2019 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration

For the period ending

December 31, 2018

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

ISSN 1706-3329

Table of Contents

- Message from the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship

- Introduction

- Canada’s Approach to Immigration

- Temporary Migration to Canada

- Permanent Immigration to Canada

- Canada’s Next Permanent Resident Immigration Levels Plan

- Federal-Provincial/Territorial Partnerships

- Gender and Diversity Considerations in Immigration

- Additional Information

- Annex 1: Section 94 and Section 22.1 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

- Annex 2: Tables

- Annex 3: Temporary Migration Reporting

- Annex 4: Instructions Given by the Minister in 2018

Message from the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship

Throughout our history, Canada has welcomed people from all over the world who have helped to lay the foundations of our country, and who continue to shape our great and diverse nation. Our diversity not only brings social rewards, but a robust and efficient immigration system is also critical to our long-term economic growth.

In 2018, Canada welcomed the highest number of permanent residents since 1913 with over 321,000 admissions. These newcomers arrived as part of a plan to responsibly increase Canada’s immigration levels to nearly one percent of our population. This increase is needed to ensure that our economy continues to grow and can rely on a diverse and skilled supply of labour to compete globally.

We have continued to innovate with pilot programs aimed at strengthening communities across Canada. We introduced a Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot, a community-driven initiative to spread the benefits of economic immigration to smaller centres. As well, the Atlantic Immigration Pilot continues to help designated Atlantic businesses attract and retain international graduates and skilled foreign workers to fill job vacancies so they can grow their companies and the regional economy.

We continue to work with provincial and territorial partners to ensure a collaborative approach to immigration. The Provincial Nominee Program has experienced increases in recent years through higher uptake of this program, reaching an all-time high in 2018.

Also in 2018, Canada became the number one resettlement country in the world, resettling more than 28,000 refugees. We further demonstrated our leadership by engaging with international partners to develop and adopt the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration and the Global Compact on Refugees.

In 2018, Canada issued more than six million visas and electronic travel authorizations to visitors, international students and temporary workers, an increase of more than 5% from the previous year. While we have succeeded in reducing processing times and inventories across many permanent and temporary resident categories, the Department continues to explore options to better serve our clients.

A key element of this Report is a gender based analysis plus of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada’s programs and policies. The Department is committed to ensuring that this remains an integral part of policy and program development.

I am proud of the achievements we have made in delivering on key commitments including helping to create a strong economy, reuniting families and upholding Canada’s humanitarian principles. With this in mind, I invite you to read the 2019 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration, including the multi-year levels plan for 2020 to 2022.

Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship

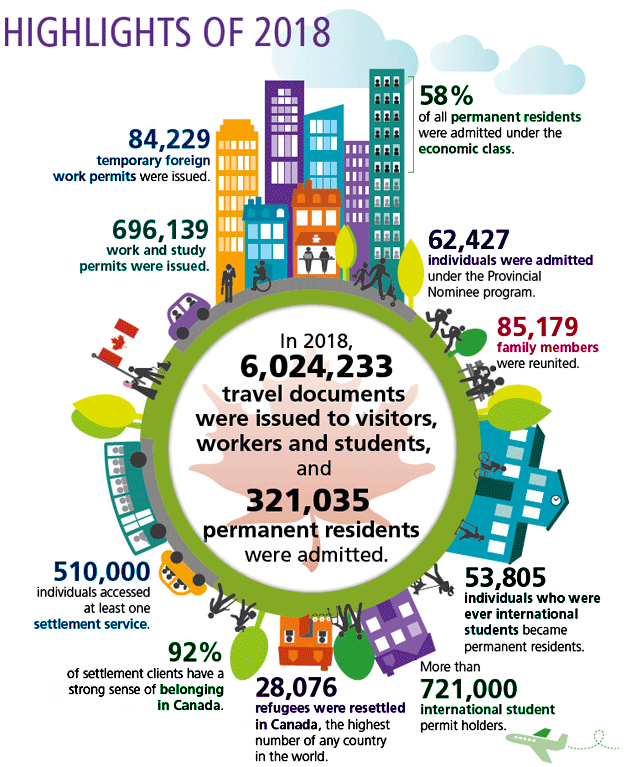

Text version: Highlights of 2018

- In 2018, 6,024,233 travel documents were issued to visitors, workers and students, and 321,035 permanent residents were admitted.

- 84,229 temporary foreign worker permits were issued.

- 696,139 work and study permits were issued.

- 510,000 individuals accessed at least one settlement service.

- 92% of settlement clients have a strong sense of belonging in Canada.

- 28,076 refugees were resettled in Canada, the highest number of any country in the world.

- More than 721 000 international permit holders.

- 53,805 individuals who were ever international students became permanent residents.

- 85,179 family members were reunited.

- 62,427 individuals were admitted under the Provincial Nominee Program.

- 58% of all permanent residents were admitted under the economic class.

Introduction

The Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration provides the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship with the opportunity to inform Parliament and Canadians of key highlights and related information on immigration to Canada. While this report on immigration and its tabling in Parliament is a requirement of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), it also serves to offer key information on the successes that have been achieved as they relate to welcoming newcomers to Canada.

This report sets out information and statistical details regarding temporary resident volumes and permanent resident admissions. It also provides the projected number of upcoming permanent resident admissions in future years, beginning in 2020. In addition, this report contextualizes the efforts undertaken with provinces and territories in our shared responsibility of immigration, and ends with an analysis of gender and diversity considerations in Canada’s approach to immigration.

While the 2019 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration focuses on immigration results that were achieved in 2018, publication takes place in the following calendar year, primarily to allow Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) the opportunity to obtain final information from the preceding calendar year. This timing also ensures inclusion of upcoming immigration levels as required by IRPA.

About data in this report

Admissions data can be found in Annexes 2 and 3, as well as on the Government of Canada’s Open data portal and in the Facts and Figures published by IRCC.

Throughout this report, information is included on prior year admissions, namely 2016 and 2017, along with 2018. Numbers in this report that were derived from IRCC data sources may differ from those reported in earlier publications; these differences reflect typical adjustments to IRCC’s administrative data files over time. As the data in this report are taken from a single point in time, it is expected that they will change slightly over time as additional information becomes available.

Canada’s Approach to Immigration

Canada and immigration

Canada has long benefited from immigration and continues to welcome newcomers for economic, social and humanitarian reasons. While immigration to Canada benefits the country by filling in gaps in the labour market and boosting many sectors of the economy, our immigration system also fosters the reunification of families and provides protection to those at risk, including through the resettlement of refugees from outside Canada. In addition, our immigration system helps maintain the size of the working age population at a time when Canada’s overall population is aging and the need for skilled talent is increasing. Immigration works to counter these challenges, while enriching the social fabric of Canada.

There are different immigration pathways depending on a foreign national’s circumstances and why they wish to visit or stay in Canada. Eligible applicants can enter temporarily for specific reasons, for instance, as visitors, as international students at a designated Canadian educational institution or as temporary workers. For those who wish to remain in Canada on a permanent basis, permanent residency may be granted to select foreign nationals who meet specific criteria for one of the permanent immigration streams among the economic, family, refugee, protected person or humanitarian and compassionate categories. A distinguishing feature of Canada’s immigration system is that it establishes immigration levels for each of these permanent immigration categories on an annual basis.

New permanent residents to Canada may benefit from certain settlement supports to help with their successful integration into Canadian society, such as information and orientation, language training or employment-related services. Such supports funded by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) are offered through service provider organizations across Canada, excluding Quebec.Footnote 1 Once permanent residents meet certain requirements such as residency in Canada, knowledge of Canada and at least one of our official languages, they can become Canadian citizens and participate fully in Canadian society, with all of the responsibilities of being Canadian as well as the opportunities that this offers.

This approach to immigration meets Canada’s domestic objectives of ensuring our continued growth, and has greatly enriched Canadian culture through increased diversity. Moreover, Canada’s approach has proven to be an overall success for decades by meeting our economic, social and humanitarian objectives.

An approach to migration that is highly regarded

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has noted that Canada has the most elaborate and longest-standing skilled labour migration system among OECD countries.Footnote 2 Countries regularly seek information on how Canada’s system works, with the international community looking to Canada to play a leadership role in promoting a well-managed migration system at regional and multilateral fora.

For example, in 2018, Canada engaged with international partners to promote the global expansion of regular migration pathways and resettlement spaces, discussed measures to discourage irregular migration and shared Canada’s experience on various elements of our managed migration system, such as our settlement and integration model. Canada was also recognized for the constructive role it played in the processes to develop the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, the Global Compact on Refugees, and the Global Refugee Sponsorship Initiative. The Compact for Migration was adopted by 152 of 193 United Nations member states in December 2018, while the Compact on Refugees was adopted by 181 member states.

Immigration contributes to Canada’s growth and prosperity

Immigration is a defining feature of our country and our history. Welcoming people from around the world to Canada to visit, study, live and work makes an important contribution to Canada’s economy and has immediate and long-term social benefits. Whether through the temporary migration of workers, students and visitors, the admission of permanent economic immigrants, the reunification of families or the protection of refugees and persons at risk, immigration is a central pillar of Canada’s success story.

