Agent of deterioration: dissociation

- Paisley S. Cato, San Diego Natural History Museum

- R. Robert Waller, Canadian Museum of Nature

Table of Contents

- Definition of Dissociation

- Relation of Dissociation to Other Agents

- Origins of Dissociation

- Effects of Dissociation

- Control of Dissociation

- Summary

- Vignettes

- Vignette 1. Accidental Discards

- Vignette 2. I'm not pulling your leg, sometimes stray objects are relocated!

- Vignette 3. Diverse objects present diverse labelling challenges.

- Vignette 4. Note on Historical Labels

- References

- Glossary

Definition of Dissociation

Dissociation results from the natural tendency for ordered systems to fall apart over time. Maintenance processes and other barriers to change are required to prevent this disintegration. Dissociation results in loss of objects, or object-related data, or the ability to retrieve or associate objects and data. It can manifest as:

- Rare and catastrophic single events resulting in extensive loss of data, objects, or object values;

- Sporadic and severe events occurring every few years or decades resulting in loss of data, objects, or object values; and

- Continual events or processes resulting in loss of data, objects, or object values.

This agent affects the legal, intellectual, and/or cultural aspects of an object as opposed to the other 10 agents of deterioration, which mainly affect the physical state of objects. This could be thought of as the metaphysical agent. Another unique characteristic of this agent is that loss in value to one or a few objects within a collection can reduce the value of the collection as a whole. Consider the effect of mixing objects between sample lots. Most large collections are assembled to support research and to serve as authoritative references. If a researcher, biologist, archaeologist, or historian observes a small but significant number of cross-contaminated sample lots, the collection as a whole is considered compromised. Thus, as a result of only a few cross-contaminated sample lots, a collection may lose much research and reference value.

Relation of Dissociation to Other Agents

Continual physical force events or processes, such as abrasion, can contribute to eroding or detaching object labels. Pollutants and pests can degrade and damage labels, while incorrect levels of relative humidity can affect adhesives used to attach labels to objects. Rare or sporadic physical force events can result in mixing objects such that their connection to identifying information is lost. Similarly, fire and flood may damage or destroy labels or tags.

-

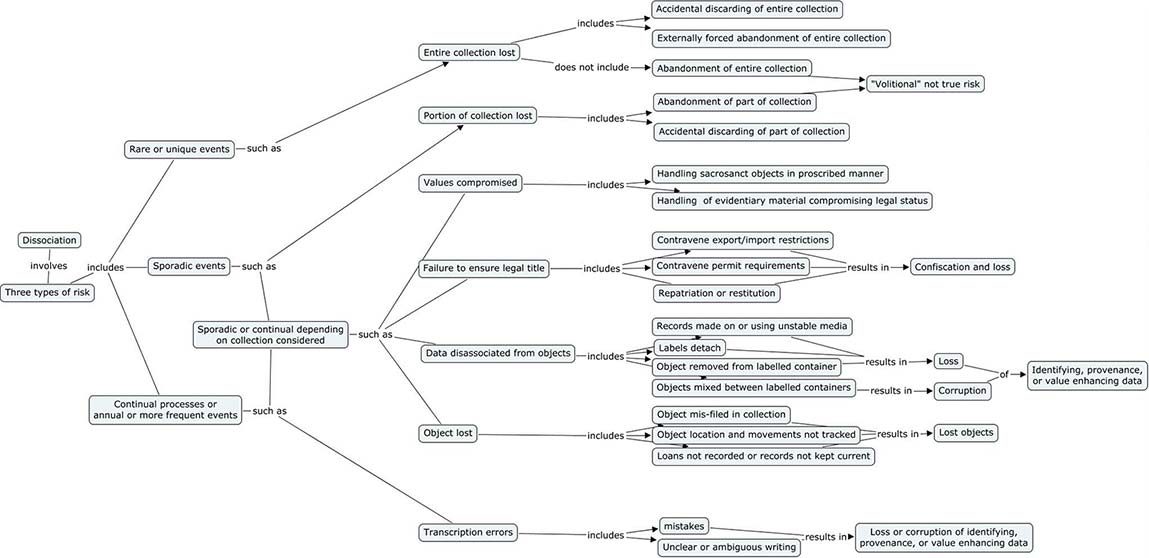

Description of Figure 1.

