2022 Third Annual Report of the Disability Advisory Committee

Table of Contents

- Recommendations at a Glance

- Part 1: Achievements to Date

- Part 2: DTC Eligibility

- Part 3: Ongoing Committee Work

- Part 4: Indigenous Issues

- Part 5: DTC Data

- Part 6: Registered Disability Savings Plans

- Appendices

- Appendix A: Terms of Reference

- Appendix B: Committee Members

- Appendix C: Committee Recommendations

- Appendix D: Federal Measures for Persons with Disabilities

- Appendix E: Disability Measures Linked to DTC Eligibility

- Appendix F: DTC Application Form T2201

- Appendix G: Resources on Language and Disability

- Appendix H: Selected Legal Issues

- Appendix I: Canada Disability Benefit

- Appendix J: Factsheet – Indigenous Peoples

- Appendix K: Updated Tables for the DTC Statistical Publication

Recommendations at a Glance

Third Annual Report of the Disability Advisory Committee

The Disability Advisory Committee (DAC) provides advice to the Minister and the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) on improving the administration and interpretation of tax measures for Canadians living with disabilities.

Our third report summarizes our work, the progress of previous recommendations, and provides the following 10 new recommendations:

Disability Tax Credit (DTC) Eligibility

1. The CRA and the Department of Finance Canada should change the term ‘impairment’ to ‘limitation’ in all DTC-related administrative and legislative documents.

2. Decisions to expand the pool of health providers, one provider group at a time, who can complete the DTC application form (T2201) take time and expertise that neither CRA nor the Department of Finance Canada possess.

3. Any licensed health provider, whose license is in good standing, be permitted to complete the DTC application (Form T2201).

4. The CRA should replace the current eligibility criteria for life-sustaining therapies as set out in the DTC application (Form T2201) with a designated list of identified therapies.

DTC Review and appeals

5. CRA to share DTC appeals data with the Committee to better understand which demographic groups are experiencing challenges.

6. The CRA should better communicate to DTC applicants who launch an objection or appeal, that they will remain eligible for all DTC-related benefits and credits until the appeal is resolved.

DTC Legal issues

7. The Department of Finance Canada should amend the Income Tax Act (ITA) and/or the CRA amend its policy, to allow a person with a mental disability to appoint a representative to manage their tax affairs without resorting to legal guardianship.

8. Over the long-term, the federal government should apply the Peace, Order and Good Government clause to encourage the creation of a national minimum-standard legislative framework for supported decision-making laws.

9. The CRA encourage the Department of Finance Canada to exempt DTC beneficiaries from the capital gains on the sale of a home entrusted to them.

10. The federal government broaden the list of persons defined as “qualified family member” in the ITA to include siblings to act as RDSP plan holders for persons with mental disabilities.

Part 1: Achievements to Date

Context

In 2017, Minister of National Revenue Diane Lebouthillier announced the creation of the Disability Advisory Committee to provide advice on tax measures for persons with disabilities. Since our first meeting as a group in 2018, we have covered a wide range of issues. Our mandate and current membership can be found in Appendices A and B, respectively.

In our two previous reports, we made a combined total 50 recommendations for improving disability tax measures in Canada. This third annual report adds another 10 recommendations to the list. Appendix C includes the full list of earlier and new recommendations.

Disability tax credit

While there are several tax measures intended specifically for persons with disabilities (Appendix D), the Committee focused our work this past year primarily upon the disability tax credit, commonly known as the DTC.

The DTC plays a significant role in the disability landscape. While the credit itself is not an income program, it has a major impact on income security in two ways:

- it reduces the amount of income taxes that persons with severe and prolonged disabilities must pay

- it acts as an entry point or gateway to other disability-related benefits and programs (Appendix E)

Individuals may apply for this credit for one or both of these purposes. For some applicants, the DTC acts only to reduce the amount of income taxes they owe. These individuals may not be eligible for or require any of the other programs linked to this credit.

Other applicants, by contrast, do not have sufficient taxable income and they owe little or no income tax. However, they apply for the DTC in order to establish eligibility for the related programs.

Finally, some Canadians may apply for the DTC for both purposes: to reduce their income taxes and to gain access to other benefits.

Needless to say, the dual role of the DTC adds a layer of complexity that is unique to this tax measure. It is difficult to explain this double purpose, which affects both income taxes and income levels of recipients.

This dual role seems to have evolved for a good reason. Prior to 2008, the disability tax credit acted only to reduce income taxes. When the Registered Disability Savings Plan (RDSP) was introduced in 2008, the Department of Finance Canada made the decision to use the DTC as the eligibility criterion for opening an RDSP account.

The decision made sense at the time. The rationale was to reduce the application burden by requiring persons with disabilities to go through a single eligibility process. There appeared to be a need for a single-entry point to the suite of federally-delivered programs and benefits. Using the DTC as a gateway to the RDSP helped reduce red tape as well as the time and costs involved in applying for the new program.

Over the years, the so-called gateway role of the DTC evolved to include access to a number of other disability-related programs. While there are many advantages to this approach, there are also clear disadvantages. If an applicant is refused at the single-entry point, there is nowhere to turn – other than to a review or appeals process.

The alternative is to have applicants qualify over and over again for every program for which they potentially are eligible. That process represents a heavy administrative burden, the costs of which would be better applied to the programs themselves. It is always best to minimize, to the extent possible, the administrative burden by simplifying various eligibility procedures.

But herein lies another challenge. The application process for the DTC is anything but simple and it involves a significant administrative apparatus. DTC applicants must complete the Disability Tax Credit Certificate (Form T2201) and a designated health provider must attest to the type and extent of disability related to the DTC claim.

The complexities involved in the DTC application process have given rise over the years to multiple committees and reports about the problems embedded in this process and the need for reform. Our Committee studied these various reports. In 2018, we carried out a pan-Canadian survey of health providers qualified to complete the T2201 to which we received more than 1,100 responses. Through our DAC portal, we heard from disability organizations and individual Canadians who described their lived experience.

Based on this evidence and our discussions, the Committee made DTC-specific recommendations in our two previous annual reports that pertained to three distinct areas:

- eligibility criteria

- administrative procedures for approving or denying claims

- communication and outreach for conveying information about this tax measure

We are pleased to present brief highlights of several legislative, administrative and communication reforms that have been introduced as a result of our work. At the same time, we acknowledge that significant challenges remain, which are discussed in the next sections of this report.

Key achievements

i. Legislative changes

Our first two annual reports described at length our many concerns about the DTC eligibility criteria. We identified multiple problems related to the list of functions as set out on the application Form T2201.

We were particularly concerned about the definition of mental functions. For one thing, some of the defined impairments in mental functions had to all be present in order to qualify under mental functions. We noted that this conjunctive requirement did not apply to any of the physical functions. It effectively meant that a higher eligibility bar was being applied to the mental functions category. Moreover, the list of mental functions was an odd combination of functions and activities of daily living.

The conjunctive requirement, an incomplete list of eligible mental functions and the inclusion of adaptive activities, which depend on but are not mental functions, combine to create great difficulty for health providers in completing the Form T2201. The eligibility criteria for mental functions have little clinical relevance.

Many health providers who responded to our survey about the T2201 noted that an application for impairment in mental functions typically generated a clarification letter, which the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) sent to the health provider to request additional information. Health providers told us that they often had no new information and would send back the same responses originally provided.

