Wildfires in Canada: Toolkit for Public Health Authorities

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 2.15 MB , 51 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Updated July 2024

Table of contents

- List of figures and tables

- Acknowledgements

- 1) Rationale

- 2) Background

- 3) Public health action and interventions

- 4) Guidance documents

- 5) Appendices

- References

List of figures and tables

- Figure 1: The emergency management continuum

- Figure 2: Wildland fire risk logic model

- Figure 3: Air Quality Health Index risk scale

- Table 1: Health messages by AQHI health risk categories

- Table 2: Provincial/Territorial guidance documents

- Table 3: International guidance documents

Acknowledgements

This product was developed by the Public Health Agency of Canada in close collaboration with Health Canada as part of the Health Portfolio response to wildfires in Canada.

Additional consultations and contributions from Environment and Climate Change Canada, Indigenous Services Canada, Natural Resources Canada, and Public Safety Canada, further supported the development of this toolkit.

With acknowledgement of our Federal, Provincial and Territorial partners including the Committee on Health and the Environment, the Public Health Emergency Management Working Group and Public Health Network Council for their review and feedback.

1) Rationale

Canada is experiencing longer wildfire seasons and more frequent and extreme fire behaviour, which has significant effects on human health and the natural environment.Footnote 1 In Canada, the wildfire season typically runs from early April to late October. In 2023, we experienced an unprecedented wildfire season, with a larger geographic extent and severity than previously recordedFootnote 2 with 2024 anticipated to be another active season. A number of factors are likely contributing to this change. Climate change is affecting the number and severity of wildfires. In addition, human behaviours and management practices have impacted the overall risk.Footnote 3

Health hazards and risks associated with wildfires range from immediate physical exposure to wildfire and smoke, to mental health impacts and longer-term health impacts, including cultural and spiritual impacts. Extreme heat events can often occur at the same time as wildfire and smoke events further compounding impacts or leading to additional health risks. Evacuations also present further unintended risks such as interrupted access to medications and medical appointments, social and support structures, and a potential rise in infectious diseases in evacuation centres due to people living in close quarters for an extended time and cleanliness. Following wildfires, an increase in mental health impacts have also been observed including insomnia, substance use, violence and depression. It is well established that these risks are not equally distributed throughout the population and specific groups may experience disproportionate risk due to underlying conditions, preexisting inequities, geographic, demographic, socio-economic status or other factors.

The role of public health authorities in wildfire response varies across Canada. In most cases, public health authorities contribute to the emergency response by providing direction, recommendations, advice and communications aimed at minimizing the associated human health hazards and risks. While some regions of Canada experience cyclical wildfire events most years, large and more intense wildfires and the associated wide-spread smoke events are requiring greater public health involvement in wildfire emergencies. This has resulted in the engagement of public health professionals with differing levels of experience and familiarity with wildfire emergency preparedness and response. With the increased profile of public health authorities as health system leaders during the COVID-19 pandemic, public health authorities at all levels of government are more engaged than ever before.

1.1) Goal and objectives

The goal of this toolkit is to summarize information and bring together existing resources to support public health authorities in the mitigation, preparedness, response and recovery to human health risks associated with wildfires. Specific objectives are to:

- Facilitate evidence-based and timely decision making by public health authorities

- Synthesize existing resources in the form of evidence-based summaries of human health hazards and risks

- Support the sharing of best practices and experiences

- Apply a public health lens to the prevention and management of human health hazards and risks across the emergency management continuum

Some of the content may also be applicable to urban fires; however, this is not the focus of this document except in the case of wildfires that spread to and through the wildland urban interface.

Recognizing that local contexts and public health systems and resources vary, the public health actions and interventions that have been summarized in this document are not meant to be directive. They are potential actions that can be adopted or adapted in different jurisdictions, contexts and situations. The resources provided are a non-exhaustive compilation of existing documents including provincial and territorial guidance documents, fact sheets, and literature. Please note the guidance provided in documents external to the Government of Canada may not reflect the views and opinions of the Government of Canada or be available in both official languages.

2) Background

2.1) Health Hazards and Risks

Wildfires, and the response to them, present a range of potential risks to physical and mental health. The main physical health hazards are due to exposure to wildfires and the smoke associated or often compounding extreme heat events experienced in tandem. Impacts on mental health and well-being can also occur or be exacerbated as a result of wildfire events. For example, increased exposure to wildfire smoke and evacuations will put increasing strain on those who live, work and play in the impacted areas. Health hazards and risks can be reduced with comprehensive mitigation and preparedness activities that strengthen both community and individual resilience, raise awareness of protective measures and address inequities with respect to the social determinants of health.

2.1.1) Fire

Wildland fires or wildfires can include unplanned fires (both natural and human-caused) and intentional burning and prescribed fires (as a part of fire management). How wildfires develop and spread depends on the complex interaction between ignition source(s), climate/weather, potential fuel(s), and geographic topography.Footnote 4 At the wildland-urban interface, wildfires can lead to structural fires in the built environment.

Wildfires contribute to the health and diversity of ecosystems and are an important part of the lifecycle of the natural environment. However, if they become too large to control it can create major health hazards and lead to disasters and death. In addition to health impacts wildfires can threaten industry, damage infrastructure and housing, and cause secondary impacts such as soil erosion, increased risk of landslides and flooding after fires.Footnote 5

For more information, refer to: The First Public Report of the National Risk Profile and to Public health risk profile: Wildfires in Canada, 2023.

2.1.2) Smoke

Populations geographically close to wildfires have the highest exposure to wildfire smoke. Additionally, wildfire smoke can travel large distances and can affect the air quality for extended periods of time, meaning populations across Canada face potential exposure.

Wildfire smoke is a complex mixture of gases, particles and water vapour that contains pollutants such as: fine particulate matter (PM2.5), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), volatile organic compounds, and other gases including carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and ozone. Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) is the most commonly measured and studied pollutant in wildfire smoke and is considered the main public health threat from exposure to wildfire smoke. Fine particulate matter is a general term for all small particles found in air measuring equal to or less than 2.5μm in aerodynamic diameter. Since it is so small, this fine particulate matter can be inhaled deep into the lungs, and a small fraction of the particles can enter the bloodstream.Footnote 6 Health Canada recommends that levels of PM2.5 should be kept as low as possible, as there is no apparent threshold that is fully protective against the health effects of PM2.5.Footnote 7 Footnote 8 As smoke levels and duration of exposure to smoke increases, health risks increase.

Carbon monoxide (CO) exposure from wildfire smoke does not pose a significant health hazard to the public, as it does not travel far from the original source. However, if exposed directly (e.g., wildland firefighters) or if the source of the smoke is nearby, CO can be a health hazard indoors. Other pollutants present in wildfire smoke including nitrogen oxides (NOx), polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and volatile organic compounds (VOCs) contribute to the cumulative hazardous potential of exposure. The health effects associated with these pollutants are well understood, however more studies are needed on the exposure to wildfire smoke in order to better understand public health impacts of these other pollutants associated with wildfire smoke exposure. The chemical composition of wildfire smoke is highly variable and determined by many factors including the type and composition of the vegetation burning (e.g., wet or green vegetation versus dead or dry vegetation; forests versus grasslands; hardwood versus softwood; etc.), the physical and chemical processes of the combustion (e.g., flaming versus smoldering), and weather conditions (e.g., temperature, humidity).Footnote 9

For more information, refer to: Guidance for Cleaner Air Spaces during Wildfire Smoke Events and Public health risk profile: Wildfires in Canada, 2023.

2.1.3) Health Effects

Wildfires can impact physical health, as well as mental health and well-being. Close proximity to wildfires can pose immediate risk to individuals from direct contact with fire, as well as smoke-related health effects. Most acute symptoms from wildfire smoke are transient and self-resolving. Milder and more common symptoms of smoke exposure include headaches, a mild cough, a runny nose, production of phlegm, and eye, nose and throat irritation. These symptoms can typically be managed without medical intervention. More serious symptoms that should prompt medical assessment include dizziness, chest pains, severe cough, shortness of breath, wheezing (including asthma attacks), and heart palpitations.

