Archived: Policy update on restricting food advertising primarily directed at children: Overview

Health Canada sought your feedback on this policy update between April 25 and June 19, 2023. For more information, please visit Consultation: Restricting food advertising primarily directed at children.

On this page

Purpose of policy update

Health Canada intends to amend the Food and Drug Regulations to restrict advertising to children of foods that contribute to excess intakes of sodium, sugars and saturated fat, as noted in our Forward Regulatory Plan. This is a part of our Healthy Eating Strategy and commitment to protecting children's health.

Between 2016 and 2019, we consulted extensively on a policy proposal to restrict food advertising in different settings and media. We are now proposing a targeted approach to introducing restrictions, focusing on television and digital media first.

These restrictions aim to reduce children's risk of developing overweight, obesity and diet-related chronic diseases, now and later in life. They support this objective by limiting children's exposure to influential food advertising in media where children spend much of their time and are highly exposed to food advertising. Along with other Healthy Eating Strategy initiatives, this would support healthy food environments, which in turn contribute to healthy eating behaviours.

Restricting food advertising to children has been a Minister of Health mandate commitment since 2015. The Minister of Health's December 2021 Mandate Letter included a commitment to advance the Healthy Eating Strategy, including supporting restrictions on food advertising to children.

Learn more about:

- Minister of Health Mandate Letter

- Health Canada's healthy eating strategy

- Monitoring food and beverage advertising to children

- Forward Regulatory Plan 2022-2024: Amendments to the Food and Drug Regulations (Restricting the Advertising to Children of Prescribed Foods containing Sodium, Sugars and Saturated Fat)

Definitions

- Advertising vs. Marketing: The Food and Drugs Act (FDA) broadly defines the term "advertisement" but not "marketing". For this reason, Health Canada uses the term "advertising" in this policy proposal. An advertisement includes any representation by any means whatever for the purpose of promoting directly or indirectly the sale or disposal of any food, drug, cosmetic or device (publicité ou annonce), as per section 2 of the FDA.

- Food: The term "food" includes both foods and drinks. As per section 2 of the FDA, 'food' includes any article manufactured, sold or represented for use as food or drink for human beings, chewing gum, and any ingredient that may be mixed with food for any purpose whatever; (aliment)

Introduction

Health Canada is committed to protecting the health of all Canadians. Nutrition plays a critical role in promoting health, and it is important that children develop healthy eating habits early in life. This supports their growth and development and reduces their risk of developing overweight, obesity and diet-related chronic diseases now and later in life, such as:

- diabetes

- osteoporosis

- dental diseases

- some types of cancer

- cardiovascular diseases

Healthy Eating Strategy

Many factors in our food environment influence our ability to make healthy food choices and to follow a healthy pattern of eating. Food costs and the foods available at home, school, and in stores and restaurants, as well as social influences and food advertising, have a major impact on food choices and make healthy eating a challenge for many. Nutritious food choices are not typically what is the most available, affordable, convenient, and widely promoted.

Launched in 2016, Health Canada's Healthy Eating Strategy aims to help Canadians make healthier choices by improving the nutritional quality of foods and healthy eating information, along with protecting vulnerable populations.

As part of the Strategy, Health Canada has already:

- released a new Canada's food guide

- improved the nutrition facts tables and ingredient lists

- published new sodium reduction targets for processed foods

- introduced a ban on partially hydrogenated oils, the main source of industrially produced trans fats in Canadian food

- introduced new front of package labelling requirements for prepackaged foods high in sodium, sugars or saturated fat

Building on these achievements, Health Canada is committed to supporting restrictions on advertising to children of foods that contribute to excess intakes of sodium, sugars and saturated fat. Health Canada is doing this to protect this vulnerable population and help support them in following the healthy eating recommendations in Canada's food guide, which are important to help protect and promote good health and prevent chronic disease.