Immigrants currently represent 1 in 5 people in Canada,Footnote 3 and over 6 million immigrants have arrived in Canada since 1990. In 2018, Canada welcomed the highest level of permanent residents in recent history, with just over 321,000 admissions. In that same year, Canada also became the number one resettlement country in the world, resettling over 28,000 refugees.

Temporary residents contribute economically and socially to Canada

Canada facilitates the entry of temporary residents, comprised of visitors, foreign workers and students. In 2018, a full 6,024,233 visas and electronic travel authorizations were issued to visitors, international students and temporary workers, an increase of 5.2% from 2017.Footnote 4

Once here, workers can support innovation efforts in Canada and help Canadian firms to grow and prosper, which leads to more jobs for Canadians and a stronger economy for all. Specific industries, including some agricultural sectors, rely heavily on foreign workers during peak seasons.

Important contributions are made by foreign nationals with in-demand talent who come to Canada on a temporary basis, including through programs such as the Global Skills Strategy. Such initiatives make it easier for Canadian businesses to quickly attract the temporary foreign talent they need through a fast and predictable process.

Increasingly, many of these temporary workers are transitioning to permanent residence. For example, in 2018, Canada admitted as permanent residents 56,369 individuals who had previously held a work permit.

Canada’s International Student Program has also seen great demand in recent years. Canada’s standing as a destination of choice for international students has improved in the past few years, ranking in the top 4 international study destinations in 2018, up from seventh place in 2015. In 2018, there were more than 721,000 international students with valid study permits in Canada at all levels of study. Of this total, over 356,000 study permits were issued to international students in 2018, up 13% from 2017. The increases in the number of post-secondary international students to Canada since 2008 represents relatively rapid growth as compared with other OECD countries.Footnote 5

Moreover, 53,805 individuals who ever held a study permit in Canada were admitted as permanent residents, a 20% increase from 2017. Of these, 10,949 held their study permit in 2018, with the majority entering as economic immigrants.

A selection system tailored to meet Canada’s economic needs

While many jobs are filled by Canadians, labour market gaps remain. For this reason, the largest share of newcomers to Canada arrive through the economic class. For example, economic resident admissions accounted for 58% of the 321,035 permanent residents admitted to Canada in 2018. Canada works to ensure that candidates with the highest human capital and that meet current economic needs have the opportunity to apply under a system that is fair and responsive.

Prior to the launch of Express Entry in January 2015, applications were paper based, processed on a first-in first out basis, and took 12 to 14 months on average to process. As of the end of 2018, the overall processing time for all categories was 5 months.Footnote 6

Those seeking to apply as permanent residents under the federal skilled worker class, the federal skilled trades class, the Canadian experience class and certain Provincial Nominee Program streams may apply through the Express Entry selection process. This is an expression of interest system that provides the Government of Canada with the means to manage the intake of applications for these programs while also facilitating the selection of individuals who are most likely to succeed in Canada. Candidates who meet the minimum criteria are entered into a pool, awarded points based on information in their profile and ranked by the Comprehensive Ranking System. Candidates with the highest rankings in the pool are invited to apply online for permanent residence following regular invitation rounds.

Immigration – supporting growth in Canada’s workforce

Canada’s population is aging. Those aged 65 and over made up 16.1% of our population in 2015 and are expected to exceed 24% by 2035.Footnote 9 Given this demographic trend, immigration is key to achieving net labour force growth.

The evidence shows that immigrants to Canada are increasingly contributing to the country’s workforce and supporting labour force needs. As an example, from 2006 to 2017, the proportion of landed immigrants of core working age (25–54 years old) who made up Canada’s workforce increased from 21% to 26%.Footnote 10

In 2018, the top 5 invited occupations were: software engineers and designers, information systems analysts and consultants, computer programmers and interactive media developers, financial auditors and accountants, and administrative assistants.Footnote 7 Also in 2018, Canada admitted more than 92,000 new permanent residents through the Express Entry system, an increase of 41% over 2017.Footnote 8

Immigrants selected through federal economic programs have consistently demonstrated the strongest individual outcomes, as measured by factors such as employment and earnings. Between 2012 and 2016, rates of employment for economic class principal applicants 5 years after they landed in Canada have exceeded the Canadian average by at least 13%. Moreover, for this same cohort, at least 53% have enjoyed employment earnings at or above the Canadian average 5 years after landing.Footnote 11

Immigration, a shared responsibility with provinces and territories

The Constitution of Canada enshrines immigration as a shared responsibility between Canada and the provinces. The federal government therefore works cooperatively with provincial and territorial governments on the selection of certain newcomers. Specifically, provinces and territories may nominate eligible candidates as economic class immigrants via the Provincial Nominee Program (PNP). Through this approach, provincial and territorial selection has resulted in a more balanced geographic distribution of permanent labour migrants across the country over the past 2 decades. However, despite these efforts, many regions of Canada continue to face challenges in attracting and retaining newcomers, including regions with specific workforce gaps.

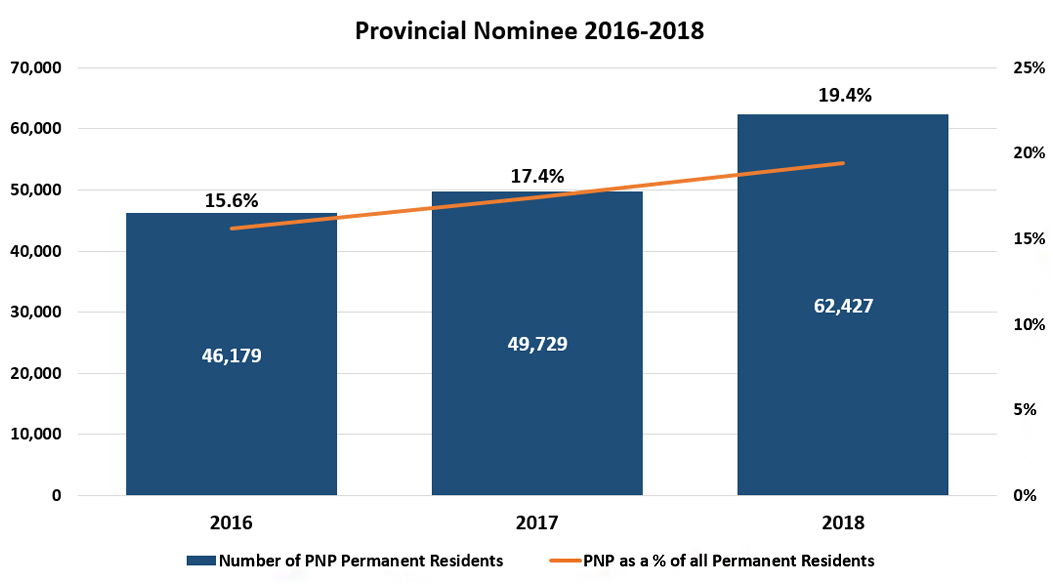

Provincial Nominee Admissions – An increasing component of Canada’s immigration totals

In 2018, the number of permanent residents selected through the PNP reached an all-time high and reflects an ongoing upward trend in the number of permanent residents selected by provinces and territories.

Text version: Provincial nominees (2016–2018)

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of PNP Permanent Residents | 46,179 | 49,729 | 62,427 |

| PNP as a % of all Permanent Residents | 15.6% | 17.4% | 19.4% |

The Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program (AIPP) is an example of what can be accomplished when the Government of Canada, provinces and employers work together to address regional economic development and labour market needs with talented immigrants from around the world. Launched in January 2017, the AIPP is an employer-driven program that enables employers in New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island to hire foreign nationals for jobs that they have not been able to fill locally.

Employers take on responsibility to connect their new worker(s) with the settlement services they need to integrate and thrive in their new homes, such as language training. Employers also take on responsibility for ensuring their workplace is welcoming for newcomers, such as by offering diversity training. So far, over 1,700 employers have participated in the pilot.

As of December 31, 2018, more than 1,400 persons (principal applicants, their spouses and dependants) were granted permanent residence under the pilot,Footnote 12 and more than 2,400 graduates and skilled immigrants received job offers, tailored settlement plans and endorsement from an Atlantic province to submit an application to immigrate to Canada.

Communities are welcoming

Canada’s approach to settlement and integration is also a distinguishing feature of the Canadian immigration system. Its success is due to the strong partnerships that have been established with settlement service providers across the country. Successful integration involves a “whole of society” approach that connects Canadians and newcomers, and helps them reach their economic and social potential. All permanent residents and protected persons are eligible for a range of federally funded settlement services up to the time they become citizens.

With various pre- and post-arrival settlement services available for newcomers and their families through IRCC-funded programs and services, Canada has ensured that overall integration outcomes of newcomers, along with their children, are better than in most other member countries of the OECD.Footnote 13 Canada has been recognized internationally as being at the forefront of testing new, holistic approaches to manage labour migration and to link it with settlement services.

Canada continues to deliver high-quality pre-arrival, settlement and resettlement services for newcomers. Through contribution agreements, service provider organizations, such as immigrant-serving agencies, social service organizations and educational institutions, are allocated funds to provide settlement services to newcomers under 6 main areas (Needs Assessments and Referrals, Information and Orientation, Language Assessments, Language Training, Employment-Related Services and Community Connections), as well as support services such as translation to facilitate access to IRCC-funded settlement services.Footnote 14 In addition, the Settlement Program specifically supports Francophone minority communities through the initiatives announced in the Action Plan for Official Languages 2018–2023, including the development and consolidation of a Francophone integration pathway in collaboration with stakeholders in the Francophone settlement sector.

Pre-arrival services directly connect clients with the information and services they need through a streamlined, easy-to-navigate process while offering general, regional and occupation-specific employment services to boost job prospects for newcomers. In 2018, almost 37,500 clients accessed pre-arrival services.

In 2018, over 510,000 clients accessed at least 1 settlement service. Overall, the Settlement Program has seen a 13.5% increase in unique clients since 2017. Of these clients, 56% were female while 44% were male. Furthermore, 81% of clients accessing services were 18 years of age and older. Information and orientation services had the highest number of unique clients in 2018 at 412,000, while the largest proportion of Settlement Program spending is on language training. IRCC also funds indirect services that support the development of partnerships, capacity building and the sharing of best practices among settlement service providers.

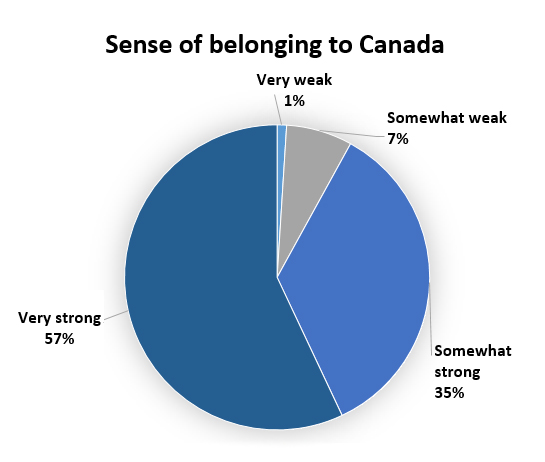

Sense of belonging to Canada

Text version: Sense of belonging to Canada

| Very weak | 1% |

|---|---|

| Somewhat weak | 7% |

| Somewhat strong | 35% |

| Very strong | 57% |

Source: IRCC Annual Outcomes Survey, Settlement Program Clients, 2018

The goal of integration is to encourage immigrants and refugees to be fully engaged in the economic, social, political and cultural life of Canada. The Department assesses the settlement outcomes of users of IRCC-funded programs through various initiatives including an annual outcomes survey. The 2018 survey findings highlight that 84% of survey respondents were participating in the labour market, and 92% had a very strong or somewhat strong sense of belonging to Canada.Footnote 15

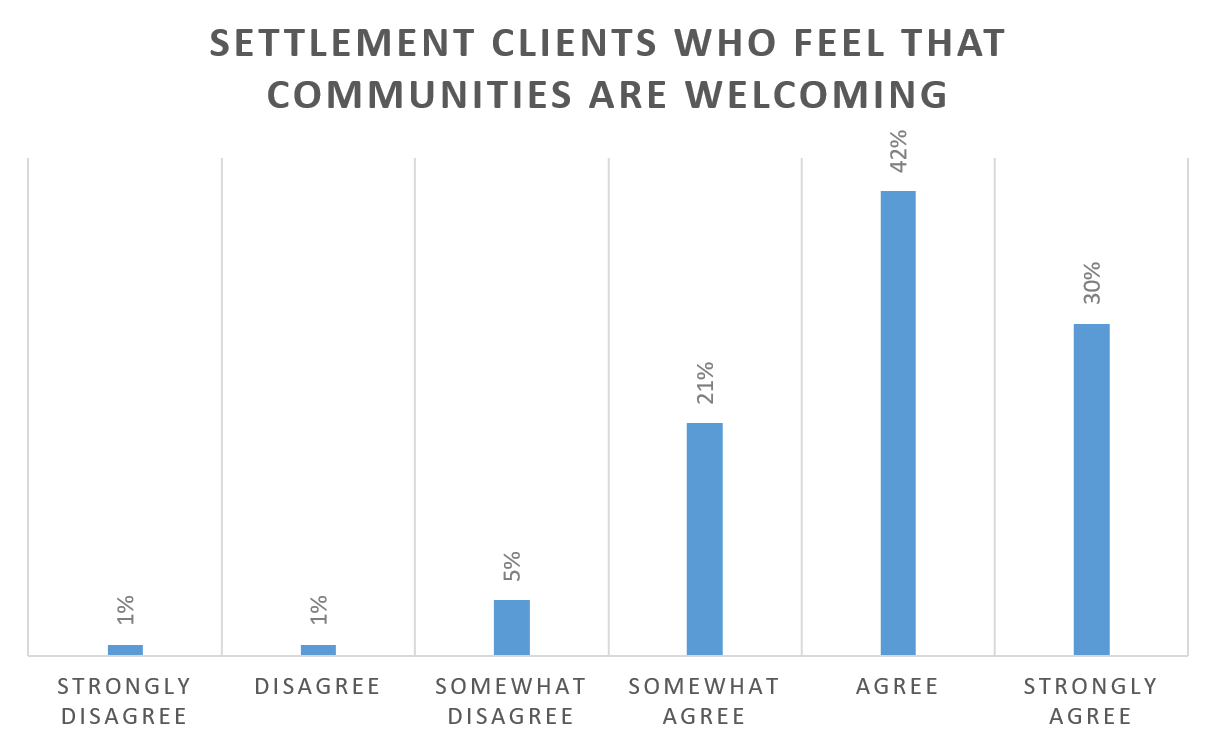

Furthermore, services funded through Canada’s Settlement Program are delivered in collaboration with all levels of government, civil society and the private sector. This promotes a sense of shared community responsibility to be welcoming and responsive to newcomers’ ongoing and emerging needs, and encourages the sharing of newcomers’ wealth of talents and expertise. The recent survey also showed the degree to which newcomers feel welcomed by their local communities.

Settlement Clients who feel that communities are welcoming

Text version: Settlement Clients who feel that communities are welcoming

| Strongly disagree | 1% |

|---|---|

| Disagree | 1% |

| Somewhat disagree | 5% |

| Somewhat agree | 21% |

| Agree | 42% |

| Strongly agree | 30% |

Source: IRCC Annual Outcomes Survey, Settlement Program Clients, 2018

The Francophone Immigration Strategy

Pre-arrival services – ConnexionsFrancophones.ca

To better connect French-speaking permanent residents to Francophone communities, IRCC committed $11 million over 5 years to develop a collaborative model of pre-arrival service provision for French-speaking newcomers. La Cité was designated as the project lead, in partnership with 4 regional organizations that will provide regional information. As of January 2019, ConnexionsFrancophones.ca is the new one-stop shop portal for francophone pre-arrival services.

Following the 2017 Evaluation of the Immigration to Official Language Minority Communities Initiative that offered recommendations on program improvements, on March 13, 2019, a new Francophone Immigration Strategy was launched that builds on new and existing initiatives, including those funded within Canadian Heritage’s Action Plan for Official Languages 2018–2023 (Action Plan). The Action Plan sets aside $40.8 million over 5 years to improve horizontal coordination and accountability for Francophone immigration and official languages and to support the consolidation of the Francophone integration pathway. This pathway seeks to strengthen the settlement, resettlement and integration of French-speaking newcomers and to foster sustainable connections between these newcomers and Francophone communities outside Quebec. Initiatives under the strategy include the provision of official language training adapted to the needs of French-speaking newcomers across the country who are settling in a minority context, capacity building within the Francophone settlement sector, and the creation of welcoming Francophone communities. The Welcoming Francophone Communities Initiative, a community-based 3-year pilot project, aims to support targeted communities by allowing them to create an environment in which French-speaking newcomers will feel welcome and integrate into Francophone minority communities. By the end of March 2019, a total of 14 communities were identified: 3 in Ontario and 1 in every other jurisdiction, except Quebec.

Looking ahead

The global environment is evolving more rapidly than ever, introducing potentially significant changes to the labour market, from the way people work to the types of skills in demand and the integration of new technologies. Canada’s future economic success will depend, in part, on an immigration system that helps ensure that people with the right skills are in the right place, at the right time, to meet evolving labour market needs. Moreover, for immigration to be a continuing success, Canada’s approach will have to address factors such as labour market requirements, the impacts of automation, as well as region- and sector-specific needs. Given this, Canada is working to ensure that an evidence-based understanding of evolving labour market needs informs its approach to immigration.

Immigration has strengthened, and will continue to strengthen Canada as it helps to keep our country globally competitive by promoting innovation and economic growth through its support of diverse and inclusive communities.

Temporary Migration to Canada

Temporary residents are permitted admission under 3 scenarios: as visitors to Canada (through the issuance of an electronic travel authorization [eTA], or a temporary resident visa [TRV], unless exempt); as temporary workers under the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) and the International Mobility Program (IMP); or, as international students. Entries by visitors, temporary workers and international students have shown steady year-over-year increases in the recent past.