Short-term exposure to wildfire smoke is associated with several health effects including, exacerbations of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and premature death. There is some evidence for an association with cardiovascular health effects (e.g., hospitalizations or emergency room visits for cardiovascular issues) and impacts on birth outcomes (e.g., low birth weight).Footnote 10 Footnote 11 Mental health impacts (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety) associated with wildfires and wildfire smoke have been identified.Footnote 11

There is limited evidence on the long-term health effects from seasonal wildfire smoke, given the episodic nature of wildfires and difficulties in differentiating wildfire-PM2.5 from PM2.5 from all sources. In comparison, there is extensive evidence that, even at current levels of exposure in ambient air, Canadians are at risk of adverse health effects from PM2.5 exposure from all sources, which may include premature mortality, cardiovascular and respiratory outcomes that can require additional medical visits and even result in more severe outcomes including lung cancer. Some people, such as those with pre-existing health conditions (e.g., cardiovascular and respiratory diseases), older adults and children, are at greater risk.Footnote 8 For 2013-2018, Health Canada estimated that 50-240 premature deaths were attributable to short-term exposure to wildfire-PM2.5 annually and 570-2500 premature deaths were attributable to long-term exposure annually, as well as many non-fatal cardiorespiratory health outcomes.Footnote 12

Key considerations when determining the potential population health impacts from wildfire smoke exposure include:

- Exposure characteristics: concentration of PM2.5, duration of exposure and breathing rate

- Population susceptibility: number of people at higher risk, including groups affected by systemic inequities

- Availability of interventions to reduce impacts such as population access to cleaner air spaces

- Concurrent exposures such as heat

With respect to mental health, people impacted by a wildfire event may experience new-onset or exacerbation of existing mental health conditions including psychosis, post-traumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder, and anxiety including generalized anxiety disorder, as well as new or exacerbation of mental health stressors such as grief, trauma, worry, increase in substance use, aggression and violence.Footnote 13 For Indigenous populations evacuations and separation from community or family can lead to re-traumatization as a result of the experiences of historical and intergeneration trauma associated with relocation (i.e. residential schools, sanitoriums).Footnote 14 Pre-existing mental health conditions may lead to worsened mental health symptoms after experiencing a wildfire event. Being in close proximity to the wildfire (e.g., witnessing homes being burnt) and being relocated has also been shown to lead to increased adverse mental health impacts.Footnote 15

Wildfire evacuations have been associated with mental health outcomes, disrupted access to health care, and social well being impact (for more information, see evacuation section of this toolkit). After a wildfire, residents who return home may face financial, health and social stresses of loss of personal property, rebuilding homes and community, in addition to a devastated landscape that serves as a daily reminder of their loss. This can lead to solastalgia, a form of mental or existential distress caused by environmental change.Footnote 16 Exposure to wildfire smoke may also have mental health impacts but the evidence is inconsistent and limited.Footnote 17

- For more information, refer to: Wildfire smoke, air quality and your health and Public health risk profile: Wildfires in Canada, 2023

Additional Resources:

- Human Health Effects of Wildfire Smoke (Health Canada Review)

- Wildfire smoke and your health

- Health impact analysis of PM 2.5 from wildfire smoke in Canada (2013–2015, 2017–2018)

- Particulate matter 2.5 and 10

- Health Effects of Wildfire Smoke

- Rapid Review: What is the effectiveness of public health interventions on reducing direct and indirect health impacts of wildfires?

2.1.4) Smoke and Heat

Extreme heat events may happen at the same time as wildfire smoke, and both can impact health. Extreme heat events can cause significant morbidity and mortality. For example, at least 619 people in BC died during an extreme heat event that occurred June 25-July 1, 2021.Footnote 18 Footnote 19 In most cases, extreme heat is the more immediate risk to health relative to exposure to wildfire smoke and cooling should be prioritized over cleaner air if needed, especially for those most at risk. This includes people over 70 years of age and those with chronic health conditions including schizophrenia, substance use disorder, epilepsy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, asthma, mood and anxiety disorders and diabetes.Footnote 19

For more information, including advice for the public, refer to: Wildfire smoke with extreme heat factsheet and Extreme heat events: Overview

Additional resources:

- Medical health officers' letter about heat and smoke

- Wildfire smoke during extreme heat events

- Continuing Education Course: Wildfire Smoke and Your Patients' Health

- Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate: Advancing our Knowledge for Action

- Extreme heat events: Health risks and who is at risk of extreme heat events

- Communicating the Health Risks of Extreme Heat Events

2.1.5) High risk populations and equity considerations

Everyone's health is at risk from wildfires including the pollutants in wildfire smoke, but some people are at higher risk because they are exposed more frequently to high levels of smoke or they are more likely to experience symptoms or negative health outcomes. People may also be at higher risk because they can not access public messaging or control their indoor air. Groups at higher risk include:

- older adults

- Indigenous Peoples

- people who smoke

- infants and young children

- people living in rural and remote areas

- people who are pregnant

- people involved in strenuous outdoor exercise

- people living in situations of lower socio-economic status such as:

- those with lower income

- those with lower education

- those experiencing housing insecurity

- those experiencing uncertain employment

- people who work outdoors, including wildland firefighters

- people with pre-existing health conditions, such as:

- cancer

- diabetes

- lung or heart conditions

- persons with disabilities

- newcomers to Canada and transient populations

For more information, refer to: Wildfire smoke, air quality and your health.

Populations living in communities closer to high fire-risk areas also experience higher rates of adverse physical and mental health impacts. Indigenous communities, and rural and remote areas are most often evacuated due to wildfires. Some communities have experienced multiple evacuations either in the same wildfire season, year after year or for prolonged periods of time, which may lead to increasing health impacts.

Even in the absence of evacuation, wildfires can restrict access to communities, especially those that are more remote with limited entry/exit points, due to impacts on infrastructure (e.g., highways/roads) and services; this can result in a lack of health and related services including medical supplies, personnel, and food.

Given that the impacts of wildfires can be disproportionately experienced for populations already facing health inequities, it is important that a health equity lens and cultural safety principles be embedded in the public health actions and interventions listed in this document.

For more information, refer to: Public health risk profile: Wildfires in Canada, 2023 and Rapid Review: An intersectional analysis of the disproportionate health impacts of wildfires on diverse populations and communities.

2.2) Partnerships

Wildfire prevention, preparedness, response and recovery is complex, involving intersectoral and interjurisdictional collaboration, community engagement, and the use of many sources of information in decision making. A key strength in public health efforts on any health issue is the value of convening and collaborating across diverse sectors and partners. Public health authorities have long standing relationships and trust with community groups, diverse leaders and response partners through a variety of public health programs and functions that are foundational to supporting community resilience in all aspects of emergency management.

Since 2007, federal, provincial and territorial (F/P/T) collaboration in emergency management has been guided by the Emergency Management Framework for Canada.Footnote 20 In Canada, emergencies are managed first at the local level. This may involve municipalities, fire departments, police, paramedics, hospitals, local public health, and other members of the emergency response team. If assistance is needed at the local level, a request can be made to the applicable province or territory. If the emergency exceeds the province or territory's capacities, the provincial or territorial government can request assistance from the federal government through a Request for Assistance (RFA). Federal support may also be required when the emergency cuts across multiple or all jurisdictions (requires federal coordination), or when the emergency is in a jurisdiction of federal responsibility (e.g., national park land, military bases, some First Nations or Inuit communities).

Once the federal government becomes involved, the federal response is coordinated using the Federal Emergency Response Plan (FERP). In most cases, federal government institutions manage emergencies with event-specific or departmental plans in addition to the processes outlined in the FERP.Footnote 5 The federal government has responsibilities for federal emergency response coordination; disaster financial assistance to provinces and territories; national situational awareness for wildfire events if requested by wildland fire management agencies; and for wildfires on national park land and military bases. The Canadian Armed Forces may also be requested to assist in disaster response (e.g., Operation LENTUS).Footnote 21

At the international level, Canada joined 187 countries at the United Nations (UN) General Assembly in 2015 in adopting the UN Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (2015-2030).Footnote 22 This framework is a non-binding international agreement that establishes international priorities for disaster risk reduction. As a signatory to the Sendai Framework, the Government of Canada has committed to improving resilience strategies, preparedness efforts, early warning systems and cooperation to reduce disaster risks.Footnote 5

In June 2023, Canada released its first National Adaptation Strategy (NAS) which establishes a shared vision for climate resilience in Canada, key priorities for collaboration, and a framework for measuring progress at the national level. The work of the disaster resilience pillar builds on existing work underway for the Emergency Management Strategy and aims to advance priorities on addressing floods, heat events, wildfires, and recovery.