Children's diets and health

Many Canadians struggle to eat in a healthy way and children are no exception. Health Canada's analysis of children's reported food intakes found that about 10% of vegetables and fruits, about 30% of protein foods, more than 40% of whole grain foods and more than 50% of other foods consumed by children are not in line with recommendations in Canada's food guideFootnote 1. National survey data show that Canadian children have diets high in sodium, sugars, and saturated fatFootnote 2Footnote 3Footnote 4. Health Canada's latest scientific evidence review found convincing relationships between increased intakes of these nutrients of public health concern and the following health conditionsFootnote 5:

- high blood pressure (sodium)

- overweight, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and dental decay (sugars)

- overweight, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease (saturated fat)

While the majority of children have normal blood pressure, children living with obesity have significantly higher blood pressure than other childrenFootnote 6. Blood pressure tends to increase with age, and overweight and obesity are important risk factors for hypertensionFootnote 7.

Nearly 1 in 3 children in Canada lives with overweight or obesityFootnote 8Footnote 9Footnote 10. Children living with obesity have a higher risk of developing:

- fractures

- hypertension

- breathing difficulties

- early markers of cardiovascular disease and insulin resistance

Children living with overweight and obesity also face stigma and discrimination. Children with overweight and obesity are more likely to remain overweight or obese when they become adults, and therefore are more at risk of developingFootnote 11:

- diabetes

- cardiovascular disease

- musculoskeletal disorders

- some cancers, including:

- liver

- colon

- breast

- kidney

- ovarian

- prostate

- gallbladder

- endometrial (lining of the uterus)

Dental decay is common among children. Though national data are not available, we know that children living in rural and remote communities are at higher risk of severe dental decay requiring dental surgeryFootnote 12.

Food advertising and children's food choices

For more than a decade, there has been growing recognition of the negative impact that food advertising has on children's health. Food advertising is designed to increase consumption. Evidence shows that advertising influences children's food attitudes, preferences, and purchase requests, and drives food consumptionFootnote 13Footnote 14Footnote 15.

Canadian and international studies consistently find that the majority of foods advertised to children are those that contribute to unhealthy dietsFootnote 16Footnote 17. Food categories frequently advertised to Canadian children includeFootnote 18Footnote 19Footnote 20Footnote 21:

- candy

- desserts

- chocolate

- snack foods

- baked goods

- restaurant foods

- sweetened dairy products

- sugar-sweetened beverages

- sweetened breakfast cereals

When eaten regularly, these types of foods contribute to excess intakes of sodium, sugars, and saturated fatFootnote 22.

