ARCHIVED – 2021 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration

For the period ending

December 31, 2020

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

ISSN 1706-3329

Table of Contents

- Message from the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship

- Key highlights for immigration to Canada 2020

- Introduction

- Immigration and the COVID‑19 pandemic: challenges, opportunities and a driver for Canada’s recovery

- Temporary resident programs and volumes

- Permanent immigration to Canada

- Francophone immigration outside of Quebec

- International engagement

- Canada’s next permanent resident Immigration Levels Plan

- Gender-Based Analysis Plus

- Annex 1: Section 94 and Section 22.1 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

- Annex 2: Tables

- Annex 3: Temporary migration reporting

- Annex 4: Ministerial Instructions

Message from the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship

As Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship, I am pleased to present the 2021 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration.

Year after year, Canada has maintained its enduring tradition of welcoming newcomers from every corner of the globe and offering protection to some of the world’s most vulnerable. We have long recognized that immigration provides essential contributions to Canada’s culture, economy, and population growth. Our cultural diversity and economic prosperity could not exist without newcomers. Their contributions enrich Canadian communities and the lives of everyone who lives here.

In 2020, our ability to meet the number of newcomers we had expected to welcome was interrupted by the COVID‑19 pandemic. We have continued to recognize the importance of immigration, and in particular its important contribution to the post-pandemic economic recovery.

The pandemic had deep and sudden impacts on the Department’s overall operations, much of which were paper-based. Due to a number of factors, including the significant challenges posed by border closures and the closing of offices in Canada and around the world, we experienced processing backlogs and a severely reduced ability to process permanent resident applications. Almost all Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada staff began working from home, juggling family and professional priorities in ways they never imagined, and quickly implementing and adapting to new digital processes.

Furthermore, statistics demonstrate that immigrants themselves were particularly hard-hit by the COVID‑19 pandemic, including those working to keep Canadians healthy and those who kept food on our tables often in challenging circumstances. They also experienced higher unemployment as they worked in the vulnerable hospitality and service sectors.

Fortunately, the Department was able to adapt to the immense pressures posed by the pandemic. Our pivot to virtual processes and services took an incredible effort, representing the fruit of the expertise and work of people throughout the Department. Moving forward, this work to make our immigration system more resilient and efficient will continue through a digital modernization plan. Similarly, we remained flexible by adjusting our programs and policies to address challenges stemming from the COVID‑19 pandemic.

In spite of the unprecedented challenges, the Department can take pride in a number of achievements. Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada facilitated the entry of thousands of essential agricultural and health care workers, working in close partnership with other government departments and provinces/territories. In 2020, the temporary public policy to facilitate the granting of permanent residence for certain refugee claimants working in the health care sector during the COVID‑19 pandemic was introduced, and we continued to resettle urgent protection cases. We also created special public policies to assist international students in Canada and abroad.

Nearly 185,000 permanent residents were welcomed in 2020, supported by more than 500 Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada-funded settlement service provider organizations. This was short of the 2020 permanent resident target, but an impressive achievement in view of border closures and restrictions, office closures, and other challenges over the past year.

At the same time, the Department continues to support the Government of Canada’s commitment to support the growth of French-speaking immigrants outside of Quebec, and to enhance the vitality of French linguistic minority communities in Canada. To that end, the Department increased the number of points for French-speaking and bilingual candidates under the Express Entry system and strengthened Francophone settlement services, which provided essential supports to newcomers during the pandemic.

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada remains committed to evidence-based decision-making and applying Gender-Based Analysis Plus to the Department’s work. Throughout the last year, the Department has made some important progress on its Gender-Based Analysis Plus commitments. Moreover, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada established the Anti-Racism Task Force to combat systemic racism and promote greater equity, both within the organization and with respect to the design and implementation of its policies and programs. The Department’s Sex and Gender Identifier Policy was also updated to improve outcomes for LGBTQI populations.

In addition, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada resettled refugee women and children through Canada’s Assistance to Women at Risk Program, and engaged in measures to help newcomers leave situations of family violence, which have only been exacerbated by the pandemic. Moreover, Canada leads by example in our commitment to advocating for gender diversity at the international level. Canada is a Champion country of the Global Compact for Migration, which allows us to share best practices related to gender-responsive migration management.

Going forward, our immigration system will continue to be essential, as Canada works to build a safe and prosperous future. I invite you to learn more about the Department’s accomplishments and priorities in the Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration.

Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship

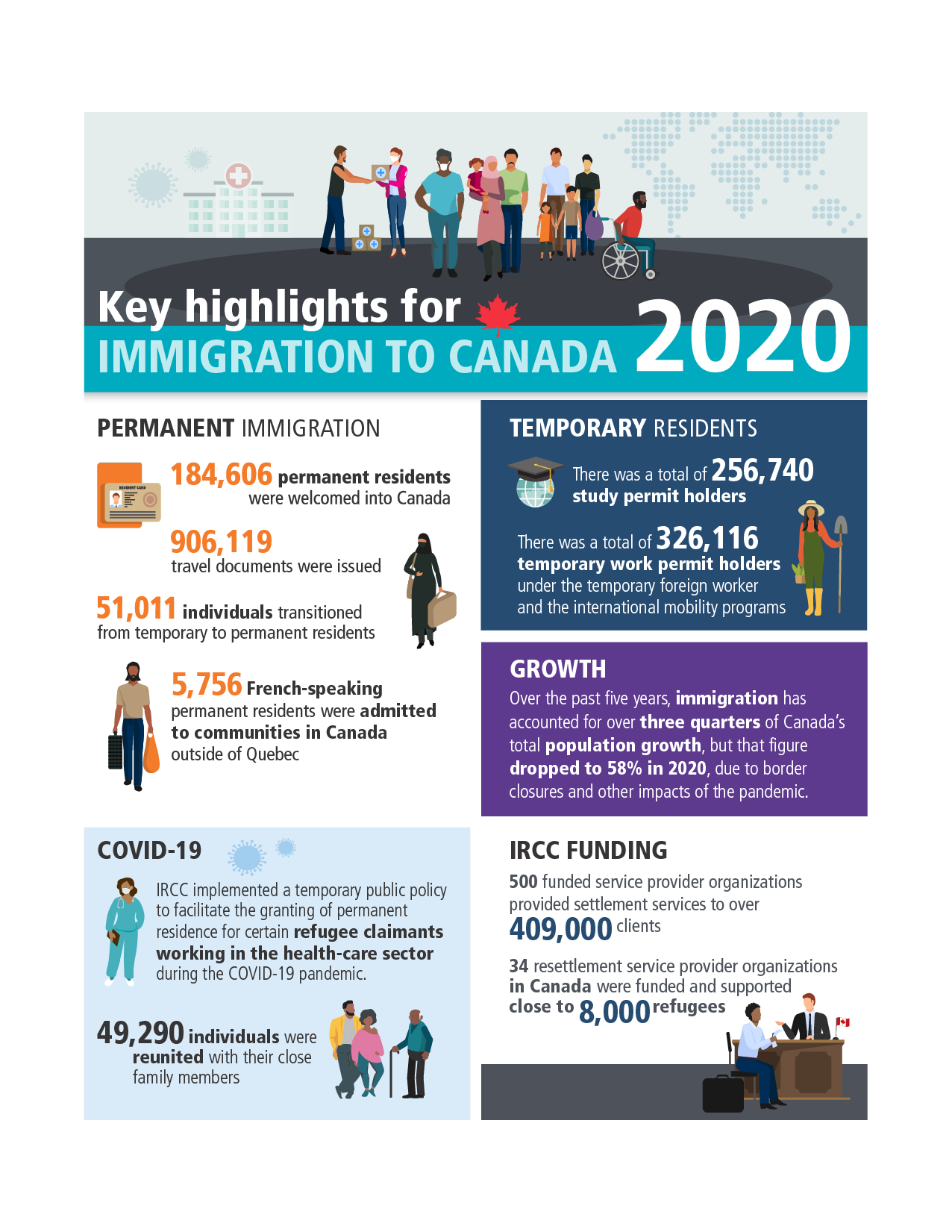

Key highlights for immigration to Canada 2020

Text version: Key Highlights for Immigration to Canada 2020

Permanent Immigration

184,606 permanent residents were welcomed into Canada

906,119 Travel documents were issued

51,011 individuals transitioned from temporary to permanent residents

5,756 French-speaking permanent residents were admitted to communities in Canada outside of Quebec

Covid-19

IRCC implemented a temporary public policy to facilitate the granting of permanent residence for certain refugee claimants working in the health care sector during the COVID‑19 pandemic

49,290 individuals were reunited with their close family members

Temporary Residents

There was a total of 256,740 study permit holders

There was a total of 326,116 temporary work permit holders under the temporary foreign worker and international mobility programs

Growth

Over the past five years, immigration has accounted for over three quarters of Canada’s total population growth, but that figure dropped to 58% in 2020, due to border closures and other impacts of the pandemic.

IRCC Funding

500 funded service provider organizations provided settlement services to over 409,000 clients.

34 resettlement service provider organizations in Canada were funded and supported close to 8,000 refugees

Introduction

The Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration is a requirement of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, and it provides the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship with the opportunity to inform Parliament and Canadians of key highlights and related information on immigration to Canada. It also offers information on successes and challenges in welcoming newcomers to Canada.

This report sets out information and statistical details regarding temporary resident volumes and permanent resident admissions, and provides the planned number of upcoming permanent resident admissions. In addition, it outlines the efforts undertaken with provinces and territories in our shared responsibility of supporting immigration, highlights efforts to support and promote Francophone immigration, and ends with an analysis of gender and diversity considerations in Canada’s approach to immigration.

The 2021 Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration focuses on immigration results that were achieved in 2020, although publication takes place in the following calendar year to allow Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) the opportunity to obtain final information from the preceding calendar year.