Dissociation involves three types of risk that includes: rare or unique events; sporadic events; and continual processes or annual or more frequent events.

Rare or unique events could result in the entire collection being lost; either by accident or by an external circumstance that forces the abandonment of the entire collection. “Abandonment” does not include intentional or “volitional” abandonment.

Sporadic events could result in a portion of a collection being lost either by abandonment (not intentional) or accidental discarding. Sporadic or continual events and processes that occur annually or more frequently could result in:

- values being compromised, leading to

- Handling sacrosanct objects in proscribed manner

- Handling of evidentiary material compromising legal status

- failure to ensure legal title, leading to

- Contravention of export/import restrictions and permit requirements

- Repatriation and restitution

- which can result in confiscation and loss

- data being dissociated from objects, such as records made using unstable media, labels that become detached, objects removed from their labelled containers, or objects mixed between labelled containers; transcription errors including: mistakes and unclear or ambiguous writing leading to

- Loss or corruption of identifying, provenance, or value enhancing data

- the object being lost, including:

- mis-filing the object in the collection, not tracking object movements and locations, and not recording or keeping object loans current

- values being compromised, leading to

Sporadic or continual risks due to theft and pilfering also result in displaced objects. Although in these cases objects are lost from instead of lost within a collection, the effects appear similar to misfiling in that objects cannot be located for use or inventory.

Origins of Dissociation

Both actions and failures to act can contribute to dissociation-related risks. An example of an action causing dissociation is misplacing an object. An example of a failure to act is failure to document an outgoing loan.

Actions

Actions include any collection use activities that result in loss of objects, loss of data, or loss of object–data associations.

Examples include:

- Misplacing objects;

- Removing identifying labels or tags from objects;

- Recording object and collection data in an illegible or ambiguous manner;

- Recording object and collection data in nonpermanent manners; and

- Making errors in transcription.

© Canadian Museum of Nature.

© Canadian Museum of Nature.

Other actions resulting in dissociation include handling an object or collection in a manner that is disrespectful of the value to certain stakeholders and, hence, results in loss of value to those stakeholders. Inappropriate contact with culturally sensitive objects is dealt with in Caring for Sacred and Culturally Sensitive Objects. Another example of this type of action leading to dissociation involves objects used as legal evidence. Evidentiary value must be preserved by protecting it from tampering.

Using inappropriate products or procedures can lead to dissociation. Using nonpermanent inks to identify objects or using identification tags that wear to illegibility, crumble to dust due to the use of acidic papers, or become detached can all result in loss due to dissociation.

Failures to Act

Failures to act, such as neglecting to keep collection areas tidy, contribute to high dissociation risks. Failures to act can cause dissociation directly. For example, failure to migrate electronic data to new formats can lead to complete loss of the ability to access data. Failures to act include any situation in which:

- Legal requirements to ensure continued ownership are not adhered to;

- Collection-related data (especially electronic records) are not transcribed or migrated to ensure continued accessibility;

- Object identification is not permanent;

- Objects or collections are not adequately identified to prevent discarding;

- Objects are not tracked closely enough to prevent their becoming lost; and

- activities of maintenance staff are not proscribed enough to prevent accidental discarding or misplacement of objects or parts of objects.

Preventing failures to act requires establishing and maintaining adequate precautionary measures, including registration, tracking, inventory, and handling policies. It also requires an understanding of productivity pressures, including numbers of visitors, loans, and exhibits. Registration systems must be completely committed to so that they are respected in the face of extraordinary productivity pressures.