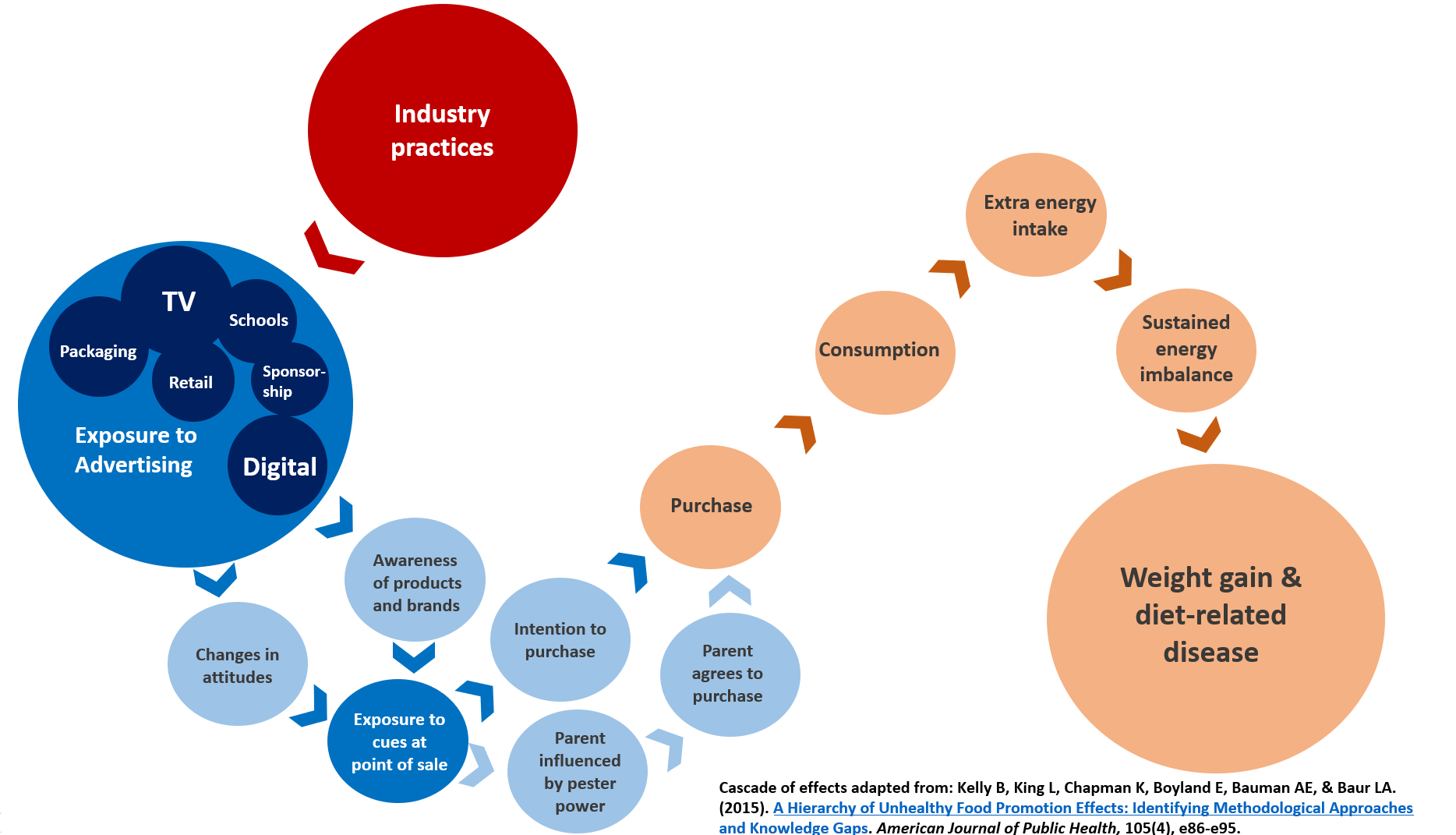

Children are particularly vulnerable to the influence of advertising. Children under the age of 5 are unable to consistently distinguish between advertising and programmingFootnote 23. Most children do not understand the selling purpose of advertising until they reach the age of 8 years old. By the age of 12, they understand that ads are designed to sell products, but most are not yet aware of the persuasive intent of the advertisementFootnote 24. The more children are exposed to food advertising, the more likely they are to request or consume advertised foods. Figure 1 below shows the cascade of effects flowing from ubiquitous food advertising to children.

Figure 1 - Text description

There are a series of circles connected from left to right. Each circle represents a step in the cascade of effects of food advertising to children. Beginning on the top left, industry marketing and advertising practices lead to children's exposure to food advertising in a variety of settings and media, such as on food packaging, on television and in digital media, in retail food stores, in schools and via sponsorship.

Over time this exposure leads to both a change in children's attitudes, and increased awareness of the advertised food products and brands. In addition, children's exposure to food advertising at points of sale leads to both an intention to purchase and parents being influenced by children's pester power. This all leads to increased purchase and consumption of the advertised food, which results in excess energy intake and energy imbalance over the long term. Eventually this contributes to children's weight gain and increased risk of diet-related disease.

This figure has been adapted from a journal article titled "A hierarchy of unhealthy food promotion effects: Identifying methodological approaches and knowledge gaps".

Citation for the journal article:

Kelly B, King L, Chapman K, Boyland E, Bauman AE & Baur LA. (2015). A Hierarchy of Unhealthy Food Promotion Effects: Identifying Methodological Approaches and Knowledge Gaps. American Journal of Public Health, 105(4), e86-e95.

Exposure to food advertising

Children see and hear food advertising throughout their day, across a range of media platforms (such as television, social media and gaming) and settings (such as retail food stores, theaters, and recreation centers)Footnote 25.

The pervasiveness of advertising to children has increased with the growth of digital media and growing use of mobile devices. In the past, television was the main source of advertising to children, but today it is one of many. The popularity of smart phones, tablets and computers has made it easier for advertisers to reach children through multiple channels: from online games that advertise products, to ads that appear on videos and social media. Exposure to food advertising on digital media amplifies the persuasive messaging seen via more traditional forms of advertising, achieving greater ad attention and recall.