About the data in this report

Admissions data can be found in Annexes 2 and 3, as well as on the Government of Canada’s Open data portal and in the facts and figures published by IRCC.

Data in this report that were derived from IRCC sources may differ from those reported in other publications; these differences reflect typical adjustments to IRCC’s administrative data files over time. As the data in this report are taken from a single point in time, it is expected that they will change slightly as additional information becomes available.

Immigration and the COVID‑19 pandemic: challenges, opportunities, and a driver for Canada’s recovery

Throughout history, Canada has experienced the economic, demographic, social, and cultural benefits of immigration. Permanent and temporary residents play an important role in filling gaps in the labour market and bring their talent, ideas and perspectives, as well as their culture and heritage, to enrich Canada’s social fabric. Every year, Canada welcomes thousands of temporary foreign workers (TFWs), students, visitors, and permanent residents. Canada also supports the reunification of families and the protection of refugees and persons at risk.

While immigration remains important for Canada, it was deeply affected by COVID‑19 in 2020. On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared the COVID‑19 outbreak to be a global pandemic. Border restrictions and public health measures, including limiting access to Canada to certain immigrant groups, in addition to quarantine and self-isolation for persons travelling to Canada, were put in place. This context, including the significant impacts of closed borders, created real barriers for individuals seeking permanent or temporary residency, and for asylum seekers and refugees seeking to resettle in Canada. In fact, only 184,606 permanent residents were admitted in 2020, out of the 341,000 target for 2020, from the 2020-2022 Levels Plan.

The pandemic also impacted the operational capacity, including the use of paper-based operations, of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC), as the majority of employees were unable to work on-site/in office for most of 2020, and a number of international and provincial/territorial lockdowns led to the closure of offices and a reduction of in-person services.

To respond to the challenges posed by COVID‑19 – both in terms of the immigration system at large and the organizational capacity of the Department – IRCC took great strides to move away from paper-based processes toward a modern, digital system and implemented a number of facilitative measures. This Annual Report provides information on the extraordinary context of 2020, and the impacts of COVID‑19 on immigration in Canada, as well as the many innovations that were made to our operations and in our programs and policies.

Canada’s Temporary and Permanent Residents and the impacts of COVID‑19

COVID‑19, including border measures, closed offices and the need for social distancing, has impacted permanent and temporary residents throughout the year. Existing health, economic, and social outcome inequities were exacerbated by the pandemic, where some populations, including newcomers, were at greater risk of being exposed to COVID‑19, as well as more serious outcomes. Statistics show that although immigrants made up 20% of the total Canadian population younger than 65, they accounted for 30% of all COVID‑19 deaths among those younger than 65. Statistics Canada suggests this could be related to a range of factors, including that immigrants may have lower incomes, be more likely to live in overcrowded dwellings or multigenerational households, and more likely to be employed in essential work and occupations associated with a greater risk of infection.Footnote 1

Permanent and Temporary Residents felt the weight of the COVID‑19 pandemic

Text version: Permanent and Temporary residents felt the weight of the COVID‑19 pandemic

Due to border closures and lockdowns, many permanent and temporary residents experienced processing and travel delays, and permanent resident applicants were unable to travel to Canada from overseas.

Immigrants were at a greater risk of losing their jobs than Canadian‑born.

Immigrants are at a greater risk of being exposed to COVID‑19 because they are disproportionately employed in front‑line and essential service jobs.

International students were affected by border closures and had to shift to online classes.

What’s more, the pandemic affected the employment status of many of Canada’s temporary and permanent residents.Footnote 2Footnote 3 Statistics show that newcomers to Canada were more likely to lose employment once the pandemic hit, in comparison to the Canadian-born population.Footnote 4 The unemployment rate for recent temporary and permanent residents peaked at 17.3% at the beginning of the pandemic, in comparison to 13.5% for the Canadian-born population and long-term immigrants and refugees.Footnote 5 Additionally, unemployment was much higher among racialized populations.Footnote 6

Spotlight on Discrimination and Inequities related to Immigration

According to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), in its Chief Public Health Officer of Canada's Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2020: From Risk to Resilience: An equity approach to COVID‑19 (October 2020),

“The structural determinants of health — such as social and economic policies, governance structures and societal values and norms — drive health inequities because they shape the ways that power, money, and resources are distributed in society which provide individuals with greater or lesser ability to have control over their health. Stigma and discrimination are embedded in these systems and influence who has power and privilege. For example, people can occupy different positions on the social or economic hierarchy, based on how society treats them according to factors such as their perceived race, sexual orientation, ability, sex, gender, religion or age”.Footnote 7

Low-income workers were found to be at greater risk of exposure to COVID‑19 due to the often precarious nature of their employment, particularly for women, immigrants, and racialized workers.Footnote 8 Specifically, workers in the agricultural and meat processing sectors were at increased risk of contracting the virus, stemming from outbreaks at their workplace and places of residence. In Canada, approximately 41% of meat processing workers are members of racialized groups, compared to 21% of the workforce in general.Footnote 9 TFWs in the agriculture sector also experienced increased exposure to COVID‑19 as a result of poor housing and working conditions.Footnote 10

Lockdowns due to the pandemic affected many families of permanent and temporary residents in various ways, including the requirement for children to stay home during the pandemic. This forced many people, primarily women, to leave employment permanently or temporarily, or to manage having children at home while working from home.Footnote 11

Immigration Success Story for 2020: Teaching children for free during a pandemic

Kavita Dau immigrated to Canada at age 15 and jumped straight into the International Baccalaureate Diploma Program, graduating two years later with results in the top 3% worldwide. Kavita, who is now in her early twenties, founded Dau Academy as a way to improve students’ exam results and build their confidence in school. During the pandemic, Kavita decided to keep teaching for free, via Zoom, to mitigate some of the effects of the pandemic on student learning. Kavita’s contributions to children’s learning over the course of the pandemic have been praised by Leah Coss, Founder & CEO, Build a Biz Kids, and Manisha Narula, Director of Community, League of Innovators.

GBA Plus Snapshot: The impacts of COVID‑19 on women

Women who are newcomers to Canada, including permanent or temporary residents, experienced COVID‑19 in different, and often more negative ways, than others in Canada. Women continue to be primarily responsible for non-paid care work.Footnote 12 During the pandemic, many parents, notably women, stayed home with children during lockdowns, and were either unable to go to work, or needed to juggle working at home while taking care of their children.Footnote 13

In addition, women who were still employed during the pandemic faced particular health and socioeconomic threats. From increased exposure to the virus due to their overrepresentation in frontline services, to being economically vulnerable due to short-term and other precarious work, to increased sexual and gender-based violence in the context of lockdowns and social isolation, women have been among the hardest hit by COVID‑19.

Furthermore, the majority of staff employed in nursing facilities, residential care facilities, and home care continue to be women, stemming from long-standing conceptions about the gendered nature of work. Women also tend to occupy more positions than men in nursing and health-care support professions. In 2016, almost 9 in 10 employees in nursing and health care support professions were women.Footnote 14

Women who recently immigrated to Canada also faced an increase in employment loss as a result of the pandemic. Statistics show that recent women immigrants experienced the largest increase in the rate of transition to non-employment at the beginning of the pandemic. Almost 20% of recent women immigrants employed in March 2020 were not employed in April 2020, which is 7% higher than among Canadian-born women.Footnote 15

How permanent and temporary residents contributed to Canada’s resilience throughout the COVID‑19 pandemic

Canada’s permanent and temporary residents supported Canada’s resilience during the pandemic, particularly through their work in long term care, health care, the food sector and other frontline services.

TFWs contributed significantly to Canada’s agriculture and crop production sectors over the course of the pandemic, with some of these services being deemed to be of an essential nature over this period.

Immigration Success Story for 2020: Khabat Alissa (Issa) volunteered his time for making and donating face masks during the pandemic

Tailoring is a passion for Khabat Alissa (Issa), who worked as a tailor in Syria before immigrating with his family to Nova Scotia in 2016. Upon his arrival, Issa began working at his cousin’s tailor shop in Bridgewater and, with the support of his cousins and community, opened his own tailor shop in Enfield just three years later.

When the COVID‑19 pandemic hit Canada, interrupting his regular tailoring business, Issa volunteered his time and talents to help the best way he knew how—by sewing.

“Issa donated face masks to all the local essential workers and anyone else in the community who was in need of one,” says Trish Pittman, local volunteer first responder and pharmacy technician.

Soon, requests poured in from around the province. At the height of the pandemic, Issa was sewing upwards of 100 masks per day. He estimates that he has donated over 3,000 masks, though for Issa the focus was on helping his community during a time of need.

Beyond stitching the masks, Issa personally delivered them to fire fighters, paramedics and first responders. He also made deliveries to seniors’ homes so the community’s most vulnerable populations could stay safe.

“He took care of all the first responders in the area first and then posted on social media that others in the community could come to the shop and pick up a free face mask,” says Todd Pepperdine, the Fire Chief at the Enfield Fire Department. “It’s amazing to think of what he’s contributed by reaching into his own pockets.”

As a recent immigrant and new business owner, Issa is working past language barriers to be of help to those in need and to put his community first. He is dreaming of opening another tailor shop in Halifax one day.

How IRCC responded to the COVID‑19 pandemic

IRCC made internal adjustments to respond and better adapt its services in the context of COVID‑19

From border closures/restrictions and growing processing backlogs, to reduced capacity at domestic and international offices and the general shift to remote work, the ongoing pandemic caused significant disruptions to IRCC operations and exacerbated existing challenges. The pandemic also impacted IRCC programs and services throughout 2020, in particular those related to the temporary entry of visitors, international students and temporary workers, asylum claimants, the selection of potential permanent residents for immigration, and the granting of citizenship to eligible permanent residents.