3) Public Health Action and Interventions

Public health authorities at various levels of government may be involved in a variety of actions and interventions across the emergency management continuum with respect to wildfires. Canada's Chief Public Health Officer (CPHO) 2023 annual report, Creating the Conditions for Resilient Communities: A Public Health Approach to Emergencies, explores how public health can work with communities and partners across sectors to build healthier, more resilient communities that are better equipped to prevent, withstand, and recover from emergencies, including wildfires. This includes a list of tangible actions that can be taken to apply a health promotion lens across the emergency management continuum.

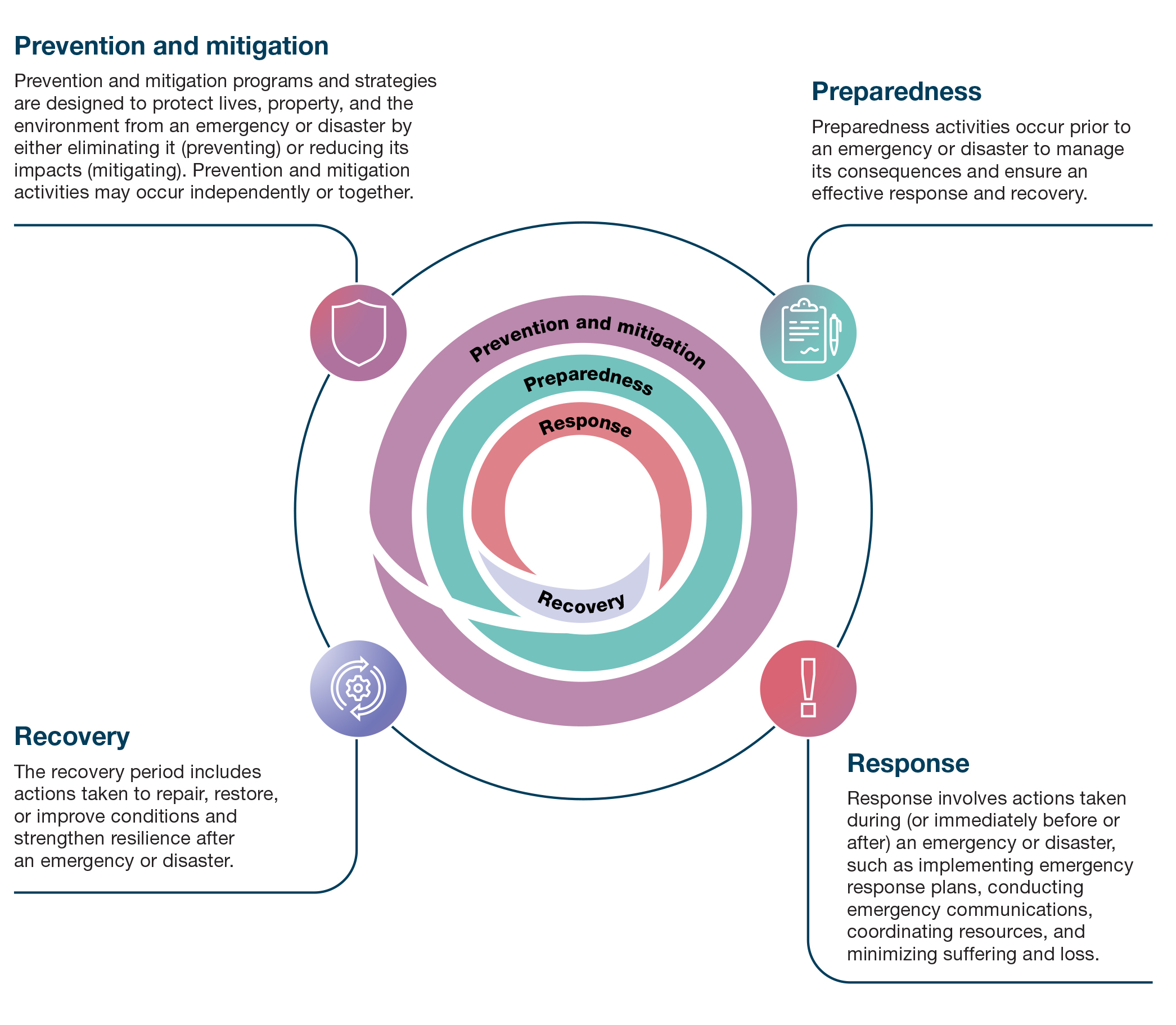

There are potential actions and interventions at each of the 4 phases of the emergency management continuum (Figure 1): mitigation of risk, preparedness, response and recovery. Examples of potential interventions at each phase are offered in subsequent sections.

Figure 1. The Emergency Management Continuum

The 4 components of the emergency management continuum are illustrated in a diagram of concentric circles, with prevention and mitigation in the outside circle, then preparedness, and finally an inner circle that encompasses response and recovery. From the outside circle working in, the components are as follows:

Prevention and mitigation: Prevention and mitigation programs and strategies are designed to protect lives, property, and the environment from an emergency or disaster by either eliminating it (preventing) or reducing its impacts (mitigating). Prevention and mitigation activities may occur independently or together.

Preparedness: Preparedness activities occur prior to an emergency or disaster to manage its consequences and ensure an effective response and recovery.

Response: Response involves actions taken during (or immediately before or after) an emergency or disaster, such as implementing emergency response plans, conducting emergency communications, coordinating resources, and minimizing suffering and loss.

Recovery: The recovery period includes actions taken to repair, restore, or improve conditions and strengthen resilience after an emergency or disaster. The recovery phase blends back into the continuum, demonstrating its influence on prevention and mitigation and preparedness activities.

The wildfire-specific resources in the list below provide content that encompasses all 4 phases of the emergency management continuum. Some specific links from these comprehensive resources are also provided under the respective phase in this document. In addition, available provincial and territorial guidance documents are linked at the end of this document.

Wildfires – this Government of Canada wildfires landing page has resources on the current situation, emergency response, support, recovery, and information for the public.

Wildfire smoke, air quality and your health

Wildfire Smoke and Health | National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health (NCCEH – CCSNE) – this website has multiple resources regarding Wildfire Smoke and Health.

Public health responses to wildfire smoke events | National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health – this resource is meant to better understand the perceptions, challenges and needs of public health practitioners in Canada when responding to wildfire smoke events.

Wildfires (CDC) – this US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention page on wildfires has information on preparing for wildfires, staying safe during a wildfire, and staying safe after a wildfire.

3.1) Prevention and risk mitigation

The two main components of a public health risk are the likelihood the hazard will occur and the potential impact of the hazard on an affected individual, group, population, system or society. From a public health perspective, mitigation of wildfire risk requires an examination of how both components can be reduced to minimize the negative physical and mental health impacts in a population. This includes identification of specific high-risk groups, settings and circumstances, as well as actions that can reduce exposure and vulnerability and enhance capacities and capabilities of whole-of-society emergency management.

3.1.1) Potential public health actions for risk mitigation

Completing a risk assessment, including a climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation (V&A) assessment to better understand potential risk and exposure ahead of the wildfire season.

Public communication and awareness raising initiatives regarding:

- the role of climate change in the occurrence of health hazards like wildfires

- human behaviours that increase the likelihood of a wildfire

- the ways wildfires impact peoples' health

- steps that can be taken in advance to prepare for a wildfire

Public health interventions and health promotion activities to reduce the prevalence of chronic diseases that can put people at higher risk to the adverse effects from wildfires.

Initiatives to reduce inequities with respect to the social determinants of health and bolster individual and community resilience.

Promoting and engaging with communities and partners on wildfire mitigation measures.

Supporting climate change mitigation and adaptation measures.

3.1.2) Tools and resources

The following reports provide context and content that may support the risk mitigation actions identified above.

Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate — Advancing our Knowledge for Action – this Health Canada report from 2022 includes chapters on: Air Quality, Climate Change and Health Equity, and Adaptation and Health System Resilience. A fact sheet on Climate Change, Wildfires and Canadian's Health that is based on the scientific assessment in the report is also available.

Mobilizing Public Health Action on Climate Change in Canada – this 2022 Chief Public Health Officer of Canada report examines the impacts of climate change on the physical and mental health of people in Canada, and the role that public health systems can play including areas of action to prevent and reduce health impacts across the country.

