Archived - Introducing the National Advisory Committee on Infection Prevention and Control

Download this article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDFPublished by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 44-11: Healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial resistance

Date published: November 1, 2018

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 44-11, November 1, 2018: Healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial resistance

News from the agency

The National Advisory Committee on Infection Prevention and Control (NAC-IPC)

T Ogunremi1, K Dunn1, L Johnston2, J Embree3, on behalf of the National Advisory Committee on Infection Prevention and Control (NAC-IPC)

Affiliations

1 Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, ON

2 Dalhousie University, Halifax, NS

3 University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB

Correspondence

Suggested citation

Ogunremi T, Dunn K, Johnston L, Embree J on behalf of the National Advisory Committee on Infection Prevention and Control. The National Advisory Committee on Infection Prevention and Control (NAC-IPC). Can Commun Dis Rep 2018;44(11):283-9. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v44i11a03

Keywords: Infection prevention and control, advisory committee, evidence-based guidelines, healthcare-associated infections, infectious disease

Note

Committee members are noted at the end of the paper

Abstract

This paper describes the work of the National Advisory Committee on Infection Prevention and Control (NAC-IPC), a longstanding external advisory body that provides subject matter expertise and advice to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) on the prevention and control of infectious diseases in Canadian health care settings. Originally established by Health Canada as the Infection Control Guidelines Steering Committee in 1992, this advisory board has been providing expert advice on infection prevention and control (IPC) guideline development for over 25 years.

The NAC-IPC provides advice to inform the development of comprehensive or concise guidelines, quick reference guides and interim guidelines (usually for emerging pathogens), working closely with PHAC’s national Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAIs) surveillance programs for Canadian health care facilities. PHAC’s HAI-IPC professionals conduct the necessary literature research, data extraction, evidence synthesis, evidence grading (where applicable) and scientific writing for the guidelines. Due to the paucity of clinical trials and high quality observational studies to inform recommendations for emerging pathogens, expert opinion is critical for interpreting available evidence.

Introduction

Global infectious disease threats call for international knowledge exchange and a national coordinated response. Since its inception in 2004, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) has provided national leadership in response to public health threats using an evidence-based approach that employs scientific excellence and relevant expert advice from external advisory bodies. These external advisory bodies provide PHAC with the means to involve individuals outside of government, who have valuable knowledge and expertise in the Agency’s national guideline development process.

External advisory bodies are established to assist PHAC in developing guidance on specific medical, scientific, technical, policy or program matters within the scope of the Agency’s mandate Footnote 1. Well‑known external advisory bodies to PHAC include the National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) and the Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine (CATMAT) Footnote 2Footnote 3. This article describes the work of the National Advisory Committee on Infection Prevention and Control (NAC-IPC).

Background

Health Canada established the original Infection Control Guidelines Steering Committee in 1992. This committee played a key role during the SARS outbreak in 2003, and began reporting to PHAC following the creation of the Agency in 2004. Its name was changed to the Infection Prevention and Control Expert Working Group in 2011. Earlier in 2018, the decision was made to transition this expert working group to an external advisory body. This transition resulted in the name change to NAC-IPC and a change in the reporting structure. Previously reporting to PHAC through the Program Director, the NAC-IPC now reports to the Vice President of the Infectious Disease Prevention and Control Branch. The Committee’s mandate and function remain the same.

The transition of NAC-IPC from an expert working group to an external advisory body complies with PHAC’s policy and directive for such committees Footnote 1. The resulting change in the committee reporting structure will strengthen the NAC-IPC’s links with provincial and territorial partners through the Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health. Such links are particularly valuable during an emergency event, where the timely uptake of newly released Healthcare-Associated Infection-Infection Prevention and Control (HAI-IPC) guidelines and statements is critical. Examples of such work in the past include the provision of timely public health, scientific and clinical advice to PHAC during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic and the 2013–2016 Ebola virus international public health emergency.