To tackle these challenges, our Committee spent time identifying the many problems in the current eligibility criteria regarding impairment in mental functions. We also drafted a proposed new definition of mental functions for inclusion in the Income Tax Act. The Committee was pleased that the 2021 federal Budget announced a significant change in the definition of mental functions which, for the most part, was based on our recommendations.

While there are some differences from what we had proposed, we believe that the new list better reflects the components that comprise the mental functions category. The revised criteria will be more relevant to the health providers who complete the Form T2201. The conjunctive requirement that previously applied to mental functions was removed. The new definition of mental functions is discussed in the next section.

The 2021 federal Budget also announced a change in the definition of life-sustaining therapy (LST). It reduces the number of times that a therapy had to be administered from three times a week to twice a week in order to qualify for the DTC. It also allows for the time that secondary caregivers spend in administering life-sustaining therapy. The Committee supports these changes in that they ease the previous eligibility criteria related to LST.

At the same time, we believe it is time for a significant modernization of the definition of life-sustaining therapy. In our view, the eligibility criteria as currently defined are largely unverifiable by health providers.

ii. Administrative improvements

The CRA is bound in its actions by terms and definitions set out in the Income Tax Act, while the Department of Finance Canada is responsible for changes to this legislation. However, the CRA is in a position to introduce administrative reforms that can ease eligibility for various tax measures. We were pleased that the CRA has made several procedural changes that we believe will enable access to the DTC.

One of the most noteworthy actions was the creation of an electronic application Form T2201, a reform that the Committee had proposed. We had noted in our earlier annual reports that an electronic application is consistent with government practice to allow online submission of all kinds of information, applications and payments. It also aligns with the fact that the regular income tax process can now be done completely online.

Perhaps more importantly, the DTC electronic application allows for the provision of a substantial amount of information to both applicants and health providers. Multiple drop-down menus in various places can provide a more detailed explanation of the specific requirements on the Form T2201. The electronic application can include examples of impairment in function, which the Committee has provided, to help health providers interpret the various eligibility provisions.

Yet another advantage to the electronic application is that it enables the tabulation of additional data on the DTC. With a new list of mental functions, for example, it will be easier to collect more detailed information in that area.

Right now, there is no disaggregation of this information. All the applications related to impairment in mental functions are lumped together into one category. It is impossible to know the relative distribution of applicants in the various categories, such as impairment in function related to memory compared to impairment in function linked to emotional regulation. By contrast, there is a detailed breakdown of the categories related to impairment in physical function. We discuss this issue in the section on DTC Data.

Our Committee had also recommended that more assistance be provided to applicants right from the start to ease the complex eligibility process. The CRA introduced a designated call centre with staff trained specifically to respond to DTC-related questions.

In response to another Committee recommendation, the CRA created the new position of Navigator to help applicants with particularly complex cases. There is now a Navigator in each of the three major tax branches throughout the country. Navigators receive referrals from the DTC call centre and assist the referred individuals to work their way through the DTC application process.

All three improvements – the electronic application Form T2201, DTC call centre and Navigator positions – have only recently been introduced. But already, the CRA is reporting a reduction in the number of clarification letters and their associated delays and costs in DTC applications. This is just one barometer of an improved eligibility process. The impact of these new measures must continue to be monitored and assessed over time.

iii. Communication and outreach

Our two previous annual reports had called for improved communications with respect to the DTC and other disability tax measures. We note that the CRA continues to extend its outreach activities and is producing materials in plain language. It is also introducing materials and assistance in various formats to ensure their accessibility to applicants with visual and/or hearing impairments. Our own annual reports were produced as full documents and as one-page organigrams.

However, we recognize that there is still much work to do in terms of ensuring that the CRA web pages and its materials are accessible. We believe that the CRA should carry out regular accessibility audits of its web pages and public materials. All documents and forms should clearly indicate that they are available in alternate formats.

We note in this report the many areas in which improved communication and outreach are required. There is significant work to be done to improve access to disability tax measures by Indigenous peoples. Many are unaware of various tax measures or do not believe they would be eligible to apply.

The Committee was pleased to learn that the CRA recently reorganized its operations by creating a new Disability, Indigenous, and Benefits Outreach Services Directorate. It will reach out specifically to populations that have largely been excluded from tax reductions and tax-delivered income programs.

Other barriers include access to qualified health providers to complete the Form T2201. The Committee has received requests from health provider groups not currently deemed qualified to complete the T2201. These provider groups cited better access as the chief reason why their qualification was necessary. In this third annual report, the Committee recommended that rather than making ad hoc legislative changes as each new provider group seeks eligibility, the CRA should seek one legislative change, entitling any regulated health provider to complete a T2201 in areas consistent with their legislated scope of practice.

Our Committee explored the application of the Jordan’s Principle to the DTC and found that the expense involved in completing the Form T2201, at least for Indigenous children, would be covered by the federal government. Jordan’s Principle was named in memory of Jordan River Anderson. Its purpose is to guarantee that all First Nations children, regardless of their place of residence or condition, have access to the services they require to support their development and meet their needs.

However, more work is required to improve access to disability tax measures and various tax-delivered benefits. Current activities and plans are discussed in the section on Indigenous Issues.

Finally, the Committee has done considerable analysis of DTC data. This analysis provided a picture of trends over time and helped us identify several “red flags” that we highlighted in our previous annual reports. These concerns are discussed in the section on DTC Data.

One notable issue involved the relatively low uptake of the DTC in Quebec. We recently learned that Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) has funded a Quebec-based study to determine why this is the case. Lack of information might be the problem. Alternatively, some potential applicants may believe that they cannot claim both the Quebec disability tax credit and the federal DTC at the same time. Either way, the results of this study will be important for DTC communication and outreach in future.

The disability landscape

Before discussing the Committee’s ongoing work, it is important to highlight several notable changes in the disability landscape that have affected our recent discussions. Perhaps the most significant development was the 2020 federal Throne Speech announcement of a Disability Inclusion Action Plan, which will focus on:

- reducing poverty among persons with disabilities

- getting more persons with disabilities into good quality jobs

- helping to realize the goal of the Accessible Canada Act to achieve a barrier-free Canada

- making it easier for persons with disabilities to access federal programs and services

- fostering a culture of inclusion

The Committee was especially pleased to see reference to the federal government’s plan to introduce a Canada Disability Benefit, which it indicated would be modelled on the Guaranteed Income Supplement for older Canadians. The proposed new benefit could go a long way toward reducing the high rate of poverty among persons with disabilities.

Our Committee had also responded positively to the June 2020 federal announcement of a one-time, tax-free, non-reportable payment recognizing that most persons with severe and prolonged disabilities faced extraordinary pandemic-related costs.

In our second annual report, we noted the limitations in using the DTC as the primary eligibility criterion. Because this tax credit alone proved to be too narrow an eligibility screen, other disability-related programs had to be added to broaden the entry point to the new one-time benefit. The COVID-19 Disability Benefit was eventually paid to all DTC recipients.

This problem proved to be an important lesson in light of the Canada Disability Benefit that the federal government proposed in the Throne Speech. The DTC alone cannot be the sole entry point for this new program. We discuss this issue later in our report.

The Committee notes as well the significance in the disability landscape of the obligations set out in the Accessible Canada Act, which took effect in July 2019. The Act creates a framework to identify, remove and prevent barriers to accessibility and the inclusion of persons with disabilities.

The work of our Committee was also influenced by the fact that Canada is a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). Its purpose is to promote, protect and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by all persons with disabilities and to promote respect for their inherent dignity. Ratification of the Convention obliges signatory state under international law to implement its provisions.