Canadian Wildland Fire Strategy. A 10-year review and renewed call to action – this report of the Canadian Council of Forest Ministers Wildland Fire Management Working Group from 2016 speaks to the need to enhance prevention and mitigation capability through increasing community responsibility and engagement and improving planning through collaboration and consultation with communities, First Nations and stakeholders. This progress report is not health focused but may serve as a reminder of previous commitments and steps that may benefit from public health engagement.

Canadian Wildland Fire Prevention and Mitigation Strategy – Taking Action Together – this strategy, released in 2024, was developed by the Canadian Council of Forest Ministers (CCFM) with an aim to provide a cohesive vision for wildland fire prevention and mitigation efforts.

National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health – this website has multiple resources regarding wildfire smoke and health. The Mitigating Wildfire and Smoke Risks section includes the following resources:

- Wildfire management in Canada: Review, challenges, and opportunities

This peer-reviewed article takes a broad view of wildfire management in Canada, providing important perspectives regarding the need to protect public health and safety while recognizing that current strategies are insufficient. - FireSmartTM Canada

This program, now administered by the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre (CIFFC) is an essential resource for communities and citizens wishing to make their communities and properties "fire smart". Resources include manuals, articles, online courses, in-person workshops, and case studies of FireSmartTM Neighbourhoods across Canada. Many resources are available in both official languages.- FireSmartTM BC homeowner's manual

This excellent illustrated guidebook instructs individual homeowners on how to dramatically reduce the risk that a wildfire will spread within the property. - FireSmartTM guidebook for community protection

This streamlined FireSmartTM toolkit provides essential background information, templates, and tools to help communities develop a wildfire response plan based on local wildfire risk. Communication strategies used in the guide are discussed in this peer-reviewed article.

- FireSmartTM BC homeowner's manual

First Nations Fire Protection Strategy, 2023 to 2028 – this strategy, co-developed by the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) and Indigenous Services Canada (ISC) promotes fire protection on reserve.

Lung Health Foundation – this foundation's website provides content for high-risk populations that links to Government of Canada content on wildfires. However, it also provides content on lung diseases (e.g., childhood asthma, COPD) and how to protect your lungs for the general public.

National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health – this website includes multiple resources that address various aspects of the determinants of health and inequities in Canada, including how to integrate equity values and principles in public health emergency preparedness and management.

National Indigenous Fire Safety Council – this website contains the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) Community Preparedness Digital Tool, National Incident Reporting System (NIRS), as well as programs in seven program areas, two of which focus on fire department management and community governance. The latter supports the development of policies and bylaws, communication plans and fire emergency plans.

3.2) Preparedness

Preparedness for a wildfire event includes identifying and addressing response capabilitiesFootnote 23, specifically outstanding needs and gaps that public health authorities might be able to fill. It may involve working with health and emergency management partners, communities and individuals to build capacity and resilience. For some jurisdictions, wildfires are seasonal events and preparedness involves more "reminders", "re-assessment" and "reinstatement" type activities, whereas for other jurisdictions preparedness activities may include the development of new plans, training and exercises, arrangements/acquisitions, emergency information and public education products. Public health authorities can also partner with communities to allow for more comprehensive understanding of community needs and assets which helps ensure planning accounts for local context and incorporation of equitable approaches.Footnote 24

3.2.1) Potential public health actions for wildfire preparedness

Coordinate with partners and identify roles and responsibilities for public health authorities at all levels of government in the event of a wildfire emergency.

Create emergency response plans for which interventions would be used/recommended under specific circumstances (i.e., with triggers for action).

Identify and ensure timely access to surveillance data streams and foster agreement on data thresholds/ranges that will be needed to inform decision making during response and recovery periods.

Consider not just air pollution but also water and soil contamination, contaminated food sources (animal and animal products), and impact on wildlife that are potentially part of food security.

Identify potential cleaner air space locations, considering cultural needs, safety issues and protocols for use.

Recommend engineering evaluations of HVAC systems for institutions and public locations as needed (e.g., critical infrastructure).

Identify/ensure public health awareness of regions/communities at risk for wildfire smoke events, and identify high risk sub-groups in these areas.

Contribute from a health perspective to public communication and awareness raising initiatives regarding individual and institutional preparedness actions:

- Make personal/institutional emergency response plans for evacuation, sheltering in place, in-home cleaner air space and access to necessary medication and health services (when sheltering in place and in the event of an evacuation).

- How to manage heat and smoke events at the same time.

- Recognizing if you are at high risk for wildfire related physical and mental health hazards and what you can do about it in advance.

- Optimize personal and institutional HVAC systems to maintain clean indoor air.

- Acquisition/access to KN95/N95 respirators.

- Know how to get reliable and timely information about wildfires and air quality conditions.

- Know how to create cleaner air space at home.

- Identify nearest public spaces that can serve as cleaner air shelter.

Identify and plan for mental health supports – including but not limited to:

- Stress related violence

- Companion animal care

- Economic hardship

- Prolonged absence from home, communities, daily routines

- Loss of life, property, culturally significant locations and infrastructure

Consider resource availability, procurement and stockpiling needs for:

- HVAC filters

- Air purifiers

- Air quality monitoring devices

- KN95/N95 respirators

3.2.2) Tools and resources

The following reports provide context and content that may support the preparedness actions identified above.

Preparing for wildfire smoke events– a public educational fact sheet.

Guidance for Cleaner Air Spaces during Wildfire Smoke Events – a guidance product that includes preparedness content pertaining to this intervention.

National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health – this website has multiple resources regarding Wildfire Smoke and Health. The Preparedness and Response Planning section includes the following resources:

- Prepare for the worst: Learning to live with wildfire smoke

This webinar provides an overview of the worsening fire risks in western Canada and demonstrates the almost immediate public health impacts of smoke exposure to the community. The presentation also covers some of the tools and strategies that can be used to reduce health impacts and achieve the necessary state of preparedness for a smokier future. - Planning framework for protecting commercial building occupants from smoke during wildfire events

This guidance document provides detailed information on heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) and other building measures to protect occupants against smoke exposure, while also accounting for potential SARS-CoV-2 transmission. The document outlines how to develop, implement and evaluate a smoke readiness plan, with numerous additional linked resources. - BC Health and Smoke Exposure (HASE) coordination committee guideline

The purpose of this advisory document is to describe the coordination of regional, provincial and federal governments to minimize the public health impacts of wildfire smoke. It describes the roles and responsibilities, and the process of activation, coordination and response to wildfire smoke, as well as assessing outcomes and making recommendations to protect public health interventions. Although specific to BC, this may be useful to policy makers in other jurisdictions. - Wildfire smoke: a guide for public health officials

This guide is designed to help public health officials prepare for smoke events, take measures to protect the public, and communicate with the public about wildfire smoke and health. - Forest fires: a clinician primer

This article succinctly reviews populations most at risk during fire events, tools for situational awareness (e.g., smoke forecasting and environmental monitoring), and steps that can be taken to protect patients. - Guidance for BC public health decision makers during wildfire smoke events

This advisory document provides public health decision makers with current evidence and BC-specific guidance for the assessment of, preparation, and possible interventions for a wildfire smoke event. - Public Health Planning for Wildfire Smoke

This report, which is a follow-up to Maguet (2018) cited below, describes a multi-jurisdictional qualitative inquiry into current public health planning for wildfire smoke events. It also addresses the capacity to respond to wildfire smoke events and perceptions of wildfire smoke as a public health priority.

About FireSmartTM | FireSmartTM Canada – this is a website for a national program that helps increase neighborhood resilience to wildfire and minimize its negative impacts in Canada. It includes multiple preparedness educational resources and tools for the public and has links to provincial and territorial liaisons.

National Indigenous Fire Safety Council – this website contains the Wildland Urban Interface (WUI) Community Preparedness Digital Tool, National Incident Reporting System (NIRS), as well as programs in seven program areas with a focus on fire prevention and public education programs for Indigenous communities.

Emergency Preparedness Guide for Community Members – this guide prepared by the Northern Inter-Tribal Health Authority (updated in 2021) includes information, tools and resources for northern communities, with an emphasis on wildfire smoke-related risk management.

Wildfire smoke and animals – this web content from the American Veterinary Medical Association includes signs and symptoms to watch for in your animals, and tips to protect pets and livestock.

