The Federal Workplace Mental Health Checklist

2019 Results for the Federal Public Service

On this page

- Executive Summary

- Introduction

- Background – The 2017 Checklist

- Methodology – The 2019 Checklist

- Focus Area 1 – Leadership and Governance

- Focus Area 2 – Awareness and Training

- Focus Area 3 – Mental Health Support Services

- Focus Area 4 – Data, Reporting and Continuous Improvement

- Areas Requiring Support

- The Centre of Expertise for Mental Health in the Workplace

- Conclusion

- Annex 1 – Results Tables

- Annex 2 – List of Participating Organizations

- Endnotes

The Federal Workplace Mental Health Checklist – 2019 Results

(PDF, 794 KB)

Infographic: Highlights from the 2019 Federal Workplace Mental Health Checklist

(PDF, 691 KB)

Executive Summary

The Centre of Expertise on Mental Health in the Workplace (the Centre) launched the second iteration of the Federal Workplace Mental Health Checklist (the Checklist) in summer 2019. The Checklist has two objectives: to better understand 1) how organizations are implementing the Federal Public Service Workplace Mental Health Strategy (the Strategy) and 2) how organizational activities are aligning to the National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace (the Standard). It does so by gathering feedback from the Core Public Administration and Separate Agencies. The results of the Checklist are then used by the Centre to inform planning of enterprise-wide efforts.

The 2019 Checklist was fielded from July 29 to September 13, 2019, and included 17 questions under four focus areas. Sixty-seven organizationsFootnote 1 (31 small organizations and 36 large organizationsFootnote 2) completed the 2019 Checklist, for a total response rate of 77%. Fifty-one organizations completed both the 2017 and 2019 iterations.

Key Findings

The Checklist assessed progress in four focus areas:

| Focus Area | Results |

|---|---|

| Leadership and Governance |

|

| Awareness and Training |

|

| Mental Health Support Services |

|

| Data, Reporting and Continuous Improvement |

|

The 2019 Checklist asked organizations to identify areas that require further support. The most commonly identified areas were:

- conducting a psychological hazard analysis and aligning with the Standard

- resourcing to implement the Strategy and align to the Standard

- building capacity for enhanced data and business intelligence

Alignment with the Standard

Organizations are making some progress in aligning with the Standard, as laid out in the third Technical Committee Report “Building Success: A Guide to Establishing and Maintaining a Psychological Health and Safety Management System in the Federal Public Service” (the Third Report). Progress can be assessed by looking at both the Checklist and Management Accountability Framework (MAF) results:

- 100% of small organizations and 94% of large organizations have appointed a Mental Health Champion (the 2017 Checklist)

- 81% of small organizations and 81% of large organizations have appointed a project sponsor (the 2019 Checklist)

- 84% of small organizations and 88% of large organizations have included awareness about mental health into their strategic communications plan (the 2017 Checklist)

- 35% of small organizations and 48% of large organizations have performed a psychological hazard analysis informed by MAF results (MAF 2017-2018)

- 70% of small organizations and 84% of large organizations have reviewed workplace programs and policies from a mental health lens (MAF 2017-2018)

Opportunities for Growth

The results of the 2019 Checklist identify that, while progress is being made, opportunities for growth remain, including:

- ensuring adequate resources are available to support Mental Health Action Plans, as required by the Strategy

- enhancing support services such as disability and case management systems, ombuds-type resources and peer support initiatives

- ensuring those leading mental health efforts have adequate training, specifically in hazard identification and in establishing a Psychological Health and Safety Management System

- identifying and securing sources of data to enhance the understanding of the psychological health in organizations

Moving Forward

Workplace mental health is a top priority for the Federal Public Service. A psychologically healthy and safe workplace is the foundation of an effective, productive and engaged workforce. While organizations are making progress on implementing the Strategy and aligning with the Standard, there is still work to do. The Centre of Expertise on Mental Health in the Workplace will continue to support organizations in making advancements in addressing mental health in the workplace by:

- providing direct support and guidance to organizations implementing action plans to address mental health and/or align with the Standard

- building capacity and connection through networks and communities of practice

- strengthening data and business intelligence

- providing access to credible leading practices, resources and tools

- raising awareness of mental health problems and illnesses

As diversity, harassment, violence and inclusion intersect with mental health and play an important part in aligning with the Standard,Footnote 3 the Centre will consider the intersections of these factors as it works toward an integrated agenda to achieve workplace wellness.

Introduction

In any given week, 500,000 Canadians are unable to come to work due to mental health problems or illnesses.Footnote 4 In January 2013, the Mental Health Commission of Canada (MHCC) launched the National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace (the Standard) because they believe that “Ensuring good psychological health and safety in the workplace is vitally important for all Canadians.”Footnote 5 The Standard is a set of voluntary guidelines, tools and resources intended to guide organizations to establish and maintain a psychologically healthy and safe workplace.Footnote 6 At the heart of the Standard is the Psychological Health and Safety Management System (PHSMS), a systematic approach to assessing how policies, processes and interactions in the workplace might impact the psychological health and safety of employees.Footnote 7

A Psychologically healthy and safe workplace is a workplace that:

- actively works to prevent harm to workers’ psychological health including in negligent, reckless, or intentional ways

- promotes workers’ psychological well-being

- The Standard

In March 2015, the Clerk of the Privy Council placed mental health at the top of the agenda for the Federal Public ServiceFootnote 8 and established the Clerk’s Contact Group on Mental Health. The same month, the Government of Canada and the Public Service Alliance of Canada established the Joint Task Force (JTF) on Mental Health. Between September 2015 and January 2018, the JTF on Mental Health released three reports, with a focus on continuous improvement and the successful implementation of measures to improve mental health in the workplace.Footnote 9