Perhaps most significant from our perspective is the intent of the Convention to move away from a medical model of disability. The DTC, in particular, is a step in this direction because it employs functional capacity as the key eligibility criterion. However, the DTC still requires qualified health providers to attest to the type and degree of functional impairment, which is of course the foundation of the medical model of disability.

The conflict of social and medical models is well illustrated in the DTC. Eligibility criteria are based on function, all or substantially all of the time. While it is applicants and their close contacts who have a first-hand understanding of their function all or substantially all of the time, applications still rely on the judgment of a health provider. The Committee has frequently pointed out that health providers are not with the applicants all or substantially all of the time.

This tension remains unresolved to this day. It will likely continue to present challenges as the federal government contemplates ways to modernize the eligibility process for disability benefits and programs.

Summary

The Committee is pleased that many of our DTC-related recommendations have been implemented. We also note that our concerns regarding longer-term income security improvements are being taken into consideration by the federal government.

Significant work remains, however, with respect to DTC eligibility criteria and administrative procedures, Indigenous issues, DTC data, Registered Disability Savings Plans (RDSPs) and work-related tax measures. We turn now to these areas of ongoing work.

Part 2: DTC Eligibility

Introduction

In this section and throughout our report, the Committee has used the term ‘impairment’ in function because it is consistent with the language in the Income Tax Act and the DTC application Form T2201 (Appendix F). However, we have always been concerned about the impact of language and have tried to encourage the use of terminology that is more consistent with the intent of the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

In both this section and our report, we have retained the term ‘impairment’ for consistency with current legislative and administrative language as well as our earlier recommendations. However, we propose that the term ‘limitation’ be used in all future CRA documents and Committee reports. Moreover, we recommend:

That, in respect of the intent of the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, the Department of Finance Canada and the CRA change the term ‘impairment’ to ‘limitation’ in all of its relevant legislation and administrative procedures and documents.

i. New definition of mental functions

Over the years, it has become clear to the Committee and the disability community, more generally, that most of the eligibility challenges linked to the DTC have arisen around impairment in mental functions. There are problems with respect to how mental functions are defined in the Income Tax Act and how they are assessed on the DTC application Form T2201.

The policy and administrative challenges related to the DTC are not new. They have been documented by many organizations and in various reports for nearly 20 years. Applicants and their families have raised a wide range of concerns, including the complexity of the eligibility criteria. Health providers also told us about the difficulties they face in completing the Form T2201, particularly with respect to impairment in mental functions. Challenges include the fact that the DTC eligibility criteria are not clinically meaningful (e.g. they confuse functions with activities and do not contain a complete list of mental functions) and that the CRA would regularly send requests for additional information to supplement the extensive DTC application already provided.

In 2003, the federal government created the Technical Advisory Committee (TAC) on Tax Measures for Persons with Disabilities. While the TAC made a number of recommendations for reforming the DTC, it identified impairment in mental functions as the most significant eligibility challenge. One of the most important recommendations made by the TAC was a redefinition of mental functions to one that was more accurate, and thereby more fair, when assessing eligibility on the basis of a mental disorder.

The TAC defined mental functions as the range of processes that govern how people think, feel and behave. These processes include “memory, problem solving, judgment, perception, learning, attention, concentration, verbal and non-verbal comprehension and expression, and the regulation of behaviour and emotions.” These processes cover the range of functions upon which we all rely to accomplish the activities of everyday life, such as self-care, health and safety, social skills and simple transactions.

The Income Tax Act was amended in 2005 to modify the definition of mental functions necessary for everyday life. Unfortunately, the amendments at that time were far from what the TAC had recommended and provided little clarity to applicants and to health providers when completing applications for the DTC.

More specifically, the definition of mental functions was modified in the Income Tax Act to read as follows. It remained this way on the application Form T2201 until its recent 2022 update:

- adaptive functioning (for example, abilities related to self-care, health and safety, abilities to initiate and respond to social interactions, and common, simple transactions);

- memory (for example, the ability to remember simple instructions, basic personal information such as name and address, or material of importance and interest); and

- problem-solving, goal-setting, and judgment, taken together (for example, the ability to solve problems, set and keep goals, and make the appropriate decisions and judgments)

It is not clear how the federal government arrived at this redefinition of mental functions. It did not accurately reflect the recommendation on mental functions that the TAC had made. More importantly, the redefinition made no clinical sense for the following reasons:

- It included some but not all mental functions as noted in the redefinition the TAC had proposed

- It required a conjunctive interpretation of problem solving, goal setting and judgment. The requirement not only makes no clinical sense but also discriminates against people with mental disorders since no other category of eligibility (e.g., walking, seeing, speaking) requires a conjunctive presence of multiple symptoms.

- It is a mix of functions and activities. Adaptive functioning is not a mental function. The accomplishment of adaptive activities depends on mental functions. For example, in order to ride a bus or make a purchase in a grocery store, one must be able to attend, learn, make judgments and interact with others.

When the Committee began our work in 2018, one of our first tasks was to identify the many concerns regarding the 2005 revision to the mental functions definition in the Income Tax Act. We reviewed the proposals of the earlier Technical Advisory Committee which, in our view, were still sound.

In 2018, the Committee also carried out an extensive pan-Canadian survey of health providers and received more than 1,100 responses. While the respondents represented several different health professions, psychologists and physicians described the challenges they faced in trying to interpret the impairment in mental functions provisions.

Survey respondents made clear that the eligibility criteria for this functional area are neither clinically meaningful nor easy to understand. The large volume of clarification letters sent by the CRA to health providers completing the application on behalf of persons with impairment in mental functions confirmed the many challenges with the current definition.

The first recommendation in our first annual report proposed that the principle of parity guide CRA actions with respect to physical and mental functions. By this, we meant that the treatment of persons with impairment in mental functions should be the same as those with impairment in physical functions. There should be no additional barrier or higher eligibility bar for applicants with impairment in mental functions.

By requiring a conjunctive presence of impairment in multiple mental functions, an inequity has been created and perpetuated. As noted, no other category of eligibility (e.g., walking, seeing speaking) involves a conjunctive presence of multiple impairments.

Requiring problem solving, goal setting and judgment to all be impaired for a person with a mental disorder to qualify for the DTC is like requiring a person’s nerves, muscles and bones all be impaired for a person who cannot walk. Just as a person with nervous system impairment alone is eligible for the DTC if they cannot walk, a person whose judgment alone is so impaired that they cannot engage in the adaptive activities of everyday life should also be eligible for the DTC.

To address these issues, the Committee searched various international classifications of mental functions to ensure that our proposed new definition would be consistent with clinically recognized and respected taxonomies. Our reformulation of the definition of mental functions derives from international classifications from both the World Health Organization and the U.S.-based National Institute of Mental Health. As noted, we also considered the data from the health providers we surveyed who reported their challenges with Form T2201.

Our goal was to ensure that a revised list of mental functions would make clinical sense, be more clear to applicants and health providers, and be more easily interpreted by the CRA. In Recommendation #2 of our earlier annual reports, we proposed:

That the CRA amend the list of mental functions on Form T2201 as follows:

- attention

- concentration

- memory

- judgment

- perception of reality

- problem solving

- goal setting

- regulation of behaviour and emotions (for example, mood disturbance or behavioural disorder);

- verbal and non-verbal comprehension

- learning.