The charts below show the number of authorizations and permits issued to temporary residents from 2016 to 2018:

Work and Study Permits issued 2016 - 2018

Text version: Work and Study Permits issued 2016–2018

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TFWP | 78,454 | 78,523 | 84,229 |

| IMP | 207,625 | 223,160 | 255,034 |

| International Students | 264,625 | 315,859 | 356,876 |

Former international students settled permanently, now creating jobs in Canada’s tech industry

ApplyBoard is a company that operates an online app to help students from around the world find and apply to universities, colleges and high schools in Canada and the United States. It uses algorithms to match students to the programs they are most qualified for, based on their academic background, desired course of study and financial means. ApplyBoard was launched in 2015 by 3 brothers who moved to Canada for post-secondary education and then applied for permanent residence in Canada through the Start-up Visa Program. With approximately 200 employees around the world, ApplyBoard has experienced tremendous growth, having reached more than half a million students.

Visitors

Improved access for biometrics requirements

Since July 31, 2018, unless exempted, nationals from countries in Europe, Africa and the Middle East are required to provide biometrics when applying for a visitor visa, a work or study permit, or permanent residence. As of December 31, 2018, this extended to foreign nationals from countries in Asia, Asia Pacific and the Americas. To accommodate travellers who wish to come to Canada, 160 visa application centres operate in 108 countries.

Facilitating visitors’ travel to Canada is achieved through the issuance of TRVs and eTAs.Footnote 16 In 2018, a total of 1,898,324 TRVs and 4,125,909 eTAs were approved for visitors. The average processing time for TRV applications was 20 days, and 65% were processed within the service standard of 14 days. In addition, 99% of eTAs were approved within the standard processing time of 72 hours, the majority of which were approved within minutes of being submitted.Footnote 17

TRVs and eTAs issued 2016 - 2018

Text version: TRVs and eTAs issued 2016–2018

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| eTAs | 2,605,077 | 4,109,918 | 4,125,909 |

| TRVs | 1,347,898 | 1,617,222 | 1,898,324 |

Temporary Foreign Worker Program

In 2018, a total of 84,229 work permits were issued under the TFWP, which assists employers in filling genuine labour market requirements when qualified Canadians and permanent residents are not available. Admissions in this program include agricultural workers and other workers who require a Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA). The number of work permits issued in 2018 represents a 7.3% increase from the 78,523 work permits issued in 2017.

International Mobility Program

Global Skills Strategy

Launched in 2017, the Global Skills Strategy continued to support Canada’s economy by helping Canadian businesses attract global talent. After two years, 21,000 people have come to Canada under this strategy, including nearly 17,000 highly skilled workers.

In addition, 255,034 work permits were issued under the IMP, which are exempt from an LMIA as they advance Canada’s broader social, cultural and economic interests and competitive advantage. Under the IMP, some of the exempt categories include temporary workers under international agreements, eligible graduating international students and the Mobilité francophone program which exempts French‑speaking workers undertaking skilled work outside of Quebec. From the beginning of June 2016 to the end of September 2019, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) and the Canada Border Services Agency approved 3,316 work permit applications and 678 work permit extension applications under Mobilité francophone. In 2018, a total of 82% of work permit applications submitted overseas were finalized within the established service standard of 2 months.

International students

Student Direct Stream

The Student Direct Stream is available to students applying for a study permit who are legal residents of China, India, Vietnam and the Philippines. It was recently expanded to Pakistan, Morocco and Senegal. Students with the financial resources and language skills required to succeed academically in Canada will benefit from faster processing times, with most applications processed within 20 calendar days.

International students have cited Canada’s generous study-related work authorizations as what makes the country an attractive study destination. In 2018, Canada issued 356,876 study permits to international students at all levels of study, and 91% of study permit applications submitted overseas were finalized within the established service standard of 2 months. Over the past decade, the number of post-graduation work permit holders in Canada has increased from 95,455 in 2014 to 186,055 in 2018.

Transitions from temporary worker and international student status to permanent residence

In 2018, a total of 95,283 individuals who ever held a work permit were admitted to Canada as permanent residents. As well, a total of 53,805 individuals were admitted in 2018 who had ever held a study permit as an international student in Canada. The following graph highlights those individuals whose study or work permits were held in the same year that they became permanent residents from 2016 to 2018.Footnote 18

Transition from temporary worker and international student status to permanent residence

Text version: Transition from temporary worker and international student status to permanent residence – 2016 – 2018

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temporary Foreign Workers | 41,637 | 49,614 | 56,369 |

| International Students | 8,271 | 9,410 | 10,949 |

In addition, 22,897 individuals who applied through Express Entry and were invited to apply for permanent residency had received extra points because they had a Canadian educational credential.Footnote 19

Permanent Immigration to Canada

Permanent resident admissions

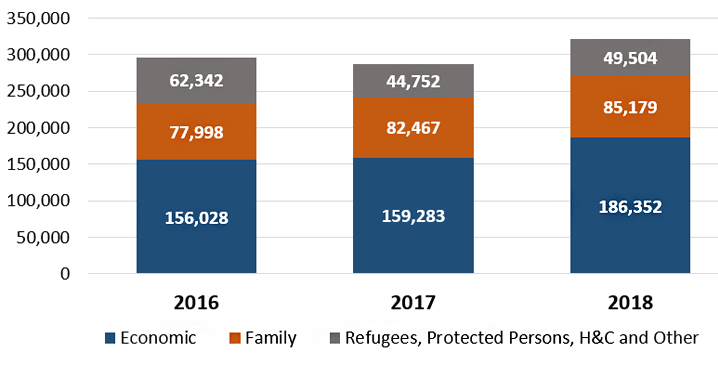

Since 2016, admissions of permanent residents have increased steadily year over year in the economic and family classes, while admissions under the refugee, protected person, humanitarian and compassionate (H&C) and other categories have varied. The breakdown by year is provided in the chart below.Footnote 20

Permanent residents admitted to Canada (2016–2018) Footnote 21

Text Version of: Permanent residents admitted to Canada (2016–2018)

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | 156,028 | 159,283 | 186,352 |

| Family | 77,998 | 82,467 | 85,179 |

| Refugees, Protected Persons, H&C and Other | 62,342 | 44,752 | 49,504 |

Canada admitted 321,035 permanent residents in 2018. This is the highest number of permanent residents admitted to Canada since 1913.

Economic class admissions in 2018

The economic immigration class remains the primary source of permanent resident newcomers to Canada. In 2018, Canada admitted 186,352 permanent residents under economic class programs, representing 58% of all admissions. This was within the target range of 169,600 to 188,500. This class is comprised of 6 economic-focused immigration streams, 3 of which accounted for a large majority (87%) of all economic class permanent resident admissions in 2018: federal high skilled (over 40%), provincial nominees (33%) and Quebec skilled workers (13%).Footnote 22

Canada’s federal high skilled economic programs are aimed at attracting skilled workers. For example, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) attracts other qualified skilled workers with foreign work experience through the federal skilled worker class. The federal skilled trades class is focused on those who are qualified in a specific skilled trade. IRCC also selects eligible applicants who already have Canadian work experience through the Canadian experience class. Together, these immigration streams are directed to those with specific work skills that would contribute to the Canadian workforce.

Canada also operates 2 smaller federal programs. First, the Start-Up Visa Program for innovative foreign entrepreneurs who have the potential to launch high-growth start-ups in Canada. As of early 2019, over 190 businesses were started under this program. Second, the self-employed persons class for business immigrants who could make a significant contribution to the cultural or artistic life of Canada.

In addition, Canada works cooperatively with provinces and territories on the selection of certain skilled foreign nationals. The Provincial Nominee Program allows provinces and territories, other than Quebec, to nominate individuals who express an interest in locating to that province or territory. These individuals are considered possible candidates who will contribute to the economic development of that province or territory.

For those who wish to be admitted as an economic class permanent resident and reside in Quebec, decision-making on selection is completed by the province of Quebec for skilled workers. This approach allows Quebec to apply its own standards and processes, and ensures that Quebec selects candidates who are considered to be most likely to successfully settle and integrate in that province. However, individuals selected by the province of Quebec must still meet certain requirements set by Canada (for example, admissibility requirements).

Pilot programs support successful economic admissions

Pilot programs support federal and provincial economic class immigration priorities. For example, the Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program (AIPP) and the Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot aim to test new approaches and partnerships to address demographic challenges, fill labour gaps and support economic growth in Canada’s smaller centres.

The AIPP, launched in 2017 and extended to December 2021, has to date produced positive results.Footnote 23 In 2018, more than 1,400 people were admitted to Canada through the AIPP. In spring 2019, the Department announced 11 communities located in Ontario and across Western Canada to participate in the Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot. Each pilot partners the federal government with local economic development organizations to test a community-driven model of attracting and retaining new immigrants in smaller centres. It is expected to generate new admissions beginning in 2020.

In 2018, a total of 17,821 persons were admitted under caregiver classes, which includes admissions under 2 pilot programs: the caring for children class and the caring for people with high medical needs class, and the Live-in Caregiver Program. Two new pilot programs, the Home Child Care Provider Pilot and Home Support Worker Pilot, were introduced in 2019 to replace the caring for children and the caring for people with high medical needs classes. The new pilot programs support caregivers’ economic establishment as permanent residents by offering a clearer transition from temporary to permanent status. They also reduce worker vulnerability and prolonged family separation.

In 2019, the Government also announced the Agri-Food Immigration Pilot, which will aim to attract and retain experienced, non-seasonal workers to help address labour needs in the Canadian agri-food sector. IRCC will begin processing applications in 2020.

