Chapter 16-20 - Canadian Biosafety Handbook, Second Edition

As of April 1, 2023, the Canadian Biosafety Standard, Second Edition (CBS2), referenced in this document, is no longer in effect. The Canadian Biosafety Handbook is currently being updated to align with the Canadian Biosafety Standard, Third Edition. We will communicate the publication of this update through the Biosafety and Biosecurity for Pathogens and Toxins News.

[Previous page] [Table of Contents] [Next page]

Chapter 16 - Waste Management

Waste management is an integral component of a biosafety program, and comprises policies, plans, and procedures to address all aspects of waste management, including decontamination and disposal. Waste leaving the containment zone may be destined for disposal, movement or transportation to a designated decontamination area outside of the containment zone, or transported off-site for decontamination via a third-party biohazardous waste disposal facility (e.g., incineration, steam sterilization). Even if the waste has been thoroughly and effectively decontaminated prior to removal from the containment zone, it may not be acceptable to simply direct it to the normal waste disposal stream for eventual transfer to a local landfill. Depending on the type of waste material, additional waste management considerations or requirements specified by the provincial, territorial, or local (i.e., municipal) authorities may also apply and should be consulted and complied with when establishing and implementing a waste management program. The requirements for waste management are specified in Matrix 4.8 of the Canadian Biosafety Standard (CBS), 2nd Edition.Footnote 1

Canada-wide guidelines exist for the management of certain types of waste (e.g., the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment [CCME] Guidelines for the Management of Biomedical Waste in Canada); however, these are not enforceable unless they are adopted by provincial legislation or municipal by-laws.Footnote 2 Local by-laws may be more stringent than the guidelines recommended by CCME. Standards such as Canadian Standards Association (CSA) Standard CSA Z317.10, Handling of Waste Materials in Health Care Facilities and Veterinary Health Care Facilities, may also be reviewed and considered when developing and implementing a sound waste management program.Footnote 3

Standard operating procedures (SOPs) for waste disposal are developed to support disposal of solid and liquid hazardous material in a manner that minimizes the risk of harm to personnel, the community, and the environment. The SOPs describe all aspects of waste disposal, including handling procedures, from the classification and segregation of infectious waste to decontamination method(s), to storage and disposal. Inclusion of waste disposal SOPs in the Biosafety Manual enables personnel to consult protocols as needed. Some aspects to consider when developing the waste management SOPs are the quantity and type of waste that will be generated, as well as the availability of decontamination systems. Decontaminating all contaminated or potentially contaminated waste prior to disposal minimizes the risk of introducing the infectious pathogens or toxins used in the containment zone into the environment. Failure to follow SOPs can result in the unintentional release of infectious material or toxins from the containment zone, or personnel exposure. It is the responsibility of containment zone personnel to ensure that proper procedures are followed and that containment is not breached. It is also important to note that containment zone personnel remain accountable for all waste transported off-site for decontamination, until the waste has been effectively decontaminated. Shipping records, validation reports, and records of verification of decontamination equipment used by third-party waste disposal companies can be maintained to demonstrate compliance with decontamination requirements specified in Matrices 4.8 and 5.1 of the CBS. Accountability considerations are discussed in Chapter 19.

The first step to improving a waste management program is to determine if there is a way to reduce the amount of waste generated. This can be as simple as minimizing the amount of packaging (e.g., cardboard boxes) brought into the containment zone. All manipulations and processes that will generate contaminated waste should be identified, and the waste categorized according to type. Developing specific handling procedures for each type of waste generated in the containment zone supports disposal of all waste materials in a safe manner. The choice of decontamination method is determined by the nature of the infectious material or toxin and the nature of the item being decontaminated. Decontamination methods are discussed in Chapter 15.

16.1 Biomedical Waste

Biomedical waste can be defined as waste generated in human and animal health care facilities, medical or veterinary research and training facilities, clinical testing or research laboratories, as well as vaccine production facilities. Biomedical waste is segregated from the general waste stream as it requires decontamination prior to disposal. Most Canadian jurisdictions have prepared or are preparing guidelines or regulations for the management of biomedical waste. The treatment procedures used at each facility are subject to the standards in place for that province or territory. CCME has also developed Canada-wide guidelines for defining, handling, treating, and disposing of biomedical waste: the Guidelines for the Management of Biomedical Waste in Canada. The intent of these guidelines is to promote uniform practices and set minimum standards for managing biomedical waste in Canada. Further considerations on the storage and disposal of biomedical waste can be found in Section 16.2.

Waste resulting from normal animal husbandry (e.g., bedding, litter, feed, manure) where the animals are not known to carry a pathogen, and waste that is controlled under the Health of Animals Act (HAA), are not considered to be biomedical in nature; however, the same principles of segregation and disposal can be applied.Footnote 4 CCME categorizes biomedical waste into five types, described below, which the provinces and territories can use to develop their own provincial/territorial requirements.

16.1.1 Human Anatomical Waste

Human anatomical waste consists of all human tissues, organs, and body parts, excluding hair, nails, and teeth. Even after disinfection or decontamination, human anatomical waste is still considered biomedical waste and may require special means of disposal depending on applicable provincial, territorial, and local legislation.

16.1.2 Animal Waste

Animal waste consists of all animal anatomical waste (carcasses, tissues, organs, body parts), bedding contaminated with infectious organisms, blood and blood products, items highly contaminated with blood, and body fluids removed for diagnosis or removed during surgery, treatment, or autopsy. Hair, nails, teeth, hooves, and feathers are not considered animal waste. Even after disinfection or decontamination, animal waste is still considered biomedical waste and may require special means of disposal depending on applicable provincial, territorial, and local legislation.

16.1.3 Microbiology Laboratory Waste

Microbiology laboratory waste consists of cultures, stocks, microorganism specimens, prions, toxins, live or attenuated vaccines, human and animal cell cultures, and any material that has come in contact with one of these. Inactivation of pathogens and toxins prior to disposal is a critical step in preventing release of harmful material into the environment. Microbiology laboratory waste is no longer considered biomedical waste once it has been effectively decontaminated.

16.1.4 Human Blood and Body Fluid Waste

Human blood and body fluid waste consist of all human blood or blood products, all items saturated with blood, any body fluid contaminated with blood, and body fluids removed for diagnosis during surgery, treatment, or autopsy. This does not include urine or feces, as per the CCME guideline. Human blood and body fluid waste is no longer considered biomedical waste once it has been effectively decontaminated.

16.1.5 Sharps Waste

Sharps waste consists of needles, syringes, blades, or glass contaminated with infectious material and capable of causing puncture wounds or cuts. This can include pipettes and pipette tips that have come into contact with infectious material or toxins, unless they have been decontaminated prior to disposal. Using puncture-resistant containers located close to the point of use minimizes the risk of injury during handling. Sharps waste may be reduced by product substitution for some applications. Sharps waste is no longer considered biomedical waste once it has been effectively decontaminated.

16.2 Storage and Disposal of Biomedical Waste

Decontamination of all biomedical waste prior to disposal in the regular waste stream is essential to the protection of public health, animal health, and the environment. It is important to segregate and dispose of biomedical waste near the point that the waste is generated. For example, it is recommended that unbreakable discard containers (e.g., pans, jars) be placed at every workstation to collect microbiological laboratory waste such as contaminated pipette tips. Some types of pathogens, such as prions, are not inactivated by decontamination processes that would be effective against most microorganisms; therefore, prion-contaminated waste should be segregated from other types of infectious waste. In facilities where multiple types of biomedical waste are generated, colour-coded waste holding bags or containers can be used to differentiate between types of waste.