Children's screen time increased during the COVID-19 pandemicFootnote 26. Increased screen time increases exposure to food advertising. A 2022 nationally representative survey of children's reported media habits found that Canadian children spend significant amounts of time each week watching television, video on demand and YouTube, using social media, and gaming (24 hours for children aged 2-6, and 30 hours for children aged 7-11)Footnote 27. A growing number of children have access to digital devices, for example 26% of Canadian children between the ages of 7-11 own their own cellphoneFootnote 28.

In 2019, advertisers spent an estimated $628.6 million dollars on food advertising in Canada, 79.5% of this went to ads on television (67.7%) and digital media (11.8%)Footnote 29. When children are watching television or online videos, using social media, visiting websites, and playing games they are in an environment that promotes an unhealthy diet: millions of food advertisements appear in these media every year.

Estimates based on Canadian and international research paint a picture of high exposure to food advertisements on television and digital media. For example, a Canadian study illustrates the immense scale of online food advertising. The study of food advertising on the most popular Canadian children's websites found that there were over 54 million food display ads (for example, pop-up ads and banner ads) in a 1-year periodFootnote 30.

At the individual level, on average, it is estimated that children see 5 food ads per day on television, and 4 per day on social media, in addition to exposure in other media and settingsFootnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33. This exposure typically increases as children grow into teens and have more screen time, especially online. For example, while teens' estimated exposure to food advertisements on television is only slightly higher than that of children, their exposure on social media increases significantly to about 27 ads per dayFootnote 34Footnote 35. When asked, older children and teens report that their exposure to food advertisements is highest on television and digital mediaFootnote 36. Advancements in technology and the ubiquity of user data also allows for increasingly precise targeting of online ads to specific audiences, including childrenFootnote 37.

International research suggests that children from socio-economically disadvantaged and ethnic minority (for example, Black, Hispanic) backgrounds are disproportionately exposed to food advertising on televisionFootnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41. This is due to both targeted advertising and increased screen time. While there is little Canadian researchFootnote 42 that explores children's exposure to food advertising in terms of sociodemographic differences, 2 recent studies suggest that children in racialized and marginalized communities in Canada could be similarly targeted by advertising. These studies are currently unpublished. More data on children's exposure to food advertising is being collected as part of Health Canada's comprehensive surveillance monitoring.

Though exposure to food advertising on television and digital media is the focus of this policy proposal, Health Canada acknowledges that Canadian children are also exposed to food advertising in other types of media and settings, as well as via techniques such as brand advertising, food packaging and labelling and sports sponsorshipsFootnote 43. Health Canada will continue to monitor food advertising in these areas to inform any future restrictions.

Influence of parents and caregivers

Parents' and caregivers' efforts to promote healthy eating at home are undermined by the high volume and influence of food advertisements that children see and hear where they learn, live and play. The majority of these ads are for foods that contain excess sodium, sugars and/or saturated fatFootnote 44.

Restrictions on advertising of certain foods to children are part of a comprehensive suite of initiatives under the Healthy Eating Strategy that are intended to support parents and caregivers in their efforts to select and provide children with healthy meals and snacks.

Footnote

- Footnote 1

-

Based on internal analysis of usual food intake data from the 2015 Canadian Community Health Survey-Nutrition with a comparison to the recommendations in the 2019 Canada's food guide.

- Footnote 2

-

Health Canada. (2018). Sodium Intake of Canadians in 2017.

- Footnote 3

-

Rana H, Mallet MC, Gonzalez A, Verreault MF, & St-Pierre S. (2021). Free sugars consumption in Canada. Nutrients, 13(5), 1471.

- Footnote 4

-

Ng A, Ahmed M, & L'Abbe M. (2021). Nutrient intakes of Canadian children and adolescents: Results from the Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS) 2015 – Nutrition public use microdata files. (Preprint).

- Footnote 5

-

Health Canada. (2019). Food, Nutrients and Health: Interim Evidence Update 2018.

- Footnote 6

-

Statistics Canada. (2021). Health Fact Sheets – Blood pressure of children and adolescents, 2016-2019.

- Footnote 7

-

Statistics Canada. (2021). Blood pressure of adults, 2016-2019.

- Footnote 8

-

Statistics Canada. (2017). Measured children and youth body mass index (BMI) (World Health Organization classification), by age group and sex, Canada and provinces, Canadian Community Health Survey – Nutrition. Table 13-10-0795-01.

- Footnote 9

-

Statistics Canada. (2020). Overweight and obesity based on measured body mass index, by age group and sex. Table 13-10-0373-01.

- Footnote 10

-

Kolahdooz F, Sadeghirad B, Corriveau A, & Sharma S. (2017). Prevalence of overweight and obesity among indigenous populations in Canada: A systematic review and meta-analysis, Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 57(7), 1316-1327.

- Footnote 11

-

World Health Organization. (2021). Obesity and overweight.

- Footnote 12

-

Pierce A, Singh S, Lee J, Grant C, Cruz de Jesus V, & Schroth RJ. (2019). The Burden of Early Childhood Caries in Canadian Children and Associated Risk Factors. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 328.

- Footnote 13

-

Boyland EJ, Nolan S, Kelly B, Tudur-Smith C, Jones A, Halford JCG, & Robinson E. (2016). Advertising as a cue to consume: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of acute exposure to unhealthy food and non-alcoholic beverage advertising on intake in children and adults. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 103(2), 519-533.

- Footnote 14

-

Russell SJ, Croker H, & Viner RM. (2019). The effect of screen advertising on children's dietary intake: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews, 20(4), 554– 568.

- Footnote 15

-

Sadeghirad B, Duhaney T, Motaghipisheh S, Campbell NRC, & Johnston BC. (2016). Influence of unhealthy food and beverage marketing on children's dietary intake and preference: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. Obesity Reviews, 17(10), 945– 959.

- Footnote 16

-

World Health Organization. (2022). Food marketing exposure and power and their associations with food-related attitudes, beliefs and behaviours: a narrative review.

- Footnote 17

-

Pauzé E, & Potvin Kent M. (2021). Children's measured exposure to food and beverage advertising on television in Toronto (Canada), May 2011–May 2019. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 112, 1008–1019.

- Footnote 18

-

Potvin Kent M, Pauzé E, Roy EA, de Billy N, & Czoli C. (2019). Children and adolescents' exposure to food and beverage marketing in social media apps. Pediatric Obesity, 14(6), e12508.

- Footnote 19

-

Kent MP, & Pauzé E. (2018). The effectiveness of self-regulation in limiting the advertising of unhealthy foods and beverages on children's preferred websites in Canada. Public Health Nutrition, 21(9), 1608-1617.

- Footnote 20

-

Vergeer L, Vanderlee L, Potvin Kent M, Mulligan C, & L'Abbé MR. (2019). The effectiveness of voluntary policies and commitments in restricting unhealthy food marketing to Canadian children on food company websites. Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism, 44(1), 74-82.

- Footnote 21

-

Potvin Kent M, Martin CL, & Kent EA. (2014). Changes in the volume, power and nutritional quality of foods marketed to children on television in Canada. Obesity, 22(9), 2053-2060.

- Footnote 22

-

Mulligan C, Christoforou AK, Vergeer L, Bernstein JT, & L'Abbé MR. (2020). Evaluating the Canadian packaged food supply using Health Canada's proposed nutrient criteria for restricting food and beverage marketing to children. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(4), 1250.

- Footnote 23

-

Kunkel D, Wilcox BL, Cantor J, Palmer E, Linn S, & Dowrick P. (2004). Report of the APA task force on advertising and children.

- Footnote 24

-

Carter OBJ, Patterson LJ, Donovan RJ, Ewing MT, & Roberts CM. (2011). Children's understanding of the selling versus persuasive intent of junk food advertising: Implications for regulation. Social Science & Medicine, 72(6), 962-968.

- Footnote 25

-

Potvin Kent M, Hatoum F, Wu D, Remedios L, & Bagnato M. (2022). Benchmarking unhealthy food marketing to children and adolescents in Canada: a scoping review. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice, 42(8), 307–318.

- Footnote 26

-

Madigan S, Eirich R, Pador P, McArthur BA, & Neville RD. (2022). Assessment of Changes in Child and Adolescent Screen Time During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 176(12), 1188-1198.

- Footnote 27

-

Media Technology Monitor Junior. (2022). Data extract from MTM Junior 2022 survey.

- Footnote 28

-

Media Technology Monitor Junior (2022). Called out or dialed in? Kids and cell phones. Analysis of Canadians aged 2 to 17. Report available with Media Technology Monitor subscription.

- Footnote 29

-

Potvin Kent M, Pauzé E, Bagnato M, Guimarães JS, Pinto A, Remedios L, Pritchard M, L'Abbé MR, Mulligan C, Vergeer L, & Weippert M. (2022). Food and beverage advertising expenditures in Canada in 2016 and 2019 across media. BMC Public Health, 22(1), 1458.

- Footnote 30

-

Potvin Kent M, & Pauzé E. (2018). The effectiveness of self-regulation in limiting the advertising of unhealthy foods and beverages on children's preferred websites in Canada. Public Health Nutrition, 21(9), 1608-1617.

- Footnote 31

-

Potvin Kent M, Pauzé E, Roy E-A, de Billy N, & Czoli C. (2019). Children and adolescents' exposure to food and beverage marketing in social media apps. Pediatric Obesity, 14(6), e12508.

- Footnote 32

-

Pauzé E, & Potvin Kent M. (2021). Children's measured exposure to food and beverage advertising on television in Toronto (Canada), May 2011–May 2019. Canadian Journal of Public Health 112, 1008–1019.

- Footnote 33

-

Potvin Kent M, Pauzé E, Roy EA, & de Billy N. (2018). Children's exposure to unhealthy food and beverage advertisements on smartphones and tablets in social media and gaming applications. Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada.

- Footnote 34

-

Czoli CD, Pauzé E, & Potvin Kent M. (2020). Exposure to Food and Beverage Advertising on Television among Canadian Adolescents, 2011 to 2016. Nutrients, 12(2), 428.

- Footnote 35

-

Potvin Kent M, Pauzé E, Roy EA, de Billy N, & Czoli C. (2019). Children and adolescents' exposure to food and beverage marketing in social media apps. Pediatric Obesity, 14(6), e12508.

- Footnote 36

-

Demers-Potvin É, White M, Potvin Kent M, Nieto C, White CM, Zheng X, Hammond D, & Vanderlee L. (2022). Adolescents' media usage and self-reported exposure to advertising across six countries: implications for less healthy food and beverage marketing. BMJ Open, 12(5), e058913.

- Footnote 37

-

Chester J, Montgomery K, & Kopp K. (2021). Big food, big tech, and the global childhood obesity pandemic. Center for Digital Democracy.

- Footnote 38

-

Coleman PC, Hanson P, van Rens T, & Oyebode O. (2022). A rapid review of the evidence for children's TV and online advertisement restrictions to fight obesity. Preventive Medicine Reports, 26, 101717.

- Footnote 39

-

Powell LM, Wada R, & Kumanyika SK. (2014). Racial/ethnic and income disparities in child and adolescent exposure to food and beverage television ads across the U.S. media markets. Health & Place, 29, 124–131.

- Footnote 40

-

Fleming-Milici F, & Harris JL. (2018). Television food advertising viewed by preschoolers, children and adolescents: contributors to differences in exposure for black and white youth in the United States. Pediatric Obesity, 13(2), 103–110.

- Footnote 41

-

Rudd Centre for Food Policy & Health. (2022). Targeted food and beverage advertising to Black and Hispanic consumers: 2022 update.

- Footnote 42

-

Potvin Kent M, Hatoum F, Wu D, Remedios L, & Bagnato M. (2022). Benchmarking unhealthy food marketing to children and adolescents in Canada: a scoping review. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice, 42(8), 307-318.

- Footnote 43

-

Potvin Kent M, Hatoum F, Wu D, Remedios L, & Bagnato M. (2022). Benchmarking unhealthy food marketing to children and adolescents in Canada: a scoping review. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada: Research, Policy and Practice, 42(8), 307–318.

- Footnote 44

-

World Health Organization. (2022). Food marketing exposure and power and their associations with food-related attitudes, beliefs and behaviours: A narrative review.