The Committee took this recommendation even one step further by providing a definition of marked restriction in mental functions. Our Recommendation #7 proposed:

The individual is considered markedly restricted in mental functions if, even with appropriate therapy, medication and devices (for example, memory and adaptive aids):

- all or substantially all the time, one of the following mental functions is impaired, meaning that there is an absence of a particular function or that the function takes an inordinate amount of time:

- attention

- concentration

- memory

- judgment

- perception of reality

- problem solving

- goal setting

- regulation of behaviour and emotions (for example, mood disturbance or behavioural disorder);

- verbal and non-verbal comprehension; or

- learning

Or

- they have an impairment in two or more of the functions listed above none of which would be considered a marked restriction all or substantially all the time individually but which, when taken together, create a marked restriction in mental functions all or substantially all the time;

Or

- they have one or more impairments in mental functions which are: intermittent; and/or unpredictable; and when present, constitute a marked restriction all or substantially all the time.

The Committee was pleased to see that the federal government announced in the 2021 Budget its intent to revise the definition of mental functions in the Income Tax Act. The announcement was a recognition of the many problems in the definition of impairment in mental functions upon which eligibility for the DTC relies. While the proposed change was consistent with our Recommendation #2, it also differed somewhat from our proposal.

In its 2021 Budget, the federal government proposed the following list for its new definition of mental functions:

- attention

- concentration

- memory

- judgement

- perception of reality

- problem solving

- goal setting

- regulation of behaviour and emotions

- verbal and non-verbal comprehension

- adaptive functioning

The Committee was generally supportive of this proposal, which we conveyed in a written submission to the Department of Finance Canada. On the plus side, the federal proposal allows for the disjunctive, rather than conjunctive impairment in problem solving, goal setting and judgment. As noted, there is no conjunctive requirement for any of the identified physical functions. The removal of this requirement is an important step toward parity in the treatment of physical and mental functions.

We were also pleased that the federal proposal largely reflects the list of mental functions that our Committee had presented. We believe that the new list more closely reflects actual mental functions, all of which affect the ability to carry out the activities of daily living. We are concerned, however, about two of the changes that the federal government proposed regarding mental functions.

First, the new definition removed “learning” as a mental function, which was the final entry on our proposed list. We had included “learning” on the list of mental functions for an important reason. We had heard from many health providers, through both focus groups and our health provider survey, who believed that applicants with a severe learning disability would not be eligible for the DTC.

This perception that people with learning disorders are categorically ineligible is not accurate. There is no condition or impairment in function that is categorically excluded from DTC eligibility. While it may be true that learning depends on functions already on the list (e.g., attention, concentration, problem solving), it is also true that applicants and health providers appear to believe that no one with a learning disability would be eligible for the DTC.

It will be important to make clear, in DTC communications and through examples on the Form T2201, that someone with a learning disability may be eligible for the DTC if the learning disability prevented them from engaging in the adaptive activities in everyday life. This might be the case, for example, if a person’s learning disability was so profound that they couldn’t follow directions, make a bank deposit or make a store purchase.

The Committee concluded that omitting learning from the new list of mental functions is not necessarily a problem since learning depends on the ability to attend, concentrate, remember and solve problems – all of which are on the list of functions. As noted, it would be important for the CRA to make clear by example and communication that someone with a learning disability is not necessarily categorically ineligible for the DTC.

The federal government made a second change to the Committee’s proposed list of mental functions. It included “adaptive functioning.” We were concerned to see this addition because the confusion that has long existed among health providers when completing the T2201 is in large measure because the eligibility criteria treats activities as functions.

As mentioned above and in our two previous annual reports, adaptive activity itself is not a mental function. Rather, adaptive activities depend on mental functions. In our view, including adaptive functioning does nothing to make the proposed new list more clear and clinically relevant. In fact, it may perpetuate confusion for health providers who complete the T2201 on behalf of applicants with impairment in mental functions.

In the call by the Department of Finance Canada for public feedback on the proposed legislative change, we pointed out these weaknesses in the hope that these areas could be addressed prior to being introduced into law. We came to understand that adaptive functioning was included out of concern that its exclusion might leave out some applicants who had previously qualified because their ability to carry out adaptive functions was impaired.

We believe that a few factors can mitigate this concern. A critical component of eligibility is that the mental function is so impaired that it prevents adaptive activity all or substantially all of the time. This can be made clear in the form with the use of examples about how disorders in function lead to impaired adaptive activity. It would not be possible to have an impairment in adaptative activities without a disorder of function – following directions, making change in a store, undertaking basic social transactions all depend on mental functions.

Further, to be eligible under mental functions, the adaptative activities that the applicant is unable to perform are very basic ones. A person’s memory must be so impaired, for example, that they cannot make a transaction in a store or follow directions. One will not be deemed eligible for the DTC if one’s memory impairment gets in the way of learning to do complex activities like performing calculus or playing bridge. Just as is the case for learning, we believe that communications and examples of mental functions must make clear that impairments must be severe enough to get in the way of very basic adaptive activities.

Despite the concerns noted above, we supported the proposed changes to the list of mental functions because they are a preferable alternative to the current definition in the Income Tax Act. In our submission to the Department of Finance Canada, we also pointed out other areas of concern. The federal proposal made no reference to the other components with respect to marked restriction in mental functions that we had recommended. These are:

Or

- they have an impairment in two or more of the functions listed above none of which would be considered a marked restriction all or substantially all the time individually but which, when taken together, create a marked restriction in mental functions all or substantially all the time;

Or

- they have one or more impairments in mental functions which are: intermittent; and/or

unpredictable; and when present, constitute a marked restriction all or substantially all the time.

The Committee believes it is essential to make clear that severe and prolonged restriction can be created by impairment in two or more mental functions, when none of the functions creates severe and prolonged impairment on its own.

In addition, the often unpredictable and episodic or intermittent nature of the symptoms of some mental disorders creates severe and prolonged impairment. This fact should be acknowledged in the eligibility criteria.

Our Committee will continue to advocate for these changes. We believe that they are critical in recognizing the potentially profound impact of impairment in mental functions.

We appreciate that, at the time of this writing, the implementation of the proposed legislative changes to the DTC were underway. As of June 23, 2022, the criteria for mental functions and life-sustaining therapy were expanded as detailed above. We respect the intent that these measures would create a fairer and clearer application process and result in more families and people living with disabilities qualifying for the DTC. As mentioned, these changes were very positive but fell short of our recommendations.

It is clear that the changes implemented in June 2022 were informed by our recommendations. The Committee’s understanding of the experiences of relevant stakeholder groups (e.g. health providers, persons with lived experience of disability) can help ensure that legislative changes meet their intended objectives.

Consultation before any future proposals are finalized will help ensure an accurate understanding and interpretation of our recommendations. Fairness for applicants, clarity for health providers and efficiency in the administration of the DTC will more likely be achieved if this consultation is considered.

ii. Interpretation of the new definition

The Committee hopes that the CRA will introduce appropriate administrative solutions to clarify the interpretation of the revised definition of mental functions. The Form T2201 can provide valuable guidance to health providers.

To enable the interpretation of the new definition of mental functions, the Committee suggested that various examples be developed to explain how each of the identified mental functions on the list can be interpreted. In Recommendation #8 of our first two annual reports, we proposed:

That the CRA remove specific references to activities in the T2201 section on mental functions and include examples of activities in the current Guide RC4064 to help health providers detail all the effects of the markedly restricted mental function(s), as in the following illustration:

“The individual is considered markedly restricted in mental functions if they have an impairment in one or more of the functions all or substantially all of the time or takes an inordinate amount of time to perform the functions, even with appropriate therapy, medication, and devices. The effects of the marked restriction in mental function(s) can include, but are not limited to, the following (this list is illustrative and not exhaustive):

- with impaired memory function, the individual cannot remember basic information or instructions such as address and phone number or recall material of importance and interest;

- with impaired perception, the individual cannot accurately interpret or react to their environment;

- with impaired learning or problem solving, the individual cannot follow directions to get from one place to another or cannot manage basic transactions like making change or getting money from a bank;

- with impaired comprehension, the individual cannot understand or follow simple requests;

- with impaired concentration, the individual cannot accomplish a range of activities necessary to living independently like paying bills or preparing meals;

- with impaired ability to regulate mood (for example, depression, anxiety) or behaviour, the individual cannot avoid the risk of harm to self and others or cannot initiate and respond to basic social interactions necessary to carrying out basic activities of everyday life; or

- with impaired judgment, the individual cannot live independently without support or supervision from others or take medication as prescribed.

These examples make clear that the impairments in mental functions must be severe and significant enough that they impact the adaptive activities of everyday life, such as remembering a phone number, following directions and assessing the risk of harm. It would also be helpful for the CRA to conduct surveys or organize focus groups involving health providers to determine whether ongoing improvements to the paper format and electronic applications are required. Respondents may contribute additional examples or helpful clarifications.

The Committee recognizes the need to keep the written Form T2201 to a reasonable length. Fortunately, the electronic application makes it easier to modify various examples or to include new ones.

We were pleased to learn that early feedback from health providers on the electronic application has been positive. We suggest that the CRA continue to update the Committee on a regular basis regarding the content and implementation of the electronic form.

iii. Consistency across impairments

We noted in our first two annual reports the inconsistency in the physical and mental functions set out in the Income Tax Act and Form T2201. Some of the impairments listed as grounds for DTC qualification are functions. They include vision, speaking, hearing, eliminating and eating.

Other categories, notably walking and dressing, represent impairments in activities. Mental functions, as noted, combine an incomplete list of functions (memory, problem solving, goal setting and judgment) as well as activities (adaptive functions).

There is a need for consistency across impairments that grant eligibility for the DTC. It is essential to make a clear distinction between a function or series of functions that are necessary for an activity.

Some activities may be affected because of one or several impairments – e.g., an individual cannot dress because of visual spatial impairment or cannot walk because of upper extremity impairment, fatigue and/or lower extremity impairment.

In fact, the Committee proposed in Recommendation #10 in our first two reports that the CRA revise the list of functions on Form T2201 as follows:

- vision

- speaking

- hearing

- lower-extremity function (for example, walking)

- upper-extremity function (for example, arm and hand movement)

- eliminating

- eating/feeding

- mental functions

The Committee acknowledges that this proposed list would require an update to the Income Tax Act. Because the Form T2201 must reflect the wording of the Act, the CRA cannot introduce this change on its own. But it certainly is an area worth discussing with the Department of Finance Canada.

In Recommendation #11, we made an associated proposal regarding the preparation of a list of activities associated with each impaired function. More specifically, the Committee suggested:

That the CRA create a list of examples of activities for each impaired function for inclusion in Guide RC4064 to help health providers detail all the effects of markedly restricted function(s), as in the following proposed guidelines (this list is illustrative and not exhaustive):

- with impaired lower-extremity function, the individual cannot walk

- with impaired upper-extremity function, the individual cannot feed or dress themselves, or cannot attend to basic personal hygiene

- with impaired eating/feeding, the individual cannot swallow or eat food

Once again, it is possible that some of these areas can be clarified with examples in the drop-down menus of the electronic DTC application. While legislative change is clearly desirable, it is still feasible for the CRA to address the intent of this recommendation through administrative improvements that help achieve its purpose.

iv. The 90% guideline

In order to qualify for the DTC, the mere presence of impairment is not sufficient. Rather, the effect of the impairment upon the basic activities of daily living must be severe and prolonged. In fact, the restriction must be present all or substantially all the time, which has been interpreted by the CRA to generally mean at least 90% of the time.

During the first year of our mandate, discussions around this recommendation were held with Department of Finance Canada officials who raised two issues. First, they argued that a numeric standard provides a more rigorous guideline for decision-making than a set of qualitative benchmarks alone. Second, they noted the policy precedent for this percentage. The 90% guideline is employed in several other contexts, including business and charitable accounts.

Our first annual report documented the many problems with this guideline when applied to the DTC. This requirement acts as a major barrier to DTC eligibility, particularly for persons with impairment in mental functions or other physical conditions (e.g. Multiple Sclerosis) which have many symptoms, some or all of which may be episodic. Symptoms which may be present only 50% of the time, can be as debilitating to the performance of adaptive activities as other symptoms that may be present all of the time.

Take, for example, an individual whose memory or perception of reality is impaired 50% of the time. That person is likely seriously and significantly impaired, and undoubtedly would require a combination of supports, remedial treatments and devices, or medication. Add to that list the fact that intermittent or episodic symptoms are often unpredictable. It is easy to see that if one has a mental or cognitive disorder that results in severe but unpredictable impairment in memory or judgment even 50% of the time, successfully finding the way home from an errand or managing a transaction online or in the store could be at significant risk.

The Committee has also pointed out in the past that there is no basis in law for the 90% guideline. In fact, several judgments in Tax Court cases involving impairment in mental functions have challenged the use of the 90% guideline. It is an administrative practice that is employed to provide a guideline to practitioners and assessors of DTC applications.

In Recommendation #6 of our first and second annual reports, the Committee proposed:

That the CRA no longer interpret all or substantially all as 90% of the time and no longer interpret an inordinate amount of time as three times the amount of time it takes a person without the impairment.

We were pleased to learn that the CRA has agreed to exclude explicit reference to 90% in the DTC electronic application. In addition, DTC assessors now have access to the guidelines in the document Mental functions necessary for everyday life. The guidelines permit more flexibility in the interpretation of “all or substantially all of the time” by noting that the effects of the impairment must be present and challenging “most of the time” rather than the arbitrary 90% rule.

v. Automatic eligibility

While the question of whether certain conditions can create automatic eligibility for the DTC is not new, it remains a challenge. There is no doubt that the presence of certain conditions will likely be associated with higher disability-related costs. In our first two annual reports, we recognized this reality in Recommendation #15:

That the CRA:

- consider whether some conditions, such as a complete paraplegia or tetraplegia, schizophrenia or a permanent cognitive disorder with a MOCA below 16, should automatically qualify for the DTC in the way that blindness does. (MOCA is a mental status examination of cognitive functions used commonly to assess impairment that results from conditions such as dementia, brain injury or stroke); and

- examine the eligibility criteria employed in other federal and provincial/territorial programs, such as the Ontario Disability Support Program and the programs for Canada Pension Plan disability benefits and veterans’ disability pensions to identify the conditions/diagnoses that establish automatic eligibility for those programs

The purpose of this recommendation was to enable access to the DTC. The Committee noted that while diagnosis alone should not necessarily qualify someone for the DTC, the presence of a particular condition may help CRA assessors make their eligibility determinations. Certain conditions, such as paraplegia or dementia, have a predictably stable impact upon daily functioning. Moreover, there is precedence for automatic eligibility – applicants who are blind automatically qualify for the DTC.

At the same time, we acknowledged the problems embedded in this approach. A specific diagnosis does not necessarily result in – or equate with – serious impairment in activity.

We also acknowledged that designated lists in any area of public policy invariably raise questions of fairness about the groups, items or conditions that were left out.

In addition, social models of disability encourage us to consider not just the impairment but the way in which society accommodates impairment. For example, someone who is paraplegic with a fitted wheelchair, transportation, and a community that supports wheelchair use will have less difficulty in accomplishing the activities of everyday life than somebody who does not have access to these resources. After all, the DTC is a tax measure intended to help people reduce their costs because, to some significant degree, society does not accommodate them.

This is clearly a complex recommendation that will need to be revisited in future. It will no doubt come up as an issue as the federal government works to update its procedures involved in disability determination, which we noted in the first section of this report.

vi. Qualified health providers

Throughout our mandate, the Committee has heard from various organizations seeking to expand the list of health providers approved to complete the Form T2201. There were several factors that prevented us from making a recommendation one way or the other about adding other health providers to the list:

- To the best of our knowledge, there are no criteria in place with which the government decides on the inclusion of specific health provider groups and not others.

- We felt that neither our Committee nor the CRA had the authority to expand the list of health providers. Since they are listed in the Income Tax Act, we assumed that the Department of Finance Canada had this authority.

- It is our view that even with the authority, neither the CRA nor the Department of Finance Canada has the expertise to decide which health providers have or do not have the licensed skill sets necessary to support an application for the DTC.

- We felt that we did not have sufficient information about the nature and extent of the difficulty in accessing health providers to complete the T2201 that some had suggested. Several professional groups lobbying to expand the list of health providers had cited the access problem.

The Committee suggested that the CRA include a question in its Client Experience Survey and any other relevant communications, asking about access challenges with respect to the designated health providers identified on Form T2201. We also had proposed the following action in Recommendation #19:

That the CRA develop a process for expanding the list of health providers with the appropriate expertise who can assess eligibility for the DTC.

This recommendation recognized that the CRA likely would receive requests on an ongoing basis to update and expand the list of health providers who can assess for DTC eligibility. We suggested the development of criteria to guide any expansion of the list in future.

Following our second annual report, the Committee struck a Health Provider Task Group, which came up with additional proposals to address this issue. The Task Group suggested that any regulated health provider be allowed to complete the Form T2201 on behalf of applicants.

As a set of new recommendations, the Committee proposes:

That neither the CRA nor Finance decide which health provider can complete the form for which functions but rather let the licensed scope of practice of a health provider guide which functions they will assess on behalf of the DTC applicant.

That any licensed health provider, whose license is in good standing, be permitted to complete the T2201 for any area of function.

We are making these recommendations for the following reasons:

- Health providers are accountable to their licensed scope of practice and transgressing that scope places their license in jeopardy. For instance, an optometrist’s license would not permit them to assess or treat an individual with impaired elimination. A psychologist’s license would not permit them to assess or diagnose diabetes. Accordingly, it is unlikely that a health provider would attest to an area of function around which they had no expertise. Further, if the CRA queried whether a health provider had the expertise to assess the area of function upon which the T2201 is based, they can ask for justification.

- The current assignment of health providers to areas of function is not entirely accurate. An impairment in dressing, for example, may be due to a cognitive impairment (e.g., impaired visual spatial skills) rather than just a motor problem in moving one’s arms. While psychologists are often the health providers who assess and diagnose visual spatial impairment, only occupational therapists, physicians and nurse practitioners can currently complete the Form T2201 for individuals with dressing impairments.

- Allowing the licensed provider to complete the Form T2201 guided by their licensed scope is simpler for the government. It would no longer need to set criteria or make decisions about expanding the list of eligible health providers. The purpose of regulating health professions is public protection to ensure that health providers have the knowledge and skills necessary to assess and treat health problems, and to make these professionals accountable to their knowledge and skills. If they certified an illness or condition without requisite skill, much more is at risk than is gained by completing a Form T2201.

vii. Life-sustaining therapy

The federal Budget 2021 also included a proposed legislative change to the definition of life-sustaining therapy for the purposes of DTC eligibility.

Right now, applicants may be eligible for the DTC if they require life-sustaining therapy. A medical doctor or nurse practitioner must certify that several conditions are met.

An individual must require this therapy in order to support a vital function. This condition applies even if the therapy has eased the symptoms. Previously, the applicant needed this life-sustaining therapy at least three times a week and for an average of at least 14 hours per week. The adoption of proposed changes in Budget 2021 reduces this requirement from three to two times a week.

Over the course of our mandate, the Committee heard several concerns about the eligibility criteria for life-sustaining therapy. These concerns are documented in our first annual report. Perhaps most important, there were questions about the empirical basis for the 14-hour minimum weekly time requirement.

The 14-hour rule includes only the time related to the actual therapy. The requirement assumes that people must take time away from their normal everyday activities in order to receive the therapy. The time may also be spent administering life-sustaining therapy to a child.

In reviewing the eligibility criteria, the Committee has always believed that the requested information on the Form T2201 was too intrusive and likely unnecessary. By definition, a life-sustaining therapy must be frequently administered.

We also wanted to modernize the definition of life-sustaining therapy. Instead of asking health providers for details that they may or may not have, we thought it would be more appropriate to grant DTC eligibility according to the type of therapy required. In fact, very few therapies actually would qualify under the revised definition that we had proposed in Recommendation #14 of our first two annual reports (which we have modified slightly for the purposes of this report):

That the CRA replace the current eligibility criteria for life-sustaining therapies as set out in Form T2201 with the following:

Individuals who require life-sustaining therapies (LSTs) are eligible for the DTC because of the time required to administer these therapies. These are therapies that are life-long and continuous, requiring close medical supervision. Without them, the individual could not survive or would face serious life-threatening challenges. Close medical supervision is defined as monitoring or visits, at least several times annually, with a health provider. These therapies include but are not necessarily limited to: intensive insulin therapy for type 1 diabetes; chest therapy for cystic fibrosis; renal dialysis or chronic and permanent renal failure; intravenous feeding for certain genetic conditions and Crohn’s Disease; and foods for metabolic conditions that prevent the safe breakdown of proteins by the liver, including medically prescribed formulas and foods for phenylketonuria (PKU) and Maple Syrup Urine Disorder (MSUD).

The DAC recommendation basically proposes that any condition which requires life-sustaining therapy, as clearly defined in the above recommendation, should be eligible for the DTC. In our view, the calculation of frequency and time spent are often not readily verifiable by a health provider and should not be required.

The legislative amendment proposed in the federal Budget 2021 basically kept the current LST definition in place. It slightly altered the existing definition by reducing the LST administration from three times to twice weekly.

The amendment also spells out the activities that may or may not be counted in the calculation of the 14-hour rule. These activities include, for example, determination of the dosage of medication; consumption of medical food, formula or compound; and supervision of children or those unable to attend to LST without supervision.

In addition, due to the legislative amendments, an individual diagnosed with type 1 diabetes is now deemed to have met the 2 times and 14 hours a week requirements for life-sustaining therapy. The updated criteria will make it easier for individuals to be assessed and give more eligible people access to the DTC and other benefits.

Committee members would have preferred that the legislative change introduce a more significant reform than the one actually proposed. Nonetheless, we expressed our support for the new measure in that it is a step – albeit a modest one – toward simplifying the DTC eligibility provisions.

Part 3: Ongoing Committee Work

DTC review and appeals

i. Mental functions

The Committee has always been concerned about the eligibility challenges faced by applicants with impairment in mental functions. They face barriers to access and their applications are often denied by the CRA or are sent back to health providers with a request for clarification. Many health providers have informed us that the additional information they submit to the CRA is often identical to or only slightly different from the original application.

In order to reduce the number of cases that go to review, the Committee had proposed the following process in Recommendation #24 in our first and second annual reports:

That in the case of determining DTC eligibility for persons with impairment in mental functions, the CRA include relevant specialized health providers, including, but not limited to, psychiatrists and psychologists, in the review process when applications are disallowed.

In response to this recommendation, the CRA made a commitment to provide better and more consistent training to current and new assessors of DTC cases that involve an impairment in mental functions, and to consult with mental health professionals around selected cases.

All applications denied the DTC involving impairment in mental functions are sent for secondary review by a CRA team not involved in the initial decision.

DTC assessors as well as DTC Objections Centres of Expertise also have access to the guidelines in the document “Mental Functions necessary for everyday life.” The guidelines permit greater flexibility in the interpretation of “all or substantially all of the time” by noting that the effects of the impairment must be present and challenging “most of the time” rather than the arbitrary 90% rule. As noted in an earlier section, the Committee proposed in Recommendation #6 of our first and second annual reports:

That the CRA no longer interpret all or substantially all as 90% of the time and no longer interpret an inordinate amount of time as three times the amount of time it takes a person without the impairment.

The Committee can also monitor progress in this area by continuing to review the DTC data and the approvals with respect to the various functional categories. We can flag concerns related to a drop in approvals related to mental functions.

ii. Improved procedures

The Committee’s earlier annual reports described a range of concerns regarding the DTC assessment process and associated eligibility decisions. We put forward several recommendations to simplify the review process and to make it easier for Canadians to understand and access its various components.

Applicants have the right to challenge decisions with respect to their claim for the DTC. The Appeals Branch has developed an income tax decision tree to explain the process if DTC applicants choose to object to a CRA determination. The decision tree guides them through a series of steps based on their personal circumstances. It is available here: Income tax objections decision tree - Canada.ca.

The Committee had argued that greater awareness of the review process for DTC decisions would help resolve cases at an earlier stage and reduce the need for DTC applicants to challenge decisions regarding their case. We also proposed in Recommendation #23 a broader review:

That the Minister of National Revenue review the current appeals process with a view to creating a straightforward, transparent and informed process where the applicant has access to all relevant information (including the precise reason their application was denied) and documents (including copies of all information submitted by health providers that pertain to their application).

Briefly, there are three main routes to challenge DTC decisions: case review, Notice of Objection and Notice of Appeal. We described these steps in more detail in our second annual report.

For a case review, applicants who receive a Notice of Determination disallowing the DTC are advised that they can request a review of their case. Applicants are required to provide additional relevant medical information that had not already been included with the Form T2201 and clarification letter.

Applicants may also choose to formally object to the initial decision by filing a Notice of Objection, Form T400A, with the Appeals Branch of the CRA (a letter is also acceptable).

Applicants may file an objection regarding a DTC Notice of Determination if they think that the CRA misinterpreted the facts of their circumstances or applied the tax law incorrectly.

The CRA has prepared a video on the objections process, which explains how to file an objection or formal dispute about a DTC determination. It is available here: File an objection – Income tax - Canada.ca.

A second video explains what happens when an applicant registers a formal dispute or objection. It is available here: Processing times and complexity levels - Income tax and GST/HST objections - Canada.ca.

The third step in challenging a DTC determination involves appealing to the Tax Court of Canada. Under what is known as the “Informal Procedure,” the applicant can file a Notice of Appeal (at no fee) within 90 days of the date of the Notice of Confirmation outlining the relevant facts and reasons for the appeal.

The CRA Appeals Branch has prepared a video on how applicants can appeal to the Tax Court if they disagree with the CRA regarding their DTC determination. It is available here: File an appeal to the Court - Canada.ca.

While the Tax Court ensures fairness within the legislative and parliamentary intent of the Income Tax Act, the formal legal route is never the most desirable option in any dispute.

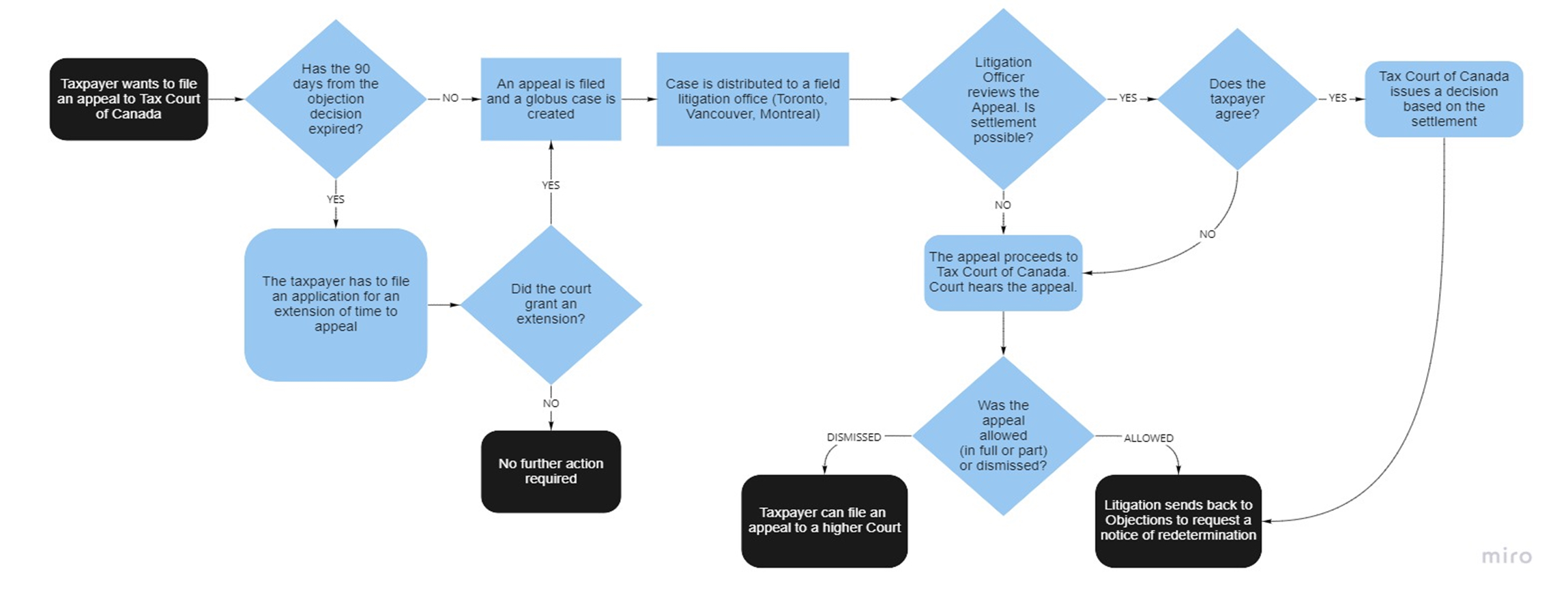

Even with these visual aids and explanations, the process remains intimidating and complex. The Committee struck a Review and Appeals Task Group to continue the discussion related to our ongoing concerns. The Task Group proposed that the CRA provide more detailed information about the various steps involved in questioning a DTC decision. The CRA prepared the following flowchart.

Taxpayer appeals the decision on an objection filed with the CRA

The Task Group also suggested that, in addition to DTC caseload numbers, it would be important to track data on the number of objections and appeals received, approved and rejected. The CRA has informed the Committee that these numbers are, in fact, being tracked by both the appeals Branch and by Navigators. In light of this information, the Committee recommends:

That the CRA shares the data it currently collects on the number of objections and appeals, their nature and the time taken to resolve them in order to determine which groups are experiencing challenges in this regard.

Because of the important gateway role of the DTC, the Task Group wanted to ensure that DTC beneficiaries who are denied eligibility upon request for renewal and then launch an objection or appeal continue to remain eligible for gateway benefits, such as the RDSP and Child Disability Benefit, until the appeal is resolved. The CRA has provided assurance that these gateway benefits are indeed protected. In respect of this fact, the Committee recommends:

That the CRA make clear in its communications that DTC applicants who file an objection or appeal remain eligible for all DTC-related gateway benefits until such time as the objection or appeal is resolved.

Finally, the Task Group undertook an initial review of the language used in the CRA Notice of Determination letters. The review found repeated use of the 90% interpretation of “all or substantially all of the time,” despite the fact that the Committee has been calling for an end to this interpretation.

In our earlier annual reports, the Committee had also expressed concern about the standard being used to determine “hearing” limitations. The Notice of Determination letters use “in a quiet setting” as part of the test. Task Group members questioned whether this requirement recognizes the reality of people’s work lives or their ability to function in a variety of settings.

Under mental functions, the Notice of Determination letter states: “For this credit, difficulties in areas such as working, housekeeping, recreational activities, academic skills (e.g., in mathematics or languages) managing a bank account, and/or driving a vehicle are not considered.” This language does not appear to acknowledge that limitations are increased by barriers within the community. Disability should not be defined simply by an individual’s limitations but also by the barriers that prevent their full participation and citizenship.

The sample language also includes: “Eligibility for the disability tax credit is based on the effects of impairment not on the condition itself.” In relation to mental functions, the Committee has raised questions as to whether a combination of diagnosis and functional limitations or impairments might be used. Mental health conditions are not necessarily a static condition but can fluctuate over time.

Another sample phrase states that: “Children who are not eligible for the disability tax credit are also not eligible for the child disability benefit.” Notice of Determination letters should include the other benefits for which applicants who are refused the DTC may be ineligible.

The Task Group proposed that the following statement be inserted at the head of the Notice of Determination letter: “Information in this letter will be provided in alternative format upon request.” The letter might also provide information about the role of Navigators and their ability to assist with the appeals process.

The Task Group inquired as to whether the CRA website, publications, communications and forms have undergone an accessibility audit. All forms should clearly state that they will be provided in alternate format upon request. They all need to run through language, design and cultural sensitivity toolkits/screening. Appendix G provides a list of resources on language and disability to enable this process.

It was suggested that the CRA hire a student from the Ontario College of Art and Design (OCAD) University’s inclusive design master’s program to review sample communications and potentially create a style guide. The CRA should consider a training module on person-first language for anyone responsible for communicating with the public.

The Task Group also proposed a review of wording of CRA communications to address any issues of cultural sensitivity. Our Committee learned, for example, that there is no word for disability in Indigenous languages. Other Indigenous Issues are discussed in the next section of this report.

iii. Promoters Restrictions Regulations

The complexities involved in applying for the DTC have forced many persons with disabilities to seek assistance from tax promoters and others who charge a contingency fee for their services as well as a percentage of the DTC claim if the application is successful.

In our previous annual reports, the Committee acknowledged that many legitimate tax promoters put in substantial time and effort to assist DTC applicants. At the same time, we wanted to ensure that tax promoters were not charging inordinately high fees for their services. Our Committee had recommended that a cap be placed on these services related to an initial application.

The CRA subsequently drafted regulations that would have capped the promoters fee at $100 for the entire DTC process, including any appeals. However, an injunction launched by a BC-based promoters’ group was granted by the Supreme Court of British Columbia. The legal action halted the imposition of the $100 fixed-fee schedule that was due to take effect November 15, 2021.

In response to the BC Court injunction, the CRA reviewed and amended an administrative policy related to the Disability Tax Credit Promoters Restrictions Regulations (the Regulations). The CRA’s interpretation of the term “disability tax credit request,” for the purposes of the Regulations, no longer includes the filing of a Notice of Objection. This means the maximum fee of $100 will not apply to work done to assist with the filing of Notices of Objection.

DTC Legal Issues

Several legal issues related to the DTC were brought to the attention of the Committee. These pertain to legal representation and the Trust and Principal Residence Exemption.

i. CRA legal representative

If a person with a mental disability is found at any time to be incapable of managing their financial affairs, the CRA requires that another person be named as the legal representative to manage tax matters on that person’s behalf. The definition of legal representative is spelled out in the Income Tax Act (see Appendix H).

The CRA specifies that a legal representative includes “someone with a power of attorney, someone named in a representation agreement or a guardian.” This means that a person with an impairment in cognitive mental function, in particular, must be represented by a legal guardian if they are deemed incapable of managing property or appointing someone as an authorized representative.

In provinces or territories without supported decision-making legislation, a DTC applicant may not meet the legal threshold to grant a power of attorney for property. In this case, a trusted family member would have to be appointed, for CRA purposes, as the person’s legal guardian.

This requirement gives rise several problems. Applying for legal guardianship is often a complicated process, involving capacity assessment of the person with a disability, application with the court, and significant time and cost commitment. Moreover, the appointment of a legal guardian removes the ability of the individual to make decisions regarding their property.

The lack of supported decision-making options in the Income Tax Act contravenes the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, which Canada has ratified. The CRA insistence on the appointment of a legal representative is also inconsistent with social assistance programs across the country, which generally allow for representatives to be named without resorting to legal guardianship.

It is important to note that, in 2004, a CRA Technical Interpretation allowed for “next-of-kin” to qualify as a legal representative of a person with a disability, in accordance with the definition of legal representative in the Income Tax Act.

This Technical Interpretation makes it possible to appoint a representative on an informal basis. It saves cost and time as well as respects personal autonomy. The representative’s involvement in the individual’s personal affairs is limited to tax matters only and their representation can be revoked by the individual at any time. This Technical Interpretation, however, has not been operationalized by the CRA.

The Department of Finance Canada has the authority to amend the Income Tax Act to improve access to CRA-administered measures by persons with impairment in cognitive mental functions. Even in the absence of legislative change, the CRA is able to reform its administrative practices. It can allow these individuals to appoint a representative to support them in managing their tax affairs. British Columbia’s Representation Agreement Act may be an appropriate precedent for CRA to include supported decision-making options for people who currently face barriers to engaging with CRA (see Appendix H).

To resolve the legal representation issue, the Committee recommends:

That the Department of Finance amend the Income Tax Act (ITA) and/or that the CRA amend its policy to allow a person to appoint a representative to support them with respect to the management of their tax affairs. This objective can be achieved by:

- adding “supported decision-maker” to the enumerated legal representatives in the definition of legal representatives in s. 248(1) then adding a new section to the Income Tax Act that sets out the procedure for appointing a supported/supporting decision-maker; or

- revising the policy applying to the appointment of an “authorized representative” such that it applies to people who may not meet the current capacity requirements to carry out this process.