The objective of this article is to describe the mandate and membership of the NAC-IPC; identify how the NAC-IPC coordinates with other PHAC programs; give an overview of the guideline development process; and provide a list of current PHAC guidelines developed with expert advice from NAC-IPC.

Mandate and membership

The mandate of NAC-IPC is to support PHAC in promoting public health; preventing and controlling infectious diseases; preparing for and responding to public health emergencies; serving as a central point for sharing Canada’s expertise; applying international research and development to national public health programs; strengthening intergovernmental collaboration on public health; and facilitating national approaches to public health policy and planning—all as it relates to healthcare-associated infections.

To guide these activities, NAC-IPC provides expert advice to PHAC’s Healthcare-Associated Infection‑Infection Prevention and Control (HAI-IPC) program for:

- developing national evidence-based IPC guidelines for health care settings Footnote 4

- providing technical and scientific advice to PHAC in response to emerging and re-emerging pathogens and infectious disease public health threats

- developing strategies to prevent and control HAIs, antimicrobial resistance (AMR) and other related public health events in settings where health care services are delivered in Canada; and

- identifying priorities for HAI and IPC research

The NAC-IPC consists of up to 15 members who are recruited through a transparent targeted nomination process. Their number may be adjusted to ensure the appropriate range of expertise, experience and geographic representation. The Committee also includes non-voting liaison members who act as representatives of provinces and territories, associations and industries and express opinions on behalf of their organization. Liaison members support the NAC-IPC by providing additional knowledge and expertise; sharing relevant updates from their respective organizations; and reviewing and providing feedback on NAC-IPC statements and guidance documents.

A call for interested applicants or nominations for NAC-IPC membership is sent to relevant professional associations for circulation to their community of practice. Selection of committee members involves a range of criteria including leadership, geographical representation, advanced knowledge and certification in identified fields of practice, with specialized expertise suited to guideline development and response to emerging HAI issues.

The Committee is currently composed of members with expertise in infectious diseases, medical microbiology, infection prevention and control, public health, health care epidemiology and occupational health and/or hygiene. Task groups, led by a member of NAC-IPC and consisting of both NAC-IPC and non‑NAC‑IPC members with relevant subject matter expertise, are appointed to lead the development of each guideline or product. The task groups report to NAC-IPC during the product development phase and the approval process prior to release.

Interconnectedness with other PHAC programs and products

The HAI-IPC program works closely with other PHAC programs that have related interests or mandates. This includes the Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program (CNISP), which is responsible for national surveillance (rates and trends) of HAIs, including emerging pathogens in Canadian health care facilities; and the Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System (CARSS), which is responsible for the national surveillance of AMR and antimicrobial use Footnote 5Footnote 6. The work of these and other inter-related programs inform the work undertaken by the HAI-IPC program (e.g. revisions to an existing guidance document on carbapenem–resistant gram-negative bacilli in health care settings and other AMR-IPC products). These AMR–related products will contribute to PHAC’s national leadership on this issue while ensuring consistency and congruency of published PHAC products on HAIs and AMR.

Guideline development process

Guideline development is a resource-intensive, long term effort that necessitates ongoing prioritization and collaboration to maximize available resources. Prioritization is based on the urgency of a proposed guideline topic or issue; the scope of the issue; a public health threat or impact (especially for novel, emerging or re-emerging pathogens); PHAC and Government of Canada priorities; provincial/territorial requests or identified needs for a national perspective to facilitate a coordinated approach; and identified gaps and availability of suitable international guidance. As a group, NAC-IPC members and liaison members offer their assessment of relevant published guidelines, provide information on relevant documents under development by other organizations and identify opportunities for collaborations.