Pets and disasters – this website includes information to plan for disasters and tools like a pet evacuation checklist. There are also links to content for horse owners, and large animals and livestock in disasters.

Wildfire Smoke and Your Patients' Health – this course offered by the American Environmental Protection Agency is intended for physicians, registered nurses, asthma educators and others involved in clinical or heath education. It provides content about the health effects associated with wildfire smoke and actions patients can take before and during a wildfire to reduce potential exposure.

Appendix A – Federal government roles – Wildland fires – this is an example of the mapping of federal government roles and responsibilities. A similar document could be developed as part of preparedness activities that ensure awareness and engagement between public health authorities and partners at other levels of government.

3.3) Response

The public health response to wildfires may vary between jurisdictions. Depending on the roles and responsibilities of the various responders and government departments, public health's involvement could range from providing education and advice, supporting equitable and culturally safe approaches, enabling multi-disciplinary collaboration, to making recommendations, to issuing directive actions. However, in all situations it is expected that the focus of the public health response will be on measures, activities and interventions that reduce the negative physical and mental health impacts of wildfire events. The concurrent use, or "layering", of multiple measures will support a comprehensive response to the health risks.

3.3.1) Potential public health actions for wildfire response

Provide advice/recommend/direct communications, regarding:

- How to assess your risk during smoke events, including visual assessment and how to access and interpret air quality monitoring data (e.g., local AQHI)

- Who is most at risk and what they should do differently

- When to reduce time spent outdoors

- When to decrease physical exertion outdoors

- When to cancel outdoor events

- When to go to a cleaner air space (in home or community) and how to set up one in your home

- Effective use of air purifiers and filters

- How to set up a community cleaner air shelter

- When and how to wear an N95 or equivalent respirator

- What to do when both smoke and heat events are occurring concurrently

- How to access critical medical supplies, services and medications during smoke and fire events

Monitor surveillance data and update messaging and public health actions as needed.

Act as part of an interdisciplinary emergency response team.

3.3.2) Tools and resources

This section provides more in-depth reviews of key potential public health interventions and activities. Links to several tools and resources are embedded in each topic section.

Situational Awareness

Situational awareness and risk assessment involve consideration of weather, wildfire and wildfire smoke forecasting, air quality measurements, and health surveillance data if available. When wildfire, wildfire smoke, and heat events co-occur, it is important to balance the public messaging and interventions to protect from immediate life-threatening effects of heat and wildfire, and secondarily protect against wildfire smoke.

The Enhanced Vulnerability and Capacity Assessment is a participatory process developed by the International Federation of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies that communities can use to assess local risks, where risks come from, who is most exposed, and what actions could be undertaken to reduce risk.

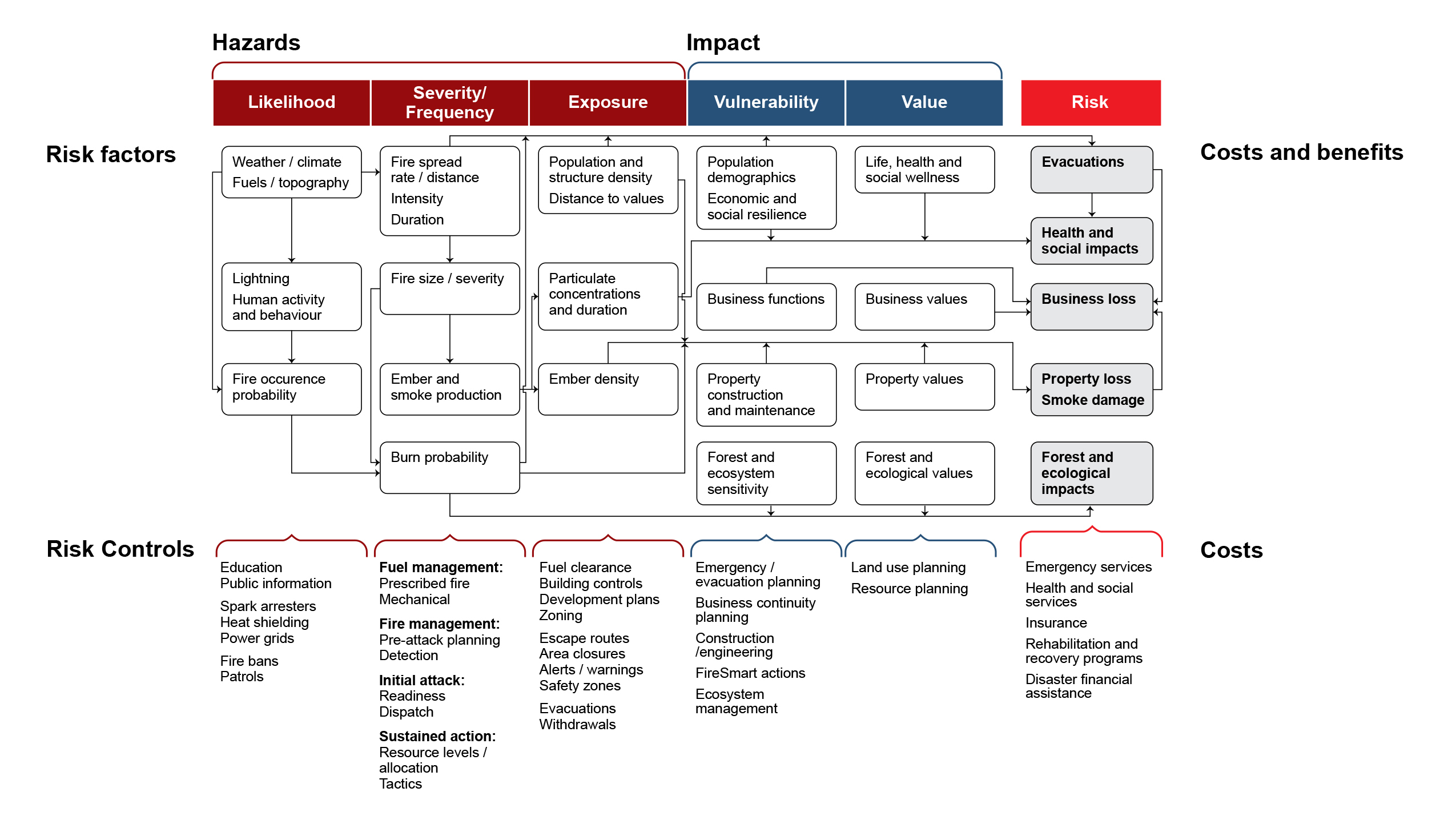

The First Public Report of the National Risk Profile outlines the risks associated with wildfires as summarized in the following figure.

Figure 2: Wildland Fire Risk Logic Model

| Risk factors | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard | Impact | Risk (costs and benefits) | |||

| Likelihood | Severity / Frequency | Exposure | Vulnerability | Value | |

Affects fire spread rate, intensity and duration, lightning and human activity |

Affects evacuations plus fire size and severity |

Affects evacuations and property loss / smoke damage |

Affects evacuations and health and social impacts |

Affects health and social impacts |

Affects health and social impacts, business loss |

|

|||||

Affects fire occurrence probability |

Affects ember and smoke production, burn probability |

Affects health and social impacts, property loss / smoke damage |

Affects business loss |

Affects business loss |

|

Affects burn probability |

Affects ember density |

Affects property loss / smoke damage |

Affects property loss / smoke damage |

Affects property loss / smoke damage |

Affects business loss |

Affects evacuations, property loss / smoke damage, forest & ecological impacts |

Affects property loss / smoke damage |

Affects forest and ecological impacts |

Affects forest and ecological impacts |

|

|

| Risk controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Likelihood | Severity / Frequency | Exposure | Vulnerability | Value | Risk (costs) |

|

Fuel management:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fire management:

|

|

|

|

|

|

Initial attack:

|

|

|

|

|

Sustained action:

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

It can be difficult to predict wildfires and there is a degree of uncertainty to hazard mapping tools. Consultation with experts in wildfires, provincial and territorial emergency management and related threat analysis may be needed.

The Canadian Wildland Fire Information System provides detailed information regarding current and projected wildfires. This includes forecasted weather information provided by the Canadian Meteorological Centre.Footnote 25

The following website: Wildfire risk and Indigenous communities shows the locations of Indigenous communities and their proximity to recent wildfires. The information in this map comes from The Canadian Wildland Fire Information System at Natural Resources Canada.

