Public Health Agency of Canada 2017–18 Departmental Results Report

Download the entire report

(PDF format, 1.12 MB, 53 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: 2018-11-20

ISSN: 2561-1410

Table of Contents

- Minister’s message

- Results at a glance

- Raison d’être, mandate and role: who we are and what we do

- Operating context and key risks

- Results: what we achieved

- Analysis of trends in spending and human resources

- Supplementary information

- Appendix: definitions

- Endnotes

Minister’s message

I am pleased to present the Public Health Agency of Canada's (PHAC) 2017–18 Departmental Results Report. This report provides an overview of the progress and results PHAC has achieved in promoting and protecting the health and safety of Canadians.

Throughout the past year, PHAC provided strong leadership and collaborated closely with key partners to address a range of complex public health issues most important to Canadians.

The Agency continued its focus on disease and injury prevention, and strengthened efforts to increase vaccination uptake across Canada. This included the launch of a new program to identify populations in Canada who are unvaccinated or under-vaccinated as well as the launch of a childhood vaccination public awareness campaign.

This year, PHAC also released the Canadian Guideline on Concussion in Sport, which will help raise awareness about this important issue.

As part of the Government of Canada's comprehensive response to the opioid crisis, the Agency worked closely with provincial and territorial partners and stakeholders to ensure Canadians had access to critical data to support the identification and prevention of problematic opioid use and overdose.

The Agency focused on promoting good physical and mental health by making important investments to support suicide prevention, promote positive mental health and address family and gender-based violence. PHAC also released the National Autism Spectrum Disorder Surveillance System Report, which provides, for the first time ever, a comprehensive review of autism patterns among our children and youth.

Finally, PHAC continued to demonstrate scientific excellence and leadership in response to public health threats. Several initiatives were developed to strengthen Canada's ability to combat the risks of antimicrobial resistance, reduce tuberculosis among vulnerable populations, and address sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections in Canada.

These achievements would not have been possible without the collective efforts of our partners, and I look forward to continued collaboration with provincial and territorial governments and all sectors to improve the overall health of Canadians.

The Honourable Ginette Petitpas Taylor, P.C., M.P.

Minister of Health

Results at a glance

Actual spending

$607,102,554

Actual full-time equivalents

2,075

Results highlights

- In support of the response to the opioid crisis and in an effort to deliver timely and relevant information, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) provided critical surveillance data for Canadians on the new opioids website.

- To increase vaccination uptake across Canada, national vaccination coverage goals were updated and a new research program was established to identify populations in Canada who are unvaccinated or under-vaccinated, with a special emphasis on vulnerable populations and Indigenous peoples.

- To raise awareness among athletes, parents and coaches across the country, PHAC developed concussion awareness, education and management tools and resources, including the release of the Canadian Guideline on Concussion in Sport.

- To address significant needs in the areas of mental health promotion and mental illness prevention, PHAC strengthened surveillance of mental illnesses, published new data on the positive mental health of youth, available on Public Health Infobase, and supported Crisis Services Canada on the delivery of the Canada Suicide Prevention Service.

- To address antimicrobial resistance (AMR) from a One Health approach,Footnote 1 PHAC strengthened national capacity to combat the risk of AMR through, for example, the release of the Pan-Canadian Framework on AMR, the release of the 2017 Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System Report, and the ongoing development of a Pan-Canadian Action Plan.

- To address health inequalities in remote and vulnerable populations such as Indigenous communities, PHAC improved national laboratory capacity to meet changing infectious disease research and testing needs by, for example, providing laboratory support.

For more information on PHAC’s plans, priorities and results achieved, see the “Results: what we achieved” section of this report.

Raison d’être, mandate and role: who we are and what we do

Raison d’être

Public health involves the organized efforts of society that aim to keep people healthy and to prevent illness, injury and premature death. The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) has put in place programs, services and policies to help protect and promote the health of all Canadians and residents of Canada. In Canada, public health is a responsibility that is shared by all three levels of government in collaboration with the private sector, non-governmental organizations, health professionals and the public.

In September 2004, PHAC was created within the federal Health Portfolio to deliver on the Government of Canada’s commitment to increase its focus on public health in order to help protect and improve the health and safety of all Canadians and to contribute to strengthening public health capacities across Canada.

Mandate and role

PHAC has the responsibility to:

- Contribute to the prevention of disease and injury, and to the promotion of health;

- Enhance surveillance information and expand the knowledge of disease and injury across Canada;

- Provide federal leadership and accountability in managing responses to national public health events;

- Strengthen intergovernmental collaboration on public health and facilitate national approaches to public health policy and planning; and

- Serve as a central point for sharing public health expertise across Canada and with international partners, and to use this knowledge to inform and support Canada’s public health priorities.

For more general information about the department, see the “Supplementary information” section of this report. For more information on the department’s organizational mandate letter commitments, see the Minister’s mandate letter.

Operating context and key risks

Operating context

PHAC operates in a complex, interconnected, and evolving environment where drivers such as social determinants of health, climate change, and advancements in technology impact Canadians. For instance, global supply chains and rapid international transportation systems move goods and people across national borders, carrying with them the risk that a health threat emerging from somewhere in the world, could enter Canada. Similarly, climate change presents a range of risks, from the spread of specific diseases to extreme weather events.

Although Canada is one of the healthiest countries in the world, health inequalities persist. While the life expectancy of Canadians is higher than ever, not all experience the same health status. Vulnerable populations (such as low-income families, children, Indigenous peoples, and the elderly) face heightened risks of poor health outcomes, including chronic and infectious disease, injury, mental illness, and obesity.

Canada will continue to face some persistent public health challenges in the coming years, for example:

- Rising rates of chronic diseases (the cause of 65% of all deaths in Canada each year);

- The emerging and re-emerging infectious disease, including those related to climate change, vaccine-preventable diseases, and AMR;

- Rising obesity rates;

- Increasing mental health and problematic substance use;

- An aging population; and

- The spread of drug resistant organisms will influence the ability of PHAC’s programs to deliver and achieve results for Canadians.

Unforeseen public health events mean that PHAC must continue to have the capacity to rapidly and effectively respond. To do so, credible and timely data is required to support evidence-based decision making. Technology (e.g., whole genome sequencing and genetic fingerprinting) provides PHAC, and its partners and stakeholders, with a wide range of resources to address public health issues. As technology continues to advance, its role in public health will also change. The wide range of available technologies will continue to be used in educating, informing, training, and communicating with both individuals and public health professionals; detecting infectious disease outbreaks through surveillance and data collection; monitoring of chronic disease and injuries; improving the speed and accuracy of diagnoses; and providing new and more effective treatments.

Public health is a shared responsibility. By improving its understanding of the priorities, activities, and concerns of partners and stakeholders, PHAC will be better able to adapt its programs to respect the diversity across Canada. PHAC’s commitment to accountability, openness, and results will help foster these important multi-sectoral collaborations and the solutions needed to help improve the health of Canadians.

Key risks

PHAC manages a range of risks in pursuing its mission to promote and protect the health of Canadians and in consideration of its operating context. The risks identified in the following table are drawn from PHAC’s 2016–19 Corporate Risk Profile (CRP). These risks are ranked as having the greatest potential to significantly impact PHAC’s ability to achieve its objectives, and having the most important potential health and safety consequences for Canadians in the event of a failure of any risk response strategy.

Risk 1: Simultaneous Events/Large Event

Risk Statement:

There is a risk that a significant or simultaneous public health event(s) may occur and PHAC may not have the scope and depth of workforce or the capacity and resources required to mobilize an effective and timely response, while maintaining its non-emergency obligations. This may hinder PHAC’s role in providing leadership in the coordination and integration of the Health Portfolio’s emergency preparedness and response functions, and implementation of other public health priorities.