The Department responded by ramping up the transformation and digitization of programs and services, strengthening information technology networks and rolling out equipment to enable employees to work remotely, allowing continued client support with the establishment of a virtual client support centre. The Department also found new ways to engage with domestic and international partners in a global context characterized by rapidly emerging issues, complexity and uncertainty.

IRCC introduced many facilitative measures to mitigate the impacts of the COVID‑19 pandemic

Since the beginning of the pandemic, IRCC has introduced a number of temporary public policies and facilitative measures to mitigate the impacts of COVID‑19 on applicants, and to continue to attract newcomers to fill gaps in Canada’s labour market. This included measures to facilitate the arrival of immediate and extended family members of Canadian citizens, persons registered under the Indian Act, permanent residents, and immediate family members of temporary residents of Canada in order to reunite families who might have otherwise been separated due to the travel restrictions.

Spotlight: Priority Processing for Temporary Residents who are Essential Workers

Public Safety Canada has developed a set of functions deemed essential to help provinces/territories protect their communities while maintaining the reliable operation of critical infrastructure services and functions to ensure the health, safety, and economic well-being of the population. These include, but are not limited to, the functions performed by health care workers, critical infrastructure workers (e.g., hydro and natural gas), and workers who are essential to supply critical goods such as food and medicines. In terms of temporary resident priority processing, the continued focus is on processing applications from essential workers to ensure continuity of these services for Canadians.

Permanent Residents

The pandemic negatively affected IRCC’s ability to review and process permanent resident applications, and most biometrics collection service points were temporary closed. In response, several facilitative measures were introduced, including exempting permanent residence applicants – whether in or outside Canada – from the biometrics collection requirement if they had previously provided their biometrics within the last 10 years. In lieu of new collections, the previously collected biometrics were reused for screening purposes to support application processing and to ensure the safety and security of all Canadians.

For approved applicants outside of Canada, the Department authorized longer validity periods on key travel documents, such as the confirmation of permanent residence and permanent resident visas, until travel restrictions eased. For approved applicants inside Canada, the in-person interview was waived in order to confer status. In 2020, IRCC also implemented the new Permanent Resident Confirmation Portal to permit the online verification of requirements for permanent resident admissions for applicants who are physically in Canada.

International Students

During the pandemic, travel restrictions and border closures prevented some international students from travelling to Canada, even in cases where their study permit application was finalized and approved. Furthermore, some international students in Canada lost income from part-time jobs due to closures of non-essential businesses and they were separated from their family members due to travel restrictions and border closures.Footnote 16 An IRCC survey administered in July 2020 found that 33% of 15,627 international students surveyed in Canada lost a job or a placement as a result of the COVID‑19 pandemic, and 22% saw their hours of work reduced.

In close collaboration with provinces/territories and key stakeholders, IRCC created and implemented a range of policies to respond to the needs of international students in the pandemic context. For example, IRCC introduced two-stage processing for students who were not able to submit a complete application. This included a first-stage eligibility assessment and a final decision based on admissibility requirements in the second stage. In addition, IRCC made changes to the Post-Graduation Work Permit Program to allow students to continue their academic programs online from abroad while travel restrictions were in effect. IRCC also lifted restrictions to allow international students in Canada to work over 20 hours per week in off-campus jobs during an academic term, which allowed them to maintain a connection to the labour force and to help provide essential services to Canadians in some cases. As a temporary facilitative measure, some foreign nationals in Canada, including in the case of study permit and study permit renewals, were exempted from the biometrics collection requirements of their application.

Supporting international students remained a priority throughout the pandemic. Although the Canadian border remained closed to non-essential travel, new measures came into effect on October 20, 2020 allowing international students that were study permit holders or that have been approved for a study permit to be exempt from COVID‑19 travel restrictions, provided that they met the requirement of attending a designated learning institution that has a provincially or territorially approved COVID‑19 readiness plans.

Temporary Foreign Workers

Canada recognized the exceptional contribution of TFWs who performed or supported essential services during the pandemic. IRCC works closely with Employment and Social Development Canada, provinces/territories and industries to support labour market needs. In 2020, a number of facilitative measures were introduced to ensure TFWs could still travel to Canada during the pandemic, while protecting public health.

There were new regulations for TFWs to follow public health measures including mandatory isolation or quarantine when they first arrived in Canada. The regulations also required employers to pay workers their wages during their quarantine upon entry to Canada and not prevent workers from meeting public health requirements.

IRCC also created special temporary policies to alleviate barriers for TFWs during the pandemic. For example, a temporary public policy was introduced in May 2020 for TFWs to be granted an interim work authorization within a short time frame in new positions while awaiting a decision on their new work permit application. This public policy allowed TFWs to fill urgent labour needs including in the agriculture, agri-food, and health care sectors.

To ensure the ongoing and timely arrival of TFWs to work in key industries, the Department prioritized the processing of work permit applications for foreign nationals seeking to enter to fill positions in critical sectors such as health care, transportation and agriculture. In July 2020, the Department also implemented a temporary public policy that extended the time temporary residents have to restore their status after it expires (beyond the standard 90-day window) and that allows them to work while they wait for their restoration application to be finalized. In August 2020, an additional temporary public policy was introduced allowing visitors to apply for an employer-specific work permit without having to leave the country, providing they had a valid work permit in the past 12 months.

Looking ahead to Canada’s post-COVID‑19 recovery

Immigration in Canada has a significant role in the country’s demographic and labour growth and has many social and cultural benefits. While the role of immigration in Canada’s post-COVID‑19 economic recovery is still taking shape, past experience suggests that immigration will have a positive impact on Canada’s economy.

Immigration plays a key role for Canada’s population growth:

- Immigrants make up a significant and increasing share of the Canadian population. Four in ten people in Canada are either immigrants or children of immigrants.Footnote 17

- Immigration has become the primary source of population growth in Canada in recent decades, driving more than 80% of Canada’s population growth.Footnote 18 Without immigration, the Canadian population is projected to start declining in about 10 years.Footnote 19

Immigration also contributes to Canada’s labour force, which will be particularly important during Canada’s post-pandemic recovery:

- Just over one-fourth of the core-working age population (those aged 25 to 54) in Canada is made up of immigrants.Footnote 20

- Immigration will be essential to the growth of the working age population; without it, Canada’s core-working age population is projected to decrease in the next 20 years.Footnote 21 Immigrants account for one out of every four health-care sector workers.Footnote 22

Immigration contributes to the Canadian economy:

- Immigrants are present in almost all types of jobs, and their proportional representation in natural and applied sciences and related occupations, as well as in the health sector, is relatively high compared to their overall share of workers.Footnote 23

- Temporary and permanent residents are able to meet specific labour market needs in Canada. In some industrial sectors, relatively high proportions of the work force are immigrants and temporary residents.Footnote 24

- Permanent residents who become entrepreneurs in Canada contribute to economic growth by creating jobs, attracting investment to Canada, and driving innovation.Footnote 25

- According to the Conference Board of Canada, immigration will account for 100% of labour force growth over the next five years.Footnote 26

Demographic changes during the pandemic highlighted the importance of immigration to Canada. Over the past five years, immigration has accounted for over three quarters of Canada’s total population growth, but that figure dropped to 58% in 2020, due to border closures and other impacts of the pandemic.Footnote 27 As of January 2021, Canada’s population reached 38,048,738, a 0.1% increase from the previous quarter, marking the lowest annual growth since 1945 (in numbers) and 1916 (in percentage), both periods during which Canada was at war.Footnote 28 In 2020, Canada also hit a record high number of deaths recorded in a single year, reporting over 300,000 deaths.Footnote 29 Birth rates remained at 1.47, lower than the replacement rate of 2.1.Footnote 30

The impact of the pandemic resulted in a shortfall of over 156,000 permanent resident admissions in 2020. As part of efforts to address the reduced volume of applicants in 2020, IRCC increased permanent resident targets, with even distribution across the 2021-2023 Multi-Year Levels Plan. Likewise, Canada’s 2022-2024 Multi-Year Immigration Levels Plan will play a key role in supporting Canada’s post-COVID‑19 recovery. With a focus on immediate short-term economic recovery, while supporting long-term population and economic objectives, the 2022-2024 Multi-Year Immigration Levels Plan will welcome newcomers to fill labour market gaps, address regional needs, support resiliency, and foster post-COVID growth. Furthermore, the Levels Plan will continue to support the reunification of families and populations experiencing heightened vulnerabilities. This approach allows Canada to deliver on international and humanitarian obligations, while ensuring a well-managed system and the safety and security of Canadians.

To support the Multi-Year Immigration Levels Plan and Canada’s immigration priorities moving forward, IRCC will continue to work with provinces and territories, and other partners and stakeholders, to ensure that our approach to immigration continues to build prosperity and contribute to Canada’s economic recovery after the pandemic.

In addition to working with partners to meet Levels Plan targets, IRCC will continue to invest in economic immigration programs and pilots, such as the Atlantic Immigration Pilot, the Rural and Northern Immigration Pilot, the Agri-Food Pilot, the Provincial Nominee Program, the Economic Mobility Pathways Pilot, and the forthcoming Municipal Nominee Program. These initiatives are tailored to attract a broad range of talented people to the country, contribute to the development of communities, fill specific labour market needs, and help support post-pandemic recovery.

In summary, the COVID‑19 pandemic has clearly highlighted the importance of immigration to Canada. With pandemic restrictions and border closures, immigration levels decreased. At the same time, permanent and temporary residents contributed to Canada’s economy during the COVID‑19 pandemic, including those who worked in essential service positions. Moving forward, a strong immigration strategy will be essential for Canada’s post-COVID‑19 recovery.

Temporary resident programs and volumes

Temporary residents

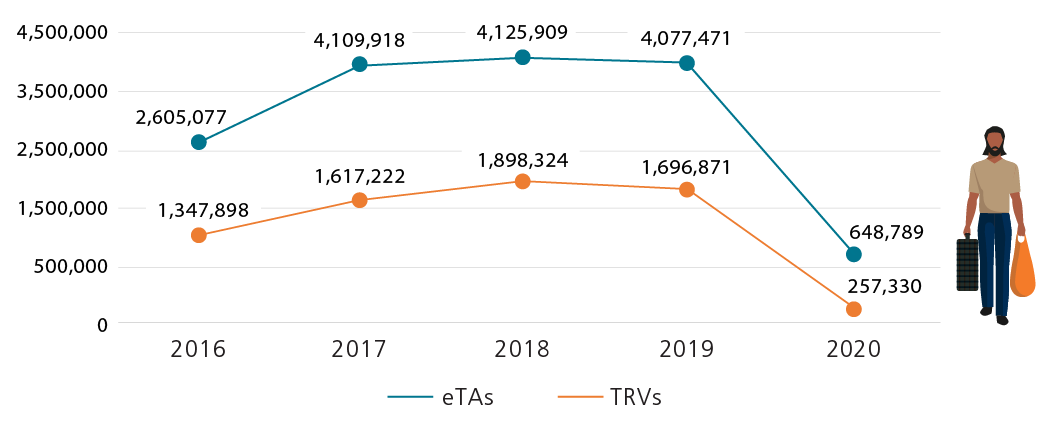

Temporary residents coming to Canada must receive either a temporary resident visa (TRV) or an electronic travel authorization (eTA) from Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) before departure to Canada, with few exceptions (notably U.S. passport holders). They include visitors, students and temporary foreign workers.

In 2020, 648,789 eTAs and 257,330 TRVs were delivered. This record low volume of documents is largely due to border closures and travel restrictions.

Temporary residents

Text version: Temporary residents

| Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eTAs | 2,605,077 | 4,109,918 | 4,125,909 | 4,077,471 | 648,789 |

| TRVs | 1,347,898 | 1,617,222 | 1,898,324 | 1,696,871 | 257,330 |

Visitors

Visitors to Canada includes tourists, business travellers, and other temporary visitors. In 2020, a total of 808,631 TRVs and eTAs were issued to visitors only. During the pandemic, IRCC supported applicants seeking to visit Canada for the purposes of family reunification by prioritizing the processing of visa and electronic travel authorizations for clients who self-identified as meeting a family member exemption, and pre-adjudicated family members who required written authorization to travel to Canada.

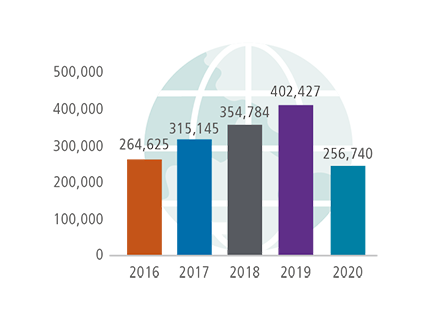

International students

International students make a significant contribution to the Canadian economy, with some estimating they contribute over $20 billion annually to Canada’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).Footnote 31 IRCC facilitates the entry of students who wish to study at a Canadian Designated Learning Institution (DLI), a designation provided by the provinces and territories. Students approved to study in Canada are issued a study permit. Prior to the COVID‑19 global pandemic, Canada continued to see strong, steady growth with an increasing number of study permit holders over time. During COVID‑19, efforts were put in place, in partnership with provinces/territories and key stakeholders, to allow students to continue their studies from abroad, due to border closures.

As of October 2020, the border measures were lifted for international students to allow them to continue their studies in Canada. Students entering Canada were required to attend a DLI with a COVID‑19 readiness plan approved by the province or territory. This regime was developed in close collaboration between IRCC, the Public Health Agency of Canada and the provinces and territories. A two-stage processing system was also put in place to facilitate applications for international students over the course of the pandemic.

In 2020, there was a total of 256,740 permit holders, a decrease of 36% compared to the total of 402,427 permit holders in 2019. International students sometimes transition towards permanent residency. In 2020, 7,755 study permit holders were granted permanent residency. This represents a 33% decrease from 2019, where 11,566 study permit holders were granted permanent residency.

Spotlight: International Education Strategy (2019-2024)

The International Education Strategy (IES) is a multi-departmental initiative involving a partnership of Global Affairs Canada, Employment and Social Development Canada, and IRCC, which was originally launched in 2014. The current IES covers the period of 2019–2024 and has a budget of $147.9 million over five years followed by $8 million per year of ongoing funding. It sets out the following three major objectives:

- Encourage Canadian students to gain new skills through study and work abroad opportunities in key global markets.

- Diversify the countries from which international students come to Canada, as well as their fields, levels of study, and location of study within Canada.

- Increase support for Canadian education sector institutions to help grow their export services and explore new opportunities abroad.

International Students

Text version: International Students

| Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student permit holders | 264,625 | 315,145 | 354,784 | 402,427 | 256,740 |

An essential part of Canada’s long-standing global attractiveness is its International Student Program. While in Canada, international students bring benefits such as new cultures, ideas, and competencies to our landscape, and also enrich the academic experience of domestic students. Some students choose to immigrate to Canada and build their careers here, thereby contributing to Canada’s economic success through their education.

In 2020, there was a total of 256,740 study permit holders. This is a 36% decrease compared to the previous year, largely as a result of the effects of the pandemic on travel and access to services to submit required documentation for a complete application.

Temporary Foreign Workers

IRCC facilitates the entry of foreign nationals who seek temporary work in Canada. In 2020, IRCC worked closely with other government departments – including Employment and Social Development Canada, the Public Health Agency of Canada and the Canada Border Service Agency – to facilitate the safe arrival of temporary workers from overseas, despite border restrictions, in recognition of the critical role they play in certain in-demand occupations like health care, agriculture, food, and seafood production.

Temporary Foreign Workers (TFWs) bring essential skills to Canadian businesses. Over the course of the pandemic, the importance of TFWs to Canada was highlighted as many filled essential service jobs, particularly in the agriculture sector.

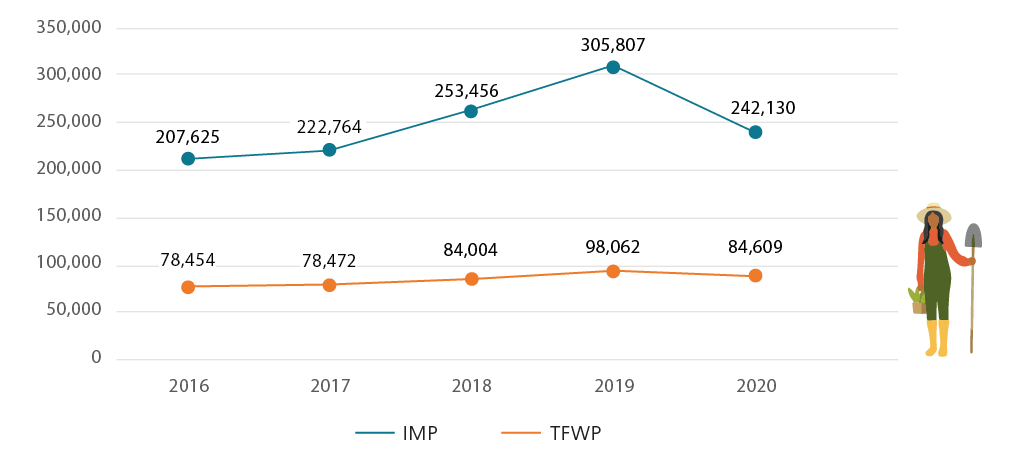

As per the graph below on the TFW Program and International Mobility Program (IMP), volumes showed a steady increase from 2016–19 for both programs, and a decrease in 2020 as a result of the pandemic. In 2020, there were a total of 84,609 permit holders through the TFW Program, which represents a decrease of 14% compared to the 98,062 permit holders in 2019. Under the IMP, there were a total of 242,130 work permit holders in 2020, representing a decrease of 21% compared to a total of 305,807 work permit holders in 2019. Furthermore, the International Experience Canada program – one of the largest programs under the IMP – also recorded a decline in the number of work permit holders, from 61,638 in 2019 to 18,725 in 2020, representing a 70% decrease.

Temporary Foreign Workers

Text version: Temporary Foreign Workers

| Year | TFWP | IMP |

|---|---|---|

| 2016 | 78,454 | 207,625 |

| 2017 | 78,472 | 222,764 |

| 2018 | 84,004 | 253,456 |

| 2019 | 98,062 | 305,807 |

| 2020 | 84,609 | 242,130 |

Permanent immigration to Canada

Economic immigration

GBA Plus Spotlight

Gender disaggregation of data concerning the total number of admissions (principal applicant and their immediate family unit) within each economic immigration program shows near parity between women and men. For instance, in 2020, a total of 50,294 women and 56,127 men were admitted through the economic class.

The economic immigration class is the largest source of permanent resident admissions to Canada, at approximately 58% of all admissions in 2020, which is consistent with the trend observed over the past four years.

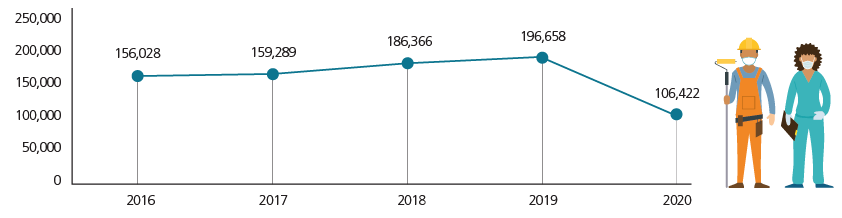

In 2020, the number of individuals admitted to Canada under the economic class totaled 106,422, representing a decrease of 46% from 2019. In 2019, Canada admitted 196,658 individuals in this class.