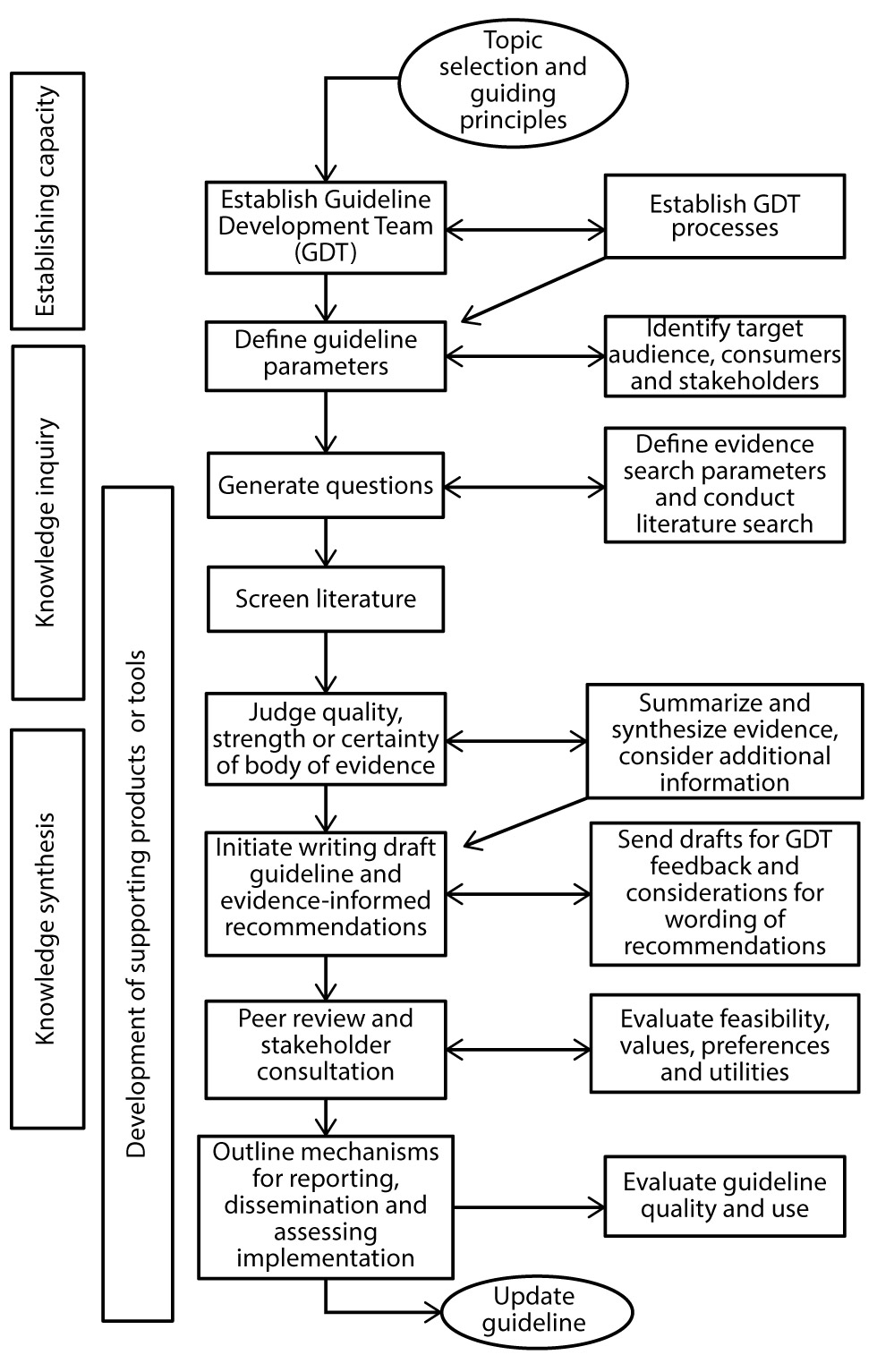

HAI-IPC program staff function as project leads responsible for guideline development activities. These include conducting the literature research, data extraction, evidence synthesis, critical appraisal of the evidence, drafting the evidence-based guidelines and related documents, and providing secretariat support to NAC-IPC. The guidelines developed generally fall into one of four categories with varying complexity and scope: comprehensive guidelines, concise guidelines, quick reference guides and interim guidelines (usually for emerging pathogens). The development of the more comprehensive guidelines is generally done by researching peer-reviewed and grey scientific literature using a systematic review process (see Figure 1). Other documents developed may be informed by a narrative literature review or environmental scan with targeted literature search. Each guideline or document includes a description of the methods and/or approach used for its development. Following public release of the guidelines, the HAI-IPC program works with NAC-IPC to review relevant new evidence and update the guidelines when indicated.