Risk Drivers:

- Ability to mobilize resources to support other stakeholders (e.g., provinces, territories, and international organizations);

- Availability of science and technical expertise to respond to public health events;

- Mobilizing PHAC capacity to respond to events, sustain existing priorities, and promote workplace wellness;

- Frequency, scope, and/or globalization of public health events; and

- Capacity of public health partners to address public health emergencies.

Risk Response Strategies:

Update the Health Portfolio All-Hazards Risk and Capability Assessment to better understand public health capacity gaps and support prioritization of opportunities for enhanced preparedness.

Progress Against Risk Response Strategy

- Hosted a Health Portfolio All-Hazard Risk and Capability Assessment workshop with participants from across the Health Portfolio, regions, and observers from other government departments. This workshop contributed to the assessment of several priority threats/hazards.

Increase PHAC’s ability to rapidly mobilize personnel to respond to public health events/emergencies.

Progress Against Risk Response Strategy

- Launched the All Event Response Operations application, a web-based database that facilitates the rapid identification of employees across the Health Portfolio with the necessary skills and experience to respond to public health events and emergencies.

Leverage new technologies to foster greater information sharing and communication between stakeholders (e.g., online portals and the Canada Communicable Disease Report (CCDR) online).

Progress Against Risk Response Strategy

- Developed a rapid communication capacity to quickly release infectious disease information to frontline public health professionals e.g., notification of the first reported case of a new multidrug-resistant fungal infection in Canada; and new recommendations to address an ongoing outbreak.

- Hosted webinars to present surveillance findings to stakeholders.

- Produced the Canadian Guidelines on Sexually Transmitted Infections for health care providers across Canada and fostered greater information sharing through a mobile app that sends notifications to users about updates to chapters in the Guidelines.

- Posted alerts and notifications about new publications and tools through the Canadian Network for Public Health Intelligence and PHAC's Expert Working Group on Sexually Transmitted Infections.

Link to the department’s Programs:

- 1.1: Public Health Infrastructure

- 1.3: Health Security

Link to mandate letter commitments or to government-wide and departmental priorities:

- PHAC Priority 1: Strengthened public health capacity and science leadership

- PHAC Priority 3: Enhanced public health security

Risk 2: Access to Timely and Accurate Data

Risk Statement:

There is a risk that, as the volume of and need for public health data increases both domestically and internationally, PHAC may not have access to timely, reliable and accurate information and/or data, nor the ability to undertake necessary data analysis, which could reduce effective evidence-based decision-making pertaining to public health matters.

Risk Drivers:

- Information security;

- Information sharing legislation;

- Consistency and availability of Federal/Provincial/Territorial (F/P/T) data;

- Data to support effective performance measurement and monitoring;

- Aging infrastructure, including Information Technology, mission-critical applications and procurement mechanisms; and

- Access to timely information (e.g., Vital Statistics; and data from the Canadian Institute for Health Information and Statistics Canada).

Risk Response Strategies:

Work with provincial and territorial (P/T) stakeholders to support timely information sharing and continued technology implementation (e.g., PulseNet Canada, the Canadian Public Health Lab network, and Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System, and the Electronic Canadian Hospital Injuries Reporting and Prevention Program).

Progress Against Risk Response Strategy

- Provided timely and accurate surveillance data by posting the following reports online:

- FluWatch (weekly; monthly in summer);

- Measles and rubella surveillance (weekly);

- Respiratory Virus Detection Surveillance System (weekly);

- Vaccine Safety [annually in the Canada Communicable Disease Report (CCDR)]; and

- Vaccine Preventable Disease Surveillance (every 2 years).

- Collaborated on the planning of a pilot project with P/T stakeholders that will present selected health care acquired infections' surveillance data on the Canadian Institute for Health Information’s user-friendly website.

- Worked with P/T stakeholders in exploring new data sources, including the assessment of expanding the Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program to include a self-inflicted injury form, which helps address an important gap in intentional injury data.

- Launched Data Tools as part of the Public Health Infobase platform to help users visualize public health data from the Chronic Disease Surveillance System with geographic comparisons, trends, age distributions, and other perspectives.

Collaborate with P/Ts to implement the Action Plan of the Blueprint for a Federated System for Public Health Surveillance in Canada with a focus on strengthening the infrastructure that supports public health surveillance.

Progress Against Risk Response Strategy

- Collaborated with P/Ts to begin the implementation of the Action Plan. This effort included developing a Pan-Canadian Public Health Surveillance Ethics Framework which identifies common ethical values and principles regarding the use and dissemination of shared data and public health information.

Conduct assessments to improve the way PHAC uses, disseminates, and shares information in terms of the availability, usability, and uptake of PHAC reports and publications (e.g., CCDR, Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada journal, surveillance reports, and guidance materials).

Progress Against Risk Response Strategy

- Collected information from P/Ts and key stakeholders as part of a process to develop infection prevention and control guidelines to:

- Identify information needs; and

- Explore ways to improve uptake of recommendations to improve the health of Canadians.

- Improved the international reach of The Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada Journal to full science content through new membership and indexing in the Directory of Open Access Journals - a platform for open access scholarly journals. PHAC continues to monitor the number of users of its information disseminated via all available platforms (i.e., Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn, and Canada.ca).

- Collaborated with F/P/T partners to provide Canadians with information about the state of community water fluoridation within their province/territory, as well as nationally, by publishing the national report, “The State of Community Water Fluoridation across Canada 2017” and a map, Community Water Fluoridation in Canada, 2017.

Link to the department’s Programs:

- 1.1: Public Health Infrastructure

- 1.2: Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

Link to mandate letter commitments or to government-wide and departmental priorities:

- PHAC Priority 1: Strengthened public health capacity and science leadership

- PHAC Priority 4: Excellence and innovation in management

Risk 3: Keeping up with the Changing External Environment

Risk Statement:

There is a risk that PHAC may not be able to keep up with the rapid pace of change in the external environment. This may include advancements in communications, scientific discoveries and emerging public health technologies. This may hinder PHAC’s ability to maintain its relevance, which could affect its ability to exhibit excellence and innovation in public health.

Risk Drivers:

- Modernization of legislation, regulations and policies;

- Reputation and relationships with stakeholders and Canadians;

- Public communication and trust (social media, public interaction, etc.);

- Availability and access to public information on websites and social media;

- Public health awareness and knowledge transfer;

- International or domestic adoption of new technologies; and

- Keeping pace with new discoveries.

Risk Response Strategies:

Translate research and evidence into information and tools that promote good health and prevent disease and injury.

Progress Against Risk Response Strategy

- Collaborated with P/Ts and external experts in the field of infection prevention and control on an ongoing basis to address public health events, and develop guidance to prevent the spread of infections in healthcare settings (e.g., “Pre-hospital Care and Ground Transport of Patients with Suspected or Confirmed Ebola Virus Disease”).

- Improved data sources and methods to more accurately measure progress against the global Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) targets.

- Expanded accessibility of information through, for example, adding more visualization tools and data extracts to Notifiable Diseases On-Line to enable stakeholders to conduct their own analyses and prepare their own information products as needed.

Target the development and/or enhancement of innovative science and emerging laboratory technology and practices (e.g., genomics).

Progress Against Risk Response Strategy

- Increased the use of genome sequencing technology to determine the sources of food that resulted in illnesses and outbreaks. For example, PulseNet Canada was able to use genomic analysis to identify flour as the food source responsible for a nation-wide E.coli outbreak in 2017-18.

Link to the department’s Programs:

- 1.1: Public Health Infrastructure

- 1.2: Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

- 1.3: Health Security

Link to mandate letter commitments or to government-wide and departmental priorities:

- PHAC Priority 1: Strengthened public health capacity and science leadership

- PHAC Priority 2: Leadership on health promotion and disease prevention

- PHAC Priority 3: Enhanced public health security

- PHAC Priority 4: Excellence and innovation in management

Risk 4: Public Health Agency Physical Infrastructure

Risk Statement:

There is a risk that without necessary and adequate infrastructure, as well as timely maintenance of, and investment in, facilities and assets, PHAC may be exposed to threats which could impact how PHAC will deliver on its mandate and objectives.

