2019 First Annual Report of the Disability Advisory Committee: Enabling access to disability tax measures

This report is dedicated to Wendall Nicholas, for his commitment and leadership as a member of the Disability Advisory Committee.

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Section 1 – Understanding disability tax measures

- Section 2 – Enabling DTC access through improved eligibility criteria

- Section 3 – Enabling DTC access through improved application procedures

- Health provider roles

- Health providers as gatekeepers

- When tax preparers/promoters and health providers disagree on eligibility

- When health providers may not have the information base necessary to completing Form T2201 on behalf of applicants

- When an applicant has more than one severe and prolonged impairment in an activity of daily living

- Expanding the list of health providers qualified to complete Form T2201

- Costs of completing Form T2201

- Clarity of Form T2201

- Layout of Form T2201

- Clarification letters

- Request a review / Appeal a decision

- Quality assurance framework

- Health provider roles

- Section 4 – Enabling access to DTC through improved communications

- Section 5 – Enhancing access to other disability benefits

- Section 6 – Recognizing the additional costs of disability

- Appendix 1 – List of Committee Members

- Appendix 2 – Recommendations

- Appendix 3 – Disability Advisory Committee Terms of Reference

- Appendix 4 – List of Organizations We Heard From

- Appendix 5 – Health Providers Survey

- Appendix 6 – Financial Advisors and Tax Preparers Survey

- Appendix 7 – Description of Federal Measures for Persons With Disabilities

- Appendix 8 – Disability Measures Linked to DTC Eligibility

- Appendix 9 – Form T2201

- Appendix 10 – DTC Data for Mental Functions

- Appendix 11 – RDSP Concerns

- Appendix 12 – Questions for DTC Refundability Conference Call

Introduction

Disability Advisory Committee

The Disability Advisory Committee was originally formed in March 2005 after the Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) on Tax Measures for Persons with Disabilities had completed its mandated work and released its report Disability Tax Fairness in 2004. The Committee subsequently was disbanded in 2006. Because of increased attention to the disability tax credit (DTC) and its administration, the Honourable Diane Lebouthillier, Minister of National Revenue, announced the reinstatement of the Committee in November 2017.

The Minister of National Revenue and the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) are committed to ensuring that all Canadians receive the tax credits and benefits to which they are entitled. The Committee is a forum that enables CRA officials to come together with stakeholders to better incorporate the views of Canadians with disabilities into the Agency’s decision making and procedures.

Committee members are providing their insights on ways to improve access to various tax measures for Canadians with disabilities. Enhancing the accessibility of CRA services to persons with disabilities is an ongoing effort, which has been assisted by the Committee’s work.

Committee membership

The Committee is composed of nine voluntary members including persons with disabilities, health providers and professionals from a variety of fields, such as tax professionals and lawyers. See Appendix 1 for the list of Committee members who contributed to the report. The Committee is co-chaired by Dr. Karen R. Cohen, Chief Executive Officer, Canadian Psychological Association, and by Frank Vermaeten, Assistant Commissioner, Assessment, Benefit, and Service Branch, CRA. A 10th member of the Committee, Ms. Sherri Torjman, former co-chair of the TAC, serves as vice-chair. Ms. Torjman has been retained on contract by the CRA to support the Committee in co-ordinating its activities and fulfilling its reporting obligations.

Mr. Vermaeten, as co-chair of the Committee, functioned as the liaison between the Committee and the CRA. Under Mr. Vermaeten’s leadership, the CRA assisted the Committee in its work, providing secretariat services as well as research and communications support.Footnote 1

The Committee’s work is independent and impartial. During the first year of its mandate, the Committee identified research interests and led initiatives to study these areas in greater detail. The report that follows outlines the findings and recommendations, as developed and articulated by the Committee. See Appendix 2 for a full list of the recommendations.

Committee mandate

The mandate of the Committee is to provide advice to the minister of national revenue and the commissioner of the Agency on:

- the administration and interpretation of the laws and programs related to disability tax measures;

- ways in which the needs and expectations of the disability community can be better taken into consideration;

- increasing the awareness and take-up of measures for persons with disabilities;

- how to better inform persons with disabilities and various stakeholders about tax measures and important administrative changes; and

- current administrative practices and how to enhance the quality of services for persons with disabilities (see Appendix 3).

Committee work

Our committee met four times since its reinstatement. In addition, Committee members participated in one of four working groups set up to explore certain issues in depth. Working groups focused on stakeholder engagement, health provider concerns, tax preparer and financial advisor considerations, and policy/legislative questions. Unfortunately, the working group on Indigenous issues was curtailed by the untimely passing of Committee member Wendall Nicholas. We plan to address these issues in our future work.

The deliberations and recommendations of our committee were shaped by what we heard from individual Canadians, organizations representing persons with disabilities, health providers, tax preparers and policy experts. Early in our mandate, the Committee issued an open invitation to Canadians and organizations representing persons with disabilities to share with us the challenges they faced regarding the DTC and disability tax measures, more generally. We received responses from 53 private individuals and 34 organizations (see Appendix 4).

The Committee also conducted a survey of health providers with respect to DTC eligibility criteria and administrative procedures (see Appendix 5). An online questionnaire was sent to seven national organizations representing the health providers who can certify a DTC application (Form T2201, Disability Tax Credit Certificate) discussed below. We received 1,164 responses to the questionnaire, including several hundred additional comments.

A comparable survey was designed to seek the views of tax preparers and financial advisors (see Appendix 6). We look forward to incorporating their responses in future work. Similarly, a client experience survey will be developed in the coming months to gather information from current and former DTC recipients.

Finally, we reviewed relevant parliamentary reports as well as Disability Tax Fairness, produced in 2004 by the TAC on Tax Measures for Persons with Disabilities. Our committee also heard from a few academics who sent us studies on the DTC. We organized a conference call involving selected experts on the question of DTC refundability. Concurrently to the Committee’s work, several Committee members made a presentation to the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology about the DTC and registered disability savings plans, and the co-chair was asked to present to a local group of health providers about the DTC and the Committee’s work.

Committee proposals

Our committee wants to acknowledge that Canadians are fortunate to have a DTC. This vital measure recognizes the potential impact of severe and prolonged disability upon individuals’ disposable income as well as their capacity to earn that income. At the same time, we heard about the many challenges embedded in the design and delivery of this tax measure, described below.

The DTC eligibility criteria, discussed in Section 2, comprise the first set of challenges. We document the wide-ranging concerns we heard from DTC applicants, current beneficiaries and hundreds of health providers. Our committee proposes both modest clarifications and significant changes to the existing eligibility criteria.

We turn our attention in Section 3 to DTC administrative practices. Regardless of whether the DTC eligibility criteria remain the same or change in response to our recommendations, DTC applications must be processed more fairly and effectively. Our committee makes several proposals for improved administrative practices. We also suggest the development of a quality assurance framework for ongoing monitoring and improvement of DTC eligibility procedures.

We focus in Section 4 on better communications around the DTC and disability tax measures, more generally. Most Canadians, and especially those with disabilities, are unaware of the range of benefits to which they may be entitled. We are particularly concerned about reaching Indigenous Canadians. We are also concerned that some individuals who have an impairment may need assistance to apply for the DTC and to access other tax provisions.

Our committee discussed at length the fact that the DTC has evolved beyond its original purpose. It is now more than just a measure that recognizes additional costs associated with severe and prolonged disability. It also acts as a screen for other crucial disability benefits. This expanded role has given rise to unique challenges that we consider in Section 5.

The final section of our report discusses various issues around disability-related costs. These involve not only the DTC but also the medical expenses tax credit for medical expenses and the disability supports deduction. It is essential to resolve these cost concerns, given the high rate of poverty among persons with severe disabilities.

Taken together, our recommendations seek to ensure that:

- DTC eligibility criteria are clearer, clinically relevant and empirically based;

- DTC administrative procedures are more transparent and fair;

- CRA materials and communications are more accessible and widely available;

- barriers embedded in the DTC gateway function are reduced or removed; and

- more attention is paid to the need for assistance for disability-related costs, bearing in mind the disproportionately high rate of poverty among persons with severe disabilities.

Our primary purpose in this first year of our work was to improve access to the DTC. However, where appropriate, we raised broader issues that we thought the CRA and/or the federal government, more generally, should address.

Finally, but perhaps most important, our work was guided by the principle of fairness. We hope that this principle also helps guide future CRA work.

Section 1 – Understanding disability tax measures

The Committee serves as an important forum to provide the CRA with feedback on the administration of tax measures for Canadians with disabilities (see Appendix 7). These include the:

- disability tax credit (DTC);

- medical expense tax credit;

- refundable medical expense supplement;

- disability supports deduction; and

- Canada caregiver credit.

There is also a set of disability tax measures and programs that require DTC eligibility (see Appendix 8). They include the child disability benefit and the registered disability savings plan (RDSP).

Disability tax credit (DTC)

While the mandate of the Committee includes this range of tax measures, our discussions focused primarily upon the DTC for the first year of our work. This tax measure plays two key roles.

First, the DTC helps recognize the additional costs that persons with severe disabilities may face. Second, it acts as a screen for a range of other disability-related programs and services. We discuss this gateway function later in the report.

The DTC provides tax relief to individuals with severe and prolonged impairments in function that restrict them in the basic activities of daily living or who are blind. It is also available to those who require therapy in order to sustain a vital function.

The credit is based on the assumption that these individuals likely incur a range of disability-related costs that they are not able to claim under the medical expense tax credit. The DTC also assumes that persons with severe and prolonged disabilities likely have their income-earning capacity negatively affected because of the extra time they must devote to their severely disabling condition. The purpose of this tax measure is to help persons with disabilities retain more from their work efforts.

DTC applicants must have a severe and prolonged impairment in physical and/or mental functions that impedes their ability to carry out the activities of daily living. An impairment is considered prolonged if it is expected to last or has lasted at least 12 months.

In order to qualify for the DTC, individuals must submit application Form T2201, Disability Tax Credit Certificate. A designated health provider must certify the type, extent and expected duration of impairment (see Appendix 9).

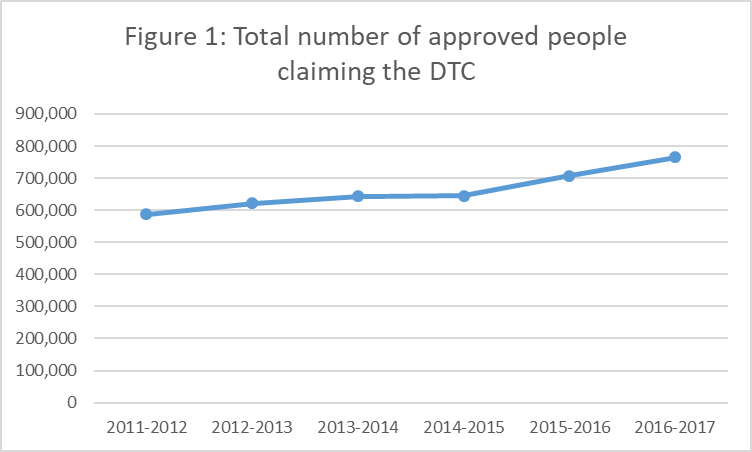

The DTC plays a significant role among disability measures. At last count in the 2016 to 2017 fiscal year, some 770,000 individuals claimed the DTC. The DTC expenditure increased steadily in real terms from 2011 to 2017.

Text version

| Year | Total Number of approved people claiming Disability Tax Credit |

|---|---|

| 2011-2012 | 586,909 |

| 2012-2013 | 622,044 |

| 2013-2014 | 643,940 |

| 2014-2015 | 644,479 |

| 2015-2016 | 706,968 |

| 2016-2017 | 765,072 |

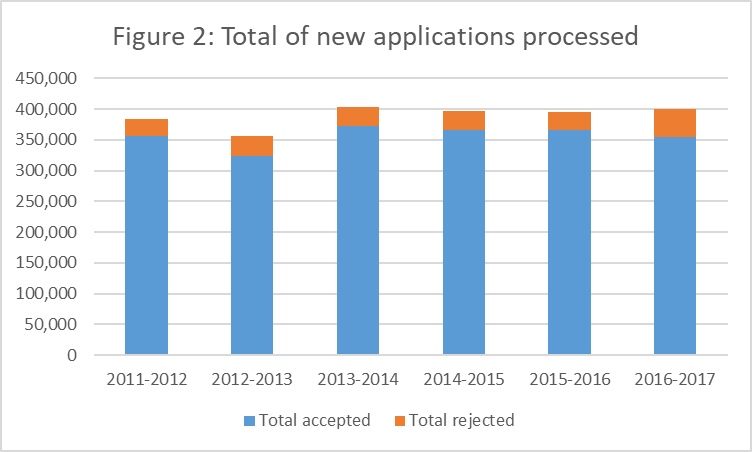

But while the caseload appears high and costs have been rising, significant numbers of applicants have also been refused the DTC. Figure 2 shows the number of applications, approvals and rejections from 2011 to 2017.

Text version

| Year | Total accepted | Total rejected |

|---|---|---|

| 2011-2012 | 355,900 | 27,329 |

| 2012-2013 | 324,368 | 32,023 |

| 2013-2014 | 373,143 | 30,400 |

| 2014-2015 | 365,991 | 30,462 |

| 2015-2016 | 365,274 | 30,235 |

| 2016-2017 | 354,798 | 45,157 |

The data are especially valuable in helping to identify where specific problems may lie. The relatively high rate of rejection of applications in mental functions category is particularly noteworthy. The data are consistent with the concerns raised in submissions to our committee and in the responses to the health provider survey.

It has long been recognized that the DTC eligibility criteria are complex and difficult for both persons with disabilities and health providers to understand. It is these eligibility criteria to which we now turn.

DTC eligibility criteria

There are different ways for which a person can be eligible for the DTC. The person must meet one of the following criteria:

- is blind;

- is markedly restricted in at least one of the basic activities of daily living;

- is significantly restricted in two or more of the basic activities of daily living (can include a vision impairment); or

- needs life-sustaining therapy.

In addition, the person's impairment must meet both of the following:

- is prolonged, which means the impairment has lasted, or is expected to last for a continuous period of at least 12 months; and

- is present all or substantially all the time (at least 90% of the time).

Section 2 – Enabling DTC access through improved eligibility criteria

Introduction

For years, persons with disabilities, members of Parliament, health providers and academics have expressed concern about the policy and administrative aspects of the disability tax credit (DTC). Its eligibility criteria are long and complex, making it difficult for most Canadians to understand this tax-delivered assistance and to determine whether they potentially could qualify for this measure. The complexities also present multiple challenges to health providers who are required to complete Form T2201.

Many of the concerns that were brought to the attention of the Committee and that we address in this report are not new. They have been raised over the years in numerous reports, including those produced by the House of Commons Sub-Committee on the Status of Persons with Disabilities, the Technical Advisory Committee on Tax Measures for Persons with Disabilities and, most recently, the Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology.

In addition to these reports, wide-ranging concerns were brought directly to our attention in the submissions we received from individual Canadians, organizations representing persons with disabilities and health providers who responded to the health provider survey that our committee conducted in June and July 2018.

The many eligibility complexities identified both recently and in years past can be grouped into five key themes:

- the definition of mental functions;

- the interpretation of marked restriction and the 90% guideline;

- parity in the treatment of physical and mental functions;

- life-sustaining therapy; and

- designated conditions.

Each of these issues is discussed below. Proposed improvements to various administrative procedures and CRA decision-making processes around DTC eligibility are considered in Section 3. We also note that a new challenge has arisen in recent years regarding the additional and vital role the DTC now plays as a gateway to other benefits. We discuss this emerging issue in Section 5.

Before we explore in greater depth each of the identified concerns, the Committee would like to acknowledge that we very much appreciate the challenges involved in the fair and consistent assessment of DTC eligibility. We know that this determination is no easy task.

We understand that in assessing eligibility for the DTC, the key criterion is not so much the presence of certain disabilities but rather the impact of these disabilities on the applicant’s day-to-day functioning. The person must be blind or be markedly restricted in at least one of the basic activities of daily living.

These basic activities of daily living are on the DTC application, Form T2201. They include vision, speaking, hearing, walking, eliminating, feeding, dressing and mental functions necessary for everyday life. The need for life-sustaining therapy as defined on Form T2201 also renders a person eligible for the DTC.

Because Form T2201 and the self-assessment questionnaire in Guide RC4064, Disability-Related Information, are the key sources of information to the public about the DTC, it is of utmost importance that these documents respect both the legislative intent of the Income Tax Act and its interpretation by the Tax Court of Canada.

We begin our discussion by focusing on the legislative intent of the DTC and the need for clarity in conveying this legislative intent. As noted, the effective administration of this intent and its clear communication by the CRA are considered in subsequent sections of this report.

Definition of mental functions

Perhaps no functional area in the DTC eligibility list has been fraught with more difficulty than mental functions. We are concerned both with how mental functions are defined in the federal Income Tax Act and how they are assessed on Form T2201.

As noted, the policy and administrative challenges with respect to the DTC treatment of mental functions are not new. They have been documented for close to 20 years.

The Sub-Committee on the Status of Persons with Disabilities held parliamentary meetings with representatives of health-related voluntary organizations as well as the Canada Revenue Agency and the Department of Finance Canada from November 2001 to February 2002. On March 21, 2002, the Sub-Committee tabled its report, Getting it Right for Canadians: The Disability Tax Credit, in the House of Commons.

When consultations with stakeholders failed to resolve major concerns with the administration of the DTC, the federal government created the Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) on Tax Measures for Persons with Disabilities in April 2003. While the TAC acknowledged the wide range of policy and administrative concerns linked to the DTC, it identified impairment in mental functions as the most difficult eligibility assessment challenge.

In the report, Disability Tax Fairness, published in December 2004, close to 15 years ago, the TAC made several recommendations to clarify the way in which mental functions were defined for the DTC proposing the following:

- changing "thinking, perceiving and remembering" in the Income Tax Act to mental functions necessary for everyday life in subparagraph 118.4(1)(c)(i) (recommendation 2.2); and

- providing for the cumulative effects of restrictions in more than one basic activity of daily living where the effects are equivalent to a marked restriction in a single basic activity of daily living in subparagraph 118.3(1)(a.1) and (a.3) (recommendation 2.4).

The TAC also recommended that the list of mental functions be expanded as it was deemed to be too narrowly defined:

"In our view mental functions are the range of processes that govern how people think, feel and behave. Based on our consultations and research, they include memory, problem solving, judgment, perception, learning, attention, concentration, verbal and non-verbal comprehension and expression, and the regulation of behaviour and emotions. These functions are necessary for activities of everyday life that are required for self-care, health and safety, social skills and simple transactions [TAC 2004: 122]."

The Income Tax Act subsequently was amended in 2005. Mental functions necessary for everyday life as set out in Form T2201 were changed to the following:

- adaptive functioning (for example, abilities related to self-care, health and safety, abilities to initiate and respond to social interactions, and common, simple transactions);

- memory (for example, the ability to remember simple instructions, basic personal information such as name and address, or material of importance and interest); and

- problem-solving, goal-setting, and judgment, taken together (for example, the ability to solve problems, set and keep goals, and make the appropriate decisions and judgments).

It is not clear how the federal government arrived at this interpretation of the TAC recommendations on the definition of mental functions. The changes that were introduced did not effectively capture the full intent of its proposals.

Data on the rate of DTC acceptance by function show that challenges in establishing eligibility for persons with disabilities related to mental functions continue to this day. The recent report of the Standing Senate Committee noted that:

"The approval rate for all new DTC applications processed ranged between 93% and 91% over the five-year period between 2011-2012 and 2015-2016. In 2016-2017, the approval rate for new applications declined to 89%.

Yet when the data were disaggregated by activity limitations, applications related to mental functions had consistently the lowest approval rates. Over the six-year period, applications related to mental functions had an approval rate ranging from 88% in 2011-2012 to a low of 81% in 2016-2017.

Applications related to the activities of dressing (often associated with pain and musculoskeletal disabilities) and feeding (a person requiring a feeding tube) consistently had the highest approval rates, ranging between 97% and 94% over the period. It is also noted that 2016 to 2017 appears to be an outlier year, with approval rates lower across all activity limitations, but most significantly for activities related to mental functioning [Senate 2018: 10]."

The data also reveal that while activities related to mental functioning have consistently lower approval rates, they represent the largest category of DTC claimants in five of the last six years (see Appendix 10).

In fact, the changes made to the Income Tax Act in 2005 ended up creating new problems that did not make the eligibility process any easier. For the purposes of establishing DTC eligibility, the assessment of persons with impairment in mental functions continues to be complex.

For one thing, the eligibility criteria for mental functions are conceptually confusing and are not clinically meaningful. We learned from the health provider survey that "while the effects of disability have to be unpacked in a way that the CRA understands, they are a bit foreign to a clinician geared more toward treatment." Another respondent told us: "I do not conduct diagnostic assessments with the purpose of filling out the CRA DTC form. This makes it difficult to comment on certain areas that CRA wants input on."

In fact, we note that the mental functions identified on Form T2201 are not all functions but represent, instead, a mix of functions and activities of daily living. Memory, problem solving, goal setting and judgment are all mental functions. Abilities related to self-care, and health and safety, by contrast, are activities.

We also question why three distinct mental functions must be present conjunctively. The Income Tax Act requires that problem solving, goal setting and judgment be "taken together," which means that a person must have a severe and prolonged impairment in all three mental functions to qualify for the DTC.

It makes no clinical sense to require that these three functions be present in combination in order to meet the eligibility criteria for the DTC. A person may have a severe and prolonged depression, for example, which compromises goal setting and judgment but not problem solving.

To add confusion, Form T2201 appears to contradict the conjunctive requirement. It acknowledges, through the following note included on the form, that problem solving, goal setting and judgment may be interpreted disjunctively: "A restriction in problem solving, goal setting or judgment that markedly restricts adaptive functioning, all or substantially all of the time, would qualify." At the very least, this contradiction must be resolved.

Our third concern: Requiring that problem solving, goal setting and judgment are present together applies a degree of rigour for mental functions that is not expected for the activities of daily living related to physical functions. It reflects a lack of parity between the treatment of impairment in physical and in mental conditions.

A person is deemed markedly restricted in walking, for example, if he or she cannot walk, regardless of cause. Factors related to memory, goal setting, judgment, problem solving, and learning can singly or in combination be responsible for a marked restriction in mental functions necessary for everyday life. Similarly, neurological factors, orthopedic factors and fatigue can singly or in combination be responsible for a marked restriction in walking.

However, if a health provider confirms that a person cannot walk, that individual is deemed eligible regardless of which, or how many factors, underlie the inability to walk. The same principle must, in all fairness, be applied to mental functions. If a person is markedly restricted in any of the mental functions necessary for everyday life, it should not matter which factor or combination of factors underlies the marked restriction.

The Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA) noted this problem in its submission to the Committee. "The way that ‘impairment’ is conceptualized for applications based on ‘mental functions necessary for everyday life’ creates, in comparison to the other categories on the T2201, a higher threshold for the individuals with mental health-related difficulties to qualify." Moreover, the CMHA points out that "people with mental health-related disabilities are especially vulnerable in this situation due to this array of factors in combination with ill-defined and inappropriate eligibility criteria in relation to mental illness."

In order to ensure equity in the treatment of applicants with impairment in physical functions and those with impairment in mental functions, we recommend:

That in the determination of DTC eligibility, the Canada Revenue Agency ensure that the principle of parity guides its actions with respect to physical and mental functions including, but not limited to, the removal of multiple screens of eligibility for persons with impairment in mental functions.

The current iteration of mental functions must not only be consistent with the treatment of impairment in physical functions. The list also needs to be clinically meaningful. If Form T2201 requires that a physician, nurse practitioner or psychologist attest to the nature and impact of an applicant’s impairment, then the criteria must be those routinely assessed as impaired for mental health conditions.

We heard from many providers who stated unequivocally that Form T2201 is totally inadequate when it comes to impairment in mental functions.

"The form has a medical orientation that seems to be more directed towards physical than psychological or neuropsychological disabilities."

"The category of mental health concerns is completely missing from this application. Individuals with neurodevelopmental disorders can have significant mental health problems which impact on functioning and there is no way to elaborate on this (in fact, it isn't even an option as everything is physical medicine-based in this application). For example, individuals with autism spectrum disorder may be extremely impaired in daily functioning, not due to a hearing impairment, but to the attentional processes that are required to 'tune in' to the environment. Or this same individual may be so overwhelmed from a sensory point of view that he is unable to ‘hear’ what he is supposed to be hearing (due to the inability to filter out extraneous noises)."

We recognize the challenges involved in defining mental functions. In a frequently cited Tax Court of Canada case Radage v. The Queen, former chief justice Donald G.H. Bowman set out a long and thoughtful discussion on the definition of mental functions as they were defined at the time. He pointed out the daunting complexity of mental functions and the multiple difficulties involved in trying to arrive at precise definitions of these terms [Radage v. The Queen 16].

We also note that several cases brought to the Tax Court of Canada have challenged the current definition of mental functions and its interpretation by the CRA. Most notable is the decision in Buchanan v. The Queen that was upheld by the Federal Court of Appeal, in Canada (Attorney General) v. James W. Buchanan.

Connections is an Alberta-based organization that supports individuals with cognitive disabilities. In its submission to the Committee, Connections pointed out that "many professionals believe that the DTC only applies to physical disabilities." It further noted that health providers often inform individuals with developmental disabilities that they do not qualify and the doctors or psychiatrists refuse to fill out the form.

The Canadian Mental Health Association pointed out in its submission that individuals with impairment in mental functions find that health providers lack clarity and understanding of the DTC eligibility criteria and are thus hesitant to complete the DTC form. Moreover, "the understanding of disability implicit in the T2201 overlooks many of the ADLs (activities of daily living) and functions that are impacted by mental health-related disabilities, such as lack of initiative or motivation or changed/unusual behaviour."

Our committee carried out, as noted, a survey of health providers to hear their views on the DTC and the challenges involved in assessing impairment in physical and/or mental functions. Respondents made clear that the eligibility criteria for mental functions, in particular, are not those routinely assessed nor are they helpful in determining which conditions would actually qualify for the DTC.

The understanding that some conditions may be categorically ineligible appears to abound among applicants, consumer groups and health providers even though, as mentioned, no condition other than blindness is categorically eligible and no condition is ineligible. The challenge for health providers is in understanding how markedly restricted the individual with an impairment in mental functions must be in order to be deemed eligible for the DTC.

Moreover, the survey noted uncertainties around a range of conditions including autism, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and schizophrenia. We heard, for example:

"It has been my experience that some clients who are much less impaired have received the credit and those who are more impaired have not. I do not know what I should be writing to ensure that my clients, many of whom have lifelong disabilities such as autism spectrum disorders, qualify."

"Because I am responsible for autism spectrum assessments, I am asked to complete them for my clients. I believe the CRA has not developed a clear understanding of how impairing the presentation is, even for high functioning individuals."

It is vital to pay attention to this feedback from health providers for whom the definition and identification of mental functions are core components of their professional expertise. These are the professionals who both develop and employ the taxonomies and diagnostic classifications of mental disorders.

We strongly urge the federal government to revise the DTC criteria related to mental functions. While there is no single commonly accepted list, there are important internationally recognized standards that can help shape a new definition of mental functions.

Our recommended reformulation of mental functions necessary for everyday life approximates two such taxonomies. We have integrated and simplified these internationally developed clinical lists into a more simple and practicable form necessary for DTC purposes.

We have reformulated the definition of mental functions based on two types of data sources:

- the international classifications from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the U.S.-based National Institute of Mental Health; and

- the feedback from more than 1,000 health providers who responded to our survey of their experience with Form T2201.

The WHO classification includes the following list of mental functions: attention, memory, psychomotor, emotional, perceptual, thought, higher level cognition, mental functions of language, calculation, mental function of sequencing complex movements, experience of self and time functions, and specific mental functions. Each of these, in turn, is broken down into specific components.

The U.S.-based National Institute of Mental Health also sets out a detailed list of cognitive functions, which include attention, perception, declarative memory, language, cognitive control and working memory. Each is described and disaggregated into its constituent components, where appropriate.

We have reformulated the definition of mental functions with these international classifications as the empirical base. We have also taken into account the recommendations of, and feedback from, clients and health providers. Our goal is to ensure that a revised list of mental functions is clearer, more consistent with clinical practice and more easily applied. We recommend:

That the Canada Revenue Agency amend the list of mental functions on Form T2201 as follows:

- attention;

- concentration;

- memory;

- judgment;

- perception of reality;

- problem solving;

- goal setting;

- regulation of behaviour and emotions (for example, mood disturbance or behavioural disorder);

- verbal and non-verbal comprehension; and

- learning.

In addition to reformulating the definition of mental functions, other administrative clarifications are required. In respect of the principles of simplicity and user friendly proposed by the Multiple Sceloris Society of Canada, we note three areas that need immediate attention.

First, the text box on page 5 of Form T2201 asks qualifying providers to describe the effects of the applicant’s impairment. We learned from submissions to the Committee, as well as the health provider survey, that the current wording on the form creates confusion. More specifically, it is unclear whether health providers are being asked to assess the actual impairment or its effects on the applicant’s functional capacity. In order to ensure clarity of interpretation, we recommend:

That the Canada Revenue Agency replace on page 5 of Form T2201 the term "effects of the impairment" with the following:

"The effects of the individual’s impairment must restrict their activity (that is, walking, seeing, dressing, feeding, mental functions, eliminating, hearing, speaking or some combination thereof) all or substantially all of the time, even with therapy and the use of appropriate devices and medication."

Second, Form T2201 itself is confusing to health providers in that it appears to provide contradictory information. In order to rectify this problem, we recommend:

That the Canada Revenue Agency delete the reference to "social activities" on page 5 of Form T2201 due to the contradiction on page 3 of the form. Page 5 states that one is ineligible on the basis of social and recreational activity, while page 3 states that the inability to initiate and respond to social interactions makes one eligible, as does the inability to engage in common simple transactions.

Third, there is confusion about the question on page 5 of Form T2201 that asks health providers about the likelihood of improvement. It is not clear if the CRA is asking whether the underlying condition is likely to improve or whether the individual’s functional capacity is expected to improve. In order to clarify the intent of the question, we recommend:

That the Canada Revenue Agency change the question on page 5 of Form T2201 about the likelihood of improvement to ask health providers whether the individual’s illness or condition that is responsible for the impairment in function, such as walking or cognitive functions, is likely to improve, as in the following example:

"In thinking about the individual’s impairment, please consider whether the condition that causes the impairment (for example, blindness, paraplegia, schizophrenia or bipolar disorder) can be expected to last for a continuous period of at least 12 months."

The introduction of a clearer and clinically valid definition of mental functions is a vital start. But it is only a start. The other equally difficult roadblock comes in the form of the criteria employed by the CRA to assess the impact of the impairment on physical and/or mental functions.

Marked restriction and the 90% guideline

In order to qualify for the DTC, the presence of impairment is not sufficient. The effect of the impairment in physical and/or mental functions must be severe and prolonged.

As noted in the first section, DTC eligibility requires that an applicant meet one of the following criteria:

- is blind;

- is markedly restricted in at least one of the basic activities of daily living;

- is significantly restricted in two or more or the basic activities of daily living (can include a vision impairment); and

- needs life-sustaining therapy.

In addition, the person’s impairment must meet all of the following criteria:

- is prolonged, which means the impairment has lasted, or is expected to last for a continuous period of at least 12 months; and

- is present all or substantially all the time (at least 90% of the time).

Applicants are considered markedly restricted if they are unable or take an inordinate amount of time to do one or more of the basic activities of daily living, even with therapy (other than life-sustaining therapy) and the use of appropriate devices and medication. This restriction must be present all or substantially all the time, which has been interpreted by the CRA as at least 90% of the time.

The CRA defines inordinate amount of time as a clinical judgment made by a health provider who must attest to the fact that three times the average time is needed to complete the activity by a person of the same age who does not have the impairment. We heard that there is confusion in this area and that "it is difficult to differentiate between markedly and significant."

The most problematic area arises around the interpretation of the all or substantially all of the time requirement. It has been administratively interpreted by the CRA to mean that the restrictions in activity are present at least 90% of the time. When the individual’s ability to perform a designated activity is not restricted for at least 90% of the time, the CRA may determine that the applicant is not markedly restricted all or substantially all of the time.

Since the mid-1990s, the CRA has interpreted the all or substantially all of the time clause in the Income Tax Act as being at least 90% of the time. It has applied this guideline in various contexts, including businesses and charitable activities. The CRA argues that it uses this interpretation according to the well-established principle of uniformity of expression. In other words, the same term in the Income Tax Act has the same meaning throughout the Act unless a different meaning is clearly indicated.

In 2012, the CRA revised Form T2201 by introducing the parenthetical notation of the mathematical model to describe all or substantially all of the time as being at least 90% of the time. It is of interest that there was a significant uptick in refusals in DTC eligibility in 2012. We believe that this increase was due to the explicit reference to the 90% guideline on Form T2201.

We have serious difficulties from two perspectives in the use of the 90% guideline as it applies to the DTC. First, it has no basis in law. Second, its use has been challenged by relevant jurisprudence.

From a legal perspective, the 90% interpretation has no basis in actual law. The Income Tax Act does not establish a numeric or percentage calculation for the meaning of all or substantially all of the time.

From a judicial perspective, the use of the 90% guideline as applied to mental functions in the context of the DTC, in particular, has been challenged in several judgments prepared by the Tax Court of Canada.

The problem is that the 90% guideline has created an insurmountable barrier for many individuals living with severe and chronic impairment in mental functions as well as those with fluctuating or episodic conditions, such as multiple sclerosis. In Philip Steele v. the Queen (Docket: 2001-3700-IT-I), Judge Campbell Miller addressed the fact that a mathematical model is not an appropriate measure of disability for people living with mental disorders:

"I remain just a bit sceptical that the medical profession has advanced to the point that the complexities of the brain's receipt, storage and retrieval of data can be identified with such an accuracy that would allow a psychiatrist to proclaim that an individual is unable to remember 25%, 50% or 90% of the time."

The Honourable Donald G.H. Bowman, former chief justice of the Tax Court of Canada, has ruled against the CRA's interpretation of all or substantially all of the time as being at least 90%. In Watts v. The Queen and in several other cases, the judges noted that the 90% rule has no statutory basis.

In our interpretation of these court cases, the Committee believes that even if it had some basis in law, the rule itself is defective because it leaves unanswered the question 90% of what? While the 90% rule of thumb may be convenient to assessors and tax advisors, it is difficult to apply in practice.

The Disability Tax Fairness Campaign reviewed the court case of Bruno Maltais v. The Queen and indicated that Judge Alain Tardiff recognized that individuals living with psychotic illnesses did not exhibit the associated symptoms continuously. The judge stated that:

"When the problem involves a mental disability, the exercise is much more difficult and complicated, since the outward signs are not always visible or apparent. Moreover, a person who has such a disability may break down at any time without there being any indications or warning signs."

In a submission to the Committee, the Canadian Mental Health Association noted that because the experience of mental illness is frequently an episodic and variable one, the current DTC eligibility guidelines are inappropriate for mental illness. The CMHA proposes that the CRA "revise the language around ‘all or substantially all of the time’ as well as the 90% threshold as eligibility criteria."

In fact, the data for the fiscal year 2016 to 2017 demonstrate just how difficult it has become for people living with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and other psychotic disorders to access the DTC, even those who have been receiving the tax credit for 10, 20 and even more years and their condition has remained unchanged. The unprecedented 53% increase in the number of rejections of applications from people who are markedly restricted in their mental functions all or substantially all of the time needs to be addressed [Lembi Buchanan].

We note, however, that persons with impairment in physical functions are equally vulnerable. The Chronic Pain Association of Canada pointed out to us that chronic pain can be invisible, even to clinicians. As a result, both acute and chronic pain are outright dismissed.

The National ME/FM Action Network, which represents the concerns of Canadians with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome, identified similar challenges. Its submission calls for a fundamental review of the current eligibility criteria and the addition of a new activity of daily living to deal with reduced functional capacity. Energy or pain impairments should be recognized among the eligibility criteria. The network notes explicitly that the "90% of time phrase is confusing."

The cases involving conditions in which symptoms present themselves intermittently have proven to be particularly challenging. While the symptoms may be intermittent, the condition is ever-present. It may impair the ability to carry out the basic activities of living at any time.

In its brief to the Committee, the Multiple Sceloris Society of Canada pointed out that the unpredictable, episodic and progressive nature of multiple sclerosis makes it challenging to maintain an adequate quality of life. Qualifying for income and disability programs is difficult for individuals with MS due to the episodic nature of the disease. Periods of good health are interrupted, often unpredictably, by periods of illness or disability that affect functional capacity.

The Multiple Sceloris Society recommends that the definition of disability used in determining eligibility for the DTC be changed to take into account all individuals with disabilities, including those with episodic disabilities. The Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology documented similar concerns about the eligibility barriers encountered by Canadians with fluctuating or episodic disabilities. It noted in its Breaking Down the Barriers report:

The committee also heard about the significant barriers that people living with episodic disabilities such as Multiple Sclerosis (MS) experience when trying to access the DTC. At present, a person’s disability must last for a continuous period of at least 12 months. This is problematic for people with chronic diseases that present episodic symptoms. For example, MS is a chronic, degenerative disease with no known cure. Symptoms can come and go unpredictably, being very severe and debilitating at some times and then abating for periods of time. The current criteria for the DTC do not capture the reality of those living with unpredictable, episodic experiences of disability, even though they face the same higher costs of living, economic challenges and income insecurity [Standing Senate Committee 2018: 11].

Committee member Lembi Buchanan presented to the House of Commons Standing Committee on Human Resources, Skills and Social Development and the Status of Persons with Disabilities that imposing the inflexible 90% guideline has created an insurmountable barrier for many individuals living with severe and prolonged impairments in mental functions and episodic disabilities. Many have reported that their doctors refuse to complete Form T2201, even though they may have qualified in previous years. The Chronic Pain Association of Canada raised a similar concern.

Respondents to the health provider survey also told us that:

"The 90% impairment is very hard to understand because a person with autism has the condition 100% of the time, but apparently it isn’t impairing enough in some cases but it is in others. It seems that a different form is needed for dealing with psychological issues - the way to report doesn’t fit with the medical aspects of the form."

"My clients often have developmental disorders that may fluctuate depending on the circumstances around them. It is difficult for me to determine whether their impairments will actually be present "90%" of the time, and the potential for them to be present is 100% of the time."

"90% of the time is difficult to ascertain and it is difficult to determine the extent of the effects of mental health disorders. The (T2201) form seems more suited for medical conditions and not mental health conditions."

Our committee believes strongly that the eligibility criteria regarding the assessment of severity of impairment in mental functions must be clarified. For one thing, Form T2201 asks health providers to identify when the individual’s restriction in mental function(s) became a marked restriction. It should made clear that this question does not necessarily refer to the year of the diagnosis, but to the time when the diagnosed condition produced severe and prolonged impairments in mental functions as defined by Form T2201.

The Committee spent considerable time discussing the problems related to the 90% guideline. Our deliberations led us to oppose the application of a fixed numeric standard for DTC eligibility. While a percentage guideline may readily apply to banking and other fixed assets, it is impossible to fairly and effectively employ a numeric benchmark in the determination of functional impairment. The application of a uniform blanket rule makes no sense when it comes to assessing complex human behaviour.

Based on our review of cases of appeal, as well as on a deeper understanding of how impairments impact functioning across functions, we propose that the CRA no longer interpret all or substantially all as 90% of the time and no longer interpret an inordinate amount of time as three times the amount of time it takes a person without the impairment. The reason for this recommendation is that, upon appeal, the courts have taken the position that there is no basis for these interpretations of terms in law.

More importantly, the threshold of 90% or three times the amount of time is too high a bar for persons who are indeed markedly restricted by their impairments. A restriction that is present 50% of the time may be marked. For example, if half the time one is unable to navigate directions or dress oneself, especially if those times are unpredictable, the impact on a person’s functioning is as severe as if the restriction were present 90% of the time. We recommend:

That the Canada Revenue Agency no longer interpret all or substantially all as 90% of the time and no longer interpret an inordinate amount of time as three times the amount of time it takes a person without the impairment;

That in the DTC assessment process, the Canada Revenue Agency employ the following definition to determine marked restriction in mental functions:

"The individual is considered markedly restricted in mental functions if, even with appropriate therapy, medication and devices (for example, memory and adaptive aids):

- all or substantially all the time, one of the following mental functions is impaired, meaning that there is an absence of a particular function or that the function takes an inordinate amount of time:

- attention;

- concentration;

- memory;

- judgment;

- perception of reality;

- problem solving;

- goal setting;

- regulation of behaviour and emotions (for example, mood disturbance or behavioural disorder);

- verbal and non-verbal comprehension; or

- learning; OR

- they have an impairment in two or more of the functions listed above none of which would be considered a marked restriction all or substantially all the time individually but which, when taken together, create a marked restriction in mental functions all or substantially all the time; OR

- they have one or more impairments in mental functions which are:

- intermittent; AND/OR

- unpredictable; AND

- when present, constitute a marked restriction all or substantially all the time."

Form T2201 asks health providers whether the applicant is markedly restricted in performing designated activities related to mental functions. We believe it would be helpful to provide examples that can act as guidelines for health providers in making this determination. Many of the comments from the health providers survey support this view. We heard:

"It would be better if there were more options/examples on the form and if we could use check-boxes rather than text description. Somewhere on the CRA website, it would be useful to have examples of patients who don’t meet the criteria as well as those that do to give more education to those of us who have to complete these forms."

Our committee agrees that examples are particularly important in the case of impairment in mental functions around which there have been so many challenges in establishing eligibility. We recommend:

That the Canada Revenue Agency remove specific references to activities in the T2201 section on mental functions and include examples of activities in the current Guide RC4064 to help health providers detail all the effects of the markedly restricted mental function(s), as in the following illustration:

"The individual is considered markedly restricted in mental functions if they have an impairment in one or more of the functions all or substantially all of the time or takes an inordinate amount of time to perform the functions, even with appropriate therapy, medication, and devices. The effects of the marked restriction in mental function(s) can include, but are not limited to, the following (this list is illustrative and not exhaustive):

- with impaired memory function, the individual cannot remember basic information or instructions such as address and phone number or recall material of importance and interest;

- with impaired perception, the individual cannot accurately interpret or react to their environment;

- with impaired learning or problem solving, the individual cannot follow directions to get from one place to another or cannot manage basic transactions like making change or getting money from a bank;

- with impaired comprehension, the individual cannot understand or follow simple requests;

- with impaired concentration, the individual cannot accomplish a range of activities necessary to living independently like paying bills or preparing meals;

- with impaired ability to regulate mood (for example, depression, anxiety) or behaviour, the individual cannot avoid the risk of harm to self and others or cannot initiate and respond to basic social interactions necessary to carrying out basic activities of everyday life; or

- with impaired judgment, the individual cannot live independently without support or supervision from others or take medication as prescribed."

As we note in the recommendation, these examples are illustrative only and are not meant to be exhaustive. The Multiple Sceloris Society of Canada brought to our attention the fact that "some individuals and/or qualified practitioners look at the examples on the form and don’t necessarily think outside of the examples indicated."

Several respondents to the health provider survey identified another serious weakness in the DTC eligibility process. The current Form T2201 does not readily apply to children because they typically require assistance with most of the activities of daily living. It was felt that examples would help health providers distinguish between a disability-related limitation and a developmentally related limitation due solely to age and maturation.

We concur that examples can act as invaluable guidelines to practitioners. We believe that the CRA should include some examples that are relevant to health providers completing Form T2201 on behalf of children. Because Form T2201 is geared toward adults, young children would need a lot of assistance from parents in the criteria currently listed. Several health providers commented on this concern:

"The questions are also difficult to apply to young children with diagnoses of developmental/intellectual disability. The activities of daily living are barely learned at a young age, and therefore cannot be depicted as impaired. But we know clinically that they WILL BE impaired in the future."

"The form was mostly created for adults. Many sections do not apply to pediatric patients, especially children who have never developed and will never develop the ability to take care of themselves. Having criteria more specific for children would make the form a lot more relevant."

"The criteria are difficult to apply to children. Normal children cannot do most activities listed, hard to use the form to explain the limitations of the children. Families read the forms and say their children with conditions like ADHD (attention deficit hyperactivity disorder) should meet the criteria under mental function, but in my opinion the child requires the same assistance as any child that age. I'd love to see a pediatric specific section for kids who require extra assistance for motor skills/extra supervision due to flight risk/self-harm."

"There are incidents when infants with genetic abnormalities require a lot of extra attention between specialist appointments and added therapies. The questions (on Form T2201) are irrelevant for an infant as they are dependent. Questions such as can they toilet themselves and feed themselves do not apply to an infant but there is a definite need with the extra time and expenses required to attend to the infant’s special needs."

"I would recommend that adults and children not be lumped together in terms of what constitutes impaired functioning as their day to day reality is definitely not the same – e.g., school vs work settings."

"It is ABSOLUTELY impossible to fill out this form for children with autism and other developmental disorders. Sounds like the people who designed this form forgot about these kids....!!!"

"This form is not well laid out for pediatricians, especially pediatricians seeing younger children with developmental disorders. I am a developmental pediatrician, specializing in developmental disorders and my focus is on developmental delays (genetic disorders, intellectual delays, global developmental delays) and autism, though I do see some children with neuromotor disorders, such as cerebral palsy. I often receive back the secondary forms for young children under 5 years with global developmental delays and very low DQ's (developmental quotients) - i.e., DQs<55 as well as on children with autism. The questions related to the independent functioning (dressing, eliminating, feeding) are not applicable because of their age, and the term ‘mental functions for everyday life’ is poorly worded for young children and for their parents to read."

In order to address the multiple challenges related to completing Form T2201 for children, the Committee recommends:

That the Canada Revenue Agency consider a child and an adult version of Form T2201, with eligibility criteria tailored as necessary.

We recognize, however, that it would take time to develop a new form for children and that legislative underpinnings would need to be introduced for this reform. In the meantime, we urge the CRA to expand the list of guidelines for health providers to include examples that apply to children. This action would at least respond to the concern we heard that "clearer guidelines for parents with children with disabilities are a must." The examples should include behaviours related to developmental disabilities and autism.

Parity between physical and mental functions

We have already expressed our concern about the fact that the current eligibility DTC requirements as presented on Form T2201 set the bar higher for mental functions than they do for physical functions. In an earlier recommendation in this section, we called for parity in the treatment of mental and physical functions. The lack of parity is compounded by the fact that some of the activities of daily living on Form T2201 are indeed activities (for example, dressing, feeding) and others are functions (for example, walking, seeing). The successful completion of an activity depends on any number of biological, social and psychological functions.

In order to respect the parity principle, we believe it is necessary to make associated changes in the statement of functions. We recommend:

That the Canada Revenue Agency revise the list of functions on Form T2201 to the following:

- vision;

- speaking;

- hearing;

- lower-extremity function (for example, walking);

- upper-extremity function (for example, arm and hand movement);

- eliminating;

- eating/feeding; and

- mental functions.

That the Canada Revenue Agency, in respect of the parity principle, create a list of examples of activities for each impaired function for inclusion in the current Guide RC4064 to help health providers detail all the effects of markedly restricted function(s), as in the following proposed guidelines (this list is illustrative and not exhaustive):

- with impaired lower-extremity function, the individual cannot walk;

- with impaired upper-extremity function, the individual cannot feed or dress themselves, or cannot attend to basic personal hygiene; or

- with impaired eating/feeding, the individual cannot swallow or eat food.

As in the case of mental functions, the examples here are illustrative only and can be expanded. In addition, the list should include examples that apply to children.

In fact, we heard that it would be important to engage professionals designated for each area of functioning to create the questions that need to be asked to determine level of impairment. Form T2201 was created many years ago for specific disabilities. While it has been expanded to include a range of disabilities, it has not been tailored to them. Further, in our view, there has been insufficient reliance on the health provider community in defining and administering the eligibility criteria and communicating these on Form T2201.

The health provider survey also brought to our attention the fact that the screening criteria for some physical functions are confusing or out of date. For example, we heard the following:

"The wording of the questions related to ‘speaking’ is poor. Questions are geared only towards speaking and don’t take into account language. Communication involves the actual speech act (i.e., ‘speaking’) but also includes the ability to use and understand language (i.e., to be able to put together and understand grammatical sentences)."

"When asking whether someone is ‘markedly restricted in speaking because they are unable to or takes an inordinate amount of time to speak,’ it does not take into account individuals with a severe expressive language delay. Someone with a moderate intellectual delay and an expressive/receptive language delay would not qualify based on the wording of this question, when they definitely should. Someone may be able to speak clearly but the content of what they say and what they are able to understand is severely delayed."

"At present, the form suggests that the person must be ‘unable to speak’ or ‘take an inordinate amount of time to speak’ in order to qualify. Does this mean we should only consider clients who lack the ability to speak or have a ‘reduced rate’ of speech? What about clients who have significant difficulty understanding language? Does the wording you use mean we shouldn’t consider clients that have overall difficulty with speech and language (e.g., clients who have significant issues with speech intelligibility, clients with significant issues with social communication skills, clients with severely disordered voice)? It might make more sense to use terminology that describes the severity of the overall speech-language disorder (e.g., ‘significantly or severely disordered/delayed speech or language skills’) if that is the intent of the form.

"It is not clear that a cumulative assessment can be used and that this can include vision. I also think that it should be clear that other aspects of vision (most importantly contrast sensitivity) can (should) be taken into account as well as visual acuity and visual fields, and that the impairment from all measures of vision (visual acuity, fields and contrast sensitivity) should be considered in an additive way. There should be a specific place to indicate this."

The Committee learned as well that the screening criteria for hearing are no longer current and need to be updated. We recommend:

That the Canada Revenue Agency review the current eligibility criteria for hearing, which are out of date.

In summary, we strongly support the need to modify the eligibility criteria for mental functions, in particular, and for physical functions in order to ensure both the clinical relevance and conceptual coherence of the DTC eligibility process. We want to prevent, however, the problem that arose in the past in which the recommendations of the TAC were changed significantly upon their adoption into the Income Tax Act. In order to avoid a similar problem in future, we recommend:

That the Canada Revenue Agency work in collaboration with the Department of Finance Canada to consult with relevant health providers and stakeholders before introducing any legislative changes to the Income Tax Act with respect to the definition of mental or physical functions.

Life-sustaining therapy

Currently, applicants are potentially eligible for the DTC if they require life-sustaining therapy. A medical doctor or nurse practitioner must certify that the following two conditions are met.

First, an individual must require this therapy in order to support a vital function. This condition applies even if the therapy has eased the symptoms. Second, the applicant must require this life-sustaining therapy at least three times a week and for an average of at least 14 hours per week.

There are rules that apply to the 14-hour requirement. It includes only the time related to the actual therapy. The requirement assumes that people must take time away from their normal everyday activities in order to receive it. The time may also be spent on administering the life-sustaining therapy to a child.

However, the 14-hour time requirement excludes the time involved in several key activities:

- actions related to dietary restrictions or regimes, like counting carbohydrates or exercising, even when these activities may affect or determine the daily dose of medication;

- travel time to receive therapy or medical appointments not related to the life-sustaining therapy; and

- recuperation after therapy.

Several concerns regarding the eligibility criteria for life-sustaining therapy were brought to our attention. Perhaps most important, there are serious questions about the empirical basis for the 14-hour minimum weekly time requirement, in particular.

Our understanding is that the 14-hour condition originally was based on the estimated number of hours involved in weekly dialysis, a clearly recognized life-sustaining therapy. Dialysis treatment typically takes place three times a week for a minimum of four hours per session.

But the three-times per week and 14-hour requirement that comprise the DTC eligibility criteria are not necessarily appropriate for other treatments, even those that would qualify as life-sustaining in their purpose and their effect.

Moreover, an individual may have to receive life-sustaining therapy three times a week, but not necessarily for 14 hours a week. Our committee agreed that even 10 hours a week was a significant amount of time to devote to this purpose. Instead of requiring an account of the number of times and hours per week involved in this therapy, we agreed that the person who requires life-sustaining therapy will, by definition, automatically spend an inordinate amount of time receiving that therapy.

We heard in submissions to the Committee that the combined time requirement in terms of both minimum number of hours and weekly sessions has had the effect of excluding many applicants who receive life-sustaining therapy. They typically must spend a significant amount of time engaged in administering and/or receiving the life-sustaining therapy but not necessarily in the precise numeric requirements set out in Form T2201.

We also heard from many health providers in response to our survey that they simply are not in a position to verify the precise number of hours that an individual was engaged in a particular life-sustaining therapy. The fact that a person requires such therapy effectively means that they are spending an inordinate amount of time engaged in this activity.

"I complete DTC for patients with diabetes. The 14-hour rule does not really apply to patients with diabetes. Although they are essentially completing or planning in advance for tasks, illness, food, physical activity, changes in schedule constantly when they have type 1 diabetes. Persons living with type 1 diabetes should have a separate section to fill out in place of the 14 hours rule."

"I could not be confident that what I thought was a clear description of a disabled child would be seen as such by CRA, based on supplementary questionnaires I have received in the past. Some requirements, for example, documentation of 14 hours/week for life-sustaining therapy in type 1 diabetes, seems unreasonable. Additionally, there is pressure from families whose children do not appear to meet criteria, to complete the form indicating that the child is disabled; I would like the families to be able to clearly interpret the requirements for themselves."

Cases involving diabetes have been particularly problematic. Diabetes Canada pointed out that "the eligibility criteria as currently interpreted do not reflect the realities of administering life-sustaining insulin therapy." Living with diabetes is a 24-hour a day job. There are no days off and no vacation. It is a life-long balance of diet, exercise, blood sugar testing and medications. Yet the DTC has been severely limited for persons living with diabetes who require intensive insulin therapy, which includes:

- insulin administration by injection or pump;

- testing blood or interstitial fluid (CGM);

- matching insulin to food;

- adjusting dose of insulin for activity/illness/stress; and

- treating low blood sugars (hypoglycemia).

In 2017, Diabetes Canada and the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation became aware of an increased number of rejected DTC applications by people living with diabetes. These rejections included individuals who had been DTC-eligible for many years, but were now being turned down when their DTC eligibility came up for renewal.

The Standing Senate Committee also expressed concerns about this issue in its recent report:

"It was explained that persons with the same disability share similar health burdens and financial challenges regardless of the time required. For example, someone managing Type 1 diabetes experiences the same activity restrictions and higher costs associated with administering insulin regardless of whether it takes 10 hours or 14 hours per week. It was also noted that these rules can often mean that young adults cease to qualify for the DTC when they turn 18 simply because their parent’s time is no longer included in the amount of time spent administering a therapy. In reality the only thing that has changed is that the person has turned 18 [Standing Senate Committee, 2018]."

In light of all the submissions, survey reports and personal letters from applicants, our committee feels that the CRA must move away from a rigid definition and interpretation of life-sustaining therapy that excludes many potential eligible Canadians from qualifying for the DTC. The undeniable fact is that any individual who requires life-sustaining therapy, by definition, must administer therapies on a daily/weekly basis or they will not survive.

Although therapies are measurable, this is not only time consuming for the health provider, it is also costly to the individual and a challenge for CRA officials who interpret Form T2201, often resulting in clarification letters and appeals. In the case of type 1 diabetes, many individuals administer their therapies independently but would not be alive if they neglected these activities. Our committee strongly believes that in order to qualify for the DTC, this particular category could be simplified by establishing the fact that since the person is alive, they must be adhering to the therapies essential for survival.

Our committee had extensive debates about the therapies that potentially would qualify as life sustaining. We agreed that these would not include, for example, a prescription drug regime for cancer patients or an implanted pacemaker for cardiac patients. Life-sustaining therapies involve the application of a procedure on a regular and frequent basis over an extended period for the duration of a person’s life. Only a handful of life-sustaining therapies meet these criteria. We recommend:

That the Canada Revenue Agency replace the current eligibility criteria for life-sustaining therapies as set out in Form T2201 with the following:

Individuals who require life-sustaining therapies (LSTs) are eligible for the DTC because of the time required to administer these therapies. These are therapies that are life-long and continuous, requiring close medical supervision. Without them, the individual could not survive or would face serious life-threatening challenges. Close medical supervision is defined as monitoring or visits, at least several times annually, with a health provider. These therapies include but are not necessarily limited to: intensive insulin therapy for type 1 diabetes; chest therapy for cystic fibrosis; renal dialysis for chronic and permanent renal failure; and medically prescribed formulas and foods for phenylketonuria (PKU).

Designated conditions

In trying to ease eligibility through improved eligibility criteria, we discussed whether it would be helpful to include a statement of condition or diagnosis on Form T2201. While the decision would not be made the basis of diagnosis, at least an indication of diagnosis might be helpful to CRA assessors making eligibility determinations.

We acknowledge the pitfalls associated with this approach. A designated list in any area of public policy invariably raises questions of fairness about the groups, items or conditions that have been left out. A lobbying process typically begins to open up the list in order to make it more comprehensive and complete.

At the same time, however, we recognize that the inclusion of diagnosis, though not the primary determining factor, may ease DTC eligibility for many Canadians. While it would not be the primary consideration in any eligibility determination, it could help provide additional context to the assessment process. This substantiating information may reduce the time involved in decisions and the associated administrative costs.

There is precedent for the inclusion of diagnosis on the eligibility forms of selected programs. For example, the Government of Ontario includes in its eligibility for long-term social assistance, the Ontario Disability Support Program (ODSP), a set of prescribed classes.

Prescribed classes refer to specific categories of people who do not have to go through the disability adjudication process in order to qualify for ODSP income support. However, individuals in the prescribed classes must still apply and meet all other ODSP eligibility requirements. (It should be noted that the Government of Ontario recently announced a review of its ODSP eligibility criteria. The intent is to align these criteria more closely with federal guidelines.)

For the purposes of the ODSP, members of prescribed classes include persons who:

- receive Canada Pension Plan / Quebec Pension Plan disability benefits;

- are already determined eligible for services, supports and funding under the Services and Supports to Promote the Social Inclusion of Persons with Developmental Disabilities Act, 2008;

- reside in a home under the Homes for Special Care Act; or

- reside in a facility that was a former provincial psychiatric hospital.

Long-term social assistance in Alberta employs a similar approach known as straightforward medical adjudication. Under the Assured Income for the Severely Handicapped (AISH) program, straightforward medical adjudication is employed to streamline the application process when the applicant’s medical situation may not require extensive analysis. Examples include:

- palliative or terminal prognosis;

- awaiting organ transplant;

- tetraplegia; and

- severe brain injury.