The economic class of immigrants is a critical component for meeting labour gaps in Canada. Through the economic class, Canada seeks highly skilled workers, as well as those who meet current economic needs, with the opportunity to apply through a fair and responsive program. Overall, economic immigration programs and pilots experienced disruption in 2020 due to impacts of the COVID‑19 pandemic. Significant continued interest in economic immigration to Canada (along with an ease in travel restrictions), promotional efforts, and new initiatives such as the temporary pathway to permanent residence for essential temporary workers and recent international graduates, are expected to contribute to the achievement of annual admissions targets moving forward.

Economic immigrationTable note *

Text version: Economic immigration

| Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Economic immigration | 156,028 | 159,289 | 186,366 | 196,658 | 106,422 |

Family reunification

Canadian permanent residents and citizens may sponsor members of their familyFootnote 32 to come to Canada as permanent residents, which brings many economic, social and cultural benefits to communities across Canada. Sponsors accept financial responsibility for the individual for a defined period of time.

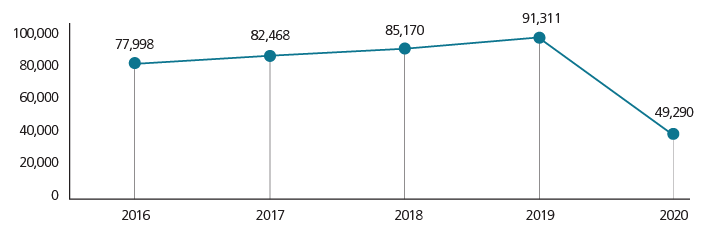

In 2020, 49,290 individuals were admitted under this category, compared to 91,311 in 2019. Recognizing the importance of bringing families together, especially during challenging times, the Department made significant efforts to process permanent residence applications made under the Family Reunification Program in 2020. Measures included digitizing paper-based applications to facilitate processing by staff working remotely. In addition, the Government has worked to reunite families by amending the Entry Orders-in-Council implemented under the Quarantine Act in response to the COVID‑19 pandemic several times. For immediate family members, the requirement to be traveling for a non-discretionary purpose was lifted in June 2020 as long as the family member was travelling to Canada for 15 or more days. In October 2020, the Orders were amended further to permit the entry of extended family members given the undue burden that the length of the pandemic presented for these family relationships.

Family reunification

Text version: Family reunification

| Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family reunification | 77,998 | 82,468 | 85,170 | 91,311 | 49,290 |

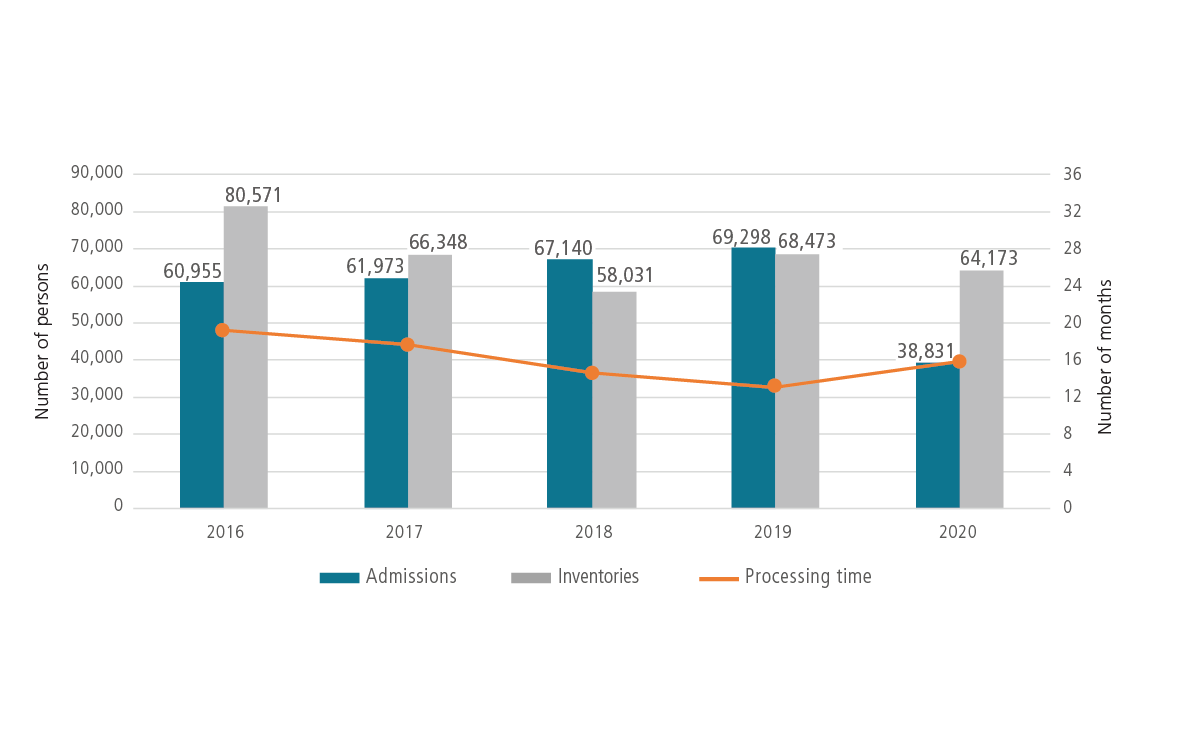

Spouses, partners and children

As part of the Family Reunification Program, there is a dedicated focus on processing applications for spouses, partners and children of Canadian citizens, and permanent residents. In 2020, there were 38,831 admissionsFootnote 33 processed under this category, with a remaining inventory of 64,173 at the end of the year. Due to COVID‑19, applications for spouses, partners and children had a processing time of 16 months in 2020, compared to 14 months in 2019. The Department has since implemented additional solutions aimed at processing new applications within the 12 months service standard.Footnote 34 These measures include file digitization, remote processing of applications, conducting remote interviews, the use of Advanced Analytics, the introduction of an online application portal for clients and representatives and an increased number of decision makers assigned to family class applications.

Spouses, Partners and Children

Text version: Spouses, Partners and Children

| Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processing time | 19 | 18 | 14 | 13 | 16 |

| Admission | 60,955 | 61,973 | 67,140 | 69,298 | 38,831 |

| Inventories | 80,571 | 66,348 | 58,031 | 68,473 | 64,173 |

Parents and grandparents

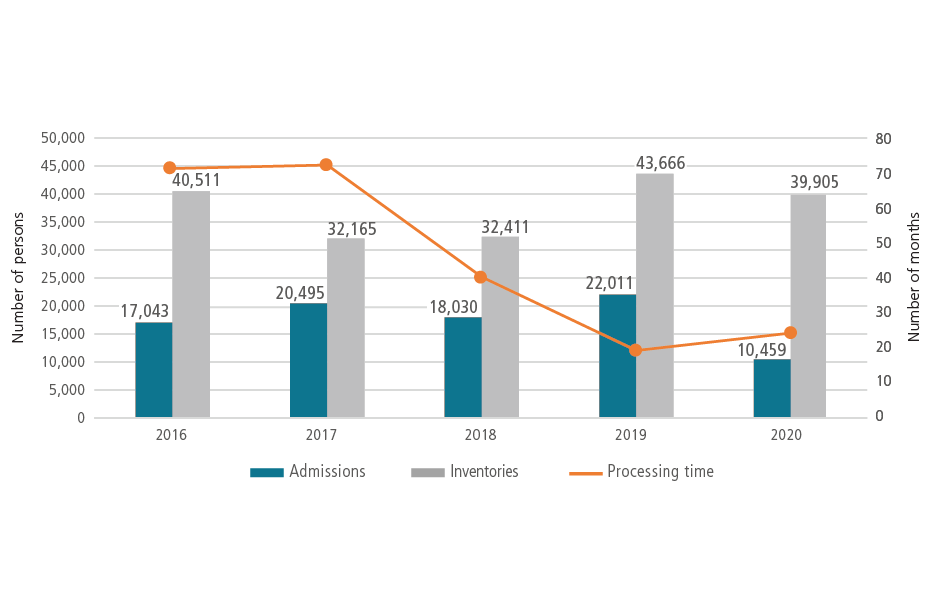

In 2020, also as part of family reunification, 10,459 sponsored parents and grandparents were admitted as permanent residents to Canada. Parent and grandparent applications were processed within 24 months. The increase in the delay compared to 2019’s processing time (19 months) is explained by the impact that COVID‑19 had on Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) operations. The Department will continue to address the backlog caused by the COVID‑19 pandemic and to focus efforts on returning to pre-COVID‑19 processing times.

Parents and Grandparents

Text version: Parents and Grandparents

| Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processing time | 71 | 72 | 40 | 19 | 24 |

| Admission | 17,043 | 20,495 | 18,030 | 22,011 | 10,459 |

| Inventories | 40,511 | 32,165 | 32,411 | 43,666 | 39,905 |

The launch of the 2020 Parents and Grandparents Program was delayed to allow the Government of Canada to prioritize its efforts to contribute to the whole-of-government response due to the pandemic.Footnote 35 Recognizing the importance of keeping families together, IRCC successfully launched the annual application intake for the Parents and Grandparents Program in October 2020.Footnote 36 A random selection process was introduced to ensure that all interested sponsors had an equal opportunity to be selected and that the process was fair, transparent, and accessible. In response to economic challenges exacerbated by the COVID‑19 pandemic, the Department also introduced facilitative measures to ease the income eligibility requirement for the 2020 tax year for those sponsoring their parents or grandparents.

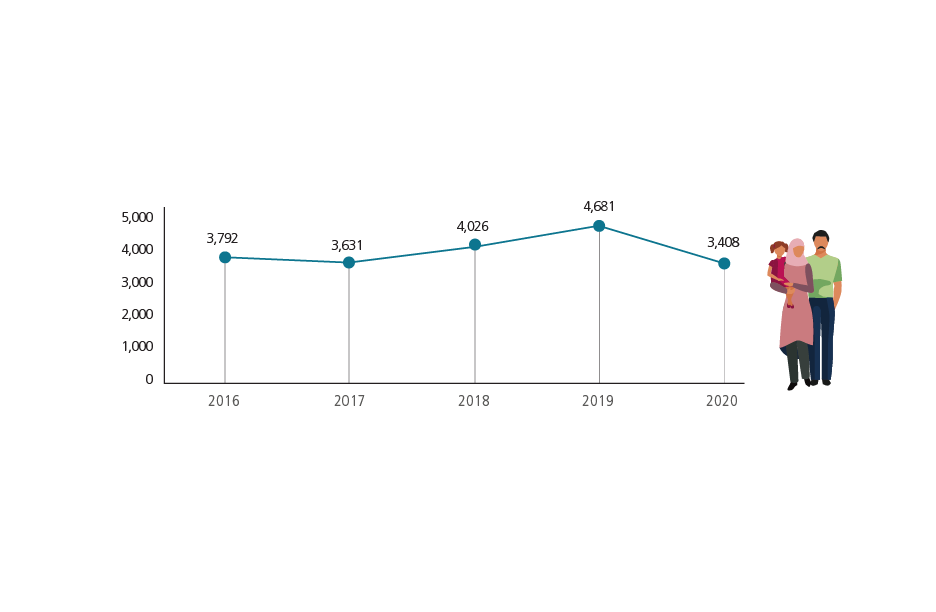

Humanitarian and compassionate immigration

Permanent residency may be granted in exceptional circumstances based on humanitarian and compassionate grounds or public policy considerations. In 2020, there were 3,408 permanent residents admitted through these discretionary streams, which is a 27% decrease compared to 2019 where there were 4,681 admissions.

Humanitarian and Compassionate

Text version: Humanitarian and Compassionate

| Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Humanitarian and Compassionate | 3,792 | 3,631 | 4,026 | 4,681 | 3,408 |

In January 2020, IRCC implemented a temporary public policy to further facilitate access to permanent resident status for out-of-status construction workers in the Greater Toronto Area (GTA) that provided a pathway to permanent resident status for up to 500 out-of-status construction workers in the Greater Toronto Area. These workers have continued to address significant labour shortages in the construction industry, while also contributing to their communities and the broader economy.

In December 2020, IRCC implemented a temporary public policy to facilitate the granting of permanent residence for certain refugee claimants working in the health care sector and providing direct patient care during the COVID‑19 pandemic. This one-time initiative recognized the service of those who were working in the health care sector, where there was an urgent need for help.

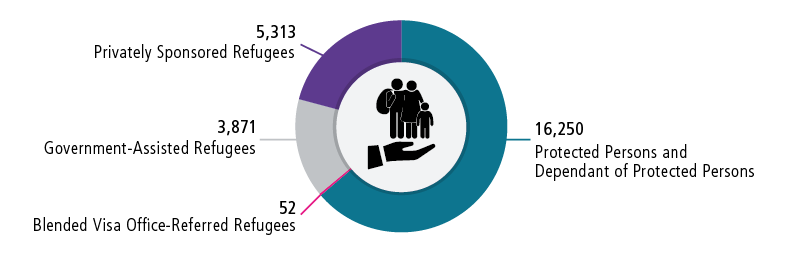

Refugees and Protected Persons

Text version: Refugees and Protected Persons

| Protected Persons and Dependant of Protected Persons | 16,250 |

|---|---|

| Blended Visa Office-Referred Refugees | 52 |

| Government-Assisted Refugees | 3,871 |

| Privately Sponsored Refugees | 5,313 |

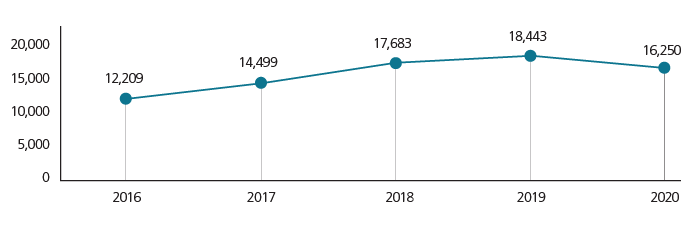

Protected Persons

IRCC provides support to protected persons and their dependants. A person who has reason to fear persecution in his or her country of origin due to race, religion, nationality, membership in a social group, or political opinion can be designated as a protected person by the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada and IRCC.

Protected persons in-Canada may apply for permanent residence in Canada and include in the application their dependants who are in Canada and abroad. Protected persons in-Canada include:

- convention refugees

- persons in need of protection determined by the Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada

- people with positive pre-removal risk assessments

- protected temporary residents

In 2020, 16,250 individuals obtained permanent residence under the protected persons in-Canada and dependants abroad category. This represents a 12% decrease compared to the 18,443 individuals who obtained permanent residence in 2019.

Protected persons and dependant of protected persons

Text version: Protected persons and dependant of protected persons

| Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protected Persons and Dependant of Protected Persons | 12,209 | 14,499 | 17,683 | 18,443 | 16,250 |

Resettled Refugees

Each year, IRCC facilitates the admission of a targeted number of permanent residents under the refugee resettlement category. These are persons who are outside of their home country and are unable to return based on a well-founded fear of persecution due to race, religion, nationality, or membership in a particular social group or association with a political opinion, as well as those who are outside their home country and have been seriously affected by civil war or armed conflict, or those who have been denied basic human rights on an ongoing basis.

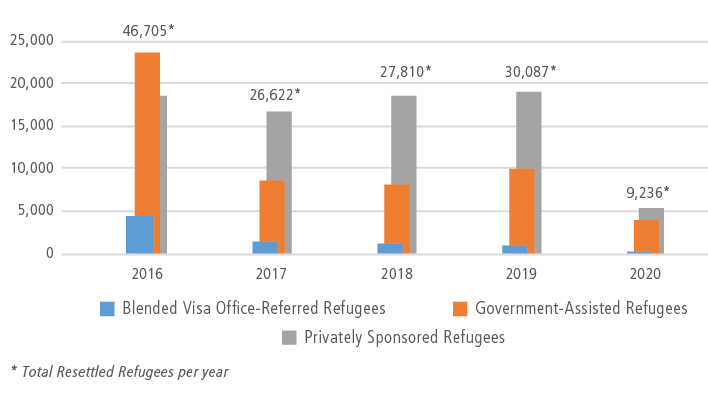

According to the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), Canada was among the top three countries in the world to welcome resettled refugees in 2020.Footnote 37 In 2020, a total of 9,236 resettled refugees were admitted to Canada, which is a decrease of 69% when compared to the 30,087 resettled refugees admitted to Canada in 2019. This decrease is mainly attributable to COVID-related border closures and other pandemic restrictions. In 2020, IRCC also funded 34 resettlement assistance service provider organizations in Canada who supported over 8,000 refugees across the country.

While the pandemic had significant impacts on refugee resettlement in Canada, IRCC responded with the extension of coverage through the Interim Federal Health Program, by working with the Refugee Sponsorship Training Program to provide necessary support and information to refugee newcomers, and by ensuring necessary COVID‑19 public health and safety measures were in place for those who were able to travel to Canada.

In addition, IRCC worked to build the foundation for a new refugee stream dedicated to human rights defenders at risk. Broad consultations involved international experts and Canadian organizations to ensure that the program design best meets the needs of the human rights defenders. Human rights defenders will be identified and referred by international experts in collaboration with the United Nations Refugee Agency, and will be resettled through the Government-Assisted Refugees Program. Like other government-assisted refugees, they will be supported upon arrival in Canada by settlement provider organizations funded by IRCC.

Resettled Refugees

Text version: Resettled Refugees

| Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blended Visa Office-Referred Refugees | 4,435 | 1,285 | 1,149 | 993 | 52 |

| Government-Assisted Refugees | 23,628 | 8,638 | 8,093 | 9,951 | 3,871 |

| Privately Sponsored Refugees | 18,642 | 16,699 | 18,568 | 19,143 | 5,313 |

Asylum Claims

The in-Canada asylum system provides protection to foreign nationals when it is determined that they have a well-founded fear of persecution.

Over the course of the pandemic, Canada continued to receive asylum claims at inland offices (via email) made by foreign nationals already in Canada, and at land ports of entry, where the Safe Third Country Agreement regime and its exceptions remain in effect. A number of eligibility decisions were delayed due to operational restrictions linked to COVID‑19. This accumulated inventory is being addressed as a priority, including through the use of innovative approaches such as the piloting of virtual Minister’s Delegate Reviews.Footnote 38

Canada received approximately 24,000 asylum claims in 2020. Of these, approximately 14% were made by asylum claimants who crossed the Canada-U.S. border between designated ports of entry.Footnote 39 This represents a 63% decrease compared to the 64,040 claims made in 2019. Planning throughout the COVID‑19 pandemic has ensured that the asylum system will be able to effectively manage a rebound in volumes and potential surges once border closures and travel restrictions are lifted.

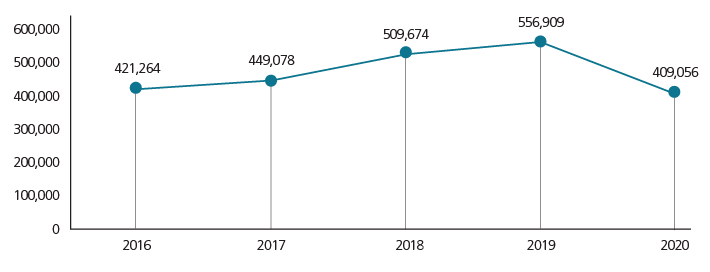

Settlement and Integration

IRCC supports the successful integration of immigrants to Canada through a suite of settlement and integration services. In 2020, IRCC funded more than 500 service provider organizations, and provided settlement services to more than 409,000 clients.

Over the course of the pandemic, the majority of settlement services, including language training, were shifted to online delivery, to ensure that newcomers and refugees continued to be supported while respecting public health guidelines. IRCC also introduced flexibilities in funding agreements at the start of the pandemic to allow the extensive network of service providers to successfully pivot and to ensure continuity of services. From 2019 to 2020, there was a decrease of 27% in permanent residents who received at least one settlement service, in alignment with lower arrivals due to COVID‑19.

Clients who received at least one Settlement Service

Text version: Clients who received at least one Settlement Service

| Year | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clients who received at least one Settlement Service | 421,264 | 449,078 | 509,674 | 556,909 | 409,056 |

Francophone immigration outside of Quebec

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) continues to support the commitment of the Government of Canada to enhance the vitality of French linguistic minority communities in Canada outside of Quebec. Francophone immigration plays an important role in upholding the bilingual nature of the country, and supporting the growth of French linguistic minority communities and Canada’s economic recovery.

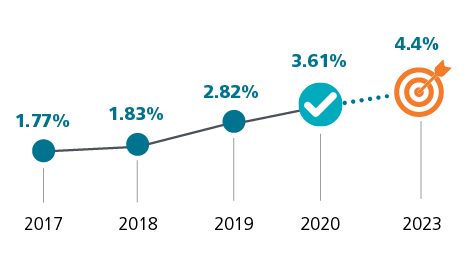

IRCC’s Francophone Immigration Strategy has three objectives, including to increase Francophone immigration to reach a target of 4.4% of French-speaking immigrants outside of Quebec by 2023. In 2020, efforts in support of this objective relied on actions across the five pillars of the immigration continuum as laid out in the Strategy, from attraction to selection and retention of French-speaking newcomers outside of Quebec. Key initiatives included: strengthened selection tools favouring French-speaking candidates; targeted promotional efforts in Canada and abroad; continued consolidation of Francophone settlement and resettlement services; and ongoing collaboration with provinces and territories.

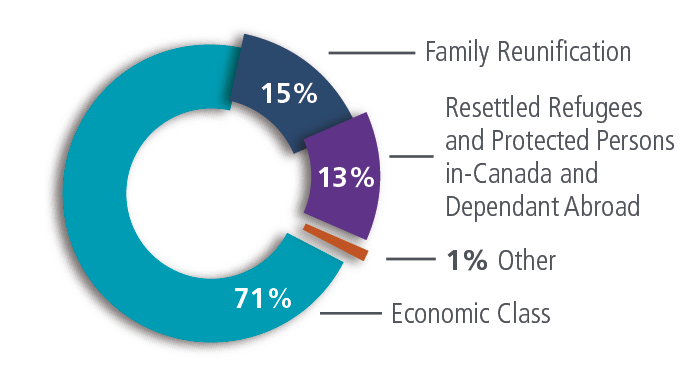

These efforts resulted in 5,756 French-speaking permanent residents admitted to Canada outside of Quebec in 2020, which is an increase over previous years and represents 3.61% of all permanent residents admitted to Canada outside Quebec. Of these, 71% came through the Economic class, which includes federal and provincial economic programs, and more than 50% were citizens of France, Morocco and Algeria.

Percentage of admissions of French-speaking permanent residents outside Quebec

Text version: Percentage of admissions of French-speaking permanent residents outside Quebec

| Year | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Plan for 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of admissions of French-speaking permanent residents outside Quebec | 1.77% | 1.83% | 2.82% | 3.61% | 4.4% |

French-speaking Permanent residents Admitted outside Quebec

Text version: French-speaking Permanent residents Admitted outside Quebec

| Economic Class | 71% |

|---|---|

| Family Reunification | 15% |

| Resettled Refugee and Protected Person in-Canada and Dependant Abroad | 13% |

| Other | 1% |

Spotlight: Leveraging Express Entry in Support of Francophone Immigration

IRCC has focused on the selection of highly qualified French-speaking immigrants who can meet labour market needs, support the vitality of French linguistic minority communities and contribute to Canada’s economic recovery. In 2020, the Department increased the additional points awarded to French-speaking and bilingual candidates under the Express Entry system, which has become a key driver of French-speaking admissions to Canada. Fifty-eight percent of French-speaking economic admissions in 2020 came through Express Entry, and their share of invitations to apply for permanent residence under Express Entry reached 5.2% for the year.

Promotion of Francophone immigration

The Department strategically pursued promotional activities targeting the large pools of qualified French-speaking foreign nationals across the globe and within Canada in order to attract and recruit them to Canada and to retain them. During 2020, IRCC organized over 230 events abroad, which were mainly virtual information sessions and webinars due to the pandemic. IRCC also delivered over 810 outreach activities in Canada where Francophone immigration tools and policies were promoted to key stakeholders, such as international students, Canadian employers and minority language community groups. In the Fall of 2020, in partnership with the Réseau de développement économique et d’employabilité, IRCC held the annual Tournée de Liaison virtually to discuss the impact of the pandemic on the employment situation of Francophone immigrants outside of Quebec in communities and how immigration can support economic recovery. The Tournée de Liaison included a virtual B2B Fair, bringing together Canadian employers, representatives from 10 IRCC offices overseas, 12 employment agencies of partner countries, and nine provinces and territories.

Francophone settlement services

Several initiatives funded through the Action Plan for Official Languages 2018–2023 support the Francophone Integration Pathway, which consists of a suite of settlement services in French, offered in a coordinated and integrated manner by Francophone communities outside of Quebec to French-speaking newcomers. The Francophone Integration Pathway has established the groundwork for an effective service infrastructure so French linguistic minority communities are better able to welcome, integrate, and retain newcomers.

Welcoming Francophone Communities Initiative

Since April 2020, 14 selected communities have received $4.2 million per year over three years (2020 to 2023) through the Welcoming Francophone Communities initiative for community-based projects to help French-speaking newcomers settle in their host communities.

Strengthening the Francophone settlement sector’s capacity

In April 2020, IRCC launched the Comité consultatif national en établissement francophone, whose mandate is to provide recommendations on a renewed national coordination of the Francophone settlement sector and to inform future policies and programs. In addition, eight organizations are being funded to implement projects to strengthen the capacity of Francophone minority communities and settlement workers in areas such as mental health, justice, and support for seniors, women and families, and employer engagement in French.

Language training adapted to the needs of French-speaking newcomers

IRCC has continued to fund language training services adapted to the needs of French-speaking newcomers settling in Francophone minority communities to help them develop the skills they need for work and to settle in their communities, in both of Canada’s official languages. The funding also includes enhancing the capacity of service provider organizations to deliver second language training in French.

Federal-Provincial/Territorial Collaboration for Francophone Immigration

IRCC continues to work with provinces and territories to advance cross-jurisdictional efforts in support of its Strategy for Francophone Immigration. In 2020, the Provincial Nominee Program was the second largest driver to attract French-speaking economic immigrants to Canada, with admissions under this program representing almost 41% of economic admissions outside of Quebec overall.

In addition, the Federal-Provincial/Territorial (FPT) Forum of Ministers Responsible for Immigration continued to work together to identify activities that all jurisdictions can implement collectively based on the FPT Action Plan for Francophone Immigration Outside of Quebec.

International engagement

Canada’s international leadership on migration and refugee protection

In 2020, Canada continued to provide guidance and leadership on global migration and refugee protection issues as we recognized the significant impact of the COVID‑19 pandemic on migrants and refugees around the world. Canada engaged bilaterally with other countries, and multilaterally with international partners and organizations, to collaborate on a range of migration and refugee protection issues. For example, at the conclusion of Canada’s 2019–20 Chair of the Annual Tripartite Consultations on Resettlement (ATCR), Canada announced the admission of up to 500 refugees as part of the Economic Mobility Pathways Project over the next two years, and the establishment of an advisory role for a former refugee on Canadian delegations to certain international refugee protection system meetings such as those of the United Nations Refugee Agency’s Executive Committee and the ATCR. As a champion of both the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration, and the Global Compact on Refugees, Canada’s international engagement has also continued to support migration and asylum capacity-building initiatives, and the development of refugee solutions, including resettlement and complementary pathways.

Immigration measures for Hong Kong

Following China’s imposition of a National Security Law on Hong Kong in June 2020, and concerns about the deterioration of right and freedoms, Canada committed to taking action and standing up for the people of Hong Kong.

In November 2020, the Department announced a number of special measures to help Hong Kong residents come to Canada, including a new temporary residence option for Hong Kong residents that provides open work permits of up to three years to those who have obtained recent post-secondary education experience in Canada or abroad.

Canada’s next permanent resident Immigration Levels Plan

The Multi-Year Immigration Levels Plan determines how many permanent residents Canada aims to admit over the course of a calendar year. Every year, Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada sets targets and ranges for the total number of permanent residents admitted into the country, as well as the number for each immigration category.

IRCC has presented a rolling multi‑year (3 years) Immigration Levels Plan for admissions every year since 2017. The plan is developed in consultation with provinces and territories, stakeholder organizations and the public. Selection of applicants is categorized based on: economic contributions; family reunification; or support for refugees, protected persons and humanitarian and compassionate needs. The 2022‑2024 Immigration Levels Plan has been developed considering the evolving situation of COVID‑19 and its implications for permanent resident admissions.

| 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Projected admissions – Targets | 431,645 | 447,055 | 451,000 | |||

| Projected admissions – Ranges | Low | High | Low | High | Low | High |

| Economic immigrationTable note * | 210,000 | 248,000 | 222,000 | 259,000 | 235,000 | 273,000 |

| Family reunification | 90,000 | 109,000 | 94,000 | 113,000 | 99,000 | 117,000 |

| Refugees, protected persons, humanitarian and compassionate and other | 60,000 | 88,000 | 64,000 | 93,000 | 56,000 | 85,000 |

| TotalTable note ** | 360,000 | 445,000 | 380,000 | 465,000 | 390,000 | 475,000 |

Gender-Based Analysis Plus

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) is required under the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act to include a Gender-Based Analysis (GBA) Plus assessment of the impact of the Act in its Annual Report. This year’s report features GBA Plus spotlights throughout the document, in addition to the section below on IRCC’s implementation of GBA Plus initiatives.

GBA Plus is a tool for understanding how multiple factors, such as race, ethnicity, gender, religion, disability, sexual orientation, education, income, language, Indigeneity, and age, shape health, social, and economic outcomes for people, as well as influence access to programs and services. It is used in the design and implementation of policies, programs and other initiatives so that they are more inclusive and responsive to the different needs of people. IRCC remains committed to working towards the full implementation of GBA Plus throughout its business lines to ensure that its initiatives are developed with equality, diversity and inclusion in mind.

Internationally, IRCC applies GBA Plus to promote inclusive and participatory engagement abroad. The Department is working at the bilateral and multilateral levels to encourage dialogue and collaboration on migration management and refugee protection that is more gender-responsive and inclusive of a variety of identity factors for diverse newcomers.

In 2020, IRCC also launched the Anti-Racism Task Force to advance racial equity in the Department.

Anti-Racism Task Force

Anti-Racism Task Force

Departmental Antiracism Task Force was created to:

- Identify Racism

- Recommend strategies to go about tackling it

- Set metric for success

- Build capacity within the department to address race-related issues through awareness and education

The Task Force works collaboratively with all branches within the organization to combat systemic racism internally and in our client-facing policies and service delivery. While the focus in 2020 was on internal people management initiatives including assessing the impacts of systemic racism on employees and anti-racism learning initiatives, the competency and capacity developed on this issue is expected to start being reflected in our external, client-facing policies in 2021 and onwards. The goal is to support a more equitable and inclusive organization.

In 2020, IRCC made progress on several GBA Plus initiatives that were put in place during or before 2019.

GBA Plus Highlights at IRCC

Text version: GBA Plus Highlights at IRCC

GBA Plus Highlights at IRCC

- Improving outcomes for LGBT2 populations

- Creating initiatives to support survivors and those at risk of gender-based violence

- Facilitating resettlement and economic mobility in Canada

- Supporting racialized newcomers

- Advocating for gender and diversity on the international stage

Improving outcomes for LGBTQ2 populations

The Rainbow Refugee Assistance Partnership

Established in 2020, the Rainbow Refugee Assistance Partnership built on the success of the Rainbow Refugee Assistance Pilot by increasing the number of privately sponsored refugees from 15 to 50 per year. The Partnership was established in cooperation with the Rainbow Refugee Society, with the aim of encouraging more Canadians to support LGBTQ2 refugees and strengthening collaboration between LGBTQ2 organizations and the refugee settlement community in Canada.Footnote 40 In 2020, there were only eight landings of refugees through this partnership due to COVID‑19 travel restrictions.

IRCC’s Sex and Gender Client Identifier Policy

In alignment with the Treasury Board Secretariat Policy Direction to Modernize the Government of Canada’s Sex and Gender Information Practices, IRCC established a Departmental Sex and Gender Client Identifier Policy in 2020. The Policy sets out how a client’s sex or gender information should be collected, recorded, and displayed in the administration of all IRCC programs. As a result of past efforts under the Gender X Project, significant work to implement the Policy has already taken place. For example, all IRCC lines of business allow clients to request a non-intrusive change of their sex or gender identifier, including Female (“F”), Male (“M”), and Another Gender (“X”) on any IRCC-issued document. Moving forward, IRCC will suppress the display of this information on documents and correspondence where there is no substantiated need to do so.

Creating initiatives to support survivors and those at risk of gender-based violence

Gender-Based Violence Strategy

In June 2017, the Government of Canada announced It’s Time: Canada’s Strategy to Prevent and Address Gender-Based Violence, the federal response to gender-based violence. The initiative focuses on three main areas of action: prevention, support for survivors and their families, and the promotion of responsive legal and justice systems. Under this federal strategy, IRCC received $1.5 million in funding over five years (2017‑22) to further enhance the Settlement Program, which delivers pre- and post-arrival settlement services to newcomers to Canada. The funding is being used to develop and implement a settlement sector strategy on gender-based violence through a coordinated partnership of settlement and anti-violence sector organizations. In response to the increase in gender-based violence in the pandemic context, IRCC consulted with service provider organizations to better understand the situation for newcomers. As a result, IRCC issued guidance and information to organizations on the continuation of services considered essential, which included providing support to clients experiencing gender-based violence.

Canada’s Assistance to Women at Risk Program

The Canada’s Assistance to Women at Risk Program is designed to offer resettlement opportunities to women who are at increased risk of discrimination and violence, including those who are in precarious situations where local authorities cannot ensure their safety. Some women may need immediate protection in the short-term, while others are in permanently dangerous circumstances. Gender-based persecution is one of the grounds upon which Canada grants refugee protection. In 2020, Canada resettled 564 vulnerable refugee women and children through this program.

Measures to support newcomers to leave situations of family violence

Measures to support newcomers to leave situations of family violence were introduced in 2019 and continued throughout 2020 to help individuals escape abuse. These measures included:

- An expedited, fee-exempt, temporary resident permit for individuals who lack status, which also gives individuals a work permit and health care coverage. In 2020, 109 permits were issued under this initiative.

- An expedited process to apply for permanent residence on humanitarian and compassionate grounds. In 2020, 66 positive eligibility decisions were made under this process.

Facilitating resettlement and economic mobility in Canada

Resettlement Assistance Program

The Resettlement Assistance Program, a national Grants and Contribution program created in 1998 that operates in all provinces with the exception of Quebec, helps government-assisted refugees (GARs) and other eligible clients when they first arrive in Canada. The program provides direct financial support and funds the provision of immediate and essential services. In 2020, IRCC began a review of services and service delivery for GARs, taking a close look at the Resettlement Assistance Program and settlement services accessed by GARS during their first year in Canada. The goal of this policy and research project is to identify opportunities for program improvement.

Economic Mobility Pathways Pilot

The Economic Mobility Pathways Pilot (EMPP) is Canada’s model for refugee labour mobility. The pilot was launched in April 2018 as a feasibility study to provide evidence on the ability of refugees to access Canada’s economic immigration programs and to document the challenges they face in doing so. In 2020, the Department committed to admitting up to 500 refugees as part of the EMPP Pilot over the next 2 years.Footnote 41

Supporting racialized newcomers

Racialized Newcomer Women Pilot

Programming under the Racialized Newcomer Women Pilot (formerly the Visible Minority Newcomer Women Pilot) is designed to support employment outcomes and career advancement for racialized newcomer women through the delivery of settlement services. Extensions were provided to select agreements to 11 projects, originally anticipated to end in March 2021, that were best suited to continue direct service delivery to support racialized newcomer women as the economy recovers. Additionally, the Social Research and Demonstration Corporation, which is testing four specific employment models targeting racialized newcomer women, received additional funding to explore the applicability of the four models for Francophone racialized newcomer women and to undertake a retrospective study of the funding provided to partners and clients. Results from the Racialized Newcomer Women Pilot will inform employment settlement services for newcomer women.

Advocating for gender and diversity on the international stage

Participation within international fora

Working with our partners, we are also increasingly taking steps to ensure diverse voices are heard across these fora. In the 2020 EU-Canada Migration Platform Event on the Integration of Migrant Women jointly organized by Canada and the European Commission, migrant women shared their expertise throughout the event and led the conversation at the concluding high-level panel with Canada and EU Minister-level participants. Such engagements help advance gender equality, and support greater inclusion and the empowerment of migrant women.

Global Compact for Migration

In 2020, Canada accepted the opportunity to become a champion country of the Global Compact for Migration. It has used this platform internationally to share best practices related to gender-responsive migration management. Canada also funded migration capacity building projects and research to support gender-responsive migration management.

In conclusion, IRCC continued to advance key GBA Plus initiatives in 2020, and will continue to promote GBA Plus initiatives that encourage diversity and inclusion within IRCC operations, as well as throughout IRCC programs.

Annex 1: Section 94 and Section 22.1 of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

The following excerpt from the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA), which came into force in 2002, outlines the requirements for Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada to prepare an annual report to Parliament on immigration.

Reports to Parliament

94 (1) The Minister must, on or before November 1 of each year or, if a House of Parliament is not then sitting, within the next 30 days on which that House is sitting after that date, table in each House of Parliament a report on the operation of this Act in the preceding calendar year.

(2) The report shall include a description of

- (a) the instructions given under section 87.3 and other activities and initiatives taken concerning the selection of foreign nationals, including measures taken in cooperation with the provinces;

- (b) in respect of Canada, the number of foreign nationals who became permanent residents, and the number projected to become permanent residents in the following year;

- (b.1) in respect of Canada, the linguistic profile of foreign nationals who became permanent residents;

- (c) in respect of each province that has entered into a federal-provincial agreement described in subsection 9(1), the number, for each class listed in the agreement, of persons that became permanent residents and that the province projects will become permanent residents there in the following year;

- (d) the number of temporary resident permits issued under section 24, categorized according to grounds of inadmissibility, if any;

- (e) the number of persons granted permanent resident status under each of subsections 25(1), 25.1(1) and 25.2(1);

- (e.1) any instructions given under subsection 30(1.2), (1.41) or (1.43) during the year in question and the date of their publication; and

- (f) a gender-based analysis of the impact of this Act.

Declaration

The following excerpt from IRPA outlines the Minister’s authority to declare when a foreign national may not become a temporary resident, which came into force in 2013, and the requirement to report on the number of such declarations.