Risk Drivers:

- Adopting and integrating technologies;

- Physical security; and

- Laboratory space.

Risk Response Strategies:

Assess existing laboratory capacity as part of developing a strategy to make the best use of Canada’s biocontainment laboratory facilities.

Progress Against Risk Response Strategy

- Made progress in converting existing laboratory space to the highest level of biosafety (Containment Level 4) which enhances national laboratory capacity to respond to global and domestic public health threats.

Link to the department’s Programs:

- 1.1: Public Health Infrastructure

Link to mandate letter commitments or to government-wide and departmental priorities:

- PHAC Priority 1: Strengthened public health capacity and science leadership

- PHAC Priority 4: Excellence and innovation in management

Results: what we achieved

Programs

Program 1.1: Public Health Infrastructure

Description

The Public Health Infrastructure Program strengthens Canada’s public health, workforce capability, information exchange, and federal, provincial and territorial networks, and scientific capacity. These infrastructure elements are necessary for effective public health practice and decision-making in Canada. The program works with federal, provincial and territorial stakeholders in planning for and building strategic and targeted investments in public health infrastructure, including public health research, training, tools, best practices, standards, and mechanisms to facilitate information exchange and coordinated action. Public health laboratories provide leadership in research, technical innovation, reference laboratory services, surveillance, outbreak response capacity and national laboratory coordination to inform public health policy and practice. Through these capacity-building mechanisms and scientific expertise, the Government of Canada facilitates effective coordination and timely public health interventions which are essential to having an integrated and evidence-based national public health system based on excellence in science. Key stakeholders include local, regional, provincial, national and international, public health organizations, practitioners and policy makers, researchers and academics, professional associations and non-governmental organizations.

Results

During 2017–18, PHAC made progress in supporting an effective Canadian public health system with results and highlights as noted below.

Scientific and Laboratory Capacity

PHAC improved national laboratory capacity to meet Canada’s needs for infectious disease testing and research by:

- Deploying a team to deliver on site lab testing capacity to the Qikiqtarjuaq, a remote community, during a tuberculosis outbreak;

- Increasing the use of whole genome sequencing technology in food-borne illness outbreaks. For example, PHAC’s innovative approaches to laboratory testing and analysis supported the Canadian Food Inspection Agency’s (CFIA) actions to require industry to implement measures to eliminate Salmonella in frozen raw breaded chicken products by April 2019. A 2018 Evaluation of the Agency’s Foodborne Illness Activities details additional achievements and challenges related to genome sequencing; and

- Increasing the availability of biosafety Containment Level 4 – the highest level of biosafety – laboratory space at the National Microbiology Laboratory to handle the most dangerous pathogens.

Public Health Surveillance, Information, and Networks

- PHAC continued to support on-going implementation of the Multi-Lateral Information Sharing Agreement, which sets out why, how, what and when F/P/T governments share and use information on infectious diseases and public health events.

- PHAC collaborated with P/Ts to begin implementation of the Blueprint for a Federated System for Public Health Surveillance in Canada. This effort included developing a Pan-Canadian Public Health Surveillance Ethics Framework, which identifies common ethical values and principles regarding the use of shared public health information.

Public Health Capacity

- In preparation for Canada’s 2018 Joint External Evaluation, PHAC led a comprehensive self-assessment of Canada’s capacity to prevent, detect and rapidly respond to public health threats occurring either naturally, or due to deliberate or accidental events.

| Expected results | Performance indicators | Target | Date to achieve targetFootnote a | Actual results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017–18 | 2016–17 | 2015–16 | ||||

| Canada has the public health system infrastructure to manage public health risks of domestic and international concern | Level of Canada’s compliance with the public health capacity requirements outlined in the International Health Regulations | 2 | March 31, 2017 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Public health professionals have timely access to peer reviewed laboratory and surveillance publications to inform public health action | Number of citations referencing Agency laboratory research publications | 1,800 | March 31, 2017 | 4,343Footnote b | 2,974 | 2,850 |

| Percent of accredited reference laboratory tests conducted within the specified turnaround times | 95 | March 31, 2017 | 94.6Footnote c | 95.8 | 96.6 | |

| 2017–18 Main Estimates |

2017–18 Planned spending |

2017–18 Total authorities available for use |

2017–18 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2017–18 Difference (Actual spending minus Planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 110,828,058 | 110,828,058 | 117,231,815 | 116,974,098 | 6,146,040 |

| 2017–18 Planned full-time equivalents |

2017–18 Actual full-time equivalents |

2017–18 Difference (Actual full-time equivalents minus Planned full-time equivalents) |

|---|---|---|

| 735 | 698 | (37) |

Actual FTEs were less than planned primarily due to a realignment of resources.

Program 1.2: Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

Description

The Health Promotion and Disease Prevention Program aims to improve the overall health of the population—with additional focus on those that are most vulnerable—by promoting healthy development among children, adults and seniors, reducing health inequalities, and preventing and mitigating the impact of chronic disease and injury, as well as infectious diseases. Working in collaboration with provinces, territories, and stakeholders, the Program develops and implements federal aspects of frameworks and strategies (e.g., Curbing Childhood Obesity: A Federal, Provincial and Territorial Framework for Action to Promote Healthy Weights, national approaches to addressing immunization) geared toward promoting health and preventing disease. The Program carries out primary public health functions of health promotion, surveillance, science and research on diseases and associated risk and protective factors to inform evidenced based frameworks, strategies, and interventions.

Results

During 2017–18, PHAC made progress in addressing critical health promotion and disease prevention challenges as noted below.

Immunization

Immunization is one of the most effective public health strategies for protecting populations against infectious disease threats. Consequently, PHAC collaborates with P/T governments, academia, and professional associations to maximize the impact of immunization programs. For example, in 2017–18:

- PHAC updated national vaccination coverage goals that specify targets to protect Canadians from vaccine-preventable diseases;

- A new research program is in place to reach the unvaccinated or under-vaccinated, with an emphasis on hard-to-reach populations and Indigenous peoples;

- In response to a recommendation outlined in the 2016 Evaluation of Immunization and Respiratory Infectious Disease Activities, enhancements were made to the National Childhood Immunization Coverage Survey to improve estimates of vaccination coverage and measure vaccine hesitancy; and

- PHAC’s Immunization Partnership Fund, launched in 2016, invested in 5 new projects in 2017–18; notable among these is Kids Boost Immunity, an online learning platform to improve student literacy about vaccination using games.

Sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBI)

Prevention, detection, and treatment of STBBI are domestic and global priorities, and Canada is part of global efforts to eliminate these infections by 2030. In 2017–18, the following progress was made:

- To reduce the health impact of STBBI and to contribute to global efforts, a Pan-Canadian Framework for Action on STBBI was drafted in consultation with people living with HIV and Hepatitis C, representatives of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, and 2-Spirited (LGBTQ2) communities, and P/T governments;

- Community-based projects were funded under the Hepatitis C and HIV Community Action Fund to support prevention, detection, and access to treatment;

- Surveillance programs were enhanced to monitor progress in achieving the global HIV treatment targets known as “90-90-90”; and

- PHAC's National Microbiology Laboratory deployed "point of care" HIV testing into rural and remote communities to improve diagnostic capabilities in these communities.

Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR)

The growing resistance of microbes to antibiotic drugs is a global public health threat. PHAC is coordinating multi-sectoral efforts under a “One Health” approach to combat this challenge. In 2017–18, the following progress was made:

- The Pan-Canadian Framework for Action on AMR was developed in collaboration with P/T governments and stakeholders involved in addressing AMR, and released by the federal Ministers of Health and Agriculture;

- Working with multiple sectors, Canada's response to AMR continued with the drafting of a Pan-Canadian Action Plan on AMR;

- PHAC published its 2017 Canadian AMR Surveillance System Report and initiated work to fill data gaps in community surveillance and long-term care; and

- PHAC initiated a project with the Council of Canadian Academies to better understand the socio-economic implications of AMR to inform a more comprehensive response.

Foodborne Illness

PHAC provides epidemiological and laboratory analyses to support investigations of outbreaks and trend analyses aimed at improving food safety. In 2017–18:

- PHAC coordinated 15 outbreak investigations in collaboration with the CFIA and Health Canada (HC), provided technical support for 4 single jurisdictions, and communicated with Canadians about the investigations and other relevant food safety information through the Public Health Notices and social media; and

- PulseNet Canada confirmed flour as the food source responsible for a nation-wide E.coli outbreak in 2017–18 using whole genome sequencing technology.

Vector-borne Illness

Climate change is likely to drive an increase in infectious diseases transmitted by, for example, mosquitoes and ticks in Canada. PHAC plays a public health role in prevention and detection, and coordinates national responses to inform Canadians about risks and protective measures. 2017–18 highlights include:

- The Federal Framework on Lyme Disease and the complementary Federal Action Plan were released pursuant to the Federal Framework on Lyme Disease Act;

- PHAC led a public awareness campaign to provide Canadians with timely, user-friendly information to prevent tick bites;

- Using national surveillance data, PHAC provided information to Canadians on the risks, and raised awareness about protection, when travelling to Zika-affected countries; and

- PHAC launched a new funding program – the Infectious Diseases and Climate Change Fund – to improve surveillance and public awareness of infectious diseases affected by climate change.

Tuberculosis (TB)

To reduce rates of TB in areas of high incidence:

- PHAC coordinates the Canadian Tuberculosis Surveillance System (CTSS). A special edition of the Canada Communicable Disease Report was published with CTSS data resulting in a better understanding of the scope of this public health challenge in Canada;

- A pilot implementation plan was developed aimed at reducing the burden of TB in Indigenous communities where TB is prevalent; and

- A project was supported to evaluate the uptake and completion of a shorter course of treatment for latent TB infection in foreign-born Canadians.

Healthy Living and Injury Prevention

PHAC worked with partners to design and deliver innovative solutions to encourage Canadians to make healthy living choices and reduce their risk of injury. PHAC also expanded Canadians’ knowledge and understanding of the reasons and ways they can protect themselves against chronic diseases and injuries. For example:

- In response to the national opioid crisis, and the Ministerial commitment to ensure that Canada has a consistent and timely surveillance system for monitoring and reporting on opioid overdoses and related deaths, PHAC played a leadership role at the federal level by leading a new task group with P/Ts to develop quarterly national surveillance reports on apparent opioid-related deaths;

- PHAC raised awareness among athletes, parents, and coaches across the country about concussion prevention, early identification, and management by developing:

- The Canadian Guideline on Concussion in Sport to provide a more consistent approach to concussion management, which addressed an opportunity identified in the 2014 evaluation of the Active and Safe Injury Prevention Initiative;

- The SCHOOLFirst handbook for child and youth educators to support students’ return to school following a concussion, and a mobile app for parents and schools on concussion awareness and recovery; and

- An accredited online concussion training course for medical and allied health professionals.

- To increase the understanding of Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) in Canada, PHAC released the National Autism Spectrum Disorder Surveillance System 2018 Report, which provides, for the first time, a comprehensive review of the patterns in Autism in children and youth in Canada. For example, in 2015, males were diagnosed with ASD four times more frequently than females;

- In support of physicians and other health care workers delivering preventive health care, PHAC worked closely with the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care to produce evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. In 2017–18, guidelines were issued for adults (hepatitis C and abdominal aortic aneurysm), and school aged children and youth (prevention and treatment of cigarette smoking);

- To increase the understanding of physical activity, sedentary behaviour, and sleep, PHAC and its partners published results in the Health Reports and in the Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada journal outlining the extent to which the Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Children and Youth are being met. Overall, boys exceeded girls in the time engaged in physical activity as well as screen time.

Mental Health Promotion and Suicide Prevention

During 2017–18, PHAC made progress in addressing significant needs across Canada in the areas of mental health promotion and mental illness prevention. For example, in 2017–18, PHAC:

- Funded four community-based programs to improve mental health and well-being under the Innovation Strategy. These programs reached 53,525 Canadians and leveraged over $1.2 million in additional funding resulting in a positive impact on the emotional, psychological, and social-wellbeing of vulnerable children, youth, and their families,Footnote 2 as outlined in the evaluation of Mental Health and Mental Illness activities for Health Canada and PHAC;

- Invested $6.25 million in community-based programs aimed at meeting the needs of survivors of family violence through parenting support, physical activity, arts- and culture-based programs, etc. As a result, these programs helped strengthen parenting skills, mental health coping strategies, and social and emotional skills so that children and their families can rebuild their lives and health;

- Supported Indigenous partners in their efforts to promote mental health through the implementation of the First Nations Mental Wellness Continuum Framework, which represents a shared vision to promote well-being through partnerships among First Nations individuals, families and communities across Canada;

- Provided support to Crisis Services Canada in the delivery of the Canada Suicide Prevention Service which provides free and confidential 24/7 support to individuals in crisis regardless of where they live in Canada. From the launch of the service in November 2017 to March 2018, support was provided to 8,496 people in need across Canada, including 91 life-threatening rescues.

Seniors and Aging

Seniors represent the fastest growing age group in Canada, with projections estimating that nearly one in four (23%) will be 65 years of age or older by 2031. PHAC’s work over the past year has centered on supporting healthy aging and those affected by dementia. For example, in 2017–18 PHAC:

- Raised awareness about dementia by publishing Canada’s first national surveillance data on dementia, from the Canadian Chronic Disease Surveillance System, through a fact sheet, infographic, Public Health Infobase, and Canadian Chronic Disease Indicators, demonstrating the higher prevalence of dementia among women, and how aging increases this gap between men and women.

- Continued to support innovative solutions to promote brain health through an investment of $42 million (2015–16 to 2019–20) to Baycrest Health Science for the Center for Aging and Brain Health Innovation; and

- In support of improving the well-being of Canadians living with dementia, worked with key stakeholders to begin implementing the National Strategy for Alzheimer’s Disease and other Dementias Act. These efforts included planning for a National Dementia Conference, and working to establish a Ministerial Advisory Board on Dementia, all of which will inform a national dementia strategy.

Vulnerable Children and Families

Supporting the healthy development of vulnerable children is consistent with Canada’s commitments to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Early development, from pregnancy through childhood, represents a critical stage of the life course and the best opportunity to positively influence the mental and physical health trajectory of an individual. In 2017–18, PHAC:

- Helped address improvements for the safety and quality of the Aboriginal Head Start in Urban and Northern Communities learning environment through a one-year, $15.4 million investment to upgrade key infrastructure such as buildings, vehicles, etc.; and

- Promoted early childhood development by launching online resources on the health, social, economic, and other factors relevant to children and families, including a component on Indigenous children and families. This was accomplished through the Canadian Council on Social Determinants of Health, a collaborative group of leaders from the public and private sectors working with the Canadian Institute of Child Health.