The Federal Public Service Workplace Mental Health Strategy (the Strategy) was released in June 2016. The Strategy moves forward the work of the JTF on Mental Health and that of the Clerk’s Contact Group on Mental Health. The Strategy is an important step in the Government of Canada’s efforts to build a healthy, respectful and supportive work environment. As part of the Strategy, federal organizations are required to develop action plans for achieving the organization-specific objectives under three strategic goals:

- changing the culture to be respectful to the mental health of all colleagues

- building capacity with tools and resources for employees at all levels

- measuring and reporting on actions

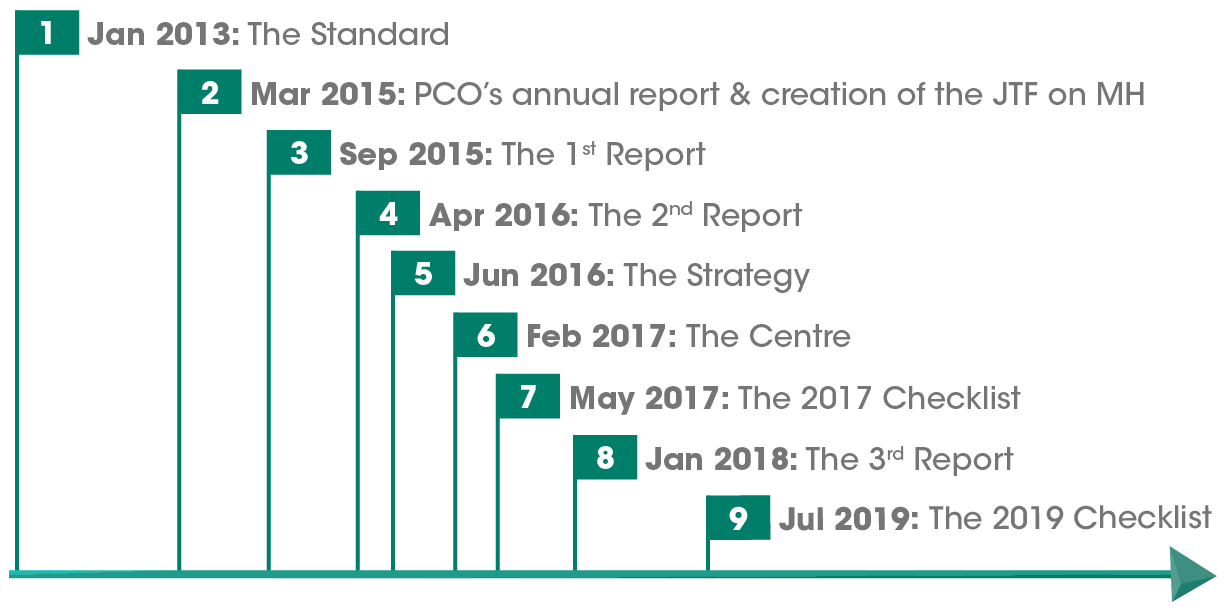

Figure 1: How the vision, the Strategy, the Standard and the Joint Task force for Mental Health Technical Committee Third Report work together to advance psychological health and safety in the Federal Public Service.

Bringing the Pieces Together

What we are working to achieve

The Vision

We will strive to create a culture that enshrines psychological health, safety and well-being in all aspects of the workplace through collaboration, inclusivity and respect; this obligation belongs to every individual in the workplace.

Where we need to focus, to achieve our Vision

The Strategy

The Federal Public Service Workplace Mental Health Strategy (the Strategy) focuses on three strategic goals for achieving the Vision:

- change the culture,

- build capacity, and

- measure, report and continuously improve.

A tool that can support organizations in implementing the Strategy

The Standard

The National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace (the Standard) is a set of voluntary guidelines, tools and resources to help organizations establish and maintain a psychologically healthy and safe workplace.

At the heart of the Standard is the Psychological Health and Safety Management System (PHSMS), a systematic approach to assessing how policies, processes and interactions in the workplace might impact employee mental health and well-being.

A guide to operationalizing the Standard in the context of the Federal Public Service

The Joint Task Force for Mental Health Technical Committee’s Third Report

The third report, “Building Success,” is a guide to establishing and maintaining a PHSMS in the Federal Public Service.

In February 2017, the Centre of Expertise on Mental Health in the Workplace (the Centre) was established to provide support, expertise and leadership to address psychological health and safety in Canada’s Federal Public Service. As part of its mandate, the Centre supports federal organizations to achieve the organization-specific objectives laid out in the Strategy, and to align with the Standard.

The Centre developed the Federal Workplace Mental Health Checklist (the Checklist) to assess the implementation of the Strategy and alignment with the Standard across the Government. The Checklist also informs the Centre’s planning of enterprise-wide efforts. The first Checklist was fielded in spring 2017, with a revised iteration of the Checklist was fielded in summer 2019. The 2019 Checklist questions, along with a summary of results, can be found in Annex 1.