Effects of Dissociation

The effects of dissociation include compromise or loss of objects, collections, and the data that give them value through context and meaning. The effect can seem slight, such as reducing the certainty that a single object is properly identified. Indeed, no collection is perfectly documented and all collections will have an error rate in identification. However, when an error rate becomes unacceptable to users of the collection, then the entire collection, and not just the objects directly affected, will lose value. This magnification effect, where compromising a few objects and/or their data affects the value of many or all objects, is an insidious aspect of the agent dissociation.

At the other extreme, the effect can be immediate and cause the complete loss of an entire collection and its documentation. This might occur when an organization, not understanding the value of a collection, decides to dispose of it. Collection material might be discarded simply because it is not adequately identified as part of a collection unit. Loss can happen by complete accident; for example, when movers mistake collection materials for other items designated for disposal (Vignette 1).

Complete loss can happen when a shift in purpose or orientation of a collection-holding organization results in management wishing to divest itself of collections through disposal. However, because this risk arises as the result of choice, it would be termed a volitional risk and not be subject to objective evaluation from the perspective of the organization itself. However, from the perspective of society as a whole, collection abandonment, for example, by government departments that change their focus, may represent substantial loss.

General Outline of Effects

The general outcomes of dissociation from any cause are loss of objects, of whole collections, of their associated data, or of their values. "Loss" is used here to mean "becoming unable to retrieve on demand that which is wanted." In the case of data loss, objects or collections lose context and information-related values. In the case of inappropriate use, spiritual, ritual, and other cultural values are lost.

High-sensitivity Objects and Collections

Numerous factors contribute to sensitivity to dissociation risks at both object and collection levels, as well as at both staff and management levels (Table 1).

Factors contributing to dissociation: Characteristics leading to increased risk of dissociation

Object

- Illegally acquired object

- Small object size (difficult to label)

- Fragile objects (difficult to label)

- High cultural value

- Unresolved copyright or ownership issues

- Object currently not "fashionable" (dated taxidermy specimens)

- Object valued for uses not common to bulk of collection (e.g. exhibit value in research collection)

- Object used for destructive sampling or destructive research

Collection

- Large numbers of objects

- High diversity of objects

- Collection data contributed from many diverse sources

- Tradition of illegal object acquisition

- Overall poor condition of collection

- Digital media susceptible to obsolescence

Collection care staff

- Unregulated or unrestricted access to collections

- Staff not aware of legal issues

- Choice of unstable products or poor systems for catalogs and labels

- Incomplete or inadequate record keeping

- Staff not adequately aware of storage organization

- Poor organization of the collection

- Other professionals' sense of collection values and issues not comprehended

- Cultural value not understood or appreciated by custodians

- Untrained volunteers not aware of correct procedures

Management of collection responsibility

- Collection not held in dedicated, appropriate spaces

- Collection care is secondary or tertiary responsibility of staff

- Insufficient, part-time, intermittent staff

- Staff not trained in collection management

- Priority for due diligence much lower than priority for product delivery

- Failure to foster appreciation of collection values

Control of Dissociation

The control of dissociation relies heavily on effective policies and procedures (Vignette 2). In large institutions, establishing and implementing these policies and procedures are often the responsibility of a registrar or collection manager. In smaller museums, they may be implemented by whomever assumes responsibility for the collections, including managers, volunteers, and even students.

Dissociation risks are minimized through meticulous documentation of all transactions, uses, and movements of objects, and through systematic and correct implementation of procedures that link objects to data. This begins with ensuring that legal title to specimens is clear and transferred to the museum. Permits required to collect, obtain, or import objects must accompany the object. Steps involved in accessioning, or formally taking ownership of the object, must be clear and formally documented. Objects must then be securely linked to their accession record and any associated information, other parts, or ancillary collections. This is generally done by assigning a unique identifying number (frequently a catalog number) and registering that number with identifying data in a ledger. Increasingly, computer databases hold the collection registration files. These files must be adequately maintained and updated as well as securely archived and regularly migrated to formats accessible to current computer systems. As well, staff must be trained in maintaining and retrieving this information, including methods for troubleshooting problems.

Equally important are the procedures to physically link the unique identifying number and related data with the object. Standard protocols are essential for:

- The method of labeling;

- The materials used for labels; and

- The sequence of temporary and permanent labels relative to the steps of preparing objects to be added to a collection, placed on exhibit, or sent out on loan.

If reasonable policies and procedures are in place, the critical factor in limiting the risk of dissociation is institutional and individual staff persistence in meeting a high level of documentation standards, despite productivity pressures.

In the case of digital archival collections, it is the entire collection and not only the collection data that is at risk. Especially at risk are digital collections that are not accessed frequently enough to ensure that any required reformatting is completed while the old format can still be accessed. For many institutions, linking the back up and reformatting of digital collection information with that of corporate electronic records management may be the most effective strategy for managing migration and back up.

Stages of Control

Effective policies and procedures are the key to controlling dissociation risks. Furthermore, developing and implementing such efforts must involve periodic updating, training, and assessment to ensure quality control.

Avoid

As always, avoiding a risk is the preferred approach whenever possible. Always ensure that a clear title to objects is obtained before objects are acquisitioned. Label all objects or groups of objects with identifying numbers.

Block

Develop and implement policies and procedures to ensure adequate registration tracking of all object movements and assure standards of labelling are systematically and correctly applied.

Detect

Regularly scheduled inventories improve the probability of detecting symptoms of dissociation. In large collections, inventory of a sample or subunit of the collection is a viable alternative to a full inventory. Proofreading data after entry or migration is essential to detect transcription or migration errors.

Respond

Implement procedures for replacing faded or otherwise deteriorated labels, re-filing of used collection materials, and so on. Periodic training in procedures for volunteers, staff, and collection users also helps mitigate these risks. Data cleanup and reconciliation of inventory discrepancies are other examples of responses when dissociation problems are detected.

Recover

Maintain and use a system for documenting objects dissociated from their data and data dissociated from their objects. This will usually involve a registry of dissociated labels, catalog entries, and/or specimens that can be consulted to seek matches as new dissociated parts are discovered. A practice of asking collection users to bring dissociated objects to the attention of the collection manager will also help recover misfiled objects. For digital collections that have been rendered unusable due to an outdated format, arrangements for reformatting might be made.

Levels for Control

Dissociation is primarily controlled at the policy and procedure level as well as at the object level.

Stringent adherence to procedures for acquiring, registering, and tracking objects is of utmost importance. Temptations to succumb to productivity pressures, such as allowing a loan to be sent or taken away without full documentation, cannot be tolerated. Requirements for documenting and tracking specimens are defined and maintained within the field of museum registration and have been well described by that area of specialization (consult Buck and Gilmore ).

Procedures to research the need for and the acquisition of permits for object loans or acquisition must be systematically applied. Many permit requirements apply to objects in cultural collections, as well as to natural history collections, because legal statutes apply to the movement or use of components or materials of objects (e.g. feathers, ivory), not only to the initial collecting of the animal.

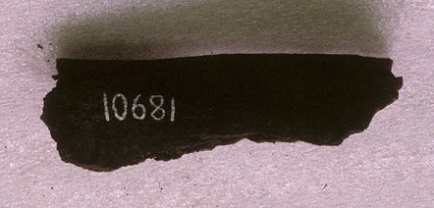

Canadian Museum of Civilization, QdJb-3:69. IMG2012-S90-2660-Dm.

Buck and Gilmore () provide descriptions of general permit requirements. Consult provincial, state, and federal agencies for current requirements (e.g. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora; Cultural Property Import and Export Act (Canada); Canadian Cultural Property Export Control List).

At the object level, objects must be identified to enforce a link between the object and its associated data. That associated data will include acquisition files indicating proof of ownership; catalog files including provenance information and conservation documentation; research files including field notes and referrals in publications; and ancillary material such as molds, casts, photographs, radiographs, preparations for and results of analyses, and so on. In general, simple systems involving a unique number, together with an institution identification code are preferred to more complex systems with encoded information. Simpler systems tend to be more sustainable over long periods of institutional history.

Objects must be labelled (Vignette 3). Ideally, the catalog or registration number is physically associated with the object, usually by marking or labelling. In some cases that is not possible. For extremely small objects and those with very friable surfaces, direct marking of the object may not be practicable. In these cases, the catalogue number is marked on an attached label, on the (most unique) container holding the object(s), or on an integral part of the support for the object or object container system.

Application of numbers directly to objects has been the most common way of ensuring unique identity. The techniques for applying numbers are well established. Several publications deal with the subject in detail (see Canadian Conservation Institute a and b; Ogden ; and the Museum Documentation Association website). In general, "solid" materials, such as stone, metal, and wood, have a separating layer painted onto the object between the number and the surface. Alternative techniques are used on softer and more absorbent materials, such as paper, leather, and textiles. In addition to an object's material, texture, and structure, selection of a labelling method requires considering specimen use (exhibit, research, reference), facilities such as fume extraction, consistency within a collection or institution, and sometimes other issues.

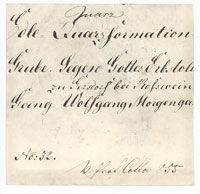

Labels, either attached to objects or kept loose but in association with the object, may have historical or aesthetic value of their own. These labels warrant special consideration (Vignette 4).

Control Strategies

Control strategies for different levels of intervention are available.

Summary

Dissociation results in loss of objects, object-related data, or the ability to retrieve or associate objects and data. The principal means of control against the risk of dissociation is establishing and complying with policies and procedures meant to document and control the acquisition and movements of objects. The ability to exercise professional discipline to abide with these policies and procedures through periods of great productivity pressures is often the risk-limiting factor for dissociation. Where appropriate and adequate policies and procedures are not instituted and respected, dissociation will likely be the greatest risk to a collection.

Vignettes

Vignette 1. Accidental Discards

Beauty is in the eye of the beholder

Without doubt, every collection of any significant size and age will have suffered incidents of accidental discarding of objects. This happens almost annually with contemporary installation art where sanitation workers will discard what appears to them to be something in need of disposal. The installation piece Anna Dropped Her Basket by Leslie Rech was cleared away the day after installation by a city "clean team."

Headline read "Canadian artifacts sent to garbage dump"

Accidental discarding is a real and ever present risk to all collections and no collection is completely immune. Rarely, but on occasion, accidental discarding can take on catastrophic proportions. In , for example, workers mistook an entire Ontario Archaeological Society collection of 433,000 objects stored in 289 boxes as garbage for disposal.

The boxes were being stored in a corridor with an assortment of used equipment, but were segregated in a locked cage. A message advising of the impending clean up had circulated through management, but not been received by the curator responsible for the collection. Risk factors for this collection can be identified in Table 1. Note: check the section dealing with the management of collection responsibility.

Vignette 2. I'm not pulling your leg, sometimes stray objects are relocated!

"Missing Leg Found"

Since , the Canadian Museum of Nature's (CMN) Vertebrate Zoology collections have included a mounted skeleton of a horse imported to Canada by the former Governor-General Prince Albert, Duke of Connaught. For an unknown reason, the horse lost a leg at some point and was thereafter referred to by staff as the "three-legged horse." During a teaching stint at Carleton University early in , CMN paleontologist Natalia Rybczynski noticed that the university's Biology Department had a freestanding horse leg covered with white paint with holes for attaching wires. The vagrant leg proved to be the missing limb of the CMN's horse. It had probably ended up at Carleton some 30 years ago as part of an improperly documented loan. With permission from the Biology Department, the stray leg was reunited with its rightful owner.

© Canadian Museum of Nature

Vignette 3. Diverse objects present diverse labelling challenges.

The wide range of object types, materials, sizes, and uses found in collections leads to a great variety of identification techniques including direct numbering, tagging, labelled containers, etc.

© Canadian Museum of Nature

Figure 9b. Insect and label held together on a pin. Photo by Francois Genier.

© Canadian Museum of Nature

© Canadian Museum of Nature

© Canadian Museum of Nature

© Canadian Museum of Nature

Canadian Museum of Civilization, IMG2012-0264-0001-Dm.

Canadian Museum of Civilization, IMG2012-0264-0002-Dm.

Canadian Museum of Civilization, IMG2012-0264-0003-Dm.

Canadian Museum of Civilization, IMG2012-0264-0004-Dm.

Canadian Museum of Civilization, IMG2012-0264-0005-Dm.

Canadian Museum of Civilization, IMG2012-0264-0006-Dm.

Canadian Museum of Civilization, IMG2012-0264-0007-Dm.

Canadian Museum of Civilization, IMG2012-0264-0008-Dm.

Canadian Museum of Civilization, IMG2012-0264-0009-Dm.

© Canadian Museum of Nature

Vignette 4. Note on Historical Labels

Meticulous primary collectors will label objects soon after acquisition, and although these labels primarily contain information, they may also have aesthetic and historical value. The information on the labels is generally transcribed to the institution's own system, but the individual details of handwriting, etc., remain of historical and sometimes aesthetic interest. Over time the label paper can become very fragile, inks may fade, and adhesives can also weaken. Such labels should be treated with great care. Deteriorating labels may be encased in Mylar and remain directly attached to the object. If labels become detached, a decision is required whether or not they should be re-adhered. This requires analyzing the risks and benefits of re-adherence relative to separate storage. If labels are not to be re-adhered to the object, they should be enclosed in a clearly identified poly(ethylene terephthalate) or Melinex envelope, which is closely referenced to the object. This discussion has focused on attached historical labels. Similar issues arise when considering detached object labels, sometimes called tray labels.

© Canadian Museum of Nature

©Catharine Hawks.

©Catharine Hawks.

References

-

Canadian Conservation Institute. Applying Registration Numbers to Paintings. CCI Notes 1/5. Ottawa: Canadian Conservation Institute, a.

-

Canadian Conservation Institute. Applying Accession Numbers to Textiles. CCI Notes 13/8. Ottawa: Canadian Conservation Institute, b.

-

Ogden, Sherelyn, ed. Caring for American Indian Objects. St. Paul, MN: Minnesota Historical Society Press, , pp. 214–220.

Key Readings

-

Buck, Rebecca A., and Jean Allamn Gilmore. Museum Registration Methods. Washington DC: American Association of Museums, .

-

Malaro, Marie C. A Legal Primer on Managing Museum Collections. Washington DC: Smithsonian Institution Press, .

-

Museum Documentation Association. Labelling and Marking Museum Objects. SPECTRUM Procedure: Acquisition - Step 13.

-

Simmons, J.E. Things Great and Small: Collections Management Policies. Washington DC: American Association of Museums, .

Glossary

- Acquisition

- The appropriately documented transfer of title to the museum of an object or objects acquired by purchase, gift, bequest, field search, exchange or any other method which transfers title to the museum.

- Labelling

- The process of preparing and affixing labels to folders, other file units, and containers; process of preparing labels to accompany objects or specimens.

- Permit

- A document which grants a person the right to do something not forbidden by law but not allowable without such authority.

- Registration

- The process of developing and maintaining an immediate, brief, and permanent means of identifying an object for which the institution has permanently or temporarily assumed responsibility.(definitions taken from Cato, P. S., Golden, J. and McLaren, S. B. ( eds.). . MuseumWise: Workplace Words Defined. Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections, 388 pp.)

Thanks to the Centro Nacional de Conservación y Restauración in Chile, the Canadian Conservation Institute’s web resource Agents of deterioration, translated into Spanish by ICCROM, is now available free of charge. Intended for curators and conservators, the resource identifies 10 primary threats specific to heritage environments.