Air Quality

Smoke Forecasting

FireWork is an air quality prediction system that indicates how smoke from wildfires is expected to move across North America over the next 72 hours.

Air Quality Assessment

There are several methods to assess air quality. Traditional monitoring networks or sites use highly accurate, precise, and standardized instruments (United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) certified federal equivalent method monitors), which require trained technicians to maintain and operate. These sites are the "gold standard" for monitoring regional-scale trends in air quality across large geographic areas and are used by F/P/T governments for establishing air quality trends, assessing air quality impacts on health and the environment, and informing long term F/P/T air quality management strategies and compliance with Canadian ambient air quality standards. As of July 2023, there are 286 sites in 203 communities across Canada under Environment and Climate Change National Air Pollution Surveillance Program.

To provide wildfire smoke information in rural areas, low-cost sensors that measure fine particulate matter (PM2.5) can provide a measurement of these particles with lower accuracy when compared with traditional monitoring networks. These sensors can supplement traditional monitoring networks during wildfire events to better understand differences in pollutant concentrations within communities due to topography, wind direction or proximity to a source and can be particularly useful in rural or remote areas. In collaboration with University of Northern British Columbia, the AQmap is available with real-time data from low-cost sensors and stationary monitors as well as other wildfire smoke products such as map overlays of smoke plumes, active fires, and fire weather index.

Air Quality Health Index (AQHI)

The Air Quality Health Index (AQHI) reaches 81% of the population with 134 locations reporting observations and forecasts across Canada. The AQHI can be found on the Environment and Climate Change Canada weather website, the WeatherCAN app and local weather forecasts.

The Air Quality Health Index was developed in 2007 by Canadian researchers, as a replacement to the single pollutant Air Quality Index, to better communicate the combined short-term health risks from multiple pollutants present in air pollution in Canadian cities. This scale was developed by calculating excess mortality risk due to three pollutants: ozone (03), particulate matter (PM2.5 /PM10), and nitrogen dioxide (N02).Footnote 26 It measures the air quality in relation to health on a scale from 1 to 10+. The higher the number, the greater the health risk associated with the air quality.

Wildfire smoke differs from typical urban smog in that PM2.5 is generally present in higher concentrations. During wildfire smoke situations, the AQHI may under represent respiratory health risks since PM2.5 is most closely associated with short-term respiratory health effects from wildfire smoke.Footnote 27 In response to this concern, British Columbia developed an amendment to the AQHI, called the AQHI+, which reflected the increased respiratory health risks associated with PM2.5 from wildfire smoke. This amendment was validated in 2020 as being a better predictor of asthma-related health outcomes than the AQHI.Footnote 27 Since that time, the AQHI+ has been implemented across Canada by Environment and Climate Change Canada in conjunction with most provinces and territories. The two indices, AQHI and AQHI+ are calculated simultaneously in real time, with the higher value being reported. This is done in the background and the value reported does not state whether it is a AQHI value or an AQHI+ value. It was estimated that across British Columbia, the AQHI+ would be expected to override the AQHI 0.4% of the time during low-intensity wildfire seasons (based on the 2011 season) and 3.8% of the time during high-intensity seasons (based on 2017 data).

As of May 2024, all provinces and territories in Canada, except Quebec, will be using the AQHI+ formula during wildfire season. Quebec uses InfoSmog to predict smoke risk which is calculated using PM2.5 and ozone. More information is available at: How Info-Smog works

AQHI Health Risk Messaging:

AQHI health messages are customized to each health risk category (low, moderate, high and very high) for both the general population and the at-risk population. These messages help people decide whether to modify their outdoor activities or take other measures to protect their health and the health of others in their care.

The evidence to date does not identify any safe exposure-response thresholds to wildfire smoke. The AQHI was found to be associated with a 1% increase in all-cause mortality per unit increase. The AQHI+, in comparison, was found to have a 0.5% increase in all-cause mortality per unit increase. During wildfire smoke situations, the AQHI remains the best indicator of short-term mortality and circulatory risks. However, the AQHI+ best reflects the respiratory risks during these situations.

Figure 3. Air Quality Health Index Risk Scale

The AQHI is measured on a scale ranging from 1 to 10+. The AQHI index values are grouped into health risk categories. These categories help you to easily and quickly identify your level of risk.

- 1 to 3 Low health risk

- 4 to 6 Moderate health risk

- 7 to 10 High health risk

- 10 + Very high health risk

See the section on public messaging for more details on using the AQHI in public communications.

Additional resources:

- BCCDC Air Quality Health Index

- The original research related to the AQHI A New Multipollutant, No-Threshold Air Quality Health Index Based on Short-Term Associations Observed in Daily Time-Series Analyses

- Air Quality Index (AQI) Calculation Method

Subsequent articles specific to the AQHI:

- Guide to Air Quality Health Index forecasts

- Wildfire smoke, air quality and your health

- Alberta Air Quality Notification Protocol: What you need to know

Air Quality Alerts

Special Air Quality Statements (SAQS) or Air Quality Advisories (AQA) may also be issued for impacted communities. SAQS are often sent when the AQHI is expected to be 7 or more (high risk). AQA will be issued when the AQHI is at 10 or more (very high risk) for 3 or more hours due to wildfire smoke. SAQS and AQA contain information about the source, expected duration of wildfire smoke events and advice on how to protect health during smoke events. In areas without monitors other methods including satellite, air quality forecast modeling (FireWork), upstream observations and low-cost sensors can be used to determine if an SAQS or AQA is needed. These statements can be found on the Environment and Climate Change Canada website, WeatherCAN app, or often through local weather forecasts.

Indoor air

Protecting indoor air at home from wildfire smoke

When air quality is poor, people should be advised to limit their time outdoors. People can take steps to protect their indoor air from wildfire smoke at home to reduce sources of indoor air pollution and prevent infiltration of outdoor air.

This includes keeping windows and doors closed as much as possible, using a clean, good quality air filter in home ventilation systems based on the manufacturer's recommendations, using a certified portable air cleaner that can filter fine particles and limiting the use of exhaust fans, such as bathroom fans.

Some populations at greater risk of smoke exposure may also be in the lowest income brackets, live in sub-standard housing and may not have access to a ventilation system or portable air cleaner. They may plan to use a Do-It-Yourself (DIY) air cleaner. There is some evidence that DIY air cleaners can be an effective option in short-term emergency situations. It's important that people understand the limitations and safety risks associated with DIY air cleaners.

When an extreme heat event occurs with wildfire smoke, people should protect themselves from the heat first and foremost and prioritize keeping cool. It can be challenging for people to know if they should open windows for cooling or close windows due to the smoke.

People should stay cool indoors by using an air conditioner. If they do not have air conditioning and the outdoor temperature is cooler than the indoor temperature, opening windows can help cool the home.

When windows can be kept closed, keep indoor air as clean as possible by using a clean, good quality air filter in the ventilation system and/or a portable air cleaner to filter particles from wildfire smoke out of the air.

Cleaner air spaces

If people can't maintain cleaner air indoors or don't have air conditioning and it's too warm to stay inside with the windows closed at home, they may need to seek out community-based Cleaner Air Spaces that are created and/or managed by local jurisdictions. Cleaner Air Spaces are important for protecting large numbers of people in your community most at risk of the health effects from wildfire smoke. Creating Cleaner Air Spaces is an effective intervention to reduce population level exposure to wildfire smoke.

Provision of a community-based Cleaner Air Space by a jurisdiction requires planning to ensure that the building is suitable for housing large numbers of people and protecting their health. Buildings such as libraries, community centres, malls and schools may appear to be suitable as Cleaner Air Spaces due to their ability to house large numbers of people, but steps need to be taken to maintain or improve the indoor air quality in these buildings in the event of wildfire smoke. The choice of one building over another will depend on what is deemed appropriate and available for use as a Cleaner Air Space in each individual community.

For more detailed advice and a checklist for how to select or retrofit a building to be used as a Cleaner Air Space, please consult Health Canada's Guidance for Cleaner Air Spaces during Wildfire Smoke Events.

Additional resources:

- Evidence review: Home and community clean air shelters to protect public health during wildfire smoke events (PDF, 389 KB)

- Can Public Spaces Effectively Be Used as Cleaner Indoor Air Shelters during Extreme Smoke Events?