- In January 2013, the National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace (the Standard) was launched

- In March 2015, the Clerk of the Privy Council placed mental health at the top of the agenda for the Federal Public Service and The Joint Task Force (JTF) on Mental Health was established

- In September 2015, the JTF on Mental Health published their first report

- In April 2016, the JTF on Mental Health published their second report

- In June 2016, the Federal Public Service Workplace Mental Health Strategy (the Strategy) was released

- In February 2017, the Treasury Board launched the Centre of Expertise on Mental Health in the Workplace (the Centre)

- In May 2017, the Centre fielded the pilot of the Federal Workplace Mental Health Checklist (the Checklist)

- In January 2018, the JTF on Mental Health published a guide to establishing and maintaining a Psychological Health and Safety Management System (PHSMS) in the Federal Public Service, also referred to as third report

- In July 2019, the Centre fielded the 2019 Checklist

Background – The 2017 Checklist

The first iteration of the Checklist was developed in 2017 as an organizational self-assessment tool. Organizations were encouraged to engage internal stakeholders to develop their responses. The content included 13 questions under four focus areas that align with the goals of the Strategy:

| Focus Areas Covered by the Checklist | Goals of the Strategy |

|---|---|

| Leadership and Governance | Change the culture |

| Awareness and Training | Change the culture and build capacity |

| Mental Health Support Services | Build capacity |

| Data, Reporting and Continuous Improvement | Measure, report and continuously improve |

The 2017 Checklist was fielded from May 31 to June 6, 2017, and was completed by 67 organizations. The results were made available in fall 2017, and the key findings were as follows:

- Organizations had structures in place to support improvements to mental health in the workplace.

- Training and awareness sessions were being offered to both employees and managers in most departments.

- Gaps still existed in assessing, monitoring and evaluating the workplace psychological health and safety in the workplace.

Methodology – The 2019 Checklist

In 2019, the Centre launched the second iteration of the Checklist that, in concert with data from the Public Service Employee Survey and the Management Accountability Framework, provides a more complete picture of the Government’s progress toward establishing and maintaining a psychologically healthy and safe workplace.

The collection period for the 2019 Checklist was July 29 to September 13, 2019, and included 17 questions under the same four areas that were a focus in 2017. Many of the questions in 2019 take into account progress made by organizations since the release of the 2017 Checklist results.

The Checklist assesses implementation of the Strategy, and is focused on organizations in the Federal Public Service, defined under the Financial Administration Act as the Core Public Administration and Separate AgenciesFootnote 10. Of the 87 organizationsFootnote 11 invited to participate in the 2019 Checklist, 67 organizations (31 small organizations and 36 large organizations) completed the Checklist, for a total response rate of 77%. Fifty-one organizations completed both the 2017 and 2019 iterations. More information on participating organizations can be found in Annex 2.

Figure 3 - Text version

- 67 organizations completed the Checklist in 2017

- 67 organizations completed the Checklist in 2019

- 51 organizations completed both the 2017 and 2019 Checklists

Throughout the report, we will refer to small and large organizations. Small organizations are considered any organization with fewer than 1,000 employees, while large organizations are considered those with 1,000 employees or more.Footnote 12 These definitions align with the organization sizes used for the Public Service Employee Survey (PSES).

| Organization size under the 2019 Checklist | Organization size under PSES |

|---|---|

| Large (1,000 employees or more) | Very large (10,000 employees or more) |

| Large (5,000 to 9,999 employees) | |

| Medium (1,000 to 4,999 employees) | |

| Small (fewer than 1,000 employees) | Small (500 to 999 employees) |

| Very small (150 to 499 employees) | |

| Micro (fewer than 150 employees) |

Focus Area 1 – Leadership and Governance

-

In this section

Why It Matters

Clear Leadership and Expectations is one of the 13 psychosocial factors that impact employees’ psychological health and safety. Leaders at all levels play a critical role in setting the tone in raising awareness of psychological health and safety and in advocating for workforce well-being.Footnote 13 “Effective leadership increases employee morale, resiliency and trust, and decreases employee frustration and conflict. Good leadership is linked to higher employee well-being scores, a reduction in sick leave usage, and a reduction in early retirements with disability pensions. A leader who demonstrates a commitment to maintaining his or her own physical and psychological health can influence the health of employees, as well as organizational health as a whole.”Footnote 14

What We Found

Organizational Structure

The decision as to where a wellness unit is best placed in an organization is a complex one. Although the case can be made to centralize Human Resources (HR) and Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) functions, factors that should be considered will vary from one organization to the next. Both groups play a critical role in addressing mental health, bringing different perspectives and value to the table. The 2019 Checklist results revealed that 69% of organizations currently house their wellness units and OHS units under the same branch.

Figure 4

69%

of organizations currently house their wellness units and Occupational Health and Safety units under the same branch.

Champions and Sponsors

Mental Health Champions act as the face of the vision, engage unions and employees at all levels, and raise awareness about the importance of psychological health and safety.Footnote 15 By 2017, 93% of organizations had appointed a Mental Health Champion, which is an organization-specific objective under the Strategy.Footnote 16

Supporting the champion are sponsors and senior leaders, who advocate for the allocation of resources to support the PHSMS, and have the authority to make decisions at the highest levels.Footnote 17 The 2019 Checklist results show that 81% of organizations have appointed a project sponsor, which is a key step to establishing the foundation for a PHSMS, as laid out in the third Technical Committee Report “Building Success: A Guide to Establishing and Maintaining a Psychological Health and Safety Management System in the Federal Public Service” (the Third Report).

Figure 5

81%

of organizations have appointed a project sponsor.