Figure 1: Guideline Development Process for PHAC’s national HAI-IPC guidelines

Text description: Figure 1

Figure 1: Guideline Development Process for PHAC’s national HAI-IPC guidelines

This is a flow chart indicating the various steps in developing a comprehensive guideline.

- First step is the guideline topic selection and identifying the guiding principles for this;

- Second step is to establish a Guideline Development Team (GDT) as well as establishing the GDT Processes;

- Third step is to define the guideline parameters and then identify target audience, consumers and stakeholders;

- The fourth step is to generate questions, followed by defining evidence search parameters and conducting a literature search;

- The fifth step is to screen the literature;

- The sixth steps is to judge the quality, strength or certainty of the body of evidence; summarize and synthesize the evidence, and consider any relevant additional information;

- The seventh step is to initiate writing the draft guideline and developing evidence-informed recommendations. This involves sending the draft for GDT feedback and considerations for wording of recommendations;

- The eight step is to have the guideline peer reviewed and conduct stakeholder consultations. This also involves evaluating feasibility, values, preferences and utilities;

- The ninth step is to outline mechanisms for reporting, dissemination and assessing implementation, and to evaluate the guideline quality and use;

- The final step is to update the guideline.

The various steps in the guideline development process can be categorized into one or more phases: establishing capacity, knowledge inquiry, knowledge synthesis and development of supporting products and tools.

Grading of evidence

The development of guidelines involves extracting relevant data from the literature review, synthesizing the literature, interpreting the evidence and grading available evidence (where relevant). Some guidelines are mostly descriptive and informed by expert opinion due to the absence of published evidence. The criteria used for grading evidence that informs the national evidence-based IPC guideline series are outlined in Table 1.

| Strength of evidence | Grades | Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Strong | AI | Direct evidence from meta-analysis or multiple strong design studies of high quality, with consistency of results |

| AII | Direct evidence from multiple strong design studies of medium quality with consistency of results OR At least one strong design study with support from multiple moderate design studies of high quality, with consistency of results OR At least one strong design study of medium quality with support from extrapolation from multiple strong design studies of high quality, with consistency of results |

|

| Moderate | BI | Direct evidence from multiple moderate design studies of high quality, with consistency of results OR Extrapolation from multiple strong design studies of high quality, with consistency of results |

| BII | Direct evidence from any combination of strong or moderate design studies of high/medium quality, with a clear trend but some inconsistency of results OR Extrapolation from multiple strong design studies of medium quality or moderate design studies of high/medium quality, with consistency of results OR One strong design study with support from multiple weak design studies of high/medium quality, with consistency of results |

|

| Weak | CI | Direct evidence from multiple weak design studies of high/medium quality, with consistency of results OR Extrapolation from any combination of strong/moderate design studies of high/medium quality, with inconsistency of results |

| CII | Studies of low quality regardless of study design OR Contradictory results regardless of study design OR Case series/case reports OR Expert opinion |

|

Developing recommendations and providing expert opinion

Where possible, recommendations are informed by evidence from summary tables developed as part of the systematic or narrative literature review. For ethical and feasibility reasons, clinical trials for common infection prevention and control issues are almost non-existent, observational studies are limited and descriptive studies do not provide evidence on causal association. As a result, expert opinion is a necessary part of the HAI-IPC guideline development process. Expert opinion is also essential during the early phases of an epidemic brought on by a newly emerging pathogen, as peer-reviewed publications are often limited under these circumstances.

Recommendations for public health practice are also informed by health care epidemiology, monitoring and analysis of IPC issues and trends, as well as feedback from stakeholder and provincial/territorial partners. Advice provided by NAC-IPC complements provincial/territorial efforts and considers all relevant federal, provincial, territorial and local legislation, regulations and policies. Table 2 lists the guidelines and other published documents developed by the HAI-IPC program with advice from or involvement of NAC-IPC member(s) Footnote 1.

Conclusion

The NAC-IPC is an external advisory body that continues the work done under previous names for the past 25 years providing expert advice on the development of national HAI-IPC guidelines. The rigour and methodology used to develop these guidelines continues to improve, as do the opportunities for international collaboration and knowledge exchange and mobilization.

The NACI-IPC is committed to strengthening linkages with other PHAC programs and external partners, and informing the wider federal-provincial-territorial public health network on HAI-IPC issues. This is important not only for current matters, but also for emerging public health threats that can potentially impact Canadian health care settings. In such a case, the NAC-IPC will be able to provide expert interpretation of available evidence on emerging pathogens and, as needed, the rapid development of relevant evidence-based IPC guidelines.

Authors’ statement

TO – Conceptualization, methodology, writing of original draft, review and editing

KD – Conceptualization, supervision, writing, review and editing

LJ – Conceptualization, writing, review and editing

JE – Conceptualization, writing, review and editing

Conflict of interest

None.

Contributors

The authors would like to acknowledge the tireless contributions of all NAC-IPC members—past and present—and their commitment to the prevention and control of infectious disease in Canada:

NAC-IPC members: Joanne Embree (Chair), Kathleen Dunn (Executive Secretariat), Molly Blake, Gwen Cerkowniak, Maureen Cividino, Nan Cleator, Della Gregoraschuk, Bonnie Henry, Jennie Johnstone, Matthew Muller, Heidi Pitfield, Patsy Rawding, Patrice Savard, Stephanie Smith, Jane Stafford

Past Committee Members: Lynn Johnston (Past Chair and Member, 1996–2016), Lindsay Nicolle (Past Chair and Member, 1992–2006), Kathleen Dunn (Past Co-Chair), Sandra Boivin, Julie Carbonneau, John Conly, Brenda Dyck, John Embil, Karin Fluet, Charles Frenette, Colleen Hawes, Agnes Honish, Linda Kingsbury, Dany Larivée, Mary Leblanc, Anne Matlow, Catherine Mindorff, Dorothy Moore, Donna Moralejo, Deborah Norton, Shirley Paton, Diane Phippen, Pierre St. Antoine, Filomena Pietrangelo, Sandra Savery, JoAnne Seglie, Paul Sockett, Geoffrey Taylor, Mary Vearncombe, Cathie Walker, Dick Zoutman

Liaison Member Organizations: Accreditation Canada (AC), Association des infirmières en prévention des infections (AIPI), Association des médecins microbiologistes infectiologues du Québec (AMMIQ), Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada (AMMI-Canada), Canadian Association of Medical Device Reprocessing (CAMDR), Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI), Canadian Medical Association (CMA), Canadian Nurses Association (CNA), Canadian Occupational Health Nurses Association (COHNA), Canadian Patient Safety Institute (CPSI), Canadian Standards Association (CSA), HealthCareCAN, Infection Prevention and Control - Canada (IPAC), Victorian Order of Nurses Canada (VON Canada), Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC)

PHAC HAI-IPC Program (past and present): Kathy Dunn (Manager), Andrea Coady, Frédéric Bergeron, Katherine Defalco, Caroline Desjardins, Jennifer Kruse, Fanie Lalonde, Toju Ogunremi, Laurie O’Neil, Adina Popalyar, Christine Weir

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Caroline Desjardins for formatting the tables, figure and references, and Hayley Watt for compiling the list of past and present NAC-IPC members. The authors will also like to thank Andrea Coady, Margaret Bodie, Katherine Defalco and Adina Popalyar for reviewing the final manuscript.

Funding

The National Advisory Committee on Immunization Prevention Control is supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada.