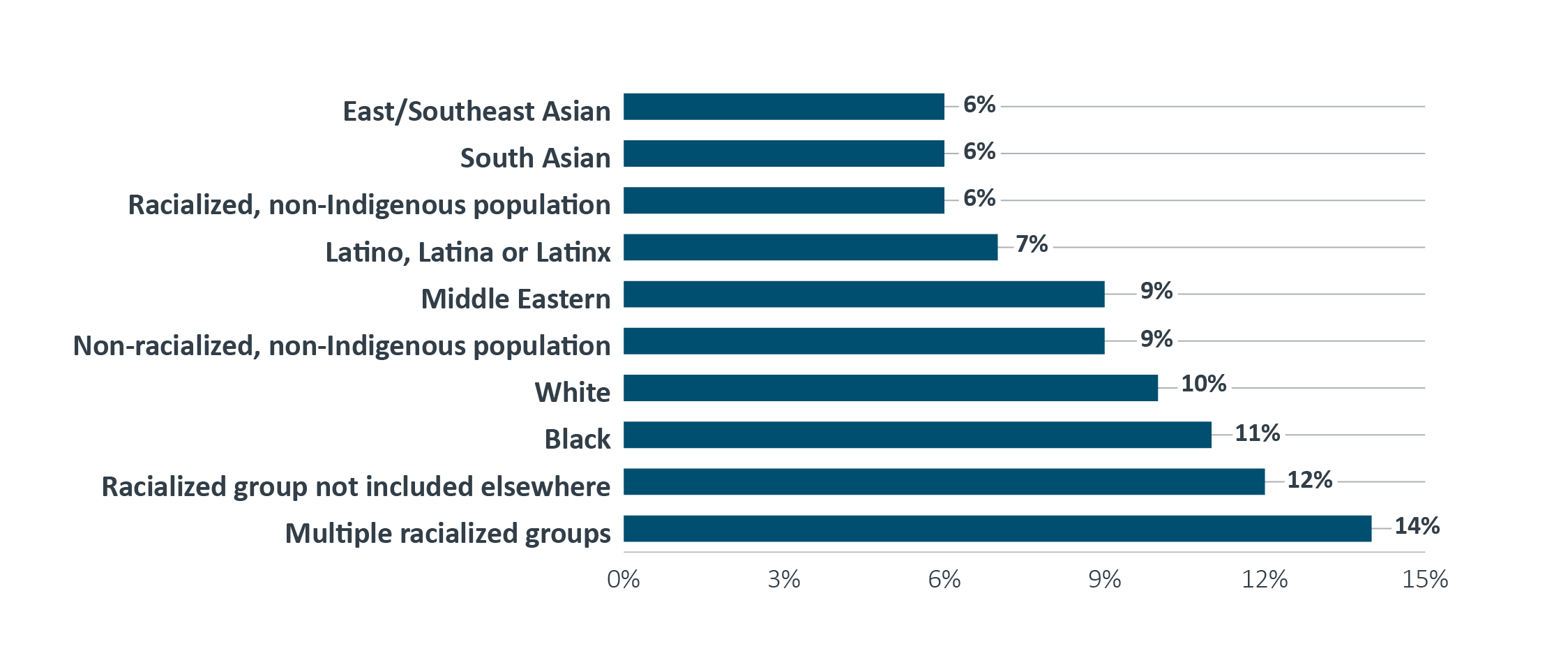

Figure B9 - Text version

| Racial Groups | Agree (%) |

|---|---|

| East/Southeast Asian | 6% |

| Non-racialized, non-Indigenous population | 6% |

| White | 6% |

| South Asian | 7% |

| Latino, Latina or Latinx | 9% |

| Racialized, non-Indigenous population | 9% |

| Middle Eastern | 10% |

| Black | 11% |

| Racialized group not included elsewhere | 12% |

| Multiple racialized groups | 14% |

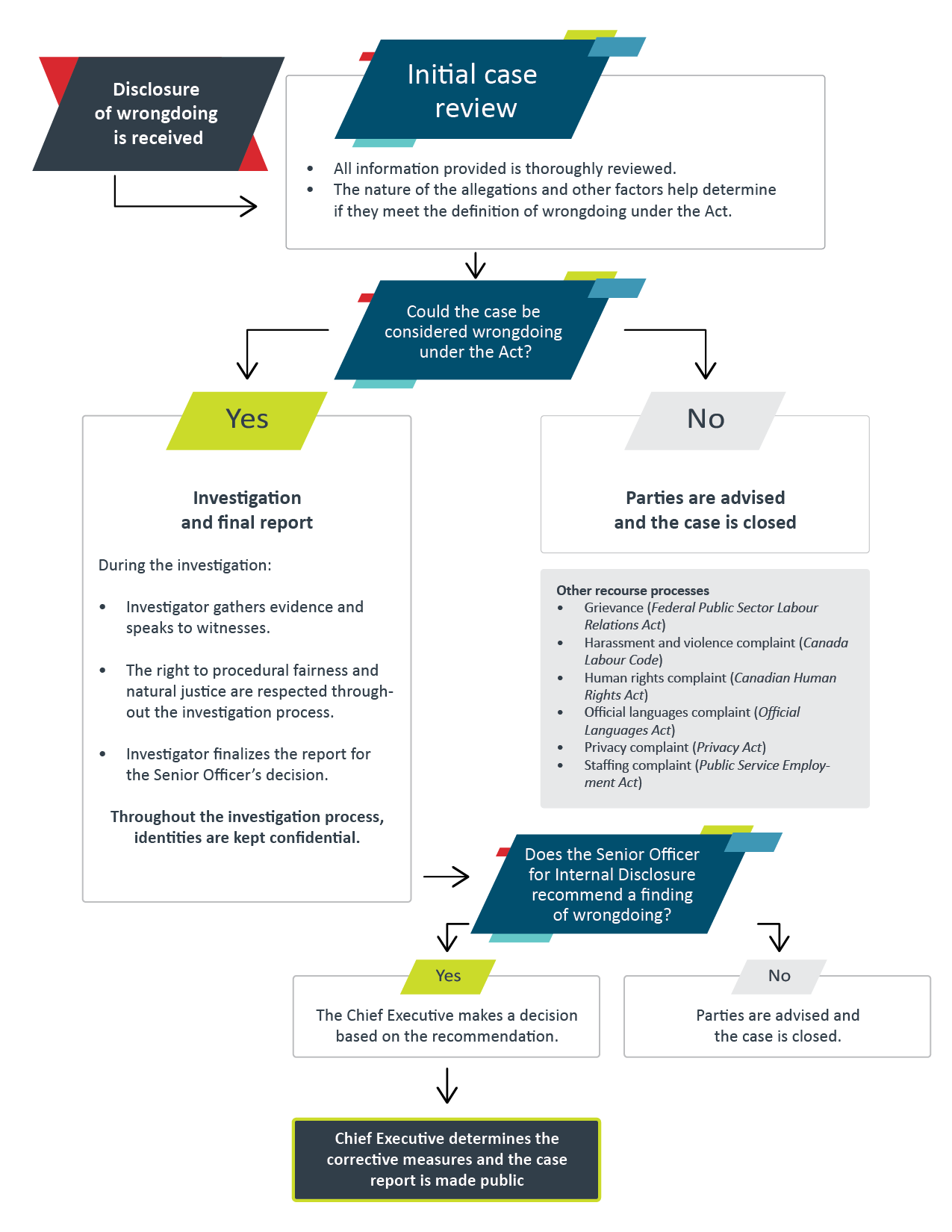

Appendix C: Disclosure Process Under the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act

Figure C1 - Text version

Disclosure of wrongdoing is received

Initial case review

- All information provided is thoroughly reviewed.

- The nature of the allegations and other factors help determine if they meet the definition of wrongdoing under the Act.

Could the case be considered wrongdoing under the Act?

Yes

Investigation and final report

During the investigation

- Investigator gathers evidence and speaks to witnesses.

- The right to procedural fairness and natural justice are respected throughout the investigation process.

- Investigator finalizes the report for the Senior Officer’s decision.

Throughout the investigation process, identities are kept confidential.

No

Parties are advised and the case is closed

Does the Senior Officer for Internal Disclosure recommend a finding of wrongdoing?

Yes

The Chief Executive makes a decision based on the recommendation

Chief Executive determines the corrective measures and the results are made public

No

Parties are advised and the case is closed.

Other recourse processes

- Harassment and violence complaint (Canada Labour Code)

- Human rights complaint (Canadian Human Rights Act)

- Grievance (Federal Public Sector Labour Relations Act)

- Staffing complaint (Public Service Employment Act)

- Official languages complaint (Official Languages Act)

- Privacy complaint (Privacy Act)

Appendix D: Key Terms

For the purposes of the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (the Act) and this report, “public servant” means every person employed in the public sector. The term includes the deputy heads and chief executives of public sector organizations, but it does not include other Governor in Council appointees (for example, judges or board members of Crown corporations) or parliamentarians and their staff.

The Act defines wrongdoing as any of the following actions in, or relating to, the public sector:

- a violation of a federal or provincial law or regulation

- a misuse of public funds or assets

- a gross mismanagement in the public sector

- a serious breach of a code of conduct established under the Act

- an act or omission that creates a substantial and specific danger to the life, health or safety of persons, or to the environment

- knowingly directing or counselling a person to commit a wrongdoing

A protected disclosure is a disclosure that is made in good faith by a public servant under any of the following conditions:

- in accordance with the Act, to the public servant’s immediate supervisor or senior officers for disclosure of wrongdoing, or to the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada

- in the course of a parliamentary proceeding

- in the course of a procedure established under any other act of Parliament

- when lawfully required to do so

The Act defines reprisal as any of the following measures taken against a public servant who has made a protected disclosure or who has, in good faith, cooperated in an investigation into a disclosure:

- a disciplinary measure

- demotion of the public servant

- termination of the employment of the public servant

- a measure that adversely affects the employment or working conditions of the public servant

- a threat to do any of the above or to direct a person to do them

Every organization subject to the Act is required to establish internal procedures to manage disclosures made in the organization. Organizations that are too small to establish their own internal procedures can declare an exception under subsection 10(4) of the Act. In addition, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, Communications Security Establishment Canada and Canadian Armed Forces, which are excluded from the Act by virtue of section 52 of the Act, are required to establish their own procedures for the disclosure of wrongdoing, including for protecting persons who disclose wrongdoing.

In organizations that have declared an exception, disclosures under the Act may be made to the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada

The senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing is the person designated in each organization to receive and address disclosures made under the Act. Senior officers have the following key leadership roles for implementing the Act in their organizations:

- providing information, advice and guidance to public servants regarding the organization’s internal disclosure procedures, including the making of disclosures, the conduct of investigations into disclosures, and the handling of disclosures made to supervisors

- receiving and recording disclosures and reviewing them to establish whether there are sufficient grounds for further action under the Act

- managing investigations into disclosures, including determining whether to deal with a disclosure under the Act, initiate an investigation or cease an investigation

- coordinating the handling of a disclosure with the senior officer of another federal public sector organization, if a disclosure or an investigation into a disclosure involves that other organization

- notifying, in writing, the person or persons who made a disclosure of the outcome of any review or investigation into the disclosure and of the status of actions taken on the disclosure, as appropriate

- reporting the findings of investigations, as well as any systemic problems that may give rise to wrongdoing, directly to their chief executive with any recommendations for corrective action

Other relevant terms

- allegation of wrongdoing

The communication of a potential instance of wrongdoing as defined in section 8 of the Act. The allegation must be made in good faith, and the person making it must have reasonable grounds to believe that it is true.

- disclosure

The provision of information by a public servant to their immediate supervisor or to a senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing that is made in good faith and includes one or more allegations of possible wrongdoing in the public sector, in accordance with section 12 of the Act.

- disclosure that was acted upon (admissible disclosure)

An allegation received in a disclosure where action, including preliminary analysis, fact-finding and investigation, was taken to determine whether wrongdoing occurred and where that determination was made during the reporting period.

- disclosure that was not acted upon (inadmissible disclosure)

An allegation received in a disclosure for which the designated senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing determined that the definition of wrongdoing under the Act was not met or had to be referred to another process or required no further action.

- general enquiry

An enquiry about procedures established under the Act or about possible wrongdoings, not including actual disclosures.

- investigation

A formal investigation triggered by a disclosure. An investigation may look into one or more allegations that result from a disclosure of possible wrongdoing.