- Portable air cleaners should be at the forefront of the public health response to landscape fire smoke

- Do-it-yourself (DIY) air cleaners: Evidence on effectiveness and considerations for safe operation

Fact sheets for the public:

- Health Canada infographic - Using a portable air cleaner to improve indoor air

- BCCDC wildfire fact sheet: Do-it-yourself air cleaners (PDF, 1,049 KB)

- BCCDC wildfire fact sheet: Portable air cleaners for wildfire smoke (PDF, 3.6 MB)

- FNHA wildfire smoke and clean air shelters (PDF, 122 KB)

Respirator Mask Use

Respirator masks are one layer of protection which can be used to protect against exposure to PM2.5 from wildfire smoke. Respirator masks may be especially beneficial for high-risk populations during wildfire smoke events; however, consideration should be given to an individual's ability to wear a respirator mask safely given their underlying health conditions. The best way to protect health is to reduce exposure to wildfire smoke. Ways to do so include reducing or rescheduling outdoor activities. Individuals can stay indoors and keep the doors and windows closed in their home if the temperature isn't too high. Advice can also be provided for individuals and organizations to use a clean and good quality air filter in ventilation systems and/or using a portable air cleaner.

If individuals must spend time outdoors, a well-fitting and properly worn NIOSH-certified N95 or equivalent respirator (KN95 or KF94) mask can help reduce exposure to fine particles which pose the main health risk from wildfire smoke. It does not protect against the gases in smoke. When wearing a respirator, it is important that individuals listen to their body. If someone needs to remove their respirator, they should try to move to an area with cleaner air before removing it.

Respirators should not be used by children under 2 years of age, someone who has trouble breathing while wearing the mask or someone who needs help to remove it.

During extreme heat events, wearing a mask may affect thermal comfort and contribute to heat stress in some people.

NIOSH-approved Particulate Filtering Facepiece Respirators:

Assessment of international products:

Additional resources:

- Evidence Review: Using masks to protect public health during wildfire smoke events

- Respiratory Protection Information Trusted Source

- Non-occupational Uses of Respiratory Protection – What Public Health Organizations and Users Need to Know

- Non-Fit Tested Respirators for Wildfire Smoke Protection in the Community Setting

- During public health emergencies, provinces and territories can request respirator masks and other emergency supplies from the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile. Information is located at: National Emergency Strategic Stockpile (NESS)

Fact sheets for the public:

- Using a respirator mask during wildfire smoke events

- BCCDC wildfire fact sheet: Respiratory protection for wildfire smoke

- Wildfire Smoke: Frequently Asked Questions | WorkSafeBC

- Face Masks for Wildfire Smoke Poster May 2023

- A Guide to Air-Purifying Respirators, DHHS (NIOSH)

- Elastomeric Respirators, CDC (NIOSH)

Evacuations

Evacuations are an intervention which may be used in response to wildfire. As with all interventions, it is important to consider the full spectrum of risks and benefits of an evacuation for a community as a whole and its diverse members. In collaboration with other professionals (e.g., emergency management, public health), local leaders (municipal elected officials, First Nations Government leadership), community organizations, and others may determine that a community must evacuate due to the imminent risk of a wildfire. Most evacuations occur due to proximity to a wildfire and not due to smoke.Footnote 34 Wildfire smoke conditions may change rapidly, affecting the need and risk-benefit considerations for evacuation. Strong consideration should be given to the use of other protective actions to enable both safety and overall community well-being and stability, such as sheltering in place and establishing cleaner air spaces in the affected community.

There are significant and broad risks to the health and well-being of communities from evacuation, including both mental health and socioeconomic effects.Footnote 29 A Rapid Review prepared by the National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools and The National Collaborating Centre for Environmental Health in October 2023 found that the negative consequences of evacuation experiences (e.g., fear, uncertainty and confusion, anxiety, financial loss) can have enduring impacts on populations stressing the importance of communication, preparedness and planning (moderate confidence of evidence). It also highlighted that relocating evacuees together can provide an opportunity to strengthen cohesion, altruism and support which is important for overall community resilience.Footnote 30

Wildfires and related evacuations have specific and disproportionate effects on Indigenous Peoples and remote communities. Indigenous communities are more likely than other communities to be evacuated often experiencing repeated and prolonged displacement from their homes and communities due to natural disasters. Pre-existing disparities in health status, such as a higher prevalence of respiratory disease in these populations, as well as socioeconomic vulnerabilities in some Indigenous communities and disruption of continuous access to social and cultural supports can lead to increased impacts on Indigenous Peoples.Footnote 5 The legacy and continuation of colonial practices that have led to negative exposure, impacts, and may negatively affect the capacity to respond to and recover from wildland fire emergencies and evacuation for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities. Intergenerational trauma and lack of culturally safe practices has a negative impact on the process of evacuating and relocating to evacuation centres in host cities. This may result in re-traumatization due to the cultural dislocation and trauma associated with geographic displacement, systemic racism, and culturally inappropriate services.Footnote 31 Indigenous evacuees have faced inadequate language, cultural, health and spiritual supports, insufficient or crowded communal and hotel accommodations, and racist treatment while evacuated.Footnote 14 Footnote 32 Evacuation can also result in disruption of traditional and subsistence activities, and traditional healing medicines and foods, which can negatively impact health, mental and spiritual well-being.

Evacuations can significantly disrupt continuity of care and access to healthcare, including both acute and primary care services, as well as long-term care, home care and other social services and supports. They may disrupt access to medications, prescriptions and medical aids creating a risk for people with underlying health conditions.Footnote 33 Footnote 34 They can also disrupt continued access to support for people who use substances and/or mental health services.Footnote 35

The mental health impacts associated with evacuations may include stress, worry, fear, depression (including major depressive disorder), anxiety (including generalized anxiety disorder), post traumatic symptoms (including post-traumatic stress disorder), suicidal ideation (including suicide), and addictions. These can be new onset or exacerbation of an existing condition and can be acute or long lasting. Some populations are particularly at risk for adverse mental health impacts associated with evacuations and they include women, children, youth, young adults, those that do not identify within the gender binary, those with preexisting poor mental health, experiencing lower social economic status, as well as racialized individuals and Indigenous communities. Footnote 15

Evacuations may also have financial and social impacts including additional financial burden on individuals and costs associated with an evacuation (e.g., loss of work, delays in reimbursement or assistance programs), which can lead to family and social separationFootnote 29, and may contribute to increased risk of family violence as a result of the additional stress placed on families and individuals.Footnote 13

If a decision is taken by local leaders to evacuate a community, taking proactive steps to minimize the impacts of evacuation on communities is important.Footnote 36 It is essential that communities who have experienced extensive wildfire events or are at high risk of evacuation plan ahead engaging public health, health care and social services, and local community members with lived and living experience both to support evacuation planning, as well as return and recovery. Supporting evacuated communities by building capacity and readiness in the receiving or host communities is key to building relationships for successful evacuation and recovery. Potential host communities can be identified ahead of wildfire season to ensure they have capacity (e.g., appropriate housing/lodging and bedding for all, human resources and wrap-around services, culturally appropriate and healthy food) and appropriate supports in place.Footnote 37 Authentic relationships between the evacuated and host communities can lead to important knowledge sharing which in turn can result in better planning and preparedness for future events. Host communities can help lessen the impacts of evacuation by providing culturally sensitive and safe health and social services and educating community members on the roles and responsibilities of a host community to reduce stigma and racism. Ensuring access to primary care, pharmacy services, specialized health services and mental health supports to evacuees is important to address medication and health needs and to provide support and continuation of care during a time of turmoil and upheaval.Footnote 18 Footnote 34 It is equally important for the leadership in Indigenous communities to work with Health Emergency Management coordinators, local public health and host communities to ensure their Health Emergency Plans are routinely tested and updated. These plans assist Indigenous communities to prepare for, mitigate and respond to events requiring community evacuation.

Readiness of public health services for evacuees should also be considered in the host community ranging from ensuring inspection of evacuation or eating facilities to prevention and control of communicable disease hazards (e.g., communicable disease outbreaks in the evacuated or host communities), offering harm reduction services and immunization.

Providing immediate financial support and simplified reimbursement processes can lessen the financial loss of evacuation. It is important to plan for recovery, return and continued support for evacuated families, in particular mental health and social supports, as psycho-social impacts from evacuations can emerge or last for years.Footnote 38 Factors such as gender, health and mental health status, place of residence, having livestock or companion animals, and ethnic/cultural identity may impact individuals differently during evacuations and should be considered.Footnote 15

During public health emergencies, provinces and territories can request respirator masks and other emergency supplies from the National Emergency Strategic Stockpile. Information is located at: National Emergency Strategic Stockpile (NESS)

For more information, refer to:

- Evacuations and your mental health

- Risk to Indigenous peoples and remote communities in The First Public Report of the National Risk Profile (section 5.2.2).

- Health and Social Impacts of Long-term Evacuation

Additional resources:

- Public health risk profile: Wildfires in Canada, 2023

- Rapid Review: What is the effectiveness of public health interventions on reducing direct and indirect health impacts of wildfires? (NCCMT)

- Rapid evidence profile #53 (Appendices): Examining the effectiveness of public health interventions to address wildfire smoke, heat and pollutants

- Guidance for BC Public Health Decision Makers During Wildfire Smoke Events

- Health Emergency Management BC (HEMBC)- Inter- and intra-health authority relocation (IIHAR) toolkit

- Smoke exposure from wildland fires: Interim guidelines for protecting community health and wellbeing

- Forest fire smoke and air quality: Public health guidelines – Newfoundland and Labrador

- Yukon wildfire smoke response guidelines 2020

- Wildfire Smoke and Protective Actions in Canadian Indigenous Communities

- Responding to Wildfire Smoke Events

- Health needs during the evacuation of a First Nation – Fact sheet for Health System Partners

- Disaster Response for Mental Health Care Providers – this document outlines tips to mental health care providers on how to support people during a disaster to increase sense of safety, self-efficacy, connectedness, and access to information.

- Post-disaster emergency response: Supporting people who use substances – this web content from the National Collaborating Centre for Environment Health outlines some helpful information for emergency response to support people who use substances.

- Pets and disasters - to plan for disasters and includes tools like a pet evacuation checklist. There are also links to content for horse owners, and large animals and livestock in disasters.

Public Messaging

Effective risk communication with the public is important to achieve public health objectives during wildfire smoke events. Risk communication aims to communicate during potential crisis and emergency situations, inform people about the hazard(s), share directive actions, promote goodwill, and reduce panic.Footnote 39

Some resources for risk communication that may be useful when framing and delivering public messaging during a wildfire response include:

- The Crisis and Emergency Risk Communication (CERC) manual and associated wallet card

- Identifies the 6 principles of risk communication: be first, be right, be credible, express empathy, promote action, and show respect.

- The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)'s Seven Cardinal Rules of Risk Communication (adapted from Covello and Allen, 1988)Footnote 40

Based on a recent rapid evidence profile by McMaster Health Forum, additional considerations for risk communication during a wildfire event include using short health-alert-style messages with plain-language content (including information on guidance, timeframe, geographic location, and specific hazards) and aiming for tailored, translated and more frequent messaging. With respect to communication channels, the evidence profile also identified that television, online (including social media) and smart phone based (e.g., mobile apps) communications are generally preferred sources of information. However, older adults and other populations who may have increased exposure or health risks, may prefer or only have access to radio and television communications.Footnote 41 Also some people may not have access to mobile phones and/or internet, therefore radio and door to door messaging may be the only way to reach certain communities/populations (e.g., northern, remote and isolated communities or individuals).

When communicating with the public during the response phase of a wildfire, it is important to understand local community context and to adapt and update messages accordingly.

Public messaging during a wildfire response may include:

- What wildfire smoke is

- The level of risk and populations most at risk

- Short- and long-term health effects

- Recommendations on how to protect health

- Information on the combined risk of smoke and heat (where applicable)

- Specific messaging for at risk populations

- Mental health considerations

- Sharing directive actions from response agencies

Example of key messages for the public to protect themselves during a wildfire event:

For those affected by fire :

- Be prepared to evacuate. Have a bag with important documents and medications at the ready. If told to evacuate, do so.

- Monitor local radio stations or news channels for up-to-date information on the fire and possible road closures.

- If you do not need to evacuate, follow instructions on how to minimize fire damage, and protect your indoor air.

- Move all combustibles away from the house, including firewood and lawn furniture. Move any propane barbeques into the open, away from structures.

For those affected by smoke :

- Check local air quality conditions using the AQHI, InfoSmog (Quebec), special air quality statements or air quality advisories to determine whether smoke is impacting your area.

- Limit time outdoors. Listen to your body. If you experience symptoms of wildfire smoke exposure, consider reducing or stopping strenuous outdoor activities. If you're among the groups who are more likely to be impacted by wildfire smoke, you should reduce or reschedule strenuous activities outdoors and/or seek medical attention if experiencing symptoms of wildfire smoke exposure.

- If you need to work outdoors, check with your provincial or territorial occupational health and safety organization or your local health authority. They can provide guidance on how to reduce your exposure while working outdoors during wildfire smoke events. Protect your indoor air from wildfire smoke by:

- keeping windows and doors closed as much as possible. When there's an extreme heat event occurring with poor air quality, prioritize keeping cool

- using a clean, good quality air filter in your ventilation system based on the manufacturer's recommendations

- using a certified portable air cleaner that can filter fine particles

- limiting the use of exhaust fans, such as bathroom fans

- If you don't have access to a ventilation system or portable air cleaner, you may plan to use a Do-It-Yourself (DIY) air cleaner. There's some evidence that DIY air cleaners can be an effective option in short-term emergency situations. It's important to understand the limitations and safety risks associated with DIY air cleaners. If you choose to use DIY air cleaners:

- use a clean, newer (2012 or later), certified box fan with a safety fuse

- keep the fan away from walls, furniture and curtains

- change the filters regularly during wildfire smoke events as clogged filters may cause the fan to overheat and lead to fires

- never leave the fan unattended while in use or while you're sleeping

- never leave children unattended when the fan is in use

- don't use an extension cord

- don't use a damaged or malfunctioning fan

- Change the filters of your ventilation system, portable air cleaner and DIY air cleaner regularly during wildfire smoke events. Clogged filters aren't effective at removing smoke.

- If you need more support during a wildfire smoke event, contact your local authorities for information on local cleaner air spaces. Seek out local cleaner air spaces to take a break from the smoke, especially if you can't maintain cleaner air indoors during a wildfire smoke event and/or don't have air conditioning and it's too warm to stay inside with the windows closed.

- If you must spend time outdoors, wearing a well-fitting and properly worn respirator mask (such as a NIOSH-certified N95 or equivalent respirator mask) can help reduce your exposure to the fine particles in smoke. These particles generally pose the greatest health risk from wildfire smoke. However, respirator masks do not reduce exposure to the gases in wildfire smoke. When wearing a respirator mask, it is important to listen to your body. If you need to remove your respirator, try to move to an area with cleaner air before removing it. Respirator masks should not be used by children under 2 years of age, someone who has trouble breathing while wearing the mask or someone who needs help to remove it.

- Taking care of your mental health can help you to cope with challenges experienced during a wildfire smoke event. By being mentally healthy and improving emotional strength you can increase your coping skills and resiliency, including how you handle stressful experiences. It's not unusual to feel worried, stressed out, sad or isolated during a smoke event. Eating well, getting enough sleep, exercising indoors in a place with cleaner air and staying in contact with friends can help. If you're having trouble coping, you may want to consider seeking help from a friend, family member, community leader or health care provider.

It is important to develop tailored messages for people at higher risk during a wildfire response. At risk populations in particular should be advised to listen to their bodies and to reduce or stop activities if they are experiencing symptoms. For more information, visit: Wildfire smoke, air quality and your health.

The recent rapid evidence profile from McMaster Health Forum also pointed to the need for short plain-language content that is tailored to specific populations, notably those who do not speak English and those who are unable to adhere to advice for the general population (e.g., individuals who are homeless or precariously housed). However, additional research is needed to identify the most effective ways to target risk communication for populations at the highest risk of smoke exposure. Public health authorities may want to consult local or regional service providers and advocates to determine the best way to reach specific populations.

Additional resources:

- Which Populations Experience Greater Risks of Adverse Health Effects Resulting from Wildfire Smoke Exposure?

- Effectiveness of public health messaging and communication channels during smoke events: A rapid systematic review

- Public Health Messaging for Wildfire Smoke: Cast a Wide Net