Innovation and Experimentation

Innovation and experimentation are central to PHAC’s federal public health role in domestic and global leadership. Some achievements include:

- An innovative approach to test for blood borne infections through point of care testing and the collection of dried blood spot samples was delivered in First Nations communities to improve access to testing and decrease stigma;

- eTick.ca, a PHAC collaborative pilot project with Bishop’s University and the Laboratoire de santé publique du Québec, was launched to involve the public in monitoring tick populations;

- Upgrades to the CANImmunize mobile app were launched to allow Canadians to store their vaccination records on their mobile phones and make them available on all their devices;

- In collaboration with Capsana, the Activate Your Health workplace program was launched to motivate and support employees, especially women aged 25 to 54 years, to improve their lifestyle choices in eating habits, physical activity, and the reduction of sedentary behaviour;

- PHAC supported the collaborative Kid Food Nation project with the Boys and Girls Club of Canada, Corus Entertainment, Dietitians of Canada, and President's Choice Children's Charity in order to engage young Canadians, aged 7 to 12 and their families, to improve their food knowledge and food skills to support healthier eating;

- In 2017–18, PHAC’s Innovation Strategy program funded 11 research projects across the country to promote mental health and healthier weights. These innovative projects helped create supportive environments for Canadians to develop healthy habits and address the common risk factors underlying many chronic diseases. In the most recent reporting year,Footnote 3 66% of projects reported improvements in positive behaviours and healthier outcomes for individuals, families, and communities. In addition, these projects developed 891 partnerships and leveraged over $4.4 million in additional funding leading to over 100 concrete changes in policy, practice, or programming related to mental health and healthy eating across the country; and

- PHAC launched a Health Inequalities Data Tool that allows users to explore, visualize, and download data on more than 70 indicators that affect health. This tool allows Canadians to see differences in health status based on factors such as sex, health behaviours, working conditions, access to healthcare, and physical and social environments.

| Expected result | Performance indicators | Target | Date to achieve targetFootnote a | Actual results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017–18 | 2016–17 | 2015–16 | ||||

| Diseases in Canada are prevented and mitigated | Rates per 100,000 of key infectious diseases | HIV: 6.41 | March 31, 2017 | 6.4 | 5.8 | 5.8 |

| Hepatitis B: 15.1 | 13.7 | 13.2 | 15.2 | |||

| Hepatitis C: 29.5 | 31.1Footnote b | 30.4 | 29.7 | |||

| Tuberculosis: 3.6 | 4.8Footnote b | 4.6 | 4.4 | |||

| E-Coli 0157: 1.39 | 0.95 | 1.14 | 1.05 | |||

| Salmonella: 19.68 | 19.92Footnote c | 21.45 | 21.85 | |||

| Invasive Pneumococcal Disease in adults, 60 years and older: 12.4 | Not applicable (N/A)Footnote d |

19.95 | 20.38 | |||

| Measles acquired in Canada (not related to travel): 0.7 | 0 | 0 | N/AFootnote e | |||

| Number of pertussis (whooping cough) deaths in children of less than or equal to three months of age | 0 | 1Footnote f | 0 | 0 | ||

| Percent of national immunization coverage goals met for children | 100 | N/AFootnote g | N/AFootnote h | N/AFootnote e | ||

| Percent of national immunization coverage goals met for adults | 100 | N/AFootnote h | 0Footnote i | N/AFootnote e | ||

| Rate of key chronic disease risk factors (percent of adults aged 20 and over that report being physically active) | 52Footnote j (by March 31, 2017) |

51.9 | 51.9 | 51.9 | ||

| Rate of key chronic disease risk factors (percent of children and youth aged 5 to 17 who are overweight or obese) | 32Footnote k (Ongoing) |

30.3 | 31.2 | 31.2 | ||

| 2017–18 Main Estimates |

2017–18 Planned spending |

2017–18 Total authorities available for use |

2017–18 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2017–18 Difference (Actual spending minus Planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 309,597,402 | 309,597,402 | 331,683,753 | 323,806,168 | 14,208,766 |

| 2017–18 Planned full-time equivalents |

2017–18 Actual full-time equivalents |

2017–18 Difference (Actual full-time equivalents minus Planned full-time equivalents) |

|---|---|---|

| 829 | 775 | (54) |

Actual FTEs were less than planned primarily due to a realignment of resources.

Program 1.3: Health Security

Description

The Health Security Program takes an all hazards approach to the health security of Canada’s population, which provides the Government of Canada with the ability to prevent, prepare for, and respond to public health events/emergencies. This program seeks to bolster the resiliency of the populations and communities, thereby enhancing the ability to cope and respond. To accomplish this, its main methods of intervention include actions taken through collaborations with key jurisdictions and international collaborators. These actions are carried out by fulfilling Canada’s obligations under the International Health Regulations and through the administration and enforcement of pertinent legislation and regulations.

Results

During 2017–18, PHAC made progress in strengthening health security with results and highlights as noted below.

Emergency Preparedness and Response

- To help Canada prepare for, and respond to, public health events and emergencies, PHAC regularly refines and tests its emergency management plans and procedures. In 2017–18, PHAC:

- Collaborated with federal and provincial partners to finalize the F/P/T Public Health Response Plan for Biological Events, which describes roles, responsibilities, and authorities of F/P/T governments for public health and emergency management; and

- Participated in three emergency preparedness and response exercises – Operation Nanook, Staunch Maple, and Sentinel – which provided PHAC the opportunity to practice and improve its capabilities related to preventing and/or responding to domestic and international public health emergencies and events.

- To better prepare Canada for biological, chemical, and radiological events and other emergencies, PHAC made targeted investments in medical countermeasures for the NESS. In addition, the NESS provided medical equipment and pharmaceuticals for emergency responses in British Columbia and Northwest Territories during the wildfires, in Newfoundland and Labrador and Nunavut during tuberculosis incident, in Quebec and Ontario for Asylum Seekers, and across Canada in response to the opioid crisis.

Border and Travel Health

- PHAC communicated travel health risks on travel.gc.ca in order for Canadians to protect themselves while travelling to affected countries or major events such as the 2018 Winter Olympics in South Korea.

- PHAC helped reduce public health risks associated with travel by:

- Helping regulated parties comply with the Food and Drugs Act and Potable Water on board Train, Vessels, Aircraft and Buses Regulations;

- Providing guidance and technical expertise to international, F/P/T, and local public health partners (e.g., sharing best practices with 17 Caribbean countries in the development and implementation of local Ship Sanitation Programs); and

- Publishing technical information (e.g., from the Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel) to help in the development of travel and tropical medicine guidelines for health care professionals.

Biosecurity

- PHAC continued to protect the health and safety of Canadians by enforcing the Human Pathogens and Toxins Act and Regulations, as well as certain provisions of the Health of Animals Regulations. During the year, PHAC processed 307 Pathogen and Toxin Licence applications within established service standards, and monitored activities to verify that licensees were complying with laws and regulations.

- As a designated World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborating Centre for Biosafety and Biosecurity, PHAC contributed to global public health priorities by:

- Providing technical expertise in support of WHO smallpox inspections;

- Sharing best practices related to inspections and assessing the risks of pathogens; and

- Actively contributing to the development of international biosafety standards as a member of the editorial board for the WHO Laboratory Biosafety Manual.

- To reduce the risk of exposure to pathogens or toxins in Canadian laboratories, PHAC implemented a national web-based surveillance system for reporting on laboratory incidents. Data collected through this system, and published in its 2016 report, is used to determine, for example, if biocontainment training and standards should be enhanced.

Regulatory Programs

- Key reports and documents were made available to stakeholders and the public on PHAC’s web site to:

- Support regulatory openness and transparency;

- Promote compliance with laws and regulations related to pathogens and toxins; and

- Demonstrate how regulated parties follow the rules to protect the health of Canadians.

- Examples include a surveillance report on Laboratory Exposures to Human Pathogens and Toxin: Canada 2016 and traveller health assessment statistics.

| Expected result | Performance indicators | Target | Date to achieve targetFootnote a | Actual results | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2017–18 | 2016–17 | 2015–16 | ||||

| Canadians are protected from threats to public health | Percent of collaborative relationships with key jurisdictions and international organizations in place to prepare for and respond to public health risks and events | 100 | March 31, 2017 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Percent of Government of Canada’s health emergency and regulatory programs implemented in accordance with the Emergency Management Act, the Quarantine Act, the Human Pathogens and Toxins Act and the Human Pathogens Importation RegulationsFootnote b | 100 | March 31, 2017 | 100 | 100 | 100 | |

| 2017–18 Main Estimates |

2017–18 Planned spending |

2017–18 Total authorities available for use |

2017–18 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2017–18 Difference (Actual spending minus Planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 61,360,077 | 61,360,077 | 67,620,506 | 69,155,991 | 7,795,914 |

Actual spending was higher than planned spending mainly due to a funding re-profile from 2018–19 to 2017–18 to Acquire Medical Countermeasures for Smallpox and Anthrax Preparedness, and funding for the G7 Summit in 2018.

| 2017–18 Planned full-time equivalents |

2017–18 Actual full-time equivalents |

2017–18 Difference (Actual full-time equivalents minus Planned full-time equivalents) |

|---|---|---|

| 312 | 306 | (6) |

Information on PHAC’s lower-level programs is available in the GC InfoBase.

Internal Services

Description

Internal Services are those groups of related activities and resources that the federal government considers to be services in support of programs and/or required to meet corporate obligations of an organization. Internal Services refers to the activities and resources of the 10 distinct service categories that support Program delivery in the organization, regardless of the Internal Services delivery model in a department. The 10 service categories are: Management and Oversight Services; Communications Services; Legal Services; Human Resources Management Services; Financial Management Services; Information Management Services; Information Technology Services; Real Property Services; Materiel Services; and Acquisition Services.

Results

Workplace Well-Being

- PHAC continued the implementation of the Multi-Year Diversity and Employment Equity Plan by recruiting, developing, and retaining a diverse workforce, and building an inclusive, respectful, and healthy workplace. As a result, PHAC continues to meet or exceed targets for representation of Women, Persons with Disabilities, Aboriginal Peoples, and Visible Minorities with respect to labour market availability.

- PHAC’s work in support of the Multi-Year Strategy for Mental Health and Wellness in the Workplace included a number of initiatives such as the continued implementation of National Standard for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace action plans.

- The continued delivery of Mental Health training sessions including mandatory workplace wellness training courses such as the Mental Health First Aid and the Building Blocks of Respect in the Workplace training sessions.Footnote 4

High-Performance Culture

- PHAC continued to support a culture of high performance through initiatives such as the Performance Management Initiative (PMI) and the Post-Secondary Recruitment program. The PMI completion rate for PHAC year-end assessments was 91.6%, well above the core public service average. PHAC also hired 40 new, indeterminate entry-level recruits exceeding last year’s hires, and offered 360 student placements through the Federal Student Work Experience Program, the Research Affiliate Program and CO-OP.

Communications

- PHAC took an enhanced digital-first approach to ensure that Canadians received timely and relevant information through social media on issues related to opioids, AMR, Lyme disease, seasonal flu, vaccinations, and a variety of food safety issues.

- PHAC used various social media channels to engage Canadians on priority public health issues. For example, through the Chief Public Health Officer’s twitter channel, PHAC helped raise the profile of the CPHO’s annual report on the State of Public Health in Canada, placed a spotlight on inspiring women in science at the Agency, and increased awareness on the opioid crisis and the stigma associated with substance use.

- PHAC also contributed surveillance data to support the launch of the Health Portfolio’s new opioids landing page to increase the availability and accessibility of important information related to the opioid crisis.

- PHAC strengthened the integration of communications and program functions, which helped improve the sharing of health and safety information with Canadians. For example, PHAC provided timely health and safety information to Canadians during various food outbreaks, including illnesses linked to flour, breaded chicken, romaine lettuce, and oysters.

- In support of innovative employee engagement and change management initiatives, PHAC organized a live webcast titled “Health Talks on Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples”. As well, a new web storytelling series called “PHAC: Working for Canadians” was launched featuring videos, articles, and other information describing how PHAC is tackling serious public health issues to keep Canadians safe and healthy.

Innovation and Experimentation

- i.HUB is an innovative support service and centre of expertise that is helping PHAC employees to improve program delivery. As an example, work is underway to determine how PHAC could re-design surveillance systems to address new and evolving challenges.

| 2017–18 Main Estimates |

2017–18 Planned spending |

2017–18 Total authorities available for use |

2017–18 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2017–18 Difference (Actual spending minus Planned spending) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90,149,394 | 90,149,394 | 110,250,932 | 97,166,297 | 7,016,903 |

| 2017–18 Planned full-time equivalents |

2017–18 Actual full-time equivalents |

2017–18 Difference (Actual full-time equivalents minus Planned full-time equivalents) |

|---|---|---|

| 597 | 296 | (301) |

The variance in FTE utilization is mainly due to the annual transfer of resources from PHAC to HC under the Health Portfolio Shared Services Partnership Agreement.

Analysis of trends in spending and human resources

Actual expenditures

Departmental spending trend graphFootnote 5

Text Description

| 2015–16 | 2016–17 | 2017–18 | 2018–19 | 2019–20 | 2020–21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sunset Programs – Anticipated | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Statutory | 41,090 | 38,139 | 39,885 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Voted | 531,991 | 521,078 | 567,218 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 573,081 | 559,217 | 607,103 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

The changes in spending from 2016–17 to 2017–18 are primarily due to funding for Early Learning and Child Care Infrastructure and Programming; Adapting to the Impacts of Climate Change; Strengthening the Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy; Government advertising programs (horizontal item); and re-profiling of funding to Acquire Medical Countermeasures for Smallpox and Anthrax Preparedness.

| Programs and Internal Services | 2017–18 Main Estimates |

2017–18 Planned spending |

2018–19 Planned spendingFootnote b |

2019–20 Planned spendingFootnote b |

2017–18 Total authorities available for use |

2017–18 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2016–17 Actual spending (authorities used) |

2015–16 Actual spending (authorities used) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Public Health Infrastructure | 110,828,058 | 110,828,058 | N/A | N/A | 117,231,815 | 116,974,098 | 111,593,778 | 116,628,229 |

| 1.2 Health Promotion and Disease Prevention | 309,597,402 | 309,597,402 | N/A | N/A | 331,683,753 | 323,806,168 | 290,050,854 | 297,511,369 |

| 1.3 Health Security | 61,360,077 | 61,360,077 | N/A | N/A | 67,620,506 | 69,155,991 | 66,895,158 | 67,972,376 |

| Subtotal | 481,785,537 | 481,785,537 | N/A | N/A | 516,536,073 | 509,936,257 | 468,539,790 | 482,111,974 |

| Internal Services | 90,149,394 | 90,149,394 | N/A | N/A | 110,250,932 | 97,166,297 | 90,677,238 | 90,968,166 |

| Total | 571,934,931 | 571,934,931 | N/A | N/A | 626,787,005 | 607,102,554 | 559,217,028 | 573,080,140 |

The increase in actual spending in 2017–18 is primarily due to the funding of: the one year investment in Indigenous Early Learning and Child Care Infrastructure and Programming; Adapting to the Impacts of Climate Change; Strengthening the Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy; Government advertising programs (horizontal item); and re-profiling of funding to Acquire Medical Countermeasures for Smallpox and Anthrax Preparedness.

Actual expenditures in 2016–17 were lower, compared to 2015–16, primarily due to the transfer to Global Affairs Canada of the assessed contribution to the Pan American Health Organization, and the funding re-profile for Ebola Preparedness and Response Initiatives to Protect Canadians at Home and Abroad.

Actual human resources

| Programs and Internal Services | 2015–16 Actual full-time equivalents |

2016–17 Actual full-time equivalents |

2017–18 Planned full-time equivalents |

2017–18 Actual full-time equivalents |

2018–19 PlannedFootnote b full-time equivalents |

2019–20 PlannedFootnote b full-time equivalents |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Public Health Infrastructure | 704 | 743 | 735 | 698 | N/A | N/A |

| 1.2 Health Promotion and Disease Prevention | 867 | 795 | 829 | 775 | N/A | N/A |

| 1.3 Health Security | 300 | 314 | 312 | 306 | N/A | N/A |

| Subtotal | 1,871 | 1,852 | 1,876 | 1,779 | N/A | N/A |

| Internal Services | 271 | 276 | 597 | 296 | N/A | N/A |

| Total | 2,142 | 2,127 | 2,473 | 2,075 | N/A | N/A |

The variance in FTE utilization is mainly due to the annual transfer of resources from PHAC to HC under the Health Portfolio Shared Services Partnership Agreement.

Expenditures by vote

For information on PHAC's organizational voted and statutory expenditures, consult the Public Accounts of Canada 2018.

Government of Canada spending and activities

Information on the alignment of PHAC's spending with the Government of Canada's spending and activities is available in the GC InfoBase.

Financial statements and financial statements highlights

Financial statements

PHAC's financial statements (unaudited) for the year ended March 31, 2018, are available on the PHAC website.

Financial statements highlights

| Financial information | 2017–18 Planned results |

2017–18 Actual |

2016–17 Actual |

Difference (2017–18 actual minus 2017–18 planned) |

Difference (2017–18 actual minus 2016–17 actual) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total expenses | 601,137,051 | 634,072,380 | 583,067,773 | 32,935,329 | 51,004,607 |

| Total revenues | 13,976,772 | 14,882,681 | 14,252,180 | 905,909 | 630,501 |

| Net cost of operations before government funding and transfers | 587,160,279 | 619,189,699 | 568,815,593 | 30,029,420 | 50,374,106 |

PHAC's 2017–18 total actual expenses were $634,072,380, which was an increase of $32,935,329 or 5.5% compared to 2017–18 planned results.

There was an increase of $51,004,607 or 8.7% in actual expenses from 2016–17 to 2017–18 primarily due to the funding of: the one year investment in Indigenous Early Learning and Child Care Infrastructure and Programming; Adapting to the Impacts of Climate Change; Strengthening the Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy; Government advertising programs (horizontal item); and re-profiling of funding to Acquire Medical Countermeasures for Smallpox and Anthrax Preparedness.

PHAC's total actual revenues, primarily from the Shared Services Partnership with Health Canada, were $14,882,681 in 2017–18, representing an increase of $630,501 or 4.4% from prior year actual revenues.

The difference between planned results and actual revenues was primarily due to the recognition of Health Canada payments as revenues to PHAC for services provided to the Agency under the Shared Services Partnership Agreement and not Revenues Earned on Behalf of Government.

| Financial Information | 2017–18 | 2016–17 | Difference (2017–18 minus 2016–17) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total net liabilities | 112,496,607 | 95,786,120 | 16,710,487 |

| Total net financial assets | 90,742,454 | 74,905,965 | 15,836,489 |

| Departmental net debt | 21,754,154 | 20,880,156 | 873,998 |

| Total non-financial assets | 101,967,115 | 106,108,381 | (4,141,266) |

| Departmental net financial position | 80,212,961 | 85,228,225 | (5,015,264) |

The decrease in net financial position from 2016–17 to 2017–18 is primarily due to the increase in acquisition, and accumulated amortization, of tangible capital assets in 2017–18.

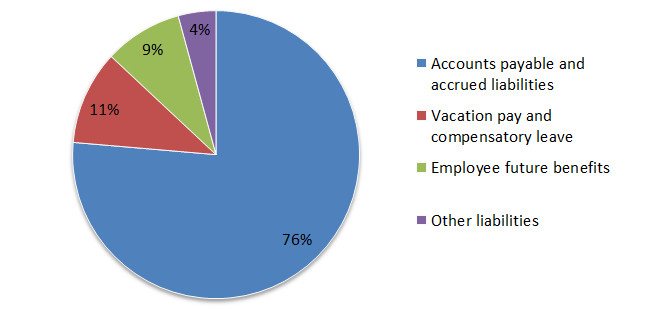

Liability by type

Text Description

Total liabilities:

- Accounts payable and accrued liabilities represented $85,907,349 (76%);

- Vacation pay and compensatory leave represented $11,936,678 (11%);

- Employee future benefits represented $9,876,966 (9%); and

- Other liabilities represented $4,773,494 (4%).

Total liabilities were $112,496,607, an increase of $16,710,487 (17%) over the previous year's total of $95,786,120. The variance was primarily due to an increase $15,972,563 in accounts payable and accrued liabilities and an increase of $847,687 in vacation pay and compensatory leave.

Of the total liabilities:

- Accounts payable and accrued liabilities represented $85,907,349 (76%);

- Vacation pay and compensatory leave represented $11,936,678 (11%);

- Employee future benefits represented $9,876,966 (9%); and

- Other liabilities represented $4,773,494 (4%).

Asset by type

Text Description

Total assets:

- Due from Consolidated Revenue Fund represented $77,962,854 (39%);

- Accounts receivable and advances represented $18,187,023 (9%); and

- Tangible capital assets represented $101,967,115 (52%).

Total assets were $192,709,569, an increase of $11,695,223 (6.5%) over the previous year's total of $181,014,345. This variance is primarily due to an increase in funds due from the Consolidated Revenue Fund, variations from employee future benefits and offset by a decrease in tangible capital assets, explained by accumulated amortization net of new acquisitions.

Of the total assets:

- Due from Consolidated Revenue Fund represented $77,962,854 (39%);

- Accounts receivable and advances represented $18,187,023 (9%); and

- Tangible capital assets represented $101,967,115 (52%).

Supplementary information

Corporate information

Organizational profile

Appropriate minister: The Honourable Ginette Petitpas Taylor, P.C., M.P.

Institutional head: Siddika Mithani, Ph.D.

Ministerial portfolio: Health

Enabling instruments: Public Health Agency of Canada Act, Department of Health Act, Emergency Management Act, Quarantine Act, Human Pathogens and Toxins Act, Health of Animals Act, Federal Framework on Lyme Disease Act, and the Federal Framework for Suicide Prevention Act.

Year of incorporation / commencement: 2004

Other: In June 2012, the Deputy Heads of HC and PHAC signed a Shared Services Partnership Framework Agreement. Under this agreement, each organization retains responsibility for a different set of internal services and corporate functions. These include human resources, real property, information management / information technology, security, internal financial services, communications, emergency management, international affairs, internal audit services, and evaluation services.

Reporting framework

PHAC's Strategic Outcome and Program Alignment Architecture of record for 2017–18 are shown below:

- 1. Strategic Outcome: Protecting Canadians and empowering them to improve their health

- 1.1 Program: Public Health Infrastructure

- 1.1.1 Sub-Program: Public Health Workforce

- 1.1.2 Sub-Program: Public Health Information and Networks

- 1.1.3 Sub-Program: Public Health Laboratory Systems

- 1.2 Program: Health Promotion and Disease Prevention

- 1.2.1 Sub-Program: Infectious Disease Prevention and Control

- 1.2.1.1 Sub-Sub-Program: Immunization

- 1.2.1.2 Sub-Sub-Program: Infectious and Communicable Disease

- 1.2.1.3 Sub-Sub-Program: Food-borne, Environmental and Zoonotic Infectious Disease

- 1.2.2 Sub-Program: Conditions for Healthy Living

- 1.2.2.1 Sub-Sub-Program: Healthy Child Development

- 1.2.2.2 Sub-Sub-Program: Healthy Communities

- 1.2.3 Sub-Program: Chronic (non-communicable) Disease and Injury Prevention

- 1.2.1 Sub-Program: Infectious Disease Prevention and Control

- 1.3 Program: Health Security

- 1.3.1 Sub-Program: Emergency Preparedness and Response

- 1.3.2 Sub-Program: Border Health Security

- 1.3.3 Sub-Program: Biosecurity

- Internal Services

- 1.1 Program: Public Health Infrastructure

Supporting information on lower-level programs

Supporting information on results, financial and human resources relating to PHAC's lower-level programs is available on the GC InfoBase.