Resourcing

According to the second Technical Committee Report (the Second Report), federal organizations are responsible for demonstrating senior leadership support for mental health/a psychologically healthy workplaces by ensuring that resources and infrastructure are adequate to support the PHSMS within the organization.Footnote 18 The 2019 Checklist results indicate that 68% of small organizations and 89% of large organizations have dedicated time and resources to achieve alignment with the Standard. The average number of Full-Time Equivalents (FTEs) dedicated to aligning with the Standard was 0.6 FTEs for small organizations and 1.9 FTEs for large organizations. Based on clarification received from several organizations, in certain cases the number reported represents the resources dedicated solely to mental health while, in other cases, the number reported represents the number resources dedicated to a larger portfolio, including mental health, diversity, inclusion, harassment prevention, values and ethics. In addition, some employees may be working on the mental health file but may not be considered a dedicated resource, which would lead to an underestimation of resources. In the end, 24% of organizations identified finances and/or a lack of resources as a barrier to successfully addressing mental health in the workplace.

Union Representation

As outlined in the Second Report, traditional forms of champion appointment have generally been unilateral on the part of the employer.Footnote 19 To this end, the Second Report provides guidance regarding the champion selection process, recommending that unions be included in decision-making and considered for representation. The 2019 Checklist found that this practice is not yet widespread, with 43% of organizations having considered union representatives in their process to appoint a champion.

Figure 6

43%

of organizations have considered union representation in appointing a champion.

Promising Practices

The 2019 Checklist asked organizations to identify up to three promising practices they have implemented for mental health in the workplace that have shown results. The three most commonly cited promising practices were: promoting mental health activities and services (78%), raising awareness and reducing stigma (75%) and improving mental health literacy (40%).

Figure 7: The three most commonly cited promising practices for addressing mental health in the workplace

78%

of organizations cited promoting mental health activities

75%

of organizations cited raising awareness and reducing stigma

40%

of organizations cited improving mental health literacy

The biggest gap between small and large organizations was in encouraging better disability management (13% of small organizations, compared to 33% of large organizations). Smaller organizations, conversely, were more focused on increasing engagement (29% of small organizations, compared to 25% for large organizations), and improving mental health literacy (48% of small organizations, compared to 33% for large organizations).

The Centre is currently developing a repository that will provide tools, resources and information to support organizations in creating a psychologically healthy and safe workplace, and to support alignment with the Standard. 39% of small organizations and 69% of large organizations said they would be interested in having the Centre assess whether their best practices would be a good fit for the repository.

Focus Area 2 – Awareness and Training

-

In this section

Why It Matters

More than 6.7 million people in Canada are living with a mental health problem or illness today.Footnote 20 But despite how common it is, mental illness continues to be met with widespread stigma. According to the MHCC, “the Carter Center Mental Health Program identified reducing stigma and discrimination as key to improving not only individual quality of life, but mental health systems. This happens by understanding that mental illness is not anyone’s choice and recovery is possible with appropriate treatment and supports.”Footnote 21

On Stigma

“I think it’s just opening up the dialogue…I think that’s going to change many people’s lives in terms of getting the help they need. And secondly, it’s not just about breaking down stigma—breaking down those barriers—it’s about creating resources that are readily available for every single Canadian.”

In order to understand the progress organizations are making in terms of raising awareness, it’s important to look at the results of PSES. Specifically, PSES 2019 found that 73% of employees felt that their department or agency did a good job of raising awareness of mental health in the workplace. This is an improvement from 67% in 2017.Footnote 22 This may be due to the fact that 84% of organizations had included awareness about mental health into their strategic communications plan by 2017.Footnote 23 It suggests that organizations are making improvements, but that there is still an opportunity for growth in this area.

Training is also critical, as it can equip individuals with the ability to prevent psychological harm to themselves and others, as well as provide knowledge of processes, tools and resources for seeking help and supporting employees to help deal with stressors.Footnote 24 The Working Mind, for example, is an education-based program designed to address and promote mental health and reduce the stigma of mental illness in a workplace setting. The training aims to:

- improve short-term performance and long-term mental health outcomes

- reduce barriers to care and encourage early access to care

- provide the tools and resources required to manage and support employees who may be experiencing a mental illness

- assist supervisors in maintaining their own mental health as well as promoting positive mental health in their employeesFootnote 25

Training managers is important, as PSES 2019 found that only 68% of supervisors felt equipped to support employees who are experiencing mental health problems.Footnote 26

The Third Report also notes that federal organizations have an obligation to train all persons involved in the assessment of psychological hazards. At a minimum, this training must include task-related hazard analysis, environmental hazard analysis and workplace inspections. The goal of the training is to equip individuals with the knowledge, skill set and tools to conduct an initial evaluation and to plan for the ongoing measurement and evaluation of any new or existing programs.Footnote 27

The training strategy of each organization will be different, depending on results of the organization’s hazard identification process; however, all federal organizations should develop an evaluation plan to determine the impact training is having on their workforce (e.g. increase in knowledge, behavioural changes, etc.). In this way, organizations can understand what is and is not working, and make adjustments accordingly.

What We Found

In-Class Training

A recent study in the Lancet, found that a four-hour in-class training session for managers lead to a significant reduction in workplace absences. In addition, they found that the return on investment could be tenfold (i.e. a ten dollar savings for every dollar spent).Footnote 28 At the time of the 2017 Checklist, 81% of organizations had delivered mental health training sessions for employees in the past. When organizations were asked more specifically about in-class mental health training in 2019, 66% of organizations reported they have offered in-class mental health training to employees, such as Mental Health First Aid or The Working Mind.

Figure 8

66%

of organizations have offered in-class mental health training such as Mental Health First Aid or The Working Mind.

Further information is needed to understand which training programs are proving to be most effective.

Mandatory Training

Whether mental health training should be part of an organization’s mandatory training curriculum is under the authority of Deputy Heads. The research findings in this area are mixed, with some studies finding that motivation and learning increases when training is mandatory, and others finding the reverse.Footnote 29 Footnote 30 The results of the 2019 Checklist were equally split, with about half of the organizations poled (49%) saying they had made mental health training part of their mandatory training curriculum. Evidence was not gathered on the impact and effectiveness of organizations offering mandatory vs. non-mandatory training.

Figure 9

49%

of organizations have made mental health training part of their mandatory training curriculum.

In the end, the solution may be some combination of mandatory and/or voluntary training, depending on the needs of each organization. Whether training is mandatory or not, some training content may be triggering for individuals managing mental health problems or illnesses. Therefore, organizations should take this into consideration and may consider granting temporary or permanent exemptions to these employees.

Focus Area 3 – Mental Health Support Services

-

In this section

Why It Matters

Psychological Support is another psychosocial factor that impacts employees’ psychological health and safety. According to Guarding Minds at Work, a workplace guide to psychological health and safety, “When employees perceive organizational support, it means they believe their organization values their contributions, is committed to ensuring their psychological well-being, and provides meaningful supports if this well-being is compromised. The more employees feel they have psychological support, the greater their job attachment, job commitment, job satisfaction, job involvement, work/mood positivity, desire to remain with the organization, and job performance.”Footnote 31

The 2017 Checklist found that all organizations had some form of mental health support services available to employees, although the level of support varied widely across organizations. While federal organizations are required to offer services such as an Employee Assistance Programs (EAP) and Informal Conflict Management Services (ICMS), these programs can be operationalized differently by each organization. Furthermore, the need for services such as Return-to-Work Programs, Peer Support Initiatives and Ombuds-type services depends on various factors, including organization size and operational requirements.

What We Found

Return to Work Programs

Under the Strategy, it is an organization-specific objective to “Ensure early intervention and active case management [sometimes referred to as disability management or a disability and case management system], including stay-at-work and return-to-work practices.”Footnote 32 Disability management focuses on absences from work as a result of illness, injury or disability, and on preventing the risks that cause these absences. It is a deliberate and coordinated effort by employers to reduce the occurrence and effect of illness and injury on workforce productivity, and to promote employee attachment.Footnote 33 A return-to-work (RTW) plan/program is a tool for managers to proactively help ill or injured employees return to productive employment in a timely and safe manner.Footnote 34 As per the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety, “the guiding principles are very similar when planning for a return to work due to mental illness as it would be for a physical injury. The focus of the plan should be on the functional abilities of the worker, not the symptoms of the injury or illness, or the causes. You do not need to create a separate RTW program, but be sure your existing program will accommodate workers returning from mental illness-related absences.”Footnote 35

The 2019 Checklist results revealed that 55% of small organizations and 86% of large organizations have a RTW program (disability case management) focused on early intervention for both personal and occupational injuries and/or illnesses of employees. This suggests that additional capacity is necessary for small organizations to strengthen their existing RTW programs and to allow them to offer comprehensive case management services. More information is necessary to determine whether organizations have designed their RTW programs so that they specifically accommodate workers returning from mental illness-related absences.

Figure 10: How many organizations reported having a return to work program?

55%

of small organizations reported having a return-to-work program.

versus

86%

of large organizations reported having a return-to-work program.

Peer Support Initiatives

Peer support initiatives are becoming more common as part of an overall approach to creating psychologically healthy and safe workplaces in Canada.Footnote 36 They are often structured programs where trained employees assist other employees who are struggling with a mental health problem or illness.Footnote 37 Research has linked peer support to reductions in hospitalization for mental health problems, reductions in symptoms of distress, improved social support, and improved quality of life.Footnote 38 The 2019 Checklist results showed that 23% of small organizations and 33% of large organizations have a peer support initiative in place, indicating there are opportunities for growth in this area.

Figure 11 - Text version

33% of large organizations and 23% of small organizations reported having a Peer Support Initiative.

Ombuds-type Resources

In 2018, the Clerk of the Privy Council released a report on the issue of harassment, civility and respect in the workplace. The report recommended that, by March 2019, federal organizations put in place an Ombuds-type function to provide all employees with a trusted, safe space to discuss harassment without fear of reprisal and to help navigate existing systems.Footnote 39 According to the Interdepartmental Committee of Organizational Ombudsmen, there were 20 ombudspersons in place in the Federal Public Service as of November 2019. The 2019 Checklist results revealed that 48% of organizations are served by an ombudsman or an ombuds-type resource, suggesting that a number of organizations are sharing an ombudsman, in order to efficiently leverage resources. This has been confirmed by a number of smaller organizations, many of which share a single ombudsman.

Figure 12

48%

of organizations are served by an ombudsman or an ombuds-type resource.

Organizations are also required to have an ICMS under the Federal Public Sector Labour Relations Act, defined as a systematic approach to managing and resolving conflicts in the workplace quickly and constructively. The 2019 Checklist results showed that, for those organizations served by an ombudsman or an ombuds-type resource, 63% had their Ombudsman office as part of the organization’s ICMS.

In terms of the scope of their role, an ombudsman generally has a broad mandate of investigating complaints against an organization.Footnote 40 This appears to be the case in the Federal Public service as well, with only 6% of those served by an ombudsman or an ombuds-type resource focusing solely on mental health.