It is important that the waste container used is suitable for the type of infectious waste generated. Plastic bags, single-use containers (e.g., cardboard), or reusable containers have different applications. Human anatomical waste, blood and body fluids, and animal waste should be placed in impervious, leak- and tear-resistant waste bags. Removing sharp objects (e.g., needles, capillary tubes, pipette tips) from tissues before placing the tissues in waste bags will prevent the bags from being perforated. Waste bags should be sealed, placed in leak-proof containers, and stored in a freezer, refrigerator, or cold room to await decontamination. Reusable containers may be used, provided that they are decontaminated and cleaned after every use. Sharps waste is disposed of directly into a puncture-resistant container in accordance with National Standard of Canada (CAN)/CSA Standard CAN/CSA Z316.6, Sharps Injury Protection- Requirements and Test Methods- Sharps Containers.Footnote 5 Broken glassware should never be handled with gloved or bare hands. Forceps, tongs or a dustpan should be used to pick up broken glassware and a wet paper towel held in tongs should be used to pick up tiny glass particles.

If waste is not decontaminated and disposed of immediately, it may be stored temporarily provided that it is in a designated area that is separate from other storage areas and clearly marked with a biohazard symbol. Some types of waste (e.g., human anatomical waste, animal waste) need to be stored in a refrigerated area to prevent putrefaction. Once materials have been decontaminated on-site, the biohazard symbol on the receptacle is removed or defaced to indicate that the infectious material has been inactivated. Decontaminated material may be disposed of as regular waste in areas of heavy traffic or public areas, provided that the facility has specific labelling procedures in place. In other cases, it may be necessary to transport waste off-site for decontamination and disposal. Whether the waste will be decontaminated on-site or off-site, placing waste in appropriate disposal containers promptly and labelling the containers accordingly will keep all infectious waste segregated from regular waste until decontamination and disposal.

Limiting the movement of waste disposal containers to the point of use in the work area, storage (e.g., dedicated area, cold room) or disposal areas, and connecting corridors, will help minimize the risk of release of pathogens and toxins, and personnel exposure. More information on the movement and transport of biological material can be found in Chapter 20.

References

- Footnote 1

- Government of Canada. (2015). Canadian Biosafety Standard (2nd ed.). Ottawa, ON, Canada: Government of Canada.

- Footnote 2

- Canadian Council of the Ministers of the Environment. (1992). Guidelines for the Management of Biomedical Waste in Canada. Mississauga, ON, Canada: Canadian Standards Association.

- Footnote 3

- CSA Z317.10-15, Handling of health care waste materials. (2015). Mississauga, ON, Canada: Canadian Standards Association.

- Footnote 4

- Health of Animals Act (S.C. 1990, c. 21). (2015).

- Footnote 5

- CAN/CSA Z316.6-14 Sharps Injury Protection - Requirements and Test Methods - Sharps Containers. (2014). Mississauga, ON, Canada: Canadian Standards Association.

Chapter 17 - Emergency Response Plan

It is critical that all containment zones address situations where biosafety or biosecurity issues may arise as a result of an emergency. Emergency situations may include incidents or accidents, medical emergencies, fire, spills (e.g., chemical, biological, radiological), power failure, animal escape, discrepancy or violation of an inventory of pathogens or toxins, failure of primary containment devices (e.g., biological safety cabinet [BSC]), loss of containment (e.g., heating, ventilation, and air conditioning [HVAC] system failure), or natural disasters. The emergency response plan (ERP), based on an overarching risk assessment, describes the procedures relevant to any emergency situation and is essential to protect lives, property, and the environment. The ERP will identify foreseeable emergency scenarios and describe response measures that are proportional to the scale and nature of the emergency. The plan should take into account the hazards in the geographical area (e.g., severe weather or natural disasters). The ERP may also include contingency plans to continue operations in a safe and secure manner. The minimum requirements for an ERP in regulated containment zones are specified in Matrix 4.9 of the Canadian Biosafety Standard (CBS), 2nd Edition.Footnote 1 There are many additional resources widely available to assist in the development of an ERP.Footnote 2Footnote 3Footnote 4Footnote 5

17.1 Emergency Response Plan Development

When developing the ERP for containment zones, collaboration with experienced facility staff will ensure that the final plan is comprehensive and integrated with facility-wide plans, where appropriate. Personnel involved in ERP development may include facility administrators, scientific directors, principal investigators, laboratory personnel, maintenance and engineering support staff, biological safety officers (BSOs), and facility security officials. Coordination with local first responder organizations, including police, fire department, and paramedics, is recommended.

The ERP should be specifically tailored to the organization, facility, and containment level and will address the safety of emergency personnel who may enter the containment zone, particularly at high containment levels. It may also be advisable to inform emergency personnel of the type of infectious material in use within the containment zone. Mitigation strategies to address the biosecurity issues that arise from emergency personnel who may have access to restricted infectious material, toxins, or sensitive information while responding to an emergency should be considered.

The ERP may include, but is not limited to, the following:

- personnel responsible for the development, implementation, and verification of the ERP;

- consultation plan for coordination with local emergency response organizations and local hospitals or health care facilities, as appropriate;

- risk assessment tools allowing the identification of emergency scenarios and mitigation strategies;

- emergency exit/evacuation routes, avoiding evacuation through higher containment zones;

- protocols for the safe removal, transport, and treatment of contaminated personnel and materials;

- consideration of emergencies that may take place during and outside of regular working hours;

- emergency access procedures, considering the need to override existing access controls when appropriate, and the need to keep a record of emergency response personnel who enter the containment zone; including any contingency plans or mitigation strategies to maintain biosecurity during these situations;

- contingency plans to be implemented to ensure essential operations continue safely and securely;

- emergency training programs, including education on the safe and effective use of emergency equipment;

- emergency exercise plans, including the type and frequency of exercises to be conducted specific to the facility's risks;

- emergency (i.e., incident/accident) reporting and investigation procedures;

- a description of the type of emergency equipment available in the containment zone (e.g., first aid kits, spill kits, eyewash and shower stations) and directions for proper use; and

- procedures for the notification of key personnel and the appropriate federal regulatory agencies.

17.2 Emergency Response Plan Implementation

Once developed, the ERP or a summary of the plan can be included in a facility's Biosafety Manual and communicated to all facility personnel appropriately. Training of personnel on the emergency procedures is essential to make certain that personnel, particularly new personnel, are aware of and familiar with the procedures to follow prior to an actual emergency event. This is to be incorporated into the facility's training program (CBS Matrix 4.3). Annual refresher training for existing personnel is considered appropriate to maintain knowledge of emergency procedures, although more frequent training may be indicated by a risk assessment or training needs assessment. Structured and realistic exercises are useful tools to verify that personnel demonstrate knowledge of the ERP, understand its importance, can provide assurance of its effectiveness, and identify any deficiencies or areas for improvement. Biosecurity-specific procedures and scenarios can be included (e.g., response procedures in case of theft or loss of a pathogen or toxin, or theft, loss, or sabotage of containment equipment or systems, or communication arrangements with local law enforcements or authorities). In addition, all aspects of the ERP (e.g., development, implementation, training, exercises) should be thoroughly documented for training purposes and for review during an audit or inspection.

It is always important to revise the ERP and keep it up to date with respect to any changes within the containment zone or the surrounding environment (e.g., use of a new pathogen in the containment zone, a catastrophic weather event). It is the responsibility of the facility to determine the frequency of ERP reviews, assessments, and updates. Following an emergency in which the ERP was activated, it is recommended that the ERP be reviewed to address any newly identified deficiencies.

17.3 Spill Response

Spills are the most common incidents with the potential for exposure of personnel to pathogens or toxins, or their release from containment. Spills can contaminate surfaces, equipment, samples, and workers. The decontamination protocol used depends on where the spill occurred and its size (volume).

When a spill occurs outside a BSC, the potential exists for all those present in the work area to be exposed to infectious aerosols or aerosolized toxins. Personal safety is the top priority, but it is also important to prevent the spread of contamination outside the immediate area and the containment zone. Having a pre-assembled biological spill kit on hand that contains all items needed to contain and clean up a spill (e.g., gloves, disposable gowns and shoe covers, respirator, effective disinfecting agent, paper towels or spill pillows, dustpan, broom, tongs, waste bags, and a waterproof copy of spill clean-up standard operating procedures [SOPs]) will facilitate timely and effective spill response. It is important that personnel are adequately trained to follow spill response procedures.

17.3.1 General Spill Clean-Up Procedure

After the risk of injury has been controlled, the following steps are recommended to contain a spill of infectious material and decontaminate the area affected by a spill:Footnote 6

- Remove any contaminated or potentially contaminated clothing and personal protective equipment (PPE).

- Contaminated personnel doff their outer layer of PPE and any contaminated or potentially contaminated clothing and follow normal exit procedure, including handwashing. In the case of a large spill, personnel remove the outer layer of protection in proximity to the spill. Depending on a local risk assessment (LRA) and SOPs, personnel may proceed to a change room to remove the inner layer of PPE, which is placed into an autoclave bag for decontamination. Personnel proceed to wash any other potentially contaminated parts of their body.

- Notify all staff in the immediate vicinity that a spill has occurred and to leave the area.

- Exposed persons should be referred for medical attention. The laboratory supervisor or responsible authority should be informed without delay.

- Allow aerosols to settle (e.g., for 30 minutes) before re-entering the area. If the laboratory does not have a central air exhaust, entry should be delayed (e.g. for 24 hours) to allow sufficient air exchanges to exhaust any aerosols and to allow heavier particles to settle. Signs should be posted indicating that entry is forbidden.

- Don fresh PPE appropriate to the risk, which may include gloves, protective clothing, face and eye protection, and a respirator.

- Assemble required clean-up materials (e.g., biological spill kit) and bring them to the site of the spill.

- Cover the spill with cloth or paper towels to contain it.

- Pour an appropriate disinfectant (i.e., sufficient concentration, effective against the pathogen(s) spilled, freshly prepared) starting at the outer margin of the spill area, and concentrically working toward the center, over the cloth or paper towels and the immediately surrounding area.

- After the appropriate contact time (i.e., for the pathogen and disinfectant), clear away the towels and debris. If there is broken glass or other sharps involved, use a dustpan or pieces of stiff cardboard to collect and deposit the material into a puncture-resistant container for disposal. Glass fragments should be handled with forceps. Dustpans can be autoclaved or placed in an effective disinfectant.

- Clean and disinfect the area of the spillage. If necessary, repeat the previous steps.

- Dispose of contaminated materials in a leak-proof, puncture-resistant waste disposal container.

- Once the spill clean-up is complete, as per the general spill clean-up procedure, personnel doff contaminated PPE and don clean PPE prior to returning to work in the laboratory.

- After disinfection, inform the appropriate internal authority (e.g., containment zone supervisor, BSO) that the site has been decontaminated.

- Depending on the nature and size of the spill, a complete room decontamination may be warranted.

17.3.2 Spill Inside a Biological Safety Cabinet

The size of the spill is determined by how far it spreads, and less by its volume. When a small spill occurs inside a BSC, the worker is not considered contaminated unless a splash or spillage has escaped the BSC; however, the gloves and sleeves may be contaminated. A large spill in a BSC may result in material escaping the BSC and the worker becoming contaminated. In this case, the outer layer of PPE is considered potentially contaminated and should be removed at the BSC. The following general procedure is recommended for spills inside a BSC:

- Remove gloves and discard within the BSC. If two pairs are worn, discard the outermost layer. If sleeves are potentially contaminated, the lab coat or gown should also be removed. Fresh gloves should be donned and if necessary, also a fresh lab coat or gown.

- Leave the BSC blower on and the sash at the appropriate level.

- Follow the instructions outlined in Section 17.3.1 for general spill clean-up, keeping head outside the BSC at all times.

- Surface disinfect all objects before removing them from the BSC, or place them into bags for autoclaving. Remove contaminated gloves and dispose of them inside the cabinet.

- Place PPE into bags for autoclaving.

- If material has spilled through the grill of the BSC, pour disinfectant through the grill to flood the catch tray underneath.

- Wipe all inside surfaces with disinfectant.

- Raise the work surface, clean the catch tray, and then replace the work surface.

- Allow BSC to run for at least 10 minutes before resuming work or shutting down.

17.3.3 Spill Inside a Centrifuge

If a breakage occurs or is suspected while a centrifuge is running, the motor should be switched off and the centrifuge left closed (e.g., for 30 minutes) to allow aerosols to settle. Should a breakage be discovered only after the centrifuge has been opened, the lid should be replaced immediately and left closed (e.g., for 30 minutes).

- Inform the appropriate internal authority (e.g., containment zone supervisor, BSO).

- Follow the instructions outlined in Section 17.3.1 for general spill clean-up.

- If possible, use a non-corrosive disinfectant known to be effective against the pathogen concerned. Whenever possible, consult the centrifuge manufacturer's specifications on the unit to confirm the chemical compatibilities.

- All broken tubes, glass fragments, buckets, trunnions, and the rotor should be placed in a non-corrosive disinfectant (forceps are to be used to handle and retrieve glass and other sharps debris). Unbroken sealed safety cups may be placed in disinfectant and carried to a BSC to be unloaded.

- The centrifuge bowl should be swabbed with the same disinfectant, at the appropriate dilution, and then swabbed again, washed with water, and dried.

References

- Footnote 1

- Government of Canada. (2015). Canadian Biosafety Standard (2nd ed.). Ottawa, ON, Canada: Government of Canada.

- Footnote 2

- Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety. (2014). Emergency Response Planning Guide. Retrieved 11/03, 2015 from http://www.ccohs.ca/products/publications/emergency.html

- Footnote 3

- Public Safety Canada. (2010). Emergency Management Planning Guide: 2010-2011. Retrieved 11/03, 2015 from http://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/mrgnc-mngmnt-pnnng/mrgnc-mngmnt-pnnng-eng.pdf

- Footnote 4

- Government of Canada. (2015). Get Prepared. Retrieved 11/03, 2015 from http://www.getprepared.gc.ca.

- Footnote 5

- Tun, T., Sadler, K. E., & Tam, J. P. (2008). A Novel Approach for Development and Implementation of an Emergency Response Plan for the BSL-3 Laboratory Service in Singapore. Applied Biosafety. 13:158-163.

- Footnote 6

- World Health Organization. (2004). Laboratory Biosafety Manual (3rd ed.). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization.

Chapter 18 - Incident Reporting and Investigation

Though the terms "incident" and "accident" are often used interchangeably when referring to reporting procedures, a distinction should be made between the two words. An accident is an unplanned event that results in injury, harm, or damage. An incident is an event with the potential to cause injury, harm, or damage. Incidents include accidents, as well as near misses and other dangerous occurrences. In the Canadian Biosafety Standard (CBS), 2nd Edition, as well as in this volume, the term "incident" refers to all possible occurrences, including accidents, exposures (that may cause disease), laboratory acquired infections/intoxications (LAIs), containment failures, environmental releases (e.g., improperly treated waste sent to the sewer system), and biosecurity breaches (e.g., theft or intentional misuse of an infectious material or toxin) (illustrated in Figure 18-1).Footnote 1All incidents, even those seemingly minor, should set in motion the facility's internal incident reporting procedures as described in the Biosafety Manual and other appropriate protocols (e.g., incident investigation and documentation). The minimum requirements for incident investigation and reporting in regulated containment zones are specified in Matrix 4.9 of the CBS.

Protocols for incident reporting and investigation are an integral component of a facility's emergency response plan (ERP). Incidents need to be properly reported, documented, and investigated in order to learn from these events and to correct or address any problems or issues that may have caused the incident and prevent a recurrence, and to notify external authorities (i.e., the Public Health Agency of Canada [PHAC] or the Canadian Food Inspection Agency [CFIA]) when necessary. Exposures in a containment zone can occur via inhalation (e.g., breathing in infectious aerosols or aerosolized toxins), ingestion (e.g., contact of mouth with contaminated hands or materials), percutaneous inoculation (e.g., subcutaneous contamination by puncture, needlestick, or bite), or through absorption (e.g., entry through direct skin, eye, or mucous membrane contact). Incidents may be indicative of failures in containment systems, biosafety-related standard operational procedures (SOPs), training programs, or biosecurity systems; subsequent investigation enables containment zone personnel to identify these failures and take corrective action. Reporting and investigation procedures should be developed to complement or integrate with existing facility-wide programs (e.g., occupational health and safety). The ERP is discussed in more detail in Chapter 17.

Several standards are currently available to assist facilities in the development of incident reporting and investigation procedures. They include, but are not limited to, the British Standards Institution Occupational Health and Safety Assessment Series (OHSAS) 18001, Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems; the National Standard of Canada/Canadian Standards Association (CAN/CSA) CAN/CSA Z1000, Occupational Health and Safety Management; and CAN/CSA Z796, Accident Information.Footnote 2Footnote 3Footnote 4 The minimum requirements for incident reporting and investigation in regulated containment zones are specified in Matrix 4.9 of the CBS. Record retention requirements for incidents are specified in Matrix 4.10 of the CBS.

18.1 Incident Reporting

All incidents involving infectious material, infected animals, or toxins, such as a containment systems failure, an exposure to a human pathogen or toxin, or release of an animal pathogen, must be reported immediately to the appropriate facility personnel (e.g., containment zone supervisor, biological safety officer [BSO], licence holder in licensed facilities) (CBS Matrix 4.2). Moreover, all persons working under the authority of a licence are legally obligated to notify the appropriate facility personnel if they have reason to believe that an incident has occurred involving inadvertent release, inadvertent production, disease (i.e., any exposure incident), or a missing human pathogen or toxin (HPTA 15). It is important to promptly report incidents internally, within the facility, so that management (including the licence holder in licensed facilities) is made aware of the events, can implement immediate hazard reduction and mitigation strategies, and initiate a preliminary assessment to determine if an exposure has likely occurred (Figure 18-2 illustrates a decision chart to assist in the exposure assessment). As well, internal reporting initiates the facility's process to investigate the incident, determine the root cause(s), plan corrective actions, document outcomes (i.e., injury to personnel), and determine legislated notification requirements to regulatory authorities. In the event of certain types of incidents involving pathogens, infectious material, and toxins, personnel in facilities that are regulated by the PHAC and the CFIA are likewise obligated to notify or report to the appropriate regulatory authority. Regulated facilities are also required to develop and maintain documented procedures to define, record, and report incidents involving infectious material or toxins (CBS Matrix 4.1). These procedures should also comply with any additional applicable federal, provincial or territorial, and municipal regulations, as well as the organization's internal incident reporting and investigation requirements.

18.1.1 Incident Reporting to the Public Health Agency of Canada

Facilities that hold a licence to conduct controlled activities with human pathogens and toxins are obligated to notify the PHAC in the event of incidents and exposures in accordance with the Human Pathogens and Toxins Act (HPTA), and Human Pathogens and Toxins Regulations (HPTR), as previously described.Footnote 5Footnote 6 The functions of the BSO include communicating with the PHAC on behalf of the licence holder (HPTR 9[1]), which includes the required reporting of incidents. In accordance with the HPTA and HPTR, a licence holder is obligated to notify the PHAC without delay in the following scenarios:

- when a licence holder has reason to believe that a human pathogen or toxin has been released inadvertently from a facility (HPTA 12[1]);

- when a human pathogen or toxin that a person is not authorized to possess is inadvertently produced or otherwise comes into their possession (HPTA 12[2]);

- when a security sensitive biological agent (SSBA) is not received within 24 hours of the date and time when it was expected to be received (HPTR 9[1]);

- when there is reason to believe that a human pathogen or toxin has been stolen or is otherwise missing (HPTA 14);

- when an incident involving a human pathogen or toxin has caused, or may have caused, disease in an individual (i.e., any exposure incident) (HPTA 13); and

- as specified by any additional licence condition set out on the licence itself that describes an incident scenario that requires notification of the PHAC (HPTA 18[4]).

18.1.1.1 Notification of Exposures Involving Human Pathogens and Toxins

Infections that result from an exposure to pathogens or infectious material being handled in the containment zone are referred to as LAIs; this term also includes a disease caused by exposure to a toxin (i.e., intoxication) that is being handled in the containment zone. Exposure incidents are more encompassing, and include any incident involving a pathogen or toxin where infection or intoxication is likely to have occurred, and thereby a potential for disease (whether or not overt disease actually does develop). Under the HPTA Section 13, any incident resulting in an LAI (i.e., recognized disease) or an exposure (i.e., probable inhalation, ingestion, inoculation, or absorption) involving a Risk Group 2 (RG2), Risk Group 3 (RG3), or Risk Group 4 (RG4) human pathogen or toxin that occurs in a licensed facility must be reported to the PHAC without delay (i.e., as soon as the situation is under control and sufficient information has been gathered to report the preliminary details of the incident). This information can be submitted to the PHAC electronically through the Biosecurity Portal, accessible through the PHAC website (www.publichealth.gc.ca/pathogens), in an exposure notification report. This initial notification of the exposure incident captures brief information to describe the incident, the name of the pathogen or toxin involved, and other preliminary information relating to the incident, such as immediate mitigation measures and current status of the affected individual(s), if known. Personal identification of the affected individual(s) is not normally required, but may be requested in exceptional circumstances (e.g., to protect public health). An exposure follow-up report documenting the outcomes of the incident investigation is to be submitted to the PHAC within 15 or 30 days of the exposure notification report, depending on whether or not SSBAs were involved in the incident. The requirements regarding exposure reporting to the PHAC are specified in Matrix 4.9 of the CBS.

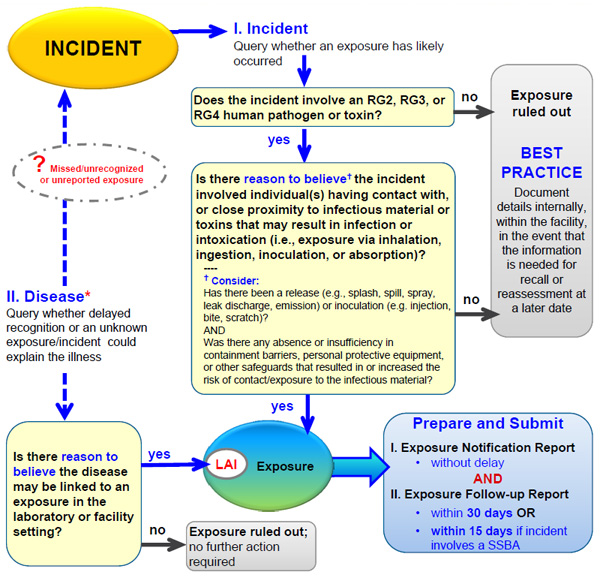

Figure 18-2 illustrates a decision chart to assist in the assessment of an incident to determine if an exposure is to be notified in accordance with HPTA Section 13. There are two scenarios: (I) a recognized incident where assessment is required to determine or rule out possible exposure(s) to human pathogens or toxins among one or more individuals involved in the incident; and, (II) a recognized disease in one or more facility personnel or other individuals (e.g., visitor, student) where assessment is appropriate to determine or rule out a possible missed, unrecognized, or unreported exposure incident that explains the illness.

Reporting to the PHAC is not necessary in the case of an incident in a licensed containment zone wherein the incident investigation and local assessment of facts has determined that exposure (i.e., infection or intoxication) is unlikely to have occurred as a result of the event. Reporting to the PHAC is also not necessary in the case of a recognized disease that is determined not likely to have been caused by an exposure incident in the containment zone. In this latter case, the incident investigation and local assessment of facts has ruled out exposure in the laboratory setting and determined that a community, travel-related, or other exposure setting is the most likely source of the disease. In addition, exposure incidents and LAIs that occur in containment zones or facilities that are exempt from the licence requirements under the HPTA and HPTR are not obligated to be reported to the PHAC, but may still be reported on a voluntary basis. Please contact the PHAC directly for more information on voluntary reporting of incidents.

18.1.1.2 Exposure Follow-Up Activity

The exposure follow-up report form, available from the PHAC, is an extension of the exposure notification report, wherein the preliminary incident details provided upon notification can be updated, added to and submitted electronically through the Biosecurity Portal in the exposure follow-up report. The design and format of the electronic report is intended to capture the outcomes of the incident investigation process. Ultimately, it serves to document key details on the incident, assist with conducting a root cause analysis, and record the corrective action plan aimed at mitigating the event and reducing the likelihood of a recurrence. An exposure follow-up report detailing the exposure incident investigation is to be submitted to the PHAC within 30 calendar days of submission of the initial exposure notification report for incidents, or within 15 calendar days if the incident involves an SSBA (CBS Matrix 4.9).

The PHAC reviews and analyzes information contained in exposure notification and follow-up reports to monitor for potential patterns, assess the potential significance for public health, and determine if any direct involvement by the PHAC is warranted. This decision may be based on consideration of factors such as risk group(s) of the human pathogens or toxins involved in the incident, the communicability of the human pathogens, the number of affected individuals, and the likelihood of spread to the community. Where it is deemed appropriate, the PHAC will contact the licence holder promptly to follow up on actions taken. Upon request, the PHAC can also assist with the assessment, investigation, and reporting process by providing guidance, subject matter expertise, or related support.

18.1.1.3 Annual Reporting of Incidents Involving Security Sensitive Biological Agents

As an additional condition of licence, licence holders authorized to work with SSBAs may be required to submit an annual report to the PHAC summarizing all incidents involving SSBAs that occurred during the previous 12 months (or a report indicating that no incidents have occurred). The annual report is to include: a summary of any incidents that have occurred within the past year, the root cause analysis for each incident, a description of any systemic biosafety concerns, and details of the corrective measures that have been implemented to address them. The annual report builds upon the regular incident reporting requirements by providing the PHAC with a better understanding of the frequency and potential causes of incidents involving SSBAs. Since detailed information on any exposure incident involving an SSBA will be reported via the required initial exposure notification report, and the exposure follow-up report submitted 15 calendar days later, this information does not need to be repeated in the SSBA annual report.

18.1.1.4 Exposure Reporting Program

All information on exposure and LAI incidents involving RG2, RG3, and RG4 human pathogens and toxins in licensed containment zones are to be submitted to the PHAC and thereby captured within the PHAC's Exposure Reporting Program database. This allows the PHAC to monitor developing trends, and may prompt the issuance of biosafety advisories as well as contribute to updates of biosafety best practices and training. Under normal circumstances, the PHAC does not gather confidential business or personal information with respect to incidents involving the exposure of an individual to a human pathogen or toxin; however, should such information be required, it is protected in accordance with applicable federal laws.

Information collected from exposure notification and follow-up reports documenting exposures or LAIs involving human pathogens and toxins is analyzed by the PHAC to help shape current and future biocontainment and biosafety practices in Canada.

18.1.2 Reporting to the Canadian Food Inspection Agency

The Health of Animals Act (HAA) sets out requirements for the notification of the CFIA in the event that an animal is discovered to be infected with pathogens causing, or showing signs of, a reportable disease or toxic substance.Footnote 7 The Schedule to the Reportable Diseases Regulations, and Schedules VII and VIII of the Health of Animals Regulations (HAR) list the reportable and notifiable diseases that affect terrestrial animals.Footnote 8Footnote 9 This may be of concern in an animal containment zone where an experimental animal is discovered to inadvertently carry or develop clinical signs of one the indicated diseases. Please contact the CFIA directly for more information on reportable and notifiable diseases.

Based on the conditions included on an animal pathogen import permit, any incident involving an animal pathogen, toxin, or other regulated infectious material in a facility to which that material was imported or transferred using an animal pathogen import permit or transfer authorization issued by the CFIA, or in a facility that has been certified by the CFIA, may require reporting to the CFIA. The CFIA will review the information surrounding the incident to verify that a release has not occurred and to ensure continued compliance with the CBS. To this end, information on incidents involving animal pathogens received by the PHAC may also be shared with the CFIA. The animal pathogen import permit may include further conditions on reporting to the CFIA. Please refer to the conditions of permit for further information.

18.2 Incident Investigation

Incident investigation is necessary to determine the root cause(s) of the incident, in other words, to identify the most basic or underlying reasons why the incident took place. Equally important, results of a thorough incident investigation, serve to determine and direct appropriate corrective actions to mitigate the current problem(s) as well as prevent similar incidents from occurring in the future. As such, incident investigation provides a crucial feedback mechanism to assist in the improvement of existing incident mitigation and prevention strategies. Incident investigation and reporting procedures to uncover and document these findings may include the following:

- defining potential incidents and the triggers for reporting and investigation;

- identifying personnel roles and responsibilities;

- outlining the reporting chain of command;

- defining the sequence of events and the subsequent root cause(s) that led or contributed to the incident;

- documenting the incident and providing the types and content of incident reports and templates;

- identifying the frequency and distribution of incident reports;

- identifying the corrective actions to prevent a recurrence of the incident;

- identifying opportunities for improvement;

- assessing the effectiveness of the preventive and corrective actions taken; and

- communicating the investigation results and the corrective actions taken to the appropriate parties (e.g., facility personnel, health and safety committee, senior management, regulatory authorities, and local law enforcement).

The extent and depth of the incident investigation may vary, depending on the severity of the incident or the level of concern associated with the pathogen or toxin involved (e.g., SSBA). Prior to commencing an investigation, the personnel responsible for this duty should be selected and identified. Depending on the nature and severity of the incident, one individual may be assigned to conduct the investigation or a team may be assembled for more complex scenarios. The investigator(s) should conduct the investigation with an open mind taking care to exclude any pre-conceived notions and opinions regarding the nature and cause of the incident. Incident investigation procedures should be reviewed and updated regularly so that they are current and effective. The investigation process is systematic and generally includes the stages outlined in the subsections below.

18.2.1 Initial Response

The initial response may include the provision of first aid or emergency services, assessing the severity of the incident (e.g., potential for loss of containment or infection), controlling the extent of the current hazard and preventing a secondary incident, identifying and preserving evidence, and notifying appropriate personnel. At this stage, an assessment is conducted to determine whether or not a pathogen or toxin has been released (e.g., as a result of a spill, splash, leak, spray, discharge, or emission) from a containment system or from the containment zone itself, and if it has, to implement measures to control and contain the released material and prevent any supplementary incidents. Incidents involving infectious materials require immediate reporting to the appropriate facility personnel (e.g., containment zone supervisor, BSO), and, depending on the type of incident, may also require external reporting as well (see Section 18.1). The extent and depth of the incident investigation may vary, depending on the severity of the incident.

18.2.2 Collection of Evidence and Information

The collection of evidence and accurate information is critical to any incident investigation. Photos, sketches, or videos may be used to capture a visual record of the evidence, including its location, and are useful for subsequent analysis. It is important to interview people who may have knowledge of what contributed to the incident and to do this as soon as possible to minimize any recall bias. Additionally, the collection of documentation pertaining to the incident may provide information relevant to the investigation. Documentation can be extensive and may include employee training records, maintenance logs, purchasing standards, SOPs, new employee and visitor orientation policies, and safe work practices.

18.2.3 Analysis and Identification of Root Causes

The analysis of the evidence and information to identify root causes is often achieved through an expanded version of the traditional questions: who, what, when, where, how, and why. Examples of these types of questions include the following:

- Who were the people involved in the incident (e.g., personnel, bystanders)?

- What infectious material or toxin was involved in the incident?

- When and where did the incident take place?

- How did the incident happen (i.e., what factors contributed to the incident)?

In the expanded use of the traditional questions, ask why each event in the incident scenario happened. Putting the "why" question in front of all the questions asked will help determine the basic causal factors and pathways that led to the incident. Through the cascading series of "why" questions, the underlying root cause(s) that led or contributed to the incident can be determined when there are no further answers. Considerations such as purchasing controls, training, and equipment operation should be taken into account when asking the "why" questions. It may also be advisable to question whether or not the incident was isolated or recurring, or accidental or intentional, especially where a breach of biosecurity has occurred (e.g., individual repeatedly removing SSBA samples without updating the sample inventory).

18.2.4 Development of Corrective and Preventive Action Plans

Developing corrective and preventive action plans assists in addressing the root causes of various incidents as well as identifying appropriate actions to prevent their recurrence. The investigation may identify biosafety or biosecurity elements that may have failed to prevent the incident and provide insight and opportunities that allow for their correction. Based on the investigation findings, the plans should identify actions to eliminate the immediate hazard (corrective plans) and mitigate the risk of the incident recurring (preventive plans). Both plans will also identify the personnel required to implement the actions and provide time frames for completion.

18.2.5 Evaluation and Continual Improvement

Once the corrective and preventive action plans have been implemented, it is important to review their effectiveness and confirm that the identified root causes are being effectively controlled.

The final stage of incident investigation involves ongoing program review to identify opportunities for improvement. This may be accomplished through the review of incident investigation reports, incident trends, and consultation with containment zone personnel or senior management. This should include a review of local risk assessments (LRAs) and SOPs to determine if revisions are required as a result of the incident. Where inadequate training was identified as a root cause, training materials should be updated accordingly and refresher training for personnel scheduled.

Figure 18-1: Visual Representation of Incidents Involving Pathogens and Toxins, including Exposures and Laboratory Acquired Infections/Intoxications (LAIs).

Text Equivalent - Figure 18-1

This figure depicts the various incidents involving pathogens and toxins, and shows those that can lead to exposure, which include: personal injury or illness; spill; animal escape; release; unauthorized entry into the containment zone; power failure; fire or explosion; flood or other crisis situation. Missing infectious material or toxin is the one incident that does not lead to exposure. Laboratory acquired infections and intoxications are depicted as a subset of exposures.

Figure 18-2: Decision Chart to Assist in the Assessment of an Incident to Determine if an Exposure has Occurred and if Notification of the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) is Required.

Text Equivalent - Figure 18-2

If an incident involved an RG3, RG3, or RG4 pathogen or toxin, and there is reason to believe that the incident involved one or more individuals' contact with, or close proximity to, infectious material or toxins that may result in infection or intoxication – that is, exposure via inhalation, ingestion, inoculation, or absorption – then an exposure occurred and an exposure notification report is to be prepared and submitted without delay, and an exposure follow-up report submitted within 30 days, or in the case of an SSBA, within 15 days. If the incident did not involve an RG2, RG3, or RG4 human pathogen or toxin, or if there is no reason to believe that contact or close proximity with pathogens or toxins may have resulted in infection or intoxication, then best practice dictates that the incident be documented internally within the facility in the event that the information is needed for recall or reassessment at a later date.

If a disease is detected and there is reason to believe that it may be linked to an exposure in the containment zone setting, then it is classified as an LAI and a previously missed or unreported exposure. In such a case, an exposure notification report and follow-up report are to be prepared and submitted as described above. If there is no reason to believe that the disease may be linked to the containment zone, then exposure is ruled out and there is no further action required.

In most cases, a disease state will include recognition of an illness, syndrome, or known disease. However, some facilities may employ medical surveillance practices that could identify a seroconversion, which may provide an additional source of information for recognition of infection or disease states.

* In most cases disease state will include recognition of an illness, syndrome, or known disease; however, some facilities may employ medical surveillance practices that could identify a seroconversion, which may provide an additional source of information for recognition of infection or disease states.

References

- Footnote 1

- Government of Canada. (2015). Canadian Biosafety Standard (2nd ed.). Ottawa, ON, Canada: Government of Canada.

- Footnote 2

- BS OHSAS 18001:2007, Occupational Health and Safety Management Systems Requirements. (2007). London, UK: British Standards Institution.

- Footnote 3

- CAN/CSA-Z1000-14 (R2014), Occupational Health and Safety Management. (2014). Mississauga, ON, Canada: Canadian Standards Association.

- Footnote 4

- CAN/CSA Z796-98 (R2013), Accident Information. (1998). Mississauga, ON, Canada: Canadian Standards Association.

- Footnote 5

- Human Pathogens and Toxins Act (S.C. 2009, c.24). (2015).

- Footnote 6

- Human Pathogens and Toxins Regulations (SOR/2015-44) (2015).

- Footnote 7

- Health of Animals Act (S.C. 1990, c. 21). (2015).

- Footnote 8

- Reportable Diseases Regulations (SOR/91-2). (2014).

- Footnote 9

- Health of Animals Regulations (C.R.C., c. 296). (2015).

Chapter 19 - Pathogen and Toxin Accountability and Inventory Control

Good biosafety and biosecurity practices include provisions to adequately account for, protect, and safeguard pathogens and toxins against loss, theft, misuse, diversion, and release. This chapter describes measures used to create an environment that protects and prevents against insider threats while simultaneously incorporating best practices of material management systems.Footnote 1 The pathogens and toxins that should be subject to accountability and control measures can be identified by the biosecurity risk assessment (i.e., the assets, as described in Chapter 6). Control measures are used to confine the assets to designated locations and to limit their access to authorized individuals using physical means (i.e., security barriers) or by operational protocols (e.g., standard operating procedures [SOPs]). Accountability measures define the oversight and the responsibility of all authorized individuals for the safekeeping of the assets. The Canadian Biosafety Standard (CBS), 2nd Edition, requires that a regulated containment zone include pathogen and toxin accountability and inventory control as part of the facility's biosecurity plan (Matrices 4.1 and 4.10 of the CBS).Footnote 2 Biosecurity, including the biosecurity risk assessment and biosecurity plan, is discussed in further detail in Chapter 6.

19.1 Pathogen and Toxin Accountability

Accountability measures aim to establish ownership of pathogens and toxins, and to describe the responsibility of each authorized individual.Footnote 3 In the context of a biosafety and biosecurity program as specified in the CBS and this volume, pathogen accountability measures can and should include any material that is known to contain a pathogen that necessitates such measures. This includes all material regulated under the Human Pathogens and Toxins Act (HPTA), Human Pathogens and Toxins Regulations (HPTR), Health of Animals Act (HAA), and Health of Animals Regulation (HAR), that contains pathogens (i.e., pure or isolated pathogen or toxin; infected or intoxicated animals, animal products or by-products, that contain an animal pathogen or part of one, or other organism that contains an animal pathogen or part of one that has been imported under an animal pathogen import permit; experimentally or otherwise intentionally infected animals or specimens collected from such animals; cell lines or cell cultures containing a pathogen or part of one that retains pathogenicity).Footnote 4Footnote 5Footnote 6Footnote 7 Nonetheless, it is generally recommended that the pathogen and toxin accountability measures of a containment zone or facility also include any additional material that is known, presumed, or suspected to be infectious but may not be subject to regulation by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA). Domestically-acquired primary specimens or cell lines that are not well-characterized and have not been assessed for the presence of pathogens should be subject to the same level of accountability and control as a sample of the isolated pathogen to demonstrate due care.