Family reunification admissions in 2018

Canada reunited 85,179 family members in 2018. Of these, 67,153 were admitted as spouses, partners and children; the other 18,026 were admitted under the parents and grandparents category. All of these totals were within 2018 ranges.

IRCC’s continued commitment to faster processing times and a better managed application inventory resulted in faster reunification for families in 2018. The backlog of applications for parents and grandparents was reduced from 167,000 individuals in 2011 to 25,800 individuals in 2018, representing an 84% decrease.Footnote 24 Also, processing times for sponsoring parents and grandparents were reduced significantly; new applications can expect to be processed within 20 to 24 months.

Permanent residents admitted in the family reunification category 2016–2018Note *

Text version: Permanent residents admitted in the family class category 2016–2018

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Family Reunification | 77,998 | 82,467 | 85,179 |

| Spouses, Partners, Children and Other | 60,955 | 61,973 | 67,153 |

| Parents and Grandparents | 17,043 | 20,494 | 18,026 |

Francophone immigration to Canada

Immigration contributes to Canada’s vitality by adding newcomers and diversity to the country’s communities, including Francophone minority communities.

The Government of Canada is committed to supporting the vitality of these communities and increasing the proportion of French-speaking immigrants settling outside of Quebec, working toward a target of 4.4% of all immigrants by 2023. In 2018, French speakers accounted for 1.83% (4,929) of all permanent residents admitted outside of Quebec, an increase from the 4,137 admitted in 2017.Footnote 25

Efforts to increase Francophone immigration, including through the introduction of bonus points for French language skills in Express Entry, are expected to contribute to increased admissions of French speakers outside of the province of Quebec. In 2018, a total of 4.5% of invitations to apply through Express Entry had been issued to French-speaking candidates compared to 2.9% in 2017.

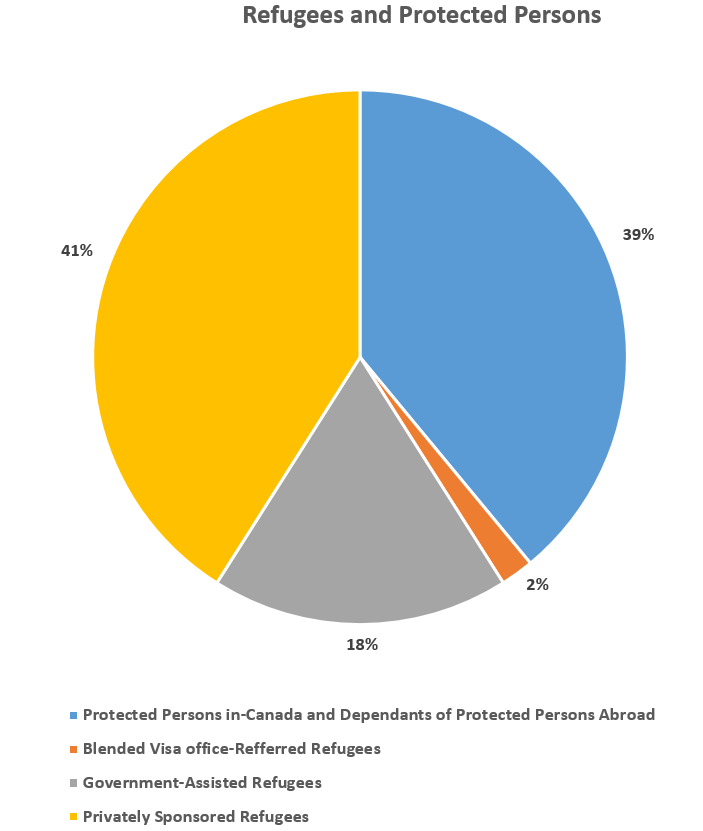

Refugee, protected person and humanitarian and compassionate admissions in 2018

In 2018, a total of 45,758 refugees and protected persons were admitted as permanent residents. This exceeded IRCC’s target of 43,000. In addition, a total of 3,746 were admitted on H&C and public policy grounds. For more information please consult Annex 2, tables 3 and 4.

Protected persons, refugees and H&C admissions 2016–2018

Text version: Protected persons, refugees and humanitarian and compassionate admissions 2016–2018

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protected persons, Refugees and H&C | 62,342 | 44,752 | 49,504 |

Refugees and protected persons

In 2018, a total of 28,076 refugees were resettled to Canada, representing the highest number of refugees resettled of any country in the world that year.Footnote 26

In response to a December 2017 urgent appeal from the UNHCR, Canada committed to resettling 100 refugees evacuated from Libyan migrant detention centres to Niger. This group included victims of human smuggling. In addition, Canada is one of the few countries to resettle refugees directly out of Libya, having resettled more than 150 persons in 2018.

Of all refugees resettled in 2018, a total of 18,763 were privately sponsored, 8,156 were government assisted and 1,157 were admitted under the Blended Visa Office-Referred Refugee Program, which enables sponsorship groups and government to jointly support resettled refugees identified by the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR). Moreover, 10,999 of these resettled refugees were 17 years old or under.

In addition, 17,682 individuals obtained permanent residence under the protected persons in Canada and dependants abroad category. This category is comprised of protected persons and their dependants abroad who have received protected status in Canada.

Refugees and protected persons

Text version: Refugees and Protected Persons

| Category | % |

|---|---|

| Protected Persons in-Canada and Dependants of Protected Persons Abroad | 39% |

| Blended Visa Office-Referred Refugees | 2% |

| Government-Assisted Refugees | 18% |

| Privately Sponsored Refugees | 41% |

Global Refugee Sponsorship Initiative

Canada is contributing to international refugee protection efforts by sharing 40 years of experience with private refugee sponsorship through the Global Refugee Sponsorship Initiative (GRSI). IRCC leads Canada’s efforts, in cooperation with a partnership involving the United Nations Refugee Agency, the University of Ottawa and international philanthropic organizations.

Launched in the fall of 2016, the GRSI has 3 goals: increase and improve global refugee resettlement by engaging private citizens, communities and businesses in resettlement efforts; strengthen local host communities that come together to welcome newcomers; and improve the narrative about refugees and other newcomers. Since the launch, Canada has been working closely with 6 countries that have introduced or are piloting refugee sponsorship programs: United Kingdom, Argentina, Ireland, Germany, Spain and New Zealand.

The GRSI is recognized as an international best practice and has been enshrined in the Global Compact on Refugees, endorsed by the United Nations in December 2018.

Asylum claimants

In 2018, Canada received over 55,000 in-Canada asylum claims, the highest annual number received on record. Of these, approximately 35% were made by asylum claimants who crossed the Canada-U.S. border between designated ports of entry.Footnote 27 To respond to these pressures, Budget 2018 provided $173.2 million over 2 years, starting in 2018–2019, to support security operations at the border and to increase decision-making capacity at the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada. In addition, a deputy minister-level Asylum System Management Board was established in the spring of 2018 to improve coordination between organizations responsible for the asylum system.

In addition, Budget 2019 invested $1.18 billion over 5 years, beginning in 2019–2020, and $55 million per year ongoing to further increase the capacity of the asylum system to process up to 50,000 cases by 2021 and to support the implementation of a Border Enforcement Strategy. These investments build on those made in Budget 2018 to effectively manage Canada’s border and asylum system. They also allowed for the expansion of a pilot project to increase efficiencies in the pre-hearing process for asylum claims (the Integrated Claim Analysis Centre). Budget 2019 also earmarked $283 million over 2 years, beginning in 2019–2020, to address additional funding pressures on the Interim Federal Health Program, driven by the increased numbers of asylum claimants. The program provides health care to refugees and asylum seekers to promote better public health outcomes for both Canadians and those seeking protection in Canada.

Recognizing that provinces have faced pressures associated with the influx of irregular migrants, on June 1, 2018, the Government of Canada pledged an initial $50 million to assist the provinces that have borne the majority of costs associated with the increase in asylum claimants. This was followed by the establishment of the Interim Housing Assistance Program in early 2019, to support provinces and, if necessary, municipalities that incurred extraordinary interim housing costs in 2017 through 2019. As of September 2019, the government has provided provinces and municipalities with over $370 million to address pressures resulting from the increase in asylum claims. Maintaining border integrity, ensuring public safety and security, and treating asylum claimants with dignity and compassion continue to be key guiding principles for the Government of Canada.

Abdul Musa Agha, St. Catharines, Ontario, arrived in Canada with his family in January 2016

When Abdul Musa Agha and his family first arrived they lived in Port Colborne, Ontario. Their sponsors helped them a great deal, for example, by providing rides to various appointments, showing them where to buy things, and helping them learn English. After 6 months, Abdul found work with a barber, his former profession, in St. Catharines. They moved to that city, where he worked while continuing to learn about business in Canada and improving his English.

Abdul has now been operating his own barbershop, Musa’s Final Touch, in St. Catharines for 1 year. He employs 2 barbers and 1 customer service representative. Business is good and he says he is living the Canadian dream. People are friendly, and in his words, “Canada is the place for everyone who has a dream.”

Humanitarian and compassionate and other

The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act authorizes the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship to grant permanent residence status to individuals and their families who would not otherwise qualify under an immigration category. These discretionary provisions for humanitarian and compassionate or public policy considerations provide the flexibility to approve deserving cases that come forward. In 2018, a total of 3,746 people were admitted to Canada for humanitarian and compassionate and public policy considerations. This category accounted for 1.2% of all permanent residents.

Abdulfatah Sabouni, Calgary, Alberta, arrived in Canada in January 2016

“I feel so happy and safe to be in Calgary. I lost everything to the war. I had manufacturing, staff, stores, customers in Syria. Canada has a good reputation and freedom. My family has been in the soap business for more than 100 years so it was a dream to start one.

I went to school for one year to study English. It was hard at first but I’m getting better now. I am also working hard to run my business. I opened an Aleppo Savon factory and store in southeast Calgary in January 2018, followed by 2 retail locations in Calgary malls, in October and December.

Canada helped me realize that dream, support from people has been amazing. It’s great to meet and work with different communities.”

Canada’s Next Permanent Resident Immigration Levels Plan

The levels plan determines how many permanent residents will be admitted to Canada for the next calendar year. Every year, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) sets targets and ranges for the total number of permanent residents admitted into the country, as well as the number for each immigration category.

Since 2017, the Department has used a rolling multi-year levels plan, whereby a new third year is added annually with the tabling of the levels plan. The 2 outer years project notional targets and ranges. The levels plan is developed in consultation with provinces and territories, the public and stakeholder organizations. IRCC selects these immigrants for their economic contribution, to reunite families and in support of humanitarian needs.

The Government of Canada’s permanent resident immigration levels plan is as follows.

2020–2022 Immigration Levels Plan

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Projected admissions – Targets | 341,000 | 351,000 | 361,000 | |||

| Projected admissions – Ranges | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High |

| Federal economic, provincial/territorial nominees | 161,600 | 187,400 | 165,600 | 191,500 | 169,600 | 195,900 |

| Quebec-selected skilled workers and business | 24,900 | 25,600 | To be determined | To be determined | To be determined | To be determined |

| Family reunification | 84,500 | 96,000 | 87,000 | 98,000 | 87,000 | 98,000 |

| Refugees, protected persons, humanitarian and compassionate and other | 49,000 | 61,000 | 50,500 | 62,000 | 52,000 | 63,000 |

| Total | 320,000 | 370,000 | 330,000 | 380,000 | 340,000 | 390,000 |

Federal-Provincial/Territorial Partnerships

Immigration: A joint responsibility

Immigration is a joint federal-provincial-territorial (FPT) responsibility and requires a collaborative approach to share the benefits of immigration across Canada.

Overall, the federal government is responsible for setting national immigration levels, for defining immigration categories, for granting protected person status to refugee claimants within Canada and for reuniting families. The federal government also admits all foreign nationals to the country, including temporary and permanent residents, in addition to establishing eligibility criteria for settlement programs in the provinces and territories, with the exception of Quebec.

Bilateral engagement

Bilateral framework immigration agreements define the roles and responsibilities of Canada and the province/territory to support collaboration on immigration issues. These agreements (either broader framework agreements or agreements establishing Provincial Nominee Program authorities only) are in place with 9 provinces and 2 territories (excluding Nunavut and Quebec). Under the Provincial Nominee Program, provinces and territories have the authority to nominate individuals as permanent residents to address specific labour market and economic development needs.

Under the Canada-Québec Accord relating to Immigration and Temporary Admission of Aliens, Quebec has exclusive responsibility for the selection of economic immigrants destined for that province and can establish its own selection criteria for those immigrants. Quebec also has selection authority over resettled refugees, but shares the overall responsibility with the federal government, which determines who is a refugee and identifies refugees for resettlement. The province has sole responsibility for delivery of settlement and integration services within Quebec, and receives an annual grant from the federal government. Quebec also has the authority to set its own immigration levels, within the parameters of the Canada-Quebec Accord.

Table 3 in Annex 2 presents the breakdown of permanent residents admitted in 2018 by province or territory of destination and immigration category.

Federal/Provincial/Territorial Forum of Ministers Responsible for Immigration

The FPT Forum of Ministers Responsible for Immigration meets in-person annually to discuss issues and priorities of interest across jurisdictions. Multilateral tables at the deputy minister, assistant deputy minister and director general level provide strategic direction and oversight to a number of themed working groups. The Forum’s FPT Vision Action Plan for Immigration (2016–2019) is being renewed to set multilateral priorities for 2020–2023.

Gender and Diversity Considerations in Immigration

What is GBA+?

From GBA to GBA+

The “plus” in GBA+ acknowledges that GBA goes beyond biological (sex) and socio-cultural (gender) differences.

People’s lives are multi-dimensional and complex, and intersectionality helps us understand the nuances of human lives and lived experiences.

GBA+ is an intersectional analytical process used to examine how various intersecting identity factors may impact the effectiveness of government initiatives. It involves examining disaggregated data and research, and considering social, economic and cultural conditions and norms.

The Government of Canada has been committed to using GBA+ in the development of policies, programs and legislation since 1995. GBA+ provides federal officials with the means to attain more equitable results for people by being more responsive to specific needs and ensuring government policies and programs are inclusive and barrier free.

GBA+ and experiences of immigration

What is gender equality?

Gender equality is a fundamental human right. It is about equitable access to resources such as education, health care and employment as well as equitable representation in all social, political and economic spheres of decision-making, regardless of one’s gender.

Canada recognizes that an individual’s experience of migration may differ depending on the interaction and influence of identity factors such as (but not limited to) sex, age, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity and/or gender expression.Footnote 28 The importance of intersectional factors is also increasingly recognized in the international context by partner organizations such as the International Organization for Migration (IOM), the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the United Nations.

GBA+ is used to better understand how persons with different identities, backgrounds and experiences may be affected by Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) policies and programs. In 2018, IRCC applied GBA+ to its programs and policies to assess the different immigration needs and challenges of diverse population groups. Through this report, IRCC highlights its work in 2018 to identify and address barriers caused by gender and intersectional gaps impacting individuals such as survivors of gender-based persecution in conflict zones and members of LGBTQ2 communities, and to improve settlement services for newcomers—including women—that account for their backgrounds and migration experiences.

Below are key initiatives in 2018 that highlight how IRCC has implemented measures to become more responsive to particular gender and diversity groups.

Changes to the Policy Regarding Excessive Demand on Health and Social Services – Encouraging Inclusiveness and Diversity

In June 2018, IRCC changed its medical inadmissibility policies to better align the selection of newcomers with Canadian values of inclusion and diversity. Under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), applicants may be found inadmissible if they have a health condition that poses an excessive demand on health or social services.

The policy on excessive demand was initially designed to prevent undue strain on Canadian health care. However, it may have inadvertently resulted in stigmatizing persons with disabilities, with the unintended consequence of creating a barrier to migration for individuals wanting to work or study in Canada.

Gender and migration

- Women migrate as much as men. Migration data must be disaggregated by sex and age, and migration policies must take into account how sex and gender shape different migrants’ needs.

- Migration creates empowerment trade-offs for individual women and girls, and between different groups of women and girls.

- Highly skilled women have high rates of migration but many are employed in low-skilled jobs.

- Migration can increase women’s access to education and economic resources, and can improve their autonomy and status.

To address these barriers, the newly updated policy increased the cost threshold of medical inadmissibility to 3 times the Canadian average and modified IRCC’s definition of social services. As a result, fewer applicants with disabilities will be deemed inadmissible on health grounds. This change brings the policy in line with Canadian values on supporting the participation of persons with disabilities in society, while continuing to protect publicly funded health and social services.

Prior to this policy change, approximately 1,000 applicants for permanent and temporary residence in Canada, or an accompanying dependant, were deemed inadmissible for excessive demand because treatment for their health condition was expected to either exceed the cost threshold or impact wait lists. Under section 38(2) of IRPA, Convention refugees and persons in similar circumstances, protected persons, and their family-class sponsored spouses, common-law partners and dependent children are exempted from medical inadmissibility based on excessive demand.

Addressing employment gaps of visible minority immigrant women in Canada

Immigrant women tend to participate less in the labour force compared to immigrant men (and the Canadian-born), and those who do seek employment have less success finding it.Footnote 29

Labour force participation in 2018 (25–54 years)Footnote 30

| Women | Men | |

|---|---|---|

| Immigrant | 77.7% | 91.6% |

| Canadian-born | 86.1% | 90.9% |

Human capital factors such as education and the age of the newcomer at entry to Canada are the best predictors of long term earnings.Footnote 31 A persistent gap in labour market integration exists for women between very recent, recent and established female immigrants and their Canadian-born counterparts.Footnote 32

Recognizing that these challenges exist, in 2018, the Department launched the Visible Minority Newcomer Women Pilot, a 3-year pilot with an investment totalling $31.9 million aimed at improving the employment and career advancement of visible minority newcomer women in Canada (outside Quebec). The pilot being implemented seeks to increase existing, effective services that already serve visible minority newcomer women; establish new partnerships to fund innovative interventions to help visible minority women access the labour market; build capacity in smaller organizations that serve or are led by visible minority women; emphasize digital/online learning; and test and evaluate the effectiveness of employment-related services for visible minority newcomer women.

Welcoming women to technology

Ulrike Bahr-Gedalia has spent the past 15 years earning a reputation as a tireless connector. Of course, as president and CEO of Digital Nova Scotia, that’s her job: Digital Nova Scotia is the key industry association for the province’s $2.5 billion information technology and digital technologies sector.

She recalls that as a newcomer in Halifax looking for work, her first thought was to contact other women. She spoke with a fellow immigrant from Germany who helped her land her first job in the technology field.

Ulrike has herself been a mentor to many since then, and has received numerous leadership awards. She was honoured with the WXN Canada’s Most Powerful Women: Top 100 Award in 2015, 2016 and 2017, and was a recipient of the RBC Top 25 Canadian Immigrant Award in 2015.

“Ulrike’s willingness to reach out to people and help them build networks and get in the door is incredible. We need more women leaders like her for girls and women to look up to.” — Adrienne Power, Development Officer, Faculty of Computer Science, Dalhousie University.

Protecting women and girls at risk

Forced migration and refugees

In 2018, nearly 70.8 million individuals were forcibly displaced worldwide, including 41.3 million internally displaced people, 25.9 million refugees and 3.5 million asylum seekers.

In 2018, a total of 92,400 refugees were resettled to 25 countries (UNHCR).

Available data indicates that about half of the world’s refugee population is made up of women and girls, meaning they represent a significant segment of those fleeing war, violence or persecution in their home countries. IRCC recognizes the disproportionate and unique impact that forced displacement has on women and girls. Through GBA+ analysis, IRCC found that refugee women and girls face increased risks due to their gender, and as such, are at a higher risk of, or have already suffered from, sexual violence and exploitation, physical abuse and marginalization. Within this context and in response to communications with the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), the federal Government committed to resettling an additional 1,000 refugee women and girls from various conflict zones around the world by December 31, 2019.

Updates to the handbook for Resettlement Assistance Program service provider organizations

The Resettlement Assistance Program (RAP) Service Provider Handbook describes in detail the services that service provider organizations (SPOs) funded through the program are expected to deliver to their clients. In 2018, this handbook was updated to include a GBA+/LGBTQ2 lens based on consultations with Canadian LGBTQ2 non-governmental organizations. In particular, the update included the need for a “trauma-informed approach” to ensure that all SPO staff assisting newly arrived government-assisted refugees have the requisite experience and training to best approach clients who may have been persecuted based on their gender identity, gender expression or biological sex. The handbook also includes references to the need for cultural and/or diversity training, such as information on the particular needs and vulnerabilities of LGBTQ2 clients, as well as services and supports available for this clientele. Such training for staff of Resettlement Assistance Program SPOs will be required in 2020.

Reflecting gender considerations in the global compacts

Throughout the 2-year process to develop the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration and the Global Compact on Refugees, Canada advocated for meaningful inclusion of gender responsiveness in the text. This is particularly important given that almost 50% of both the migrant and refugee populations are women and that gender considerations are relevant across both the migration journey and that of forced displacement. In particular, Canada emphasized the importance of recognizing the agency of women migrants, and supporting their empowerment. With respect to the Global Compact on Refugees, Canada was particularly active as a champion of measures to advance gender equality and to address the particular needs and risks faced by women and girl refugees. The international community must now decide how to carry this forward in its implementation of both compacts.

What’s next?

IRCC remains committed to the goals of inclusion and will continue to utilize GBA+ as a tool for evidence-based decision-making. Aligned with other federal departments and agencies, IRCC will work toward an even stronger analysis of intersectional data as it becomes available to increase the Department’s knowledge and understanding of applicants, newcomers and refugees, including—stakeholder views—and to use this data to improve policies and programs.

Additional Information

The Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration fulfills the Minister’s obligations under section 94 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act to table a report in Parliament on specific aspects of Canada’s immigration system; Annex 1 of this report provides details of these obligations. For more information on Canada’s immigration system, please consult the following resources:

- Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports for:

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) Facts and Figures, which provide high-level immigration statistics for Canada. Since 2016, IRCC Facts and Figures have been available on the Open Government Portal.

- The Government of Canada’s Open Data Portal for IRCC, which provides more detailed immigration-related data sets.

Annex 1: Section 94 and Section 22.1 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

The following excerpt from the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), which came into force in 2002, outlines the requirements for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada to prepare an annual report to Parliament on immigration.

Reports to Parliament

94 (1) The Minister must, on or before November 1 of each year or, if a House of Parliament is not then sitting, within the next 30 days on which that House is sitting after that date, table in each House of Parliament a report on the operation of this Act in the preceding calendar year.

(2) The report shall include a description of

- (a) the instructions given under section 87.3 and other activities and initiatives taken concerning the selection of foreign nationals, including measures taken in cooperation with the provinces;

- (b) in respect of Canada, the number of foreign nationals who became permanent residents, and the number projected to become permanent residents in the following year;

- (b.1) in respect of Canada, the linguistic profile of foreign nationals who became permanent residents;

- (c) in respect of each province that has entered into a federal-provincial agreement described in subsection 9(1), the number, for each class listed in the agreement, of persons that became permanent residents and that the province projects will become permanent residents there in the following year;

- (d) the number of temporary resident permits issued under section 24, categorized according to grounds of inadmissibility, if any;

- (e) the number of persons granted permanent resident status under each of subsections 25(1), 25.1(1) and 25.2(1);

- (e.1)any instructions given under subsection 30(1.2), (1.41) or (1.43) during the year in question and the date of their publication; and

- (f) a gender-based analysis of the impact of this Act.

The following excerpt from IRPA outlines the Minister’s authority to declare when a foreign national may not become a temporary resident, which came into force in 2013, and the requirement to report on the number of such declarations.

Declaration

22.1 (1) The Minister may, on the Minister’s own initiative, declare that a foreign national, other than a foreign national referred to in section 19, may not become a temporary resident if the Minister is of the opinion that it is justified by public policy considerations.

(2) A declaration has effect for the period specified by the Minister, which is not to exceed 36 months.

(3) The Minister may, at any time, revoke a declaration or shorten its effective period.

(4) The report required under section 94 must include the number of declarations made under subsection (1) and set out the public policy considerations that led to the making of the declarations.

Annex 2: Tables

Table 1: Temporary Resident Permits and Extensions Issued in 2018 by Provision of Inadmissibility

| Description of Inadmissibility | Provision Under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act | Total Number of Permits in 2018 | Females | Males |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Security (e.g., espionage, subversion, terrorism) | 34 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Human or international rights violations | 35 | 3 | 0 | 3 |

| Serious criminality (convicted of an offence punishable by a term of imprisonment of at least 10 years) | 36(1) | 559 | 37 | 522 |

| Criminality (convicted of a criminal act or offence prosecuted by way of indictment) | 36(2) | 4,122 | 587 | 3,535 |

| Organized criminality | 37 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Health grounds (danger to public health or public safety, excessive demand) | 38 | 9 | 4 | 5 |

| Financial reasons (unwilling or unable to support themselves or their dependants) | 39 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Misrepresentation | 40 | 131 | 34 | 97 |

| Cessation of refugee protection | 40.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Non-compliance with Act (e.g., no passport, no visa, work/study without permit, medical/criminal check to be completed in Canada)Footnote * | 41 | 2,299 | 1,041 | 1,258 |

| Inadmissible family member | 42 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

| Total | 7,132 | 1,706 | 5,426 |

Source: IRCC Enterprise Data Warehouse (Master Business Reporting) as of May 27, 2019

Table 2: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2018 by Top 10 Source Countries

| Rank | Country | Number | Percentage | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | India | 69,973 | 22 | 32,988 | 36,985 |

| 2 | Philippines | 35,046 | 11 | 19,727 | 15,319 |

| 3 | China, People’s Republic of | 29,709 | 9 | 16,564 | 13,145 |

| 4 | SyriaFootnote 33 | 12,046 | 4 | 5,782 | 6,264 |

| 5 | Nigeria | 10,921 | 3 | 5,227 | 5,694 |

| 6 | United States of America | 10,907 | 3 | 5,516 | 5,391 |

| 7 | Pakistan | 9,488 | 3 | 4,653 | 4,835 |

| 8 | France | 6,175 | 2 | 2,860 | 3,315 |

| 9 | Eritrea | 5,689 | 2 | 2,501 | 3,188 |

| 10 | United Kingdom and Overseas territories | 5,663 | 2 | 2,306 | 3,357 |

| Total Top 10 | 195,617 | 61 | 98,124 | 97,493 | |

| All Other Source Countries | 125,418 | 39 | 64,693 | 60,725 | |

| Total | 321,035 | 100 | 162,817 | 158,218 | |

Source: IRCC, Permanent Residents Data as of March 31, 2019.

Table 3: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2018 by Destination and Immigration Category

| Immigration Category | NL | PE | NS | NB | QC | ON | MB | SK | AB | BC | YT | NT | NU | Not Stated | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic | |||||||||||||||

| Federal economic – skilledFootnote 34 | 206 | 86 | 664 | 363 | 0 | 52,864 | 912 | 1,039 | 7,324 | 12,088 | 29 | 28 | 3 | 0 | 75,606 |

| Federal economic – CaregiverFootnote 35 | 52 | 4 | 72 | 16 | 859 | 9,123 | 51 | 255 | 4,066 | 3,257 | 12 | 46 | 8 | 0 | 17,821 |

| Federal economic – BusinessFootnote 36 | 2 | 23 | 6 | 15 | 0 | 310 | 14 | 8 | 49 | 325 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 757 |

| Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program | 173 | 199 | 376 | 661 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,409 |

| Provincial Nominee Program | 604 | 1,628 | 3,471 | 2,746 | 0 | 11,369 | 9,889 | 11,109 | 10,269 | 11,028 | 190 | 124 | 0 | 0 | 62,427 |

| Quebec skilled workers | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24,128 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 24,128 |

| Quebec business immigrants | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4,204 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4,204 |

| Economic Total | 1,037 | 1,940 | 4,589 | 3,801 | 29,191 | 73,666 | 10,866 | 12,411 | 21,708 | 26,698 | 236 | 198 | 11 | 0 | 186,352 |

| Family | |||||||||||||||

| Spouses, partners and children | 175 | 104 | 643 | 376 | 10,473 | 29,180 | 2,256 | 1,522 | 10,306 | 11,545 | 51 | 60 | 13 | 0 | 66,704 |

| Parents and grandparents | 19 | 7 | 75 | 37 | 1,718 | 8,532 | 482 | 456 | 3,513 | 3,174 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 18,026 |

| Family - OtherFootnote 37 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 95 | 151 | 4 | 8 | 117 | 65 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 449 |

| Family Total | 196 | 111 | 720 | 417 | 12,286 | 37,863 | 2,742 | 1,986 | 13,936 | 14,784 | 58 | 67 | 13 | 0 | 85,179 |

| Protected Persons and Refugees | |||||||||||||||

| Protected persons in-Canada and dependants abroad | 18 | 4 | 48 | 20 | 3,148 | 11,829 | 118 | 69 | 1,470 | 951 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 17,682 |

| Blended visa office-referred refugees | 11 | 5 | 131 | 13 | 0 | 604 | 69 | 62 | 80 | 169 | 10 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1,157 |

| Government-assisted refugees | 201 | 51 | 228 | 296 | 1,395 | 3,166 | 447 | 455 | 1,144 | 772 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 8,156 |

| Privately sponsored refugees | 66 | 25 | 231 | 48 | 4,289 | 8,313 | 931 | 496 | 3,015 | 1,336 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 7 | 18,763 |

| Protected Persons and Refugees Total | 296 | 85 | 638 | 377 | 8,832 | 23,912 | 1,565 | 1,082 | 5,709 | 3,228 | 13 | 9 | 4 | 8 | 45,758 |

| Humanitarian and Other | |||||||||||||||

| Humanitarian and otherFootnote 38 | 0 | 0 | 17 | 12 | 811 | 1,971 | 48 | 30 | 670 | 182 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3,746 |

| Humanitarian and Other Total | 0 | 0 | 17 | 12 | 811 | 1,971 | 48 | 30 | 670 | 182 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 3,746 |

| Total | 1,529 | 2,136 | 5,964 | 4,607 | 51,120 | 137,412 | 15,221 | 15,509 | 42,023 | 44,892 | 307 | 279 | 28 | 8 | 321,035 |

| PERCENTAGE | 0.48% | 0.67% | 1.86% | 1.44% | 15.92% | 42.80% | 4.74% | 4.83% | 13.09% | 13.98% | 0.10% | 0.09% | 0.01% | 0.00% | 100% |

Source: IRCC, Permanent Resident Data as of March 31, 2019.

Table 4: Permanent Residents Admitted in 2018Footnote 39

| Immigration Category | 2019 Plan Admission Ranges | 2018 Admissions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | High | Female | Male | Total | |

| Federal economic – Skilled | 72,700 | 78,200 | 35,331 | 40,275 | 75,606 |

| Federal economic – Caregiver | 15,000 | 20,000 | 10,446 | 7,375 | 17,821 |

| Federal economic – Business | 500 | 1,000 | 348 | 409 | 757 |

| Atlantic Immigration Pilot Program | 500 | 2,000 | 642 | 767 | 1,409 |

| Provincial Nominee Program | 53,000 | 57,400 | 29,246 | 33,181 | 62,427 |

| Quebec skilled workers and business immigrants | 27,900 | 29,900 | 13,548 | 14,784 | 28,332 |

| Economic Total | 169,600 | 188,500 | 89,561 | 96,791 | 186,352 |

| Spouses, partners and children | 64,000 | 68,000 | 38,390 | 28,314 | 66,704 |

| Parents and grandparents | 17,000 | 21,000 | 10,776 | 7,250 | 18,026 |

| Family – Other | - | - | 250 | 199 | 449 |

| Family Total | 81,000 | 89,000 | 49,416 | 35,763 | 85,179 |

| Protected persons in-Canada and dependants abroad | 13,500 | 17,000 | 8,449 | 9,233 | 17,682 |

| Blended visa office-referred refugees | 1,000 | 3,000 | 598 | 559 | 1,157 |

| Government-assisted refugees | 6,000 | 8,000 | 4,033 | 4,123 | 8,156 |

| Privately sponsored refugees | 16,000 | 20,000 | 8,732 | 10,031 | 18,763 |

| Refugees and Protected Persons Total | 36,500 | 48,000 | 21,812 | 23,946 | 45,758 |

| Humanitarian and Other | 2,900 | 4,500 | 2,028 | 1,718 | 3,746 |

| Total | 290,000 | 330,000 | 162,817 | 158,218 | 321,035 |

Source: IRCC, Permanent Resident Data as of March 31, 2019.

Table 5: Permanent Residents by Official Language Spoken, 2018

| Immigration Class | English | French | French and English | Neither | Not Stated | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic – Principal applicants | 81,877 | 2,896 | 10,202 | 841 | 37 | 95,853 |

| Female | 35,453 | 1,158 | 4,311 | 195 | 21 | 41,138 |

| Male | 46,424 | 1,738 | 5,891 | 646 | 16 | 54,715 |

| Economic – Partners and dependants | 66,912 | 4,303 | 4,140 | 14,064 | 1,080 | 90,499 |

| Female | 35,886 | 2,436 | 2,457 | 7,085 | 559 | 48,423 |

| Male | 31,026 | 1,867 | 1,683 | 6,979 | 521 | 42,076 |

| Total Economic | 148,789 | 7,199 | 14,342 | 14,905 | 1,117 | 186,352 |

| Female | 71,339 | 3,594 | 6,768 | 7,280 | 580 | 89,561 |

| Male | 77,450 | 3,605 | 7,574 | 7,625 | 537 | 96,791 |

| Family reunification – Principal applicants | 46,204 | 3,475 | 3,526 | 11,933 | 6,201 | 71,339 |

| Female | 26,279 | 2,235 | 1,978 | 7,125 | 3,499 | 41,116 |

| Male | 19,925 | 1,240 | 1,548 | 4,808 | 2,702 | 30,223 |

| Family reunification – Partners and dependants | 5,615 | 772 | 200 | 6,204 | 1,049 | 13,840 |

| Female | 3,292 | 403 | 118 | 3,954 | 533 | 8,300 |

| Male | 2,323 | 369 | 82 | 2,250 | 516 | 5,540 |

| Total Family Reunification | 51,819 | 4,247 | 3,726 | 18,137 | 7,250 | 85,179 |

| Female | 29,571 | 2,638 | 2,096 | 11,079 | 4,032 | 49,416 |

| Male | 22,248 | 1,609 | 1,630 | 7,058 | 3,218 | 35,763 |

| Refugees and protected persons in-Canada – Principal applicants | 12,669 | 1,532 | 992 | 6,996 | 783 | 22,972 |

| Female | 4,120 | 772 | 401 | 3,058 | 371 | 8,722 |

| Male | 8,549 | 760 | 591 | 3,938 | 412 | 14,250 |

| Refugees and protected persons in-Canada – Partners and dependants | 7,452 | 886 | 506 | 12,255 | 1,687 | 22,786 |

| Female | 4,546 | 517 | 296 | 6,851 | 880 | 13,090 |

| Male | 2,906 | 369 | 210 | 5,404 | 807 | 9,696 |

| Total Refugees and Protected Persons in-Canada | 20,121 | 2,418 | 1,498 | 19,251 | 2,470 | 45,758 |

| Female | 8,666 | 1,289 | 697 | 9,909 | 1,251 | 21,812 |

| Male | 11,455 | 1,129 | 801 | 9,342 | 1,219 | 23,946 |

| All other immigration – Principal applicants | 1,450 | 325 | 299 | 243 | 73 | 2,390 |

| Female | 743 | 172 | 125 | 159 | 33 | 1,232 |

| Male | 707 | 153 | 174 | 84 | 40 | 1,158 |

| All other immigration – Partners and dependants | 913 | 150 | 119 | 107 | 67 | 1,356 |

| Female | 519 | 100 | 57 | 74 | 46 | 796 |

| Male | 394 | 50 | 62 | 33 | 21 | 560 |

| Total All Other Immigration | 2,363 | 475 | 418 | 350 | 140 | 3,746 |

| Female | 1,262 | 272 | 182 | 233 | 79 | 2,028 |