Focus Area 4 – Data, Reporting and Continuous Improvement

-

In this section

Why It Matters

The MHCC and its stakeholders consider information to be foundational to achieving its vision of a transformed mental health system in which “All people in Canada have the opportunity to achieve the best possible mental health and well-being.”Footnote 41 As per the Standard, data and information are essential to planning, implementing and maintaining a successful PHSMS.Footnote 42

“The goal is to turn data into information, and information into insight.”

What We Found

Access to Data

While 79% of organizations said they had data and information to monitor and assess organizational needs as identified in the Strategy, 87% of organizations expressed a need for better data or better access to data in this area. Despite this finding, no small organizations and 17% of large organizations named “data, information and/or business intelligence” as one the top three promising practices they had implemented. This indicates there is a gap between the needs of organizations, and actions being taken.

Figure 13: Small and large organizations with the data to assess organizational needs

Small organizations

In 2019, 68% of small organizations reported that they have the data to assess organizational needs, down from 72% in 2017.

Large organizations

In 2019, 89% of large organizations reported that they have the data to assess organizational needs, up from 79% in 2017.

Types of Administrative Data Analyzed

The Standard recommends that organizations review data regarding rates of absenteeism, rates of turnover, return to work and accommodation data, short-term disability and long-term disability costs, EAP data and claims such as benefit utilization rates, disability relapse rates, and workers compensation data. By analyzing this data, organizations can identify the needs, gaps and/or barriers for managing mental health problems in the workplace.Footnote 43

The 2019 Checklist results demonstrate that there is a large variation in the data organizations are assessing:

| Service or benefit | Description | 2019 Checklist findings |

|---|---|---|

| ICMS | ICMS focuses on addressing systemic causes of conflict as well as individual instances of workplace conflict, and offers various services to help both managers and employees.Footnote 44 | 48% of small organizations and 83% of large organizations have analyzed this data. |

| EAP | EAP is a voluntary and confidential service to help employees at all levels, as well as their immediate family members, who have concerns that affect their personal well-being or work performance. EAP also offers specialized services to managers and supervisors.Footnote 45 | 81% of small organizations and 92% of large organizations have analyzed this data. |

| Public Service Health Care Plan (PSHCP) | The PSHCP is one of the largest private health care plans in Canada, providing benefits to over 600,000 plan members and their dependants.Footnote 46 The plan provides coverage for services such as psychologists,Footnote 47 as well as long term disability insurance for those suffering from mental health problems and illnesses.Footnote 48 According to the MHCC, about 70% of disability cost for Canadians are mental health-related,Footnote 49 which means that addressing mental health in the workplace could not only benefit employees, but lead to considerable cost savings on the part of the employer. | 19% of small organizations and 47% of large organizations have analyzed this data. |

This suggests that organizations could benefit from support and tools in implementing a more consistent, enterprise-wide approach to data and business intelligence.

Employee Surveys

Employee sentiment is an important piece to consider when developing a PHSMS.Footnote 50 In 2017, new stress and well-being questions were introduced to the Public Service Employee Survey (PSES), to:

- assess employee stress levels

- determine if employees felt emotionally drained

- identify stress factors

- measure their overall sense of workplace psychological healthFootnote 51

PSES is now conducted annually, providing a more regular gauge of the mental health of employees and workplaces.

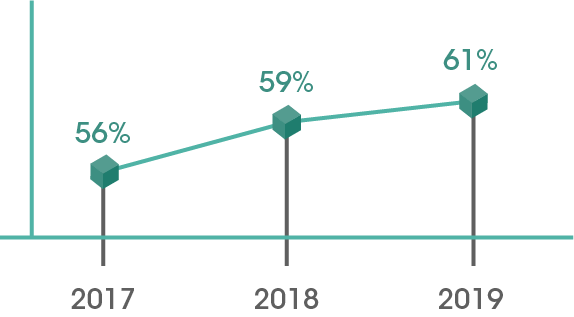

Figure 14 - Text version

In 2017, 56% of employees described their workplace as being psychologically healthy in PSES, compared to 59% in 2018 and 61% in 2019.

The 2019 Checklist poled organizations as to whether they were using additional tools to measure employee opinions on psychological health and safety. 32% of small organizations and 56% of large organizations indicated they have used additional tools, with 33% of organizations having used the Guarding Minds at Work as the basis for their content. While Guarding Minds at Work has the advantage of being a scientifically valid survey tool with a link to the 13 psychosocial factors, other organizations felt that it was important to develop their own content (37%) or use other sources as the foundation of their surveys (30%). Although a consistent government-wide approach is important when addressing mental health, it is also important that departments are able to use measurement tools that meet the specific needs of their organizations.

Psychological Hazards Identification

The Standard provides a framework for identifying and eliminating hazards that pose a risk of psychological harm to workers.Footnote 52 To support federal organizations in aligning with the Standard, the JTF on Mental Health prepared the Third Report to guide organizations in developing and implementing a PHSMS in the context of the Federal Public Service.Footnote 53 According to the MAF 2017–2018, 35% of small organizations and 48% of large organizations have performed a psychological hazard analysis informed by survey results, and 70% of small organizations and 84% of large organizations have reviewed workplace programs and policies through a mental health lens.Footnote 54 The 2019 Checklist results found that 26% of small organizations and 39% of large organizations have used Guarding Minds at Work to support their hazard identification process.

Figure 15: Percentage of organizations that have used Guarding Minds at Work to identify and assess possible psychological hazards in the workplace

26%

of small organizations have used Guarding Minds at Work to identify and assess possible psychological hazards in the workplace.

versus

39%

of large organizations have used Guarding Minds at Work to identify and assess possible psychological hazards in the workplace.

Areas Requiring Support

The 2019 Checklist asked organizations to identify areas they felt required further support. The results were as follows (from most cited to least cited area requiring support):

| Area requiring further support | # of organization that identified area requiring support |

|---|---|

| Conducting a psychological hazard analysis and aligning with the Standard | 17 |

| Resourcing to implement the Strategy and align to the Standard | 16 |

| Building capacity for enhanced data and business intelligence | 15 |

| Implementing a public service standard or approach | 9 |

| Increasing MH training/awareness | 8 |

| Implementing organization-specific initiatives | 7 |

| Enhancing knowledge sharing and collaboration | 6 |

| Selecting evidence-based solutions (based on the results of a risk assessment) | 5 |

| Providing training to managers | 3 |

| Increasing regional inclusion | 3 |

| Developing peer support networks | 3 |

| Promoting and increasing the utilization of the Employee Assistance Program | 2 |

| Enhancing support from the Centre | 2 |

| Building a disability management system | 2 |

| Increasing employees participation rates at mental health/wellness events | 1 |

| Securing and supporting Mental Health Champions | 1 |

| Implementing Bill C65 | 1 |

In some cases, addressing these barriers will be the responsibility of individual organizations, while in other cases, enterprise-wide efforts will be required.

The Centre of Expertise for Mental Health in the Workplace

Support for Conducting a Psychological Hazard Analysis and Aligning with the Standard

To support organizations in conducting a psychological hazard analysis and aligning with the Standard, the Centre held a two-day learning event for members of the OPI on Mental Health in November 2019. The training from Workplace Safety and Prevention Services (WSPS) and the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety (CCOHS) was well received, and representatives from across the government were in attendance.

In addition, the Federal Workplace Well-Being Network (FWWN), in collaboration with the Centre, created a series of “Power Chats”, designed as interactive learning events to support the implementation of the Strategy. The events are open to all public servants across the Federal Public Service, and include talks on topics such as “Implementing a Psychological Health and Safety Management System.”

As discussed earlier in this report, the JTF on Mental Health Technical Committee also published the Third Report in January 2018—a guide on developing and implementing a PHSMS in the Federal Public Service.Footnote 55 As organizations are still reporting confusion on this topic despite the guide, further consultation is required to determine whether awareness of the guide itself is insufficient, or whether organizations are still not clear on how to operationalize the process.

Support for Resourcing

In May 2019, the Centre established the Office of Primary Interest (OPI) on Mental Health to support federal organizations’ efforts to move the Strategy forward and to align with the Standard. By engaging this community of practice, the Centre provides expertise and guidance, shares enterprise-wide updates, builds capacity through training, and supports collaboration across the Federal Public Service. By sharing documentation, lessons learned, best practices, etc., efficiencies will be realized, and will address some of the concerns for additional resources. As of November 2019, the OPI Network consisted of 120 members representing 68 federal organizations. The OPI Network meets virtually on a monthly basis, with semi-annual in-person learning events.

The Centre is also developing a repository that will provide tools, resources and information to support organizations in creating a psychologically healthy and safe workplace, and to support alignment to the Standard. The key objectives of the repository include:

- providing a central repository with easy access to useful resources, research and tools pertaining to mental health and wellness

- reducing time for organizations in researching and implementing tools, research and training

- providing a platform for organizations to showcase leading best practices

Thirty-nine percent of small organizations and 69% of large organizations said they would be interested in having the Centre assess whether their best practices would be a good fit for the repository.

Support for Data and Business Intelligence

In 2017, the Workplace Mental Health Performance Measurement Steering Committee (previously the Workplace Mental Health Performance Measurement Inter-Departmental Committee) was established to support goal three of the Strategy (focused on measurement and reporting).Footnote 56 The group is currently developing a measurement strategy for the Federal Public Service to assess organizational performance against the 13 psychosocial risk factors from the Standard. Providing organizations with an enterprise-wide approach should reduce some of the burden on individual organizations to gather and compile the information themselves.

Conclusion

By looking at data from various sources, a picture has started to emerge of organizations’ progress to align with the Standard, as laid out in the Third Report:

- 100% of small organizations and 94% of large organizations have appointed a Mental Health Champion (the 2017 Checklist)

- 81% of small organizations and 81% of large organizations have appointed a project sponsor (the 2019 Checklist)

- 84% of small organizations and 88% of large organizations have included awareness about mental health in their strategic communications plan (the 2017 Checklist)

- 35% of small organizations and 48% of large organizations have performed a psychological hazard analysis informed by MAF results (MAF 2017–2018)

- 70% percent of small organizations and 84% of large organizations have reviewed workplace programs and policies from a mental health lens (MAF 2017–2018)

While progress is being made, the results of 2019 Checklist also identified opportunities for growth. Based on these results, organizations should consider focusing on:

- ensuring adequate resources are available to support their Mental Health Action Plans, as required by the Strategy

- enhancing support services such as disability case management systems, ombuds-type resources and peer support initiatives

- ensuring those leading mental health efforts have adequate training, specifically in hazard identification and in establishing a Psychological Health and Safety Management System

- identifying and securing sources of data that will enhance the understanding of the psychological health of their organization

Workplace mental health is a priority for the Federal Public Service. A psychologically healthy and safe workplace is the foundation of an effective, productive and engaged workforce. While organizations are making progress on implementing the Strategy and aligning to the Standard, there is still work left to do. The Centre of Expertise on Mental Health in the Workplace will continue to support organizations in making advancements in addressing mental health in the workplace by:

- providing direct support and guidance to organizations implementing action plans to address mental health and/or align with the Standard

- building capacity and connection through networks and communities of practice

- strengthening data and business intelligence

- providing access to credible leading practices, resources and tools

- raising awareness of mental health problems and illnesses

As diversity, harassment, violence and inclusion intersect with mental health and play an important part in aligning with the Standard,Footnote 57 the Centre will consider the intersections of these factors as it works toward an integrated agenda to achieve workplace wellness.

As stated in the Strategy, “the health and wellness of the Federal Public Service and its employees are vital to each organization’s success. We are at our best when our bodies, minds and workplaces are healthy, respectful and supportive, enabling us to work, build and innovate.”Footnote 58 We have established our Vision, developed a Strategy, and have the tools in place to achieve success. We must now work together to create a culture that enshrines psychological health, safety and well-being in all aspects of the workplace through collaboration, inclusivity and respect.Footnote 59

Annex 1 – Results Tables

| Small | Large | All | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % of organizations with an Occupational Health and Safety unit under the same branch as their wellness unit | 61% | 75% | 69% |

| % of organizations that have a project sponsor | 81% | 81% | 81% |

| % of organizations that have dedicated time and resources for achieving alignment to the National Standard of Canada for Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace | 68% | 89% | 79% |

| % of organizations that have considered union representatives in their process to appoint a champion(s) for mental health | 45% | 42% | 43% |

| % of organizations that would like to test the broader application of the promising practices they have implemented through the Centre’s evaluation process | 39% | 69% | 55% |

| Small | Large | All | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % of organizations that have offered in-class mental health training sessions to employees, such as Mental Health First Aid or The Working Mind | 68% | 64% | 66% |

| % of organizations that have included mental health in the workplace training as part of their mandatory training curriculum | 45% | 53% | 49% |

| Small | Large | All | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % of organizations that have a return-to-work program (disability case management) focused on early intervention for both personal and occupational injuries and/or illnesses of employees | 55% | 86% | 72% |

| % of organizations that have a peer support initiative | 23% | 33% | 28% |

| % of organizations that have an ombudsperson | 45% | 50% | 48% |

| For those organizations with an ombudsperson, % where the ombudsperson is part of Informal Conflict Management | 57% | 67% | 63% |

| For those organizations with an ombudsperson, % where ombudsperson is focused solely on mental health | 7% | 6% | 6% |

| Small | Large | All | |

|---|---|---|---|

| % of organizations that have data and information to monitor and assess organizational needs as identified in the Federal Public Service Workplace Mental Health Strategy (MHS) | 68% | 89% | 79% |

| % of organizations that have a need for better data or better access to data in these areas | 81% | 92% | 87% |

| % of organizations that have analyzed Informal Conflict Management Services data | 48% | 83% | 67% |

| % of organizations that have analyzed Employee Assistance Program data | 81% | 92% | 87% |

| % of organizations that have analyzed Public Service Health Care Plan data | 19% | 47% | 34% |

| % of organizations that have fielded an organization-specific survey of their employees on psychological health and safety in the workplace (excluding the Public Service Employee Survey) | 32% | 56% | 45% |

| Of those organizations that fielded a org-specific survey, % that used Guarding Minds at Work as the basis for their content | 60% | 20% | 33% |

| Of those organizations that fielded a org-specific survey, % that developed their own content | 10% | 50% | 16% |

| Of those organizations that fielded a org-specific survey, % that used another source as the basis for their content | 30% | 30% | 13% |

| % of organizations that used the worksheets provided by Guarding Minds at Work to help identify and assess possible psychological hazards in our workplace | 26% | 39% | 33% |

Annex 2 – List of Participating Organizations

- Administrative Tribunals Support Service of Canada

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

- Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency

- Canada Border Services Agency

- Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions

- Canada Revenue Agency

- Canada School of Public Service

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency

- Canadian Grain Commission

- Canadian Heritage

- Canadian Human Rights Commission

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat

- Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency

- Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission

- Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission

- Canadian Security Intelligence Service

- Canadian Space Agency

- Canadian Transportation Agency

- Communications Security Establishment

- Correctional Service Canada

- Courts Administration Service

- Department of Finance Canada

- Department of Justice Canada

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- Environment and Climate Change Canada

- Farm Products Council of Canada

- Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario

- Financial Consumer Agency of Canada

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- Global Affairs Canada

- Health Canada

- Immigration and Refugees Board of Canada

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- Indigenous Services Canada & Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

- Infrastructure Canada

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

- Library and Archives Canada

- Military Grievances External Review Committee

- Military Police Complaints Commission of Canada

- National Defence

- National Film Board of Canada

- National Research Council Canada

- Natural Resources Canada

- Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada

- Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada

- Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

- Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada

- Office of the Registrar of the Supreme Court of Canada

- Parks Canada

- Parole Board of Canada

- Patented Medicine Prices Review Board

- Privy Council Office

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- Public Prosecution Service of Canada

- Public Safety Canada

- Public Service Commission

- Public Services and Procurement Canada

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- Shared Services Canada

- Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council

- Statistics Canada

- Transport Canada

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

- Veterans Affairs Canada

- Veterans Review and Appeal Board