An accountability system establishes a governance structure in an organization whereby relationships between individuals are determined on an account-giving basis. In brief, accountability creates a framework where Person A is accountable to Person B and is obliged to inform Person B of his/her actions and decisions, to justify them, and to be answerable for these actions and decisions.Footnote 8 This type of relationship is present in many hierarchies and organizations, such: as a banking institution (i.e., "Person A") to a client or account holder (i.e., "Person B"); an employee to a manager; or a student to a teacher. In the context of pathogen and toxin accountability, this includes the assignment of qualified, authorized personnel to oversee the control of the pathogens, toxins, and regulated infectious material, the maintenance of accurate and timely records, and the routine verification of materials and records (i.e., auditing). These accountable authorized personnel are answerable for their actions and decisions involving pathogens, toxins, and regulated infectious material to their supervisors, the containment zone or facility directors, the licence holder or animal pathogen import permit holder, and may also be accountable to the PHAC and the CFIA.

The CBS specifies the minimum requirements for accountability and control of pathogens, toxins, and other regulated infectious material in regulated containment zones (CBS Matrix 4.10). Depending on the material in long-term storage, this can include a means to identify the pathogens and toxins (e.g., the genus, species, strain, where applicable), their risk group(s), and their locations (e.g., room, fridge/freezer, shelf). Given the transitory nature of many laboratory specimens, only those in long-term storage, which is defined as storage for greater than 30 calendar days, need to be recorded in an inventory. It is expected that materials in long-term storage are not being actively manipulated (e.g., cryopreserved or otherwise stored for reference or future use). Materials in short-term storage (less than 30 days) will normally be captured elsewhere, such as laboratory notebooks, test requests, and entry logs. Active cultures of pathogens or infectious material that require more than 30 days of incubation (e.g., continuous cell cultures) may not need to be documented in the containment zone's formal inventory, depending on the risk associated with the material, and provided that the minimum required information is documented elsewhere (e.g., daily laboratory notebook entries, cell culture logbooks), and is of sufficient detail to determine immediately if a sample is missing or has been stolen.

19.1.1 Internal Accountability System

Development and implementation of an internal accountability system in facilities where pathogens, toxins, and regulated infectious material are handled and stored is needed so that all personnel are made aware of their individual responsibilities, the administrative controls in place, and the penalties for not following this system. This may be best achieved through a policy or code of conduct describing the responsibilities of all personnel, such as the biosafety policy described in Chapter 5. This should include a description of the roles and responsibilities of authorized personnel, senior management, the institutional biosafety committee, and the biological safety officer (BSO), so that all personnel are made aware of their legal responsibilities and institutional expectations, as well as those of their co-workers. In licensed facilities authorized to conduct controlled activities with human pathogens and toxins, the licence holder is identified as the individual with the ultimate legal accountability under the HPTA and HPTR. In facilities that have imported an animal pathogen, the importer is identified as the individual with the ultimate legal accountability under the HAA. The disciplinary actions (i.e., penalties or punishments) for non-compliance with the internal accountability system should be clearly documented and communicated to all personnel.

When developing pathogen and toxin accountability procedures and tools, it is important to consider the material that is present within the containment zone and the associated biosafety and biosecurity risks. This is best determined in consultation with the facility's BSO. The level of accountability and control will be determined by the risk associated with the material. For example, maintaining information on the storage and use of biological material in laboratory notebooks may be suitable for low risk biological material and toxins (e.g., Risk Group 1 [RG1]); whereas, high risk pathogens (e.g., Risk Group 3 [RG3] or Risk Group 4 [RG4]) will necessitate detailed inventories of pathogens and toxins in storage, detailed records of transfers to other zones or facilities, documented access and authorization protocols, and regular verification of material and records (i.e., checks and audits). It is also encouraged that institutional pathogen and toxin accountability procedures and tools address accountability concerns that may arise in the event that the licence holder or animal pathogen import permit holder terminates their affiliation with the institution (e.g., change of employer, retirement) to ensure that the transfer or disposal of all regulated material is carried out in accordance with all legal requirements.

19.1.2 Accountability Measures during Movement and Transportation

The movement and transportation of biological material is a routine procedure in laboratories and other containment zones. Good microbiological laboratory practices will likely prevent contamination and inadvertent spills; nonetheless, accounting and control provisions for the movement or transportation of pathogens and toxins throughout their journey are important factors to reduce the risk of loss or theft by insider or outsider threats. For this reason, the biosecurity plan should include provisions and policies for transfer management outlining biosecurity-specific procedures for the shipping, receiving, monitoring, and storage of packages that contain pathogens, toxins, and other regulated infectious material. For example, a documented contingency plan for the receipt and security for unexpected shipments (i.e., parcels of pathogens or toxins that arrive at a facility that had not been requested nor arranged) should be considered. In addition, licensed facilities are required to notify the PHAC in the event that the facility has come into possession of a human pathogen or toxin that has not been authorized by the licence (HPTA 12[2]), when an expected shipment of a human pathogen or toxin is missing and has not been received (HPTA 14), or when a shipment of a security sensitive biological agent (SSBA) has not been received within 24 hours of when it was expected (HPTR 9[1][c][iii]). Established written provisions or procedures on how to handle such events will allow the licence holder to track and gain control of the shipment quickly and secure it in an appropriate licensed area without delay. In addition, where a licensed facility is authorized for activities involving SSBAs, all employees in the shipping and receiving areas are required to have a valid Human Pathogens and Toxins Act Security Clearance (HPTA Security Clearance) issued by the PHAC if they pack or unpack shipments in the shipping and receiving area or if they plan to temporarily store SSBAs (HPTA 33, HPTR 28). Licensed facilities that conduct transfers of human pathogens and toxins under the same licence should include in their biosecurity plan a description of how these transfers will take place, including chain-of-custody documents and provisions for safeguarding the agents against theft, loss, or release. Further information on movement and transportation of infectious material and toxins is discussed in Chapter 20; information on regulatory oversight of pathogens, toxins, and other regulated infectious material, including transfers, is discussed in Chapter 23.

19.2 Inventories and Inventory Control Systems

An inventory is a list of biological assets in possession of a facility, and includes the identification of the pathogens and toxins in long-term storage both inside and outside of the containment zone. Inventories are key records in areas where activities with human and animal pathogens and toxins are conducted that allow authorized personnel who are accountable for the control of this material to prevent it from being misused, misplaced, stolen, or released. Additionally, inventories allow individuals working with human and animal pathogens and toxins to be aware of the nature and scope of the material present so that appropriate precautions are used to prevent personnel exposure or release. An inventory control system is a process to manage and locate materials in the facility or containment zone. They are common to any quality assurance program and are required in quality management systems, including the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) standard ISO 9001, ISO 15189, National Standard of Canada (CAN)/ Canadian Standards Association (CSA) standard CAN/CSA Z15190, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Principles of Good Laboratory Practice, and the European Committee for Standardization (CEN) Laboratory Biorisk Management Standard.Footnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 11Footnote 12Footnote 13

19.2.1 Inventory Elements

The minimum inventory requirements for pathogens and toxins in long-term storage in regulated containment zones are specified in Matrix 4.10 of the CBS. A description of the inventory control system is also required as part of the biosecurity plan (CBS Matrix 4.1). The level of detail of the information to capture in the inventory records and the complexity of the inventory control system will vary depending on the risks associated with the pathogens or toxins and the needs of the facility or containment zone. At minimum, the inventory of pathogens, toxins, and other regulated infectious material in long term storage must include (CBS Matrix 4.10):

- a description of the pathogen or toxin, in sufficient detail to identify the level of risk of the material, including:

- the pathogen or toxin name (e.g., genus, species, name of toxin); and

- risk group(s);

- storage location (e.g., room, freezer); and

- any pathogens, toxins, or other regulated infectious material stored outside of the containment zone (for CL2 and containment level 3 [CL3] only).

- For RG3, and RG4 pathogens, and SSBA toxins only, the inventory must also include:

- the specific identification of the pathogens, toxins, and other regulated material (e.g., genus, species, strain, subtype, batch number); and

- a means to allow for the detection of a missing or stolen sample in a timely manner (e.g., include quantity information, such as number of vials or, for SSBA toxins, amount by weight [in mg or µg] for stocks in storage).

It may be advantageous for any facility to establish an inventory system in order to document and manage this information in a consistent manner, or the required information may be integrated into an existing inventory or inventory system. Additional information can be captured to create a more useful and robust inventory system. What additional information can be included depends on the facility's activities and needs. For example, compliance with quality management standards such as ISO 9001 or ISO 15189 may require documentation of additional or different information. The following is a list of additional elements that may be considered to create a comprehensive and robust inventory system of pathogens and toxins in any containment zone:

- additional information of the pathogen or toxin, such as:

- strain or subtype; and

- parental organism of toxin;

- an indication of the pathogenicity of the strain (e.g., attenuated vaccine strain, highly pathogenic strain, drug resistant variant), where appropriate;

- vial or sample identification (e.g., tube number, batch number, barcode number), where appropriate;

- form of the materials (e.g., lyophilized, suspension, concentrate, pellet, stab culture);

- number of vials, quantity (e.g., concentration, volume) contained in the vials, where appropriate or relevant;

- precise storage location (e.g., freezer, shelf, rack, box);

- location(s) of use;

- name and contact information of the responsible person;

- special characteristics (e.g., restrictions of use noted on a licence or animal pathogen import permit);

- manufacturer's name or source;

- dates of receipt, acquisition, or generation of the material;

- dates of removal, use, transfer, inactivation, or disposal;

- expiry date (e.g., lyophilized cultures);

- reference to associated documentation, such as:

- import authorizations (i.e., licence and animal pathogen import permits) and transfer letters;

- approved method of decontamination or inactivation;

- Pathogen Safety Data Sheets (PSDSs); and

- where the inventory includes SSBAs:

- list of authorized individuals who have access;

- list of individuals with a valid HPTA Security Clearance.

19.2.2 Inventory Review and Updates

In order to be useful, inventories need to be updated regularly; it is difficult to determine if a sample is missing if the inventory does not accurately reflect the material in possession at the time. Inventories should be updated annually and whenever a sample is used, transferred, inactivated, or disposed of, and whenever new material is identified as the result of diagnostic testing, receipt, generation, or production. Institutions are encouraged to develop internal policies outlining timeframes for regular and scheduled inventory reviews to compare material in storage with the inventory list and to update accordingly. For routine inventory checks, verifying a representative subset of the material may be a suitable approach.

19.2.3 Inventory Control Systems and Reporting

Inventories of pathogens, toxins, and other regulated infectious material in long-term storage should be readily available and easily searchable, whether an electronic or a paper system is used. Inventory control systems, such as record books, inventory software, or database systems, can be used to manage inventories of pathogens and toxins.Footnote 14 A notification process (i.e., internal and external reporting) should be in place for identifying, reporting, and remediating any problems, including inventory discrepancy, storage equipment failure, security breaches, or disposal or release of materials. For security and storage considerations, it is encouraged that facilities minimize the quantities of pathogens and toxins that comprise the inventory, whenever possible.

Licensed facilities are not required to submit regular reports of their inventories to the PHAC; however, it is expected that they are able to describe their record-keeping system(s) upon request (e.g., How would you find sample "X" in your facility? Do you have pathogen "Y" in your inventory?). In addition, licence holders are required to notify the PHAC without delay if they inadvertently produce or come into possession of a human pathogen or toxin that they are not authorized to possess (HPTA 12[2]) or have reason to believe that a human pathogen that was in their possession has been stolen or is otherwise missing (HPTA 14).

19.3 Storage and Labelling

Controls should be implemented to limit access to pathogens and toxins stored within a facility to authorized personnel for their specified purpose. Security barriers may include locks, security storage equipment, tamper-evident storage containers, locked storage compartments inside cabinets or refrigerators, or storage areas located inside restricted access areas. Whenever possible, pathogens and toxins should be stored inside the containment zone where they are handled, or in a zone at the same containment level. RG2 and RG3 pathogens and toxins may be stored outside of the containment zone, provided that additional security measures are implemented (CBS Matrix 4.6). Samples being banked or stored for long periods of time should be appropriately labelled (i.e., clearly and permanently) and meet the current requirements of the Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System (WHMIS).Footnote 15

References

- Footnote 1

- Salerno, R. M., & Gaudioso, J. (2007). Laboratory Biosecurity Handbook. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press.

- Footnote 2

- Government of Canada. (2015). Canadian Biosafety Standard (2nd ed.). Ottawa, ON, Canada: Government of Canada.

- Footnote 3

- AccountAbility. (2008). AA1000 Accountability Principles Standard 2008. Washington, DC, USA: AccountAbility North America.

- Footnote 4

- Human Pathogens and Toxins Act (S.C. 2009, c. 24). (2015).

- Footnote 5

- Human Pathogens and Toxins Regulations (SOR/2015-44). (2015).

- Footnote 6

- Health of Animals Act (S.C. 1990, c. 21). (2015).

- Footnote 7

- Health of Animals Regulations (C.R.C., c. 296). (2015).

- Footnote 8

- Schedler, A. (1999). Conceptualizing Accountability. In: Schedler, A., Diamond, L., & Plattner, M. F. The Self-Restraining State: Power and Accountability in New Democracies (pp. 13-28). London, UK: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

- Footnote 9

- International Organization for Standardization. (2015). ISO 9000 Resources: ISO 9001 Inventory Control Summary. Retrieved 11/03, 2015, from http://www.iso9000resources.com/ba/inventory-control-introduction.cfm

- Footnote 10

- ISO 15189:2012, Medical Laboratories - Requirements for Quality and Competence. (2012). Geneva, Switzerland: International Organization for Standardization.

- Footnote 11

- CAN/CSA-Z15190-05. (R2010) , Medical Laboratories - Requirements for Safety. (2010). Mississauga, ON, Canada: Canadian Standards Association.

- Footnote 12

- ENV//MC/CHEM(98)17. (1998). OECD Series on Principles of Good Laboratory Practice and Compliance Monitoring, Number 1: OECD Principles in Good Laboratory Practice (as revised in 1997). Environment Directorate, Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, Paris, France.

- Footnote 13

- CEN Workshop 31 - Laboratory biosafety and biosecurity. CEN Workshop Agreement (CWA) 15793:2011, Laboratory Biorisk Management Standard. (2011). Brussels, Belgium: European Committee for Standardization.

- Footnote 14

- Perkel, JM. (2015). Toolbox - Lab-inventory management: Time to Take Stock. Nature. 524:125-126

- Footnote 15

- Health Canada. (2015). Workplace Hazardous Materials Information System (WHMIS). Retrieved 11/03, 2015 from http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/ewh-semt/occup-travail/whmis-simdut/index-eng.php

Chapter 20 - Movement and Transportation of Infectious Material or Toxins

The movement and transportation of infectious material and toxins (or biological material suspected of containing them) is an essential part of routine laboratory procedures in both research and diagnostic settings. For the purposes of this chapter, a distinction is made between movement and transportation, with movement denoting the action of moving material within a containment zone or building, and transportation denoting the action of transporting material to another building or location, within Canada or abroad. This distinction is required because the transportation of infectious substances falls under the Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act (TDGA), Transportation of Dangerous Goods Regulations (TDGR), and Dangerous Goods Regulations (DGR) issued by the International Air Transport Association (IATA), and is discussed separately.Footnote 1 Footnote 2 Footnote 3 This chapter also provides information pertaining to the regulatory requirements for the transfer, importation, and exportation of pathogens and toxins.

20.1 Movement of Infectious Material or Toxins