Agent of Deterioration: Water

David Tremain

Table of Contents

Introduction

This section deals with water in its liquid form, but also includes dampness resulting from condensation and rising moisture. (Visit "Incorrect relative humidity" for information on water vapour.) It identifies the major issues with incidents that cause water damage in collections, and provides strategies to prevent or minimize any occurrence. This section does not describe recovery strategies after damage has taken place.

| Natural | Technological/Mechanical | Accidents |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Water damage is a depressingly regular occurrence in heritage institutions. It can result from natural occurrences, technological hazards, or mechanical failures. However, the majority of water-related problems in cultural institutions are the result of accidents or neglect. Many custodians underestimate the likelihood and effects of sporadic events such as water leaks. There is a tendency to use basements for collection and archival storage and to leave boxes of material on the floor, perhaps only "temporarily." Many containers for paper documents and small artifacts purchased by museums are acid-free, but few institutions consider acquiring watertight boxes made from fluted polypropylene. Some of the factors and events typically leading to water damage are shown in Table 1.

A great many of the materials that museum objects are made of are highly susceptible to contact with water and can be severely damaged by even brief contact, while others may be exposed to water for longer periods without harm. This situation is complicated by the combination and range of materials that may comprise each object. In addition, the vulnerability of individual objects to water can be affected (i.e. increased) significantly by the state of the degradation of the materials. For example, a badly degraded, acidic wood pulp paper will absorb more water, leading to heavier water staining and "tide lines." Approximate types of damage to some common museum materials are shown in Table 2.

| Material | Damage caused by water |

|---|---|

| Bone products | Possible cracking and distortion, staining, degradation of collagen, teeth (skulls) loosen, physical weakness (depending on how initially cleaned) |

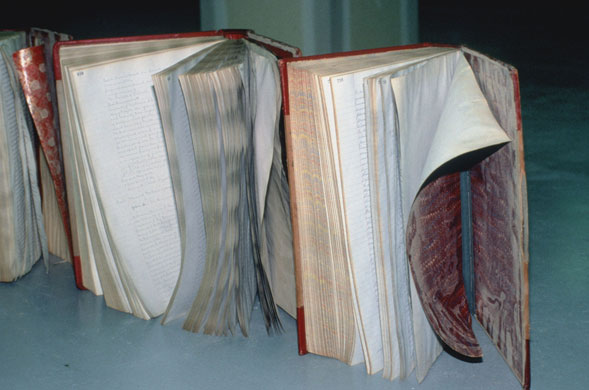

| Books | Softening, distortion, running of inks and dyes, staining; softening, distortion and subsequent hardening (on drying) of leather bindings |

| Ceramics | Porous surfaces stained, salts or patina (if archaeological) lost |

| Glass | Existing glass "disease" stimulated |

| Keratins | Feathers matted, dyes run |

| Leather | Vegetable-tanned objects shrunk, distortion, staining, degradation of collagen and turning into gelatin |

| Metal | Reactive (e.g. ferrous) metals corroded, existing corrosion stimulated |

| Paintings | Delamination, sizes and water-soluble glazes dissolve, varnishes blanch, wooden panels distort, frame or stretcher joints loosen, canvases distorted (cockling) |

| Paper | Softened, inks run, staining, tide lines, distortion (cockling) |

| Photographs | Softening of the paper, gelatin swells, staining, emulsion lifted, dyes run |

| Plant materials | Shrinkage, distortion, staining, solubilization of adhesives |

| Plastics | Porous surfaces stained |

| Shell | Porous surfaces stained, efflorescence |

| Stone | Porous surfaces stained |

| Textiles | Dyes run, staining |

| Wooden objects | Shrinkage, distortion, staining, splitting, delamination, blanching of varnishes, joints loosen, swelling |

| Any organic objects | Mould |

Control Strategies

This section follows the strategies of Avoid, Block, Detect, Response, and Recover/Treat. However, the fifth strategy, Recover/Treat, is not covered in detail because it deals with specific procedures following water-related incidents and is, thus, beyond the scope of this resource.

Avoid

Location of building

Avoidance of water hazards starts with the location of the building. In almost all cases, the building location is fixed and, thus, the only ways to avoid location-related hazards are:

- If it is new construction, do not select a building site close to a body of water, or in a flood plain. Such is the case with Old Fort William in Thunder Bay, Ontario, which experienced major floods in , , , , and (Figure 1 shows the level of the water during the flood). Implementing this strategy would only be possible during the site selection phase of new building planning.

- Raising (new or an existing building) the structure above the projected flood line. This requires extensive engineering and is often very costly.

- Relocating an existing building to a safer area (i.e. on a higher ground foundation). However, relocating buildings is costly and logistically difficult, although it has been done for historic houses on many occasions. Recreated historic sites, such as King's Landing in New Brunswick, is one example.

Design issues

The building envelope must maintain water-tightness in order to avoid external sources of water. So consider the following when a new facility is being designed:

- Do not incorporate standing water into the building design (e.g. ornamental fountains and reflecting pools).

- Avoid designs that incorporate:

- flat roofs, because of their tendency to drain poorly and accumulate snow and ice. However, depending on the size of the building, this is difficult to avoid. Cost is also a factor if deciding on another type of roof; and

- large glass surfaces such as skylights, domes, and large windows facing the prevailing wind that will leak after heavy precipitation.

Where none of these solutions is feasible, it is necessary to avoid all potential sources of water, both external and internal.

Strategies for storage and display areas

- Avoid displaying, storing, or examining objects near sources of water, such as:

- in the basement or attic. If basement storage is unavoidable, raise objects at least 10 cm off the floor; and

- under pipes, air conditioners, or other sources of water. If storage under pipes is unavoidable, try to position shelving in between pipes.

- Ensure pipes are well-insulated against freezing in winter.

- Seal all openings around pipes to prevent water leaks.

- Avoid:

- using carpeting in the stacks or storage areas. If carpeting becomes wet, it may absorb a large amount of water and greatly increase the humidity level;

- placing shelving or objects against walls because water from above may run down the walls;

- placing objects on or against uninsulated exterior walls or near windows because there is the potential for damage from leaks or condensation; and

- locating janitors' sinks in or above collection areas.

Store collections separately so that they will affect each other as little as possible if they become wet (e.g. store coloured textiles separately from whites).

Protocols for construction or renovation

Water problems caused by accidents during construction or renovations can be avoided by supervising contractors, and by ensuring that they adhere to explicit guidelines. A construction accident at the Chicago Historical Society in where a water main was severed resulted in considerable damage to collections, and almost caused loss of life. Points to consider in forming such guidelines are:

- providing orientation for contractors to ensure that they understand the sensitivity of the material they will be working around;

- controlling sources of water (e.g. sites for mixing cements and plasters);

- installing protective shells during construction/renovations;

- identifying water control valve(s) (domestic and sprinkler systems);

- taking special care when:

- inspecting or servicing sprinkler systems; and

- working or carrying out renovations close to sprinkler heads;

- relocating or covering objects near work being carried out on plumbing; and

- having incident response procedures in place (e.g. who will do what if a pipe leaks or bursts, a sprinkler head is damaged, etc.).

Building maintenance strategies

Many water problems, particularly in smaller museums or historic houses, are caused by poor maintenance, or the lack of it. A routine maintenance program should be carried out to either prevent or mitigate the effects of water, such as:

- developing a checklist to ensure that the building's perimeter is visually inspected (external/internal). Some potential building deficiencies or problems are:

- roof leaks;

- chimney leaks;

- faulty or loose roof shingles and flashings;

- leaking windows and doors;

- missing chinking in log walls;

- blocked eavestroughs;

- poor drainage or grading;

- cracked foundations or parging;

- footings that are too small;

- vegetation too close to the building (i.e. trees, vines, shrubs); and

- splits or cracks in structural columns and supports;

- ensuring a staff member (or contractor) is specifically assigned to carry out routine maintenance of the building and correct deficiencies;

- installing eavestroughs and downspouts to drain water away from the building, and having a scheduled program in place to inspect and clean eavestroughs and downspouts to prevent blockage from leaves or debris;

- using landscaping to ensure there is a sloping away from building foundations to drain away water;

- not allowing ice build-up on roofs in the winter. Installing heating wires in vulnerable areas to reduce ice and snow; periodically inspecting to ensure the system is operational; using professional roofers for ice and snow removal;

- ensuring the roof is in good condition (e.g. no loose tiles or shingles, no holes, etc.) and taking corrective actions in a timely manner;

- installing a sump pump and including a battery back-up system in the event of a power failure if flooding is a recurrent problem; and

- carrying out daily inspections at the end of the day before closing to ensure there is no running water left unattended, or toilets overflowing.

Strategies for storage and display

- Use water-resistant storage containers.

- Ensure that drawer units are watertight and that small objects in storage are enclosed in plastic bags or boxes.

- Use display case covers wherever possible; they will at least prevent dripping or spraying water from falling on objects.

Block (Mitigate)

Where a direct threat cannot be avoided, having a preventive program in place that anticipates the problem and includes procedures or measures for mitigating its effects can be effective. These include:

- being aware of meteorological conditions (e.g. weather warnings, flood warnings, etc.) in the institution's locale by monitoring the weather networks, news media, the Internet, etc.;

- if the building is in an area prone to flooding or high precipitation, ascertaining the highest level for floodwater (such information is often kept on file by municipal authorities);

- keeping informed of decisions by water conservancy authorities to raise/lower water levels;

- having sandbags ready to place around doors and below-grade windows when bad weather is predicted;

- being prepared to tape or board up windows and doors;

- being prepared to move collections to higher levels within the building or to a temporary safe location(s);

- assembling equipment such as pumps, wet-dry vacuums, mops and squeegees ("response cart" or a designated storage area) for dealing with such emergencies, or at least know where the equipment can be acquired in a hurry.

- placing staff on full alert; and

- placing tarpaulins or industrial polyethylene sheeting over any parts of the building where water might seep in during a rainstorm.

| Basic supplies | Substantial supplies | Full contingency supplies |

|---|---|---|

|

Basic suppliers +

|

Substantial supplies +

|

Detect

The first priority of detection is to conduct a risk assessment to identify the existing level of risk. This should be coordinated with an inspection of the building's exterior and interior and its collections for signs of water. Regular inspections should follow. These can be integrated into routine housekeeping and monitoring tasks..

Detection can be in three stages:

- The visible presence of liquid water from a flood or leak, which warrants immediate action (see "Response").

- Signs of insidious water damage on both the building and the objects that indicate a water problem that should be identified and traced back to source, such as:

- efflorescence on stone, concrete, or brickwork on the building exterior;

- plant growth on the building exterior, particularly mosses and algae;

- efflorescence on stone, concrete, brickwork, and plaster on the building interior;

- algal and fungal growth on interior walls;

- peeling paint (this can also be caused by poor quality paint, poor application, or high fluctuation of relative humidity);

- excessively cool walls or floors;

- drips and stains on walls, floors, and ceilings;

- "tide lines" on floors;

- external corrosion on pipe work and metals fittings attached to walls;

- movement of floorboards

- visual signs of mould growth or rot; odour (i.e. a damp smell); and

- widespread damage, such as that referred to in Table 2, is an indication of water problems in the collection or storage area.

- Indications from alarm systems or other monitoring devices of the presence of water.

Monitoring systems

Install:

- water detectors in all areas where it is suspected water could enter the building or leak from interior fittings;

- a monitored environmental system to indicate changes (fluctuations) in relative humidity;

- dataloggers; and

- recording hygrothermographs.

Response

Response procedures are initiated when an incident is detected. In general, these strategies can be devised from the results of "worst case" scenarios. Following are measures that can be taken:

Procedures for immediate response

In any response to an emergency, whether it be water or another problem, human life and safety always come first. Major floods can bring with them hazards such as:

- contaminated water (bacteria, fecal matter)

- animal or human remains (worst-case scenario, i.e. Hurricane Katrina and New Orleans flood)

- disease

- mould

- debris (brick, concrete, wood, nails, etc.)

- slippery floors (e.g. from mud, ice)

- live electrical wires or electrical devices in water

- extremes of temperature

Health and safety precautions

It should be assumed that water is contaminated until proven otherwise. Water may need to be sampled and tested for possible contamination, particularly if it is a widespread flood, such as the Peterborough flood in , where water was found to be at a level 4 contamination with E-coli present. Therefore, ensure that hepatitis A and tetanus shots are up-to-date and always wear appropriate CSA- or ASA-approved personal protective equipment (PPE):

- Tyvek™ overalls

- N95 or N100 respirator

- plastic gloves

- rubber boots or bootees

- hard hat

Procedures for controlling water

- Contain the flow of water.

- Shut the water off at the source, where possible (may involve a facilities manager or city official).

- Protect (i.e. cover, remove) any collections immediately under the source of, or in the path of, water.

- Remove standing water with wet/dry vacuums, pumps, mops, and squeegees.

- Remove any materials capable of retaining water (i.e. carpeting, drywall, upholstery).

- Maintain air circulation (fans, dehumidifiers, open windows).

- Monitor the environment and try to return it slowly to its original temperature and relative humidity.

Recover/Treat

Recover or Treat deals with implementing measures to prevent further damage to the affected collections, as indicated in Table 2, and, possibly, carry out conservation treatments (not discussed here). The major goal is to prevent the following:

- mould attack and subsequent damage;

- further physical damage due to drying out too quickly or too slowly, which can cause tearing, distortion, splitting, cracking, etc.;

- surfaces or objects sticking to each other;

- absorbent materials (such as paper, textiles, leather) hardening due to soaking and subsequent drying;

- accretions on surfaces from contaminants in water;

- dissolution of pigments, dyes, water-soluble adhesives, etc.;

- loss of information;

- loss of fragments from paper, paintings, ceramics, etc.; and

- loss of objects.

The efficiency and effectiveness of recovery from water damage depends on the facility's emergency and disaster preparedness. It is essential that the organization formulates and keeps current a specific plan. This will include at least the following:

- priority of the treatment specific to the collection;

- location information on all objects;

- contact tree for personnel;

- contacts for local emergency services;

- contacts for conservation advice and assistance; and

- location of supplies, equipment and facilities.

Vignettes

Vignette 1. Perth-Andover Flood, New Brunswick

During the winter of –, there had been consistently heavy snowstorms in the area of Perth-Andover, New Brunswick. On , the ice on the river began to break up, causing an ice jam to form. On the evening of the first day of the flood, the river level began to rise to the flood level mark of 78 m, and early the next morning (), it had risen well above it. In the early hours of the morning, the New Brunswick Emergency Measures Organization issued a flood warning. The Royal Canadian Mounted Police and the local police force began warning residents in low-lying areas. The river had crept across the main street where the archives building is located, beside the St. John River and in a known flood zone. A State of Local Emergency was declared and the mayor ordered that all electrical power be turned off. The local hospital was evacuated and town residents were urged to leave their homes as soon as possible. Between and , the population of the entire downtown district was evacuated.

Approximately 2 m of water reached the first floor level of buildings, including the archives building. Some of the records were stored in a vault, while others were on open shelves or in filing cabinets. Staff were able to recover all items stored in it. They relocated the microfilm and microfiche collections to a nearby motel before the water rose.

The water level peaked at 79.5 m in mid-morning on the second day (), and the ice jam broke. The water receded below flood level and some residents were allowed to return to their homes.

When conservators from Ottawa and Fredericton were finally allowed to enter the archives building on the Saturday following the flood, they found various types of ledgers, court records, and land grants on linen, some of which were wet, while others were floating in the water. These were retrieved and taken, along with thousands of other documents and bound material, to a provincial government warehouse outside Fredericton.

Drying this material presented a number of problems because there was neither access to freezing or vacuum freeze-drying facilities, nor other staff to assist the conservators. It was, therefore, decided to air-dry everything, using whatever absorbent materials were available (blotting paper, paper towels, rolls of Kraft paper, etc.), while circulating the air with four freestanding fans. Because there were no tables available, the documents were laid out on blotting paper on the floor until they were dry, whereupon another batch replaced them. The air-drying caused cockling and wrinkling of paper and detachment of some bindings.

Inevitably there are things to be learned from disasters, but it is necessary to resist the temptation to criticize, and to concentrate instead on learning and developing. Following are some pointers:

- Formulate a disaster plan for the facility, and ensure that it is kept up to date. This would include a system for establishing priorities in evacuating collections from the building.

- Keep a kit of essential materials, such as blotters, paper supplies, and plastic sheeting, in stock.

- Ensure access to equipment and facilities. It is not necessary to have sophisticated equipment on hand, but a network of contacts should be developed and maintained.

- Provide more effective waterproofing for objects.

Vignette 2. Cumberland Heritage Village Museum Flood, Ontario

The Cumberland Heritage Village Museum's storage facility is an old fire hall owned by the City of Ottawa. Objects stored in it consist mainly of domestic furniture, agricultural implements, an upright piano, a pump organ, and archival records relating to the history of the museum. City staff inspected the facility once a month during winter 2003. During one of the regular inspections, it was discovered that over 2,000 m3 of water had leaked from a broken 3/4 in. water pipe in the roof after both furnaces had broken down. The cause appears to have been a malfunction of the roof-mounted furnace — a failure of the oil supply resulted in the furnace shutting down, thus freezing the building and causing a pipe to burst. During this flood, the outside temperature dropped to –25°C, causing the flowing water to freeze. The water had cascaded onto the objects below. It was fortunate that the building had a central drain, otherwise the water might have risen a metre or more before freezing solid. It is unknown exactly when the leak occurred, but it was thought to have been within a two-week period preceding the inspection because no one had been there in the meantime. Had it not been for the inspection, the leak would not have been discovered until much later. Due to the location of the leak, only about 15 to 20% of the storage room area was affected.

While all smaller objects had been placed on shelves and covered with polyethylene sheeting secured with Velcro, in some places the force and quantity of water had displaced the polyethylene and soaked the objects. Smaller objects, that were stored on metal racks covered with polyethylene, still in position fared well. This combination of good planning and industry saved the greater majority of this material from further harm. The larger furniture and agricultural implements were soaking wet. The upholstery of some of the furniture was also saturated, and some furniture was encased in ice and had icicles hanging from it. Wood had warped and split, layers of paint had peeled and flaked off, and some veneers had started to lift. Other objects affected by the water included the paper sleeves for 78 rpm records, archival documents in coloured file folders or plastic ring binders, and some receipt books.

The greatest danger to the collection was from attack by mould. In order to speed drying of the room, and to minimize mould growing during the drying, the large vehicle-sized doors at each end of the building were raised slightly and the furnaces problems were rectified, and the furnaces were turned on. Air circulation was ensured by placing large commercial fans in the gap below the doors at one end. As soon as the furnaces were running, the polyethylene sheet was removed from the racks to ensure the greatest airflow over and around all the wooden items. In less than a week, the relative humidity was reduced to 40%. The fans were kept running until it was determined that all the objects were dried out.

Paper documents were transferred to clean, dry boxes and placed in an unheated storage building, so they froze quickly with the outside temperature being approximately –25°C. This was a stopgap measure until they could be placed in a commercial freezer facility and vacuum freeze-dried.

In view of the severity and duration of the flood, damage to the collection was not major. This can be attributed to how fast the situation was assessed, and drying and stabilization were carried out. Some painted furniture suffered losses to the finishes due to the wood swelling. Veneered wooden objects absorbed so much water that the veneer buckled and detached from the underlying frame. Pieces of furniture that stood with their feet in water had tide line stains in their finishes directly above the feet. The paper sleeves on 78 rpm records were mostly discarded.

In order to avoid a similar disaster in the future, or to be prepared for similar events, the following points should be considered:

- Formulate a disaster plan for the facility, and ensure that it is kept up to date.

- Keep a kit of essential materials, such as blotters, paper supplies, and plastic sheets, in stock.

- Ensure access to equipment and facilities. It is not necessary to have sophisticated equipment on hand, but a network of contacts should be developed and maintained.

- Install alarms or data loggers with remote read-outs, to warn of the presence of water or fluctuating temperature and relative humidity.

- Increase the frequency of cursory inspections.

- Institute regular maintenance schedules for all installations and machinery

- Provide more durable waterproofing for open shelves with large objects.

References (Key Readings)

-

Ball, Cynthia, and Audrey Yardley-Jones, eds. Help! A Survivor's Guide to Emergency Preparedness. Museum Excellence Series: Book 3. Edmonton: Museums Alberta, .

-

Buchanan, Sally. Emergency Salvage of Wet Books and Records. North East Document Conservation Center Technical Leaflet, Emergency Management, Section 3, Leaflet 7. North Andover: NEDCC, .

-

Government of Canada. Flood Damage Reduction Program, on .

-

Government of Canada. Keeping Canadians Safe, on .

-

Hutchins, Jane K., and Barbara O. Roberts, eds. First Aid for Art. Essential Salvage Techniques. Lenox, MA: Hard Press Editions, .

-

Wellheiser, Johanna, and Jude Scott, eds. An Ounce of Prevention: Integrated Disaster Planning for Archives, Libraries and Record Centres. 2nd edition. Maryland and London: Scarecrow Press, .

Thanks to the Centro Nacional de Conservación y Restauración in Chile, the Canadian Conservation Institute’s web resource Agents of deterioration, translated into Spanish by ICCROM, is now available free of charge. Intended for curators and conservators, the resource identifies 10 primary threats specific to heritage environments.