Supplementary information tables

The following supplementary information tables are available on PHAC's website.

- Departmental Sustainable Development Strategy

- Details on transfer payment programs of $5 million or more

- Evaluations

- Fees

- Horizontal initiatives

- Internal audits

- Response to parliamentary committees and external audits

- Status report on projects operating with specific Treasury Board approval

Federal tax expenditures

The tax system can be used to achieve public policy objectives through the application of special measures such as low tax rates, exemptions, deductions, deferrals and credits. The Department of Finance Canada publishes cost estimates and projections for these measures each year in the Report on Federal Tax Expenditures. This report also provides detailed background information on tax expenditures, including descriptions, objectives, historical information and references to related federal spending programs. The tax measures presented in this report are the responsibility of the Minister of Finance.

Organizational contact information

Stephen Bent

Director General, Office of Strategic Policy and Planning

Public Health Agency of Canada

130 Colonnade Road

Ottawa, ON K1A 0K9

Telephone: 613-948-3249

stephen.bent@canada.ca

Appendix: definitions

- appropriation

- Any authority of Parliament to pay money out of the Consolidated Revenue Fund.

- budgetary expenditures

- Operating and capital expenditures; transfer payments to other levels of government, organizations or individuals; and payments to Crown corporations.

- Departmental Plan

- A report on the plans and expected performance of appropriated departments over a three-year period. Departmental Plans are tabled in Parliament each spring.

- Departmental Results Report

- A report on an appropriated department's actual accomplishments against the plans, priorities and expected results set out in the corresponding Departmental Plan.

- evaluation

- In the Government of Canada, the systematic and neutral collection and analysis of evidence to judge merit, worth or value. Evaluation informs decision making, improvements, innovation and accountability. Evaluations typically focus on programs, policies and priorities and examine questions related to relevance, effectiveness and efficiency. Depending on user needs, however, evaluations can also examine other units, themes and issues, including alternatives to existing interventions. Evaluations generally employ social science research methods.

- experimentation

- Activities that seek to explore, test and compare the effects and impacts of policies, interventions and approaches, to inform evidence-based decision-making, by learning what works and what does not.

- full-time equivalent

- A measure of the extent to which an employee represents a full person-year charge against a departmental budget. Full-time equivalents are calculated as a ratio of assigned hours of work to scheduled hours of work. Scheduled hours of work are set out in collective agreements.

- gender-based analysis plus (GBA+)

- An analytical approach used to assess how diverse groups of women, men and gender-diverse people may experience policies, programs and initiatives. The "plus" in GBA+ acknowledges that the gender-based analysis goes beyond biological (sex) and socio-cultural (gender) differences. We all have multiple identity factors that intersect to make us who we are; GBA+ considers many other identity factors, such as race, ethnicity, religion, age, and mental or physical disability. Examples of GBA+ processes include using data disaggregated by sex, gender and other intersecting identity factors in performance analysis, and identifying any impacts of the program on diverse groups of people, with a view to adjusting these initiatives to make them more inclusive.

- government-wide priorities

- For the purpose of the 2017–18 Departmental Results Report, those high-level themes outlining the government's agenda in the 2015 Speech from the Throne, namely: Growth for the Middle Class; Open and Transparent Government; A Clean Environment and a Strong Economy; Diversity is Canada's Strength; and Security and Opportunity.

- horizontal initiative

- An initiative where two or more departments are given funding to pursue a shared outcome, often linked to a government priority.

- internal auditFootnote 1

- An independent, objective assurance and consulting activity designed to add value and improve an organization's operations. It helps an organization accomplish its objectives by bringing a systematic, disciplined approach to evaluate and improve the effectiveness of risk management, control, and governance processes.

- Management, Resources and Results Structure

- A comprehensive framework that consists of an organization's inventory of programs, resources, results, performance indicators and governance information. Programs and results are depicted in their hierarchical relationship to each other and to the Strategic Outcome(s) to which they contribute. The Management, Resources and Results Structure is developed from the Program Alignment Architecture.

- non-budgetary expenditures

- Net outlays and receipts related to loans, investments and advances, which change the composition of the financial assets of the Government of Canada.

- performance

- What an organization did with its resources to achieve its results, how well those results compare to what the organization intended to achieve, and how well lessons learned have been identified.

- performance indicator

- A qualitative or quantitative means of measuring an output or outcome, with the intention of gauging the performance of an organization, program, policy or initiative respecting expected results.

- performance reporting

- The process of communicating evidence based performance information. Performance reporting supports decision making, accountability and transparency.

- plan

- The articulation of strategic choices, which provides information on how an organization intends to achieve its priorities and associated results. Generally a plan will explain the logic behind the strategies chosen and tend to focus on actions that lead up to the expected result.

- planned spending

- For Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports, planned spending refers to those amounts that receive Treasury Board approval by February 1. Therefore, planned spending may include amounts incremental to planned expenditures presented in the Main Estimates.

A department is expected to be aware of the authorities that it has sought and received. The determination of planned spending is a departmental responsibility, and departments must be able to defend the expenditure and accrual numbers presented in their Departmental Plans and Departmental Results Reports. - priority

- A plan or project that an organization has chosen to focus and report on during the planning period. Priorities represent the things that are most important or what must be done first to support the achievement of the desired Strategic Outcome(s) or Departmental Results.

- program

- A group of related resource inputs and activities that are managed to meet specific needs and to achieve intended results and that are treated as a budgetary unit.

- Program Alignment Architecture

- A structured inventory of an organization's programs depicting the hierarchical relationship between programs and the Strategic Outcome(s) to which they contribute.

- result

- An external consequence attributed, in part, to an organization, policy, program or initiative. Results are not within the control of a single organization, policy, program or initiative; instead they are within the area of the organization's influence.

- statutory expenditures

- Expenditures that Parliament has approved through legislation other than appropriation acts. The legislation sets out the purpose of the expenditures and the terms and conditions under which they may be made.

- Strategic Outcome

- A long term and enduring benefit to Canadians that is linked to the organization's mandate, vision and core functions.

- sunset program

- A time limited program that does not have an ongoing funding and policy authority. When the program is set to expire, a decision must be made whether to continue the program. In the case of a renewal, the decision specifies the scope, funding level and duration.

- target

- A measurable performance or success level that an organization, program or initiative plans to achieve within a specified time period. Targets can be either quantitative or qualitative.

- voted expenditures

- Expenditures that Parliament approves annually through an Appropriation Act. The Vote wording becomes the governing conditions under which these expenditures may be made.

Reference

- Reference 1

-

The Institute of Internal Auditors – North America.

Endnotes

- Endnote 1

-

A One Health approach acknowledges the interconnection between the health of humans, animals, and the environment, and the need for collaborative efforts to improve the health for all.

- Endnote 2

-

2017–18 data are not yet available.

- Endnote 3

-

The reporting year is 2016–17 as 2017–18 data are not yet available.

- Endnote 4

-

These sessions are intended to help provide initial support to someone who may be developing a mental health problem or is experiencing a mental health crisis. As well, the sessions are intended to improve an employee's knowledge of mental disorders, reduce stigma, and increase the amount of help provided to others.

- Endnote 5

-

The planned spending for 2018–19 to 2020–21 is not available due to the transition to the Departmental Results Framework. Planned spending for these years is available in PHAC's 2018–19 Departmental Plan.

Page details

- Date modified: