International Health Regulations - Joint External Evaluation of Canada Self-Assessment Report

April 20, 2018

Public Health Agency of Canada

Foreword

The world we live in today is characterised by the movement of information, products and people at unprecedented levels. While these exchanges have innumerable benefits, they also present new types of risks, particularly to health. It is imperative that risks be mitigated and managed by a strong health system with appropriate ties to the authorities responsible for emergency management, borders, and national security.

All 196 States Parties to the International Health Regulations (2005), including Canada, recognize that protecting health security requires all countries to establish public health core capacities to prevent, detect, and respond to significant events with health consequences. Over the last 20 years, infectious disease outbreaks including SARS, H1N1, Ebola in West Africa, and Zika, have amplified the need for a global approach to health security. Canada's own experience and participation in international response to public health emergencies has allowed us to see clearly the extent of the consequences public health emergencies can have on a society, and the pressing need to ensure measures are in place to prevent and mitigate these kinds of events. The Joint External Evaluation will provide Canada with an evidence-based set of recommendations to build national resilience and contribute to international health security.

Municipal, provincial, territorial, and federal levels of government have established innovative programs and capacities to protect the health of their residents and respond quickly to emerging risks. Completing an external review of Canadian core public health capacities is an opportunity to highlight our country's successes, but also to reflect on persisting challenges and imagine new ways of improving our systems.

We are proud to acknowledge the body of evidence gathered here through extensive collaboration with jurisdictional partners in health and other sectors. This report describes Canada's progress on 48 indicators across 19 technical areas. It provides a unique overview of Canada's health system and current state of public health preparedness. Our hope is that it will inspire future research and encourage innovation at local, provincial, regional and national levels.

Siddika Mithani, PhD

President, Public Health Agency of Canada

Dr. Theresa Tam

Chief Public Health Officer of Canada

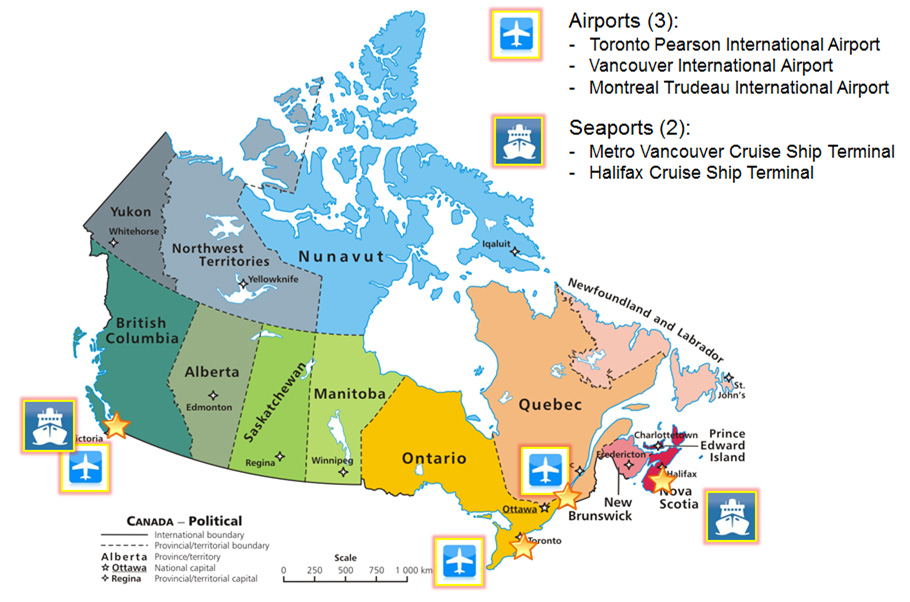

Canada's health System

Canada is the second largest country in the world by total area covering 9.9 million square kilometres. Canada is home to 36.7 million people, more than 80,000 known wildlife species, and almost 200 million livestock. Although it has one of the world's lowest human population densities (4 people per km2), most Canadians (76%) live in urban centres along the border with the United States, with more than a third (36%) of the population living in the country's three largest cities: Toronto, Montreal or Vancouver.

Canada is a constitutional monarchy with multiple levels of government, including federal, provincial or territorial, and indigenous self-governments. Each level of government has its own areas of responsibility, but there are also areas where governments share responsibility. The federal government deals with areas of law listed in the Constitution Act, 1867 and that generally affect the whole country, such as national defence, foreign affairs, and Aboriginal lands and rights. Through "equalization payments" the federal government plays a role in addressing fiscal disparities between provinces and in ensuring that standards of health, education and welfare are the same for every Canadian.

Provincial and territorial governments have the power to make laws that affect their province or territory directly and to manage their own public lands. They are also responsible for health care delivery and education. Municipal governments run cities, towns or districts, including managing community water systems, local public land, and emergency first responders (police, fire protection, ambulances).

Indigenous self-government is part of Canada's evolving system of cooperative federalism and distinct orders of government. First Nations communities in Canada have a separate autonomous governance structure of elected band councils with responsibilities and authorities similar to those of municipal governments and with increasing powers over health in their communities.

Agriculture, immigration and health are some of the areas where the federal government and provinces and territories share responsibility.

Disease in Canada

In general, Canadians experience good health on a number of measures-almost 90% of Canadians report having good to excellent health, 92% say their lives are satisfying or very satisfying, and 70% of Canadians report having very good or excellent mental health. Canada's average life expectancy of 82 years ranks it among the healthiest nations in the world.

Canada has made great advances in preventing and controlling infectious diseases, through widespread improvements in hygiene and sanitation, water treatment systems, food safety measures, mass immunization programs, research into and development of new drugs, and education campaigns around safe sex, handwashing and safe food preparation. Canada also has better surveillance systems in place, providing a clearer picture of immunization rates and the distribution of diseases. Despite these advances, Canadians are still getting sick from infectious diseases and some of this sickness is long-term and treatment resistant, creating situations of vulnerability. In addition, some Canadians are not as healthy as others or are at a higher risk for poor health outcomes. Indigenous and low income households in Canada, for example, still live with higher rates of inadequate housing and food insecurity, compared to other Canadians. As well, Canada's geography, population distribution, and cultural differences create unique challenges to the delivery of health services in the country's northern, remote and rural communities.

While chronic diseases like diabetes, cancer, and cardiovascular disease are the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in Canada, infectious diseases continue to impose a significant burden on populations and health systems. Infectious disease priorities in Canada include, rates of antimicrobial resistance (AMR); vaccine coverage and the re-emergence of childhood vaccine-preventable diseases, such as measles and whooping cough; increasing rates of sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections; vector-borne diseases emerging as a result of climate change, such as Lyme disease; increasing rates of salmonella; and the disproportionately high rates of tuberculosis among foreign-born, First Nations and Inuit populations in Canada.

Although overall Canada's AMR rates are relatively low, there are upward trends in the rate of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) blood stream infection (BSI) in pediatric hospitals; in the rate of vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus (VRE) BSI in adult hospitals; and in the rates of drug-resistant gonorrhea in Canada.

The incidence of vaccine-preventable diseases in Canada is low. However, the viruses and bacteria that cause these diseases circulate within Canada and around the world and can still potentially cause outbreaks in under- and un-immunized groups. Since 2005 Canada has had a number of imported cases of measles resulting in spread and outbreaks within Canada. These importation events underline the ongoing risk of resurgence and the importance of achieving and maintaining Canada's vaccination coverage goals. Canada's public health and surveillance efforts have continued to maintain elimination of endemic measles in Canada. Raising immunization rates for measles, diphtheria, pertussis and tetanus in Canada-which currently are below national coverage goals of 97% by age two years-will further guard against the spread of these diseases following importation by travellers returning from endemic countries.

Government investments have contributed to the prevention and control of some sexually transmitted and blood borne infections. However, new HIV and hepatitis C infections continue to occur among certain populations and reported rates of chlamydia, gonorrhea and syphilis in Canada have been steadily rising since the late 1990s.

Climate change has been implicated in rising rates of vector‐borne communicable diseases in Canada. West Nile Virus appeared in Canada for the first time in 2002 and the incidence of Lyme disease has been increasing as higher temperatures allow mosquitoes and ticks to spread within Canada.

Serious outbreaks of food-borne diseases are rare in Canada. However, food-borne bacteria, parasites and viruses still cause illnesses in Canada. Every year, about 4 million (1 in 8) Canadians are affected by a food-borne illness. Over the last three years salmonella rates in Canada have increased mainly attributed to a rise in the incidence of salmonella enteriditis.

Canada has one of the lowest incidence rates of tuberculosis in the world at 4.4 cases per 100,000 population. Although the overall incidence of tuberculosis in Canada has steadily decreased over the last 30 years, tuberculosis continues to disproportionately affect First Nations and Inuit populations, with incidence rates of 20.4 per 100,000 and 198.3 per 100,000, respectively.

Diseases and conditions linked to unhealthy living (diabetes, obesity and mood disorders) have been increasing in Canada. Over a relatively short period of time, for example, the proportion of Canadians living with diabetes almost doubled from 6% in 2000 to 10% in 2011. This is a concern because type 2 diabetes is linked to higher proportions of people with an unhealthy diet, low physical activity and higher rates of obesity, all of which are linked to a variety of other diseases and conditions, making them proxies for overall health. Moreover, the gap between the highest and lowest income groups is widening. In 2014 Canadians in the lowest income group were twice as likely to report living with cardiovascular disease as those in the highest income group.

As a major exporter of live animals and animal products, and also a significant importer of animal products, and some live animals, Canada adopts a very rigorous approach to identifying and mitigating possible risks and has strict border controls in place. Despite the low levels of accepted risk, Canada has faced a number of major disease challenges in recent years including bovine spongiform encephalopathy, avian influenza and bovine tuberculosis. These outbreaks of foreign animal diseases have been effectively managed and the diseases either eliminated or are in the process of being controlled. Canada has also implemented a number of effective disease control and eradication programmes, including programs against tuberculosis and brucellosis.

Key features of Canada's health care system

Canada's core publicly funded health care system, known as Medicare, provides universal coverage for medically necessary hospital and physician services-patients do not pay user fees. While there are government programs that provide access to non-Medicare services for certain groups, such as children, seniors, and people with low incomes, the majority of working Canadians have private insurance plans to pay for services not covered by Medicare, such as prescription drugs outside of hospitals, vision care, dental care and physiotherapy. Quebec is the only province with a universal prescription drug plan. If neither public nor private insurance covers the full cost of a service, patients must pay out-of-pocket. While the Canadian health care system is mostly publicly funded through taxes, health care services are provided by a mix of public and private organizations and self-employed professionals.

The Canada Health Act sets out the criteria and conditions that provincial and territorial health care insurance plans must meet in order to receive the full federal cash transfer (Canada Health Transfer) to which they are entitled under the act. The five principles enshrined in the act are:

- Public administration: public health care insurance plans must be administered on a non-profit basis by a public authority

- Comprehensive: plans must cover all medically necessary hospital and physician services

- Universal: all eligible residents must be entitled to coverage on uniform terms and conditions.

- Portable: Coverage must be maintained when the insured person travels within Canada or abroad, within prescribed limits.

- Accessible: Reasonable access to insured health services must be maintained and unimpeded by financial or other barriers.

The act also discourages extra-billing and user charges for insured health services through mandatory dollar-for-dollar deductions from federal transfers.

Role of governments

Health care in Canada is primarily a provincial and territorial responsibility. Provinces and territories manage and deliver health care services in their jurisdictions (accounting for about 65% of Canada's total health expenditures). The federal government, through the Canada Health Act and other legislation, also plays an important role in matters that affect the health of Canadians, such as funding, regulating food and drugs, and setting national standards for health care.

Provinces fund and administer health insurance plans and other health care programs and they determine the organization and governance of their own health care systems. They regulate health care facilities and professionals, as well as private insurance; they manage capital investments; and they negotiate purchasing and pricing for their drug plans.

In provinces, regional health authorities plan, fund and deliver (within a defined geographical area) health care services, such as hospital care, rehabilitation and home care. However, regional health authorities are not responsible for physician services and drug plans, which remain the responsibility of provincial and territorial governments.

The planning and delivery of public health services in Canada is mostly done at the local or regional level through health departments of regional health authorities or districts or through health units and municipal health departments. These organizations have their own governance structures and their activities are governed by a provincial or territorial public health act (or equivalent) and its regulations, as well as by specific provincial or territorial legislation, policy, directives and conditions of funding--all of which vary from province to province. There is also considerable variation among public health units, which can serve populations from 600 to 2.4 million people with catchment areas from four to 800,000 square kilometers.

In addition, each province and territory has a chief medical officer of health (or equivalent) whose reporting relationship also varies considerably across the country as each province or territory tries to balance the independence of the CMOH as a health advocate with the need to integrate the portfolio into ministries of Health.

The federal government sets and administers national standards for Canada's health care system and funds provincial and territorial health care services through the Canada Health Transfer, an annual cash transfer to provinces and territories amounting to $37 billion in 2017-18 (about 23% of the total provincial and territorial health care expenditure). The federal government also regulates products, such as food, drugs, and pesticides, as well as medical and radiation-emitting devices; and it delivers or funds health care services to specific groups, including First Nations living on reserve, members of the Canadian Armed Forces, veterans, refugee claimants, and federal inmates. Indigenous Services Canada has a mandate to provide certain public health services to First Nations communities on reserve. Many Indigenous self-government agreements include the responsibility to deliver health care and public health services to their population.

All levels of government share responsibility for health care funding, health research and health promotion and protection, including emergency preparedness and response activities.

Funding

Canada spent about $242 billion on health in 2017. Although the system is predominantly publicly financed (70%), private financing (30%) plays an important role: private health insurance for services not covered by Medicare accounts for about 12% of Canada's health spending, while out-of-pocket payments by individuals for health services accounts for another 15%. Donations and other non-patient revenue streams make up the remaining 3% of private financing.

Besides the Canada Health Transfer to the provinces and territories, the federal government spent about $8 billion in 2017 (3% of total health spending) on direct health expenditures. Revenues for the publicly funded portion of health care expenditures come from federal, provincial and territorial tax revenues.

Health and medical research

Health research advances our understanding of the factors that influence health and plays an important role not only in improving health outcomes for Canadians but also in contributing to Canada's overall social and economic prosperity. Health research in Canada is supported by the federal and provincial governments, non-government organizations and industry. Most health research in Canada is conducted by the higher education sector (in association with research hospitals), industry and non-governmental organizations and some is conducted in the federal government's own facilities.

The Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) is Canada's major federal funder of health research. CIHR invests approximately $1 billion each year to support both investigator-driven (72%) and priority-driven (28%) health research in all four pillars: biomedical, clinical, health systems services, and population health. Chosen through a peer review process that ensures quality and fairness, top investigator-driven research proposals are funded through a variety of programs. Priority-driven research initiatives are created by the Government of Canada to investigate pressing health issues that are of strategic importance to the country.

CIHR's 13 institutes align their individual strategic plans with the overarching direction and goals of Canada's Health Research Roadmap II. Institutes work with stakeholders across disciplines, professions, sectors and geographic borders to identify health and health system needs and capture emerging national and international scientific opportunities.

Other federal funders of health research in Canada include the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council, Health Canada, Canadian Institute for Health Information, Genome Canada and the Canadian Foundation for Innovation.

Provincial research funding agencies also contribute to medical research and training in Canada through organizations such as Alberta Innovates, Fonds de recherche santé du Québec, Manitoba Health Research Council, Newfoundland and Labrador Centre for Applied Health Research, and British Columbia's Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

Self-assessment process

Canada announced at the North American Leaders' Summit in June 2016 its commitment to undergo a Joint External Evaluation (JEE) in June 2018. Project planning got underway in the fall of 2016, about 18 months before the planned site visit of the external evaluation team, and was achieved in four phases:

- Planning

- Stakeholder engagement

- Self-assessment

- External evaluation (site visits)

Led by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), the project involved 10 federal government departments and representatives from 13 provinces and territories.

A small project team was established within PHAC's Centre for Emergency Preparedness and Response. The project team worked with technical experts, policy analysts and senior managers within the Agency to design and hold stakeholder consultations, coordinate the gathering and validation of evidence for all 48 indicators, draft and produce Canada's self-assessment report, and plan and coordinate the external evaluation team site visit. (Table 1: Project Plan for Canada's Joint External Evaluation, June 2016 to June 2018)

The team identified technical leads-experts in each of the various technical areas-from PHAC, Health Canada, and the Canadian Food Inspection Agency to act as liaisons between the project team and program areas, to help gather data for the indicators, and to draft the self-assessment report's 19 technical chapters. Technical leads consulted with other experts within relevant federal program areas and with provincial and territorial colleagues, including a two-day meeting in November 2017 to discuss the evidence and to propose scores for each indicator.

| Phase | Activities |

|---|---|

| 01 Planning November 2016 to March 2017 |

Project team:

|

| 02 Stakeholder engagement January 2017 to March 2017 |

Project team:

|

| 03 Self-Assessment March 2017to December 2017 |

Project team:

Technical leads:

|

| 04 External Evaluation January 2018 to June 2018 |

Project team:

|

Self-assessment results

Indicator scores

Canada's Self-Assessment Report is an aggregate national assessment that was developed in consultation with federal, provincial and territorial governments. The indicator scores presented in table 2 below are the outcome of a two-day consultation with federal, provincial and territorial officials. The evidence in the technical chapters of this report and the proposed scores (on a scale of 1 "no capacity" to 5 "sustainable capacity") have been reviewed, validated and agreed upon by a wide range of government partners and technical experts.

| N/A | Indicator number | Description | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| P1 Legislation | P1.1 | Legislation, laws, regulations, administrative requirements, policies or other government instruments are sufficient for implementation of IHR | 5 |

| P1.2 | The state can demonstrate that it has adjusted and aligned its domestic legislation, policies and administrative arrangements to enable compliance with the IHR | 4 | |

| P2 IHR Collaboration | P2.1 | A functional mechanism is established for coordination and integration of relevant sectors in the implementation of the IHR | 4 |

| P3 Antimicrobial resistance | P3.1 | Antimicrobial resistance detection | 3 |

| P3.2 | Surveillance of infections caused by antimicrobial resistant pathogens | 3 | |

| P3.3 | Healthcare associated infection prevention and control programs | 4 | |

| P3.4 | Antimicrobial stewardship activities | 3 | |

| P4 Zoonoses | P4.1 | Surveillance systems in place for priority zoonotic diseases/pathogens | 4 |

| P4.2 | Veterinary or animal health workforce | 4 | |

| P4.3 | Mechanisms for responding to infectious zoonoses and potential zoonoses are established and functional | 4 | |

| P5 Food safety | P5.1 | Mechanisms are established and functioning for detecting and responding to food borne disease and food contamination | 5 |

| P6 Biosafety and biosecurity | P6.1 | Whole-of-government biosafety and biosecurity system is in place for human, animal, and agriculture facilities | 5 |

| P6.2 | Biosafety and biosecurity training and practices | 4 | |

| P7 Immunization | P7.1 | Vaccine coverage (measles) as part of national program | 3 |

| P7.2 | National vaccine access and delivery | 5 | |

| D1 National laboratory system | D1.1 | Laboratory testing for detection of priority diseases | 5 |

| D1.2 | Specimen referral and transport system | 5 | |

| D1.3 | Effective modern point of care and laboratory based diagnostics | 5 | |

| D1.4 | Laboratory quality system | 4 | |

| D2 Real time surveillance | D2.1 | Indicator and event based surveillance systems | 5 |

| D2.2 | Interoperable, interconnected, electronic real-time reporting system | 4 | |

| D2.3 | Analysis of surveillance data | 5 | |

| D2.4 | Syndromic surveillance systems | 5 | |

| D3 Reporting | D3.1 | System for efficient reporting to WHO, FAO and OIE | 5 |

| D3.2 | Reporting network and protocols in country | 5 | |

| D4 Workforce development | D4.1 | Human resources are available to. Implement IHR core capacity requirements | 5 |

| D4.2 | Applied epidemiology training program in place | 5 | |

| D4.3 | Workforce strategy | 4 | |

| R1 Preparedness | R1.1 | Multi-hazard national public health emergency preparedness and response plan is developed and implemented | 5 |

| R1.2 | Priority public health risks and resources are mapped and utilized | 3 | |

| R2 Emergency response operations | R2.1 | Capacity to activate emergency response operations | 5 |

| R2.2 | Emergency operations centre operating procedures and plans | 5 | |

| R2.3 | Emergency operations program | 4 | |

| R2.4 | Case management procedures are implemented for IHR relevant hazards | 5 | |

| R3 Linking public health and security authorities | R3.1 | Public health and security authorities (law enforcement, border control, customs) are linked during a suspect or confirmed biological event | 4 |

| R4 Medical countermeasures | R4.1 | System is in place for sending and receiving medical countermeasures during a public health emergency | 5 |

| R4.2 | System is in place for sending and receiving health personnel during a public health emergency | 5 | |

| R5 Risk communications | R5.1 | Risk communication systems | 4 |

| R5.2 | Internal and Partner Communication and Coordination | 5 | |

| R5.3 | Public Communication | 4 | |

| R5.4 | Communication engagement with affected communities | 4 | |

| R5.5 | Dynamic listening and rumour management | 3 | |

| Points of entry | POE 1 | Routine capacities are established at points of entry | 5 |

| POE 2 | Effective public health response at points of entry | 5 | |

| Radiation emergencies | RE 1 | Mechanisms are established and functioning for detecting and responding to radiological and nuclear emergencies | 4 |

| RE 2 | Enabling environment is in place for management of Radiation Emergencies | 5 | |

| Chemical events | CE 1 | Mechanisms are established and functioning for detecting and responding to chemical events or emergencies | 4 |

| CE 2 | Enabling environment is in place for management of chemical events | 4 |

P1: National legislation, policy and finance

Joint external evaluation target: States Parties should have an adequate legal framework to support and enable the implementation of all of their obligations and rights to comply with and implement the IHR (2005). In some States Parties, implementation of the IHR (2005) may require new or modified legislation. Even where new or revised legislation may not be specifically required under the State Party's legal system, States may still choose to revise some legislation, regulations or other instruments in order to facilitate their implementation and maintenance in a more efficient, effective or beneficial manner. States Parties should ensure provision of adequate funding for IHR implementation through the national budget or another mechanism.

Level of capability in Canada

Canada implements the International Health Regulations (IHR) under existing legislation, regulations, policies and agreements in place at both the federal, and the provincial and territorial levels. An internal review conducted in 2010 found that the legislative and non-legislative measures taken by federal, provincial and territorial governments were sufficient to support implementation of the IHR in Canada.

As a federated state, Canada requires federal, provincial and territorial cooperation to implement the IHR. Provinces and territories have primary responsibility for health, public health and emergency response in their jurisdictions. Accordingly, they have their own legislation and regulations for governing these activities.

The federal government shares responsibility for public health with provinces and territories and delivers health care to specific populations (First Nations on reserve, Inuit, federal inmates and Canadian Armed Forces personnel). It also has responsibility and authority in sectors that affect public health. Examples of the core federal public health legislation and regulations are:

- Department of Health Act

- Public Health Agency of Canada Act

- Quarantine Act

- Human Pathogens and Toxins Act and Human Pathogens and Toxins Regulations

Federal legislation also governs sectors that affect public health, such as nuclear safety, radiation protection, food safety, and animal health.

National (federal-provincial-territorial) collaborating mechanisms, agreements, policies and plans are in place that clarify roles, help align legal and policy frameworks across jurisdictions, and ensure effective cooperation in emergencies. In particular, the Pan-Canadian Public Health Network plays a unique role in public health in Canada. It provides a national governance structure to support evidence-based decision making, information sharing and dissemination, and coordination and collaboration across jurisdictions. The Network has led to many important national agreements and plans, such as the Multi-lateral Information Sharing Agreement, the Federal, Provincial and Territorial Public Health Response Plan for Biological Events, and the Canadian Pandemic Influenza Plan for the Health Sector.

As well, Canada has a memorandum of understanding on the provision of mutual aid in relation to health resources during an emergency affecting the health of the public. The Operational Framework for Mutual Aid Requests for Health Care Professionals (OFMAR) puts the principles of the MOU into practice. This mutual aid agreement serves as an important means to ensure that all jurisdictions have the resources they need to respond to a public health emergency, including those that may not have the capacity to respond to a complex emergency.

Following the SARS outbreak in 2003, Canada strengthened its federal public health capacity by creating the Public Health Agency of Canada (the Agency) in 2004. Part of Canada's Health Portfolio, the Agency supports the Minister of Health in exercising the powers, functions and duties related to public health, which can be found in legislation such as the Department of Health Act. They can also result from programs approved by Cabinet and funded by Parliament through appropriations submitted for approval by the President of Treasury Board.

The Agency is the IHR National Focal Point for Canada. It facilitates coordination and collaboration of IHR implementation with provinces and territories and across the federal government. As an Agency program, the National Focal Point receives stable funding through the federal government's annual budgeting process. Canadian government organizations at all levels implement the IHR as part of their core mandate.

Canada is also an active participant in cross-border plans, agreements and networks (Global Health Security Initiative, North American Plan for Animal and Pandemic Influenza) that further, enable or strengthen national and international IHR compliance.

Government programs that deliver on IHR requirements are funded through regular annual budgeting processes. The federal government publishes online annual departmental reports on plans and priorities which must show budget allocations to support programs. Governments in Canada also make special funds available quickly to support emergency response activities.

Indicators

P1.1 Legislation, laws, regulations, administrative requirements, policies or other government instruments in place are sufficient for implementation of IHR

Canadian laws and regulations governing public health surveillance and response

Canada has an extensive range of legislation, regulations, policies and other instruments in place for governing public health surveillance, preparedness and response, and to support its compliance with the IHR and its ongoing strengthening of implementation.

Public health in Canada is a responsibility shared among federal, provincial, territorial and local governments. Provinces and territories have their own legislation governing emergency response. They also have public health legislation that establishes authority for public health surveillance and requires local public health staff to report notifiable diseases to public health officials. Provinces and territories, because they are responsible for delivering health services, are important partners and contributors of surveillance information in Canada.

The federal mandate to carry out surveillance is derived from the powers and obligations conferred on the Government of Canada by a number of acts, including the Department of Health Act and the Public Health Agency of Canada Act. The Department of Health Act gives the Minister of Health a broad mandate to protect Canadians against health risks and the spread of disease.

The Minister's duties, functions and powers include investigation and research into public health, including the monitoring of diseases and, subject to the Statistics Act, "the collection, analysis, interpretation and publication and distribution of information relating to public health."

The Public Health Agency of Canada was established to assist federal efforts to identify and reduce public health risk factors and to support national readiness for public health threats, including responding to a public health emergency. The Public Health Agency of Canada Act outlines the measures that the Agency can take in public health, including health surveillance and public health emergency preparedness and response.

The Public Health Agency of Canada Act mandates the Agency, in collaboration with its partners, "to contribute to federal efforts to identify and reduce public health risk factors and to support national readiness for public health threats." The act recognizes that public health surveillance is one of the public health measures that the Government of Canada undertakes through various programs and activities carried out by the Agency.

The Agency is responsible for assisting the Minister of Health in exercising or performing her functions relative to public health. Other departments within the Health Portfolio are Health Canada, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and the Patented Medicine Prices Review Board.

The Department of Health Act and the Public Health Agency of Canada Act do not expressly deal with the collection of personal information. However, under section 4 of the Privacy Act, the Agency can collect personal information for the purpose of carrying out programs and activities to assist the Minister in exercising her powers, duties and functions relative to public health, if the collection relates to that program or activity. Provinces and territories comply with the IHR obligation to disclose information for the purposes of managing a public health risk, in accordance with relevant domestic laws.

Other key federal legislation and regulations that enable Canada to meet its IHR obligations include:

- Quarantine Act: authorizes the measures that can be taken at points of entry or departure to control the spread of diseases that pose a significant risk to public health. This includes measures taken with respect to conveyances and their cargo.

- Potable Water on Board Trains, Vessels, Aircraft and Buses Regulations: governs the safety of water for drinking, hand washing, and preparation of food on certain conveyances.

- Human Pathogens and Toxins Act and Human Pathogens and Toxins Regulations: establishes a safety and security regime to protect the health and safety of the public against risks from human pathogens and toxins. The act takes a risk-based approach-identifying three risk groups-and covers obligations and prohibitions, licensing, standards, guidelines and enforcement.

- Food and Drugs Act and Food and Drug Regulations: establishes standards for the safety and nutritional quality of all foods sold in Canada. The act covers food content, as well as its manufacture, preparation, preservation, packaging and storing. It also authorizes enforcement measures, from inspections to seizures and destruction.

- Emergency Management Act: authorizes the Minister of Public Safety to coordinate emergency management activities with government institutions and in cooperation with the provinces and territories. This includes monitoring potential, imminent and actual emergencies and advising other ministers. The act also directs all federal ministers to identify risks in their area of responsibility and prepare emergency response plans for those risks.

- Health of Animals Act and the Health of Animals Regulations: protect animals and animal health, providing for the control of diseases and toxic substances that may affect land and water animals or that may be transmitted by animals to people. This includes segregation and inspection of animals, the importation of animal by-products, quarantine of imported animals, eradication of diseases, regulation of veterinary biologics, as well as permits and licencing and animal identification.

- Canadian Environmental Protection Act: aims to protect the environment and human health from pollution and toxic substances. The act covers pollution prevention through, among others, regulation of vehicle emissions and timelines for the management of toxic substances.

- Nuclear Safety and Control Act: establishes the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission and authorizes it to regulate the development and use of nuclear energy and the production, possession and use of nuclear substances to limit the associated risks to national security, the health and safety of people and the environment.

- Nuclear Terrorism Act: strengthens authority to respond to nuclear terrorism threats and allows Canada to fulfill international commitments relative to nuclear security.

- Radiation Emitting Devices Act and Radiation Emitting Devices Regulations: authorizes Health Canada to set and enforce standards for the sale and use of these devices, including inspections, testing, and the provision of safety guidance.

- Transportation of Dangerous Goods Act: promotes public safety in the transportation of dangerous goods and covers, among other things, safety and security requirements, emergency response plans, containment and shipping rules and standards, inspection and monitoring, and certification.

- Hazardous Products Act: requires suppliers of hazardous products to communicate those hazards through product labels and safety data sheets as a condition of sale and importation.

- Privacy Act: protects the privacy of individuals with respect to personal information held by government institutions and covers the collection, use, disclosure, retention and disposal of that information in the administration of programs.

- Immigration and Refugee Protection Act has provisions related to the protection of public health (s. 38) and longstanding program structures for implementing these provisions, through health admissibility screening in the immigration system.

Policies and other government instruments

Because of the differences in legislation between the federal and provincial and territorial levels, Canada has mechanisms, agreements and plans in place (for example, the Health Portfolio Emergency Response Plan, the Canadian Pandemic Influenza Preparedness Planning Guidance for the Health Sector, and the Strategic Emergency Management Plan) that enable national coordination, particularly during public health emergencies that require federal involvement.

The Pan-Canadian Public Health Network is a national body that strengthens and enhances Canada's public health capacity and enables federal, provincial and territorial governments to work together on the day-to-day business of public health and to anticipate, prepare for and respond to public health events and threats.

The Network includes the Public Health Network Council, the Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health and three steering committees: Healthy Peoples and Communities; Public Health Infrastructure; and Communicable and Infectious Diseases. The Network was designed to support public health within a federated system where each level of government has its own area of responsibility. The Network's guiding principles are:

- Respect for the authority of each government to manage operations within their own domain

- Embrace differences in how governments exercise their public health responsibilities, set priorities and manage infrastructure

- Recognize that there is no "one size fits all" approach to public health

- Collaborate with non-governmental organizations

The Network's newly developed Blueprint for a Federated System for Public Health Surveillance in Canada (Blueprint), is a framework and action plan to formalize key elements of public health surveillance in Canada, such as governance, standards, ethics, information sharing, and performance measurement.

Canada's Multi-Lateral Information Sharing Agreement came into force in 2014. It is a legal agreement that establishes standards and deals with the sharing, use, disclosure and protection of public health information for infectious disease surveillance and public health emergency response. Until all technical annexes to the Agreement are completed, parts of an earlier federal, provincial and territorial Memorandum of Understanding on the Sharing of Information during a Public Health Emergency are still in effect.

In addition, the IHR National Focal Point for Canada-a funded program within the Agency-has joined with other federal departments and agencies to put in place policy and administrative arrangements to implement the IHR. Among these is a memorandum of understanding between the Agency and the Department of National Defence allowing the Department of National Defence to inspect and issue ship sanitation control certificates and ship sanitation control exemption certificates for Canadian Armed Forces vessels.

The IHR National Focal Point did a Privacy Impact Assessment in 2016 to ensure its compliance with Canada's Privacy Act in its collection, retention and distribution of information as part of the requirements under the IHR. The Assessment did not identify any high-level risks.

The IHR National Focal Point is also coordinating the development of guidance on how international case and contact notices (that might be shared with other States Parties National Focal Points) are managed from receipt to retention and distribution, ensuring compliance with relevant Canadian laws and policies.

The Federal Nuclear Emergency Plan describes the Government of Canada's preparation and response arrangements for managing the radiological health consequences of a nuclear emergency. The Plan has provincial annexes for jurisdictions having nuclear power plants or ports visited by nuclear powered vessels. These annexes establish the link between federal and provincial nuclear emergency response organizations and capabilities.

Canada is a signatory to the Convention on Early Notification of a Nuclear Accident and has arrangements in place for timely notification of a nuclear accident to the International Atomic Energy Agency, and for coordinating with the IHR National Focal Point to report to the World Health Organization (WHO). (See also section RE: Radiation emergencies.)

Examples of cross-border agreements supporting health security

Canada is an active partner in several formal and informal cross-border agreements and networks that support the IHR, health security, and collaboration at the global, regional and sub-regional levels. These include the Global Health Security Initiative, the Global Health Security Agenda, and the North American Plan for Animal and Pandemic Influenza (NAPAPI).

NAPAPI supports IHR implementation. It is a framework for comprehensive health security across all relevant sectors in the North American region. Its function is to protect against, control, and provide a public health response to animal and pandemic influenza in North America while avoiding unnecessary interference with international travel and trade.

NAPAPI complements national emergency management plans in the United States, Canada and Mexico. It builds on the principles of the International Partnership on Avian and Pandemic Influenza and on the standards and guidelines of the World Organization for Animal Health, WHO, the World Trade Organization, and the North American Free Trade Agreement.

To further enhance regional cooperation for health security, the three countries also have a long-standing informal practice of supporting cross-border "collaboration and assistance" (IHR, article 44) by sharing notifications to WHO of potential Public Health Emergencies of International Concern (IHR, article 6) and routine technical reports for the purposes of public health follow-up.

P1.2 The State can demonstrate that it has adjusted and aligned its domestic legislation, policies and administrative arrangements to enable compliance with IHR

Evidence that IHR implementation has been effective in Canada

An internal capacity assessment in 2010-validated by legal counsel in 2015-found that Canadian legislation and regulations were sufficient for IHR compliance and therefore no changes were recommended for IHR implementation. However, Canada understands that the public health landscape is constantly evolving. Through routine performance evaluation processes, and occasional independent investigations, governments in Canada identify and address gaps and weaknesses in existing government instruments.

The Quarantine Act, updated in 2005, serves as a good example of this. Since its implementation, several public health events have underscored challenges regarding the act and increased expectations for federal preparedness and response. Through the Border and Travel Health Modernization Initiative - an opportunity to refresh Canada's approach, strengthen collaboration, and better support compliance with the IHR-Canada is reviewing its legislation and policy, as well as other instruments, and adapting its approach to reflect a changing reality.

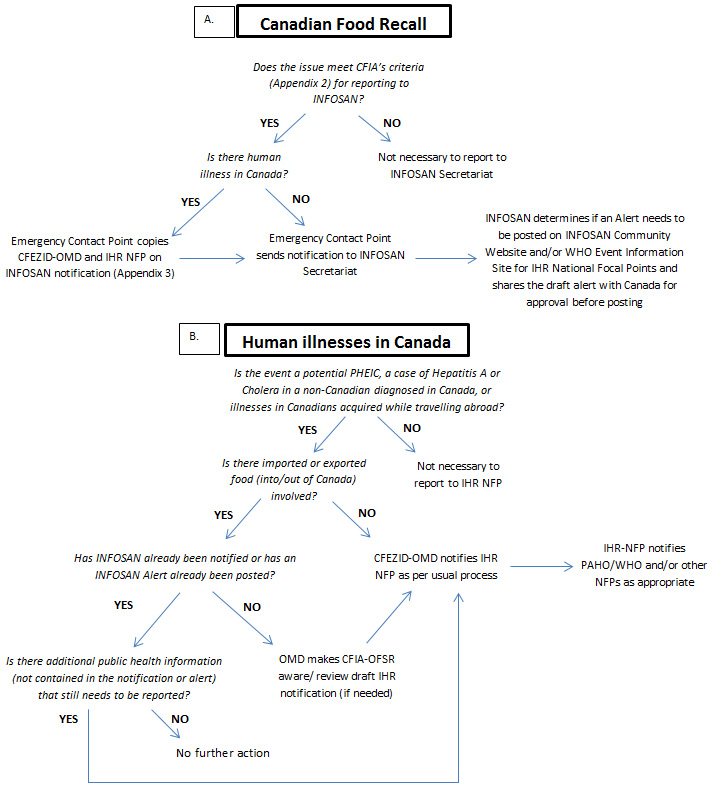

Certain policy and administrative arrangements have also been made to improve compliance with the IHR. Following a large Salmonella outbreak in 2014, the Public Health Agency of Canada, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency and Health Canada developed a joint protocol for IHR communications related to food safety issues. The protocol describes how Health Portfolio partners share information with the International Food Safety Authorities Network and WHO during an event with international implications. The protocol also outlines roles and responsibilities and describes reporting mechanisms and requirements to address duplication of effort and to better align messages.

Similarly, protocols have been put in place with the IHR National Focal Point to align reporting requirements in the event that Health Canada's Radiation Protection Bureau reports a real or potential nuclear emergency to the International Atomic Energy Agency under the Convention on Early Notification of a Nuclear Accident.

Best practices, challenges, gaps and recommendations

The Public Health Agency of Canada was created in 2004-with input from provinces, territories, stakeholders, and Canadians-in response to growing concerns about the capacity of Canada's public health system to anticipate and respond to public health threats. The Agency and the Chief Public Health Officer of Canada provide a focal point for federal leadership in managing public health emergencies.

Several provinces (including British Colombia, Ontario, and Quebec) have created their own leadership mechanisms for public health events and emergencies. These centres of expertise for managing public health risks and threats have improved Canada's capacity and leadership in both domestic and international health security. This multi-level arrangement can be viewed as a best practice in a federated state, such as Canada, that relies on strong multi-sectoral engagement and collaboration.

The Agency uses a results-based management approach to support its public health interventions.

As part of this approach, the Agency incorporates specific indicators from the Joint External Evaluation tool and the IHR annual monitoring tool into its regular planning and reporting process. This approach promotes accountability and comparability for delivering essential public health functions. Further, it supports priority-setting and resource allocation, and reinforces the concept that IHR implementation is fully integrated into public health planning and reporting in Canada. The Agency and all other federal departments must report annually to the Canadian public on plans and priorities, expected results, expenditure plans, and performance measurement.

In Canada, implementation of the IHR is enabled through broad health and emergency management legislation. This is supplemented by policy and administrative instruments and accompanied by public health or health-related provincial and territorial legislation. No major legislative gaps have been identified that might prevent the full implementation of the IHR. Canada nonetheless recognizes that policy and administrative instruments may need to be developed or revised to:

- Enable better coordination between legal frameworks

- Strengthen or clarify roles and responsibilities

- Improve performance of activities supporting IHR implementation

- Help address action items resulting from this Joint External Evaluation

P2: International Health Regulations coordination, communication and advocacy

Joint external evaluation target: The effective implementation of the International Health Regulations 2005 (IHR) requires multi-sectoral/ multidisciplinary approaches through national partnerships for effective alert and response systems. Coordination of nationwide resources, including the sustainable functioning of a National IHR Focal Point, which is a national center for IHR communications, is a key requisite for IHR implementation. The National Focal Point should be accessible at all times to communicate with the World Health Organization (WHO) IHR Regional Contact Points and with all relevant sectors and other stakeholders in the country. States Parties should provide WHO with contact details of National Focal Points, continuously update and annually confirm them.

Level of capability in Canada

In July 2005, the Public Health Agency of Canada was designated as the IHR National Focal Point for Canada. It is comprised of an IHR Program team and an IHR Operations function and is supported by the Health Portfolio Operations Centre Watch Office (Watch Office). The Agency performs the four mandatory functions of the National Focal Point as required under the IHR and several additional activities outlined in the WHO National Focal Point Guide.

Canada regularly validates the capacity of its National Focal Point. This is done through informal internal monitoring and assessment, twice yearly communication tests conducted by the WHO Regional Contact Point, and the WHO annual self-assessment.

The success of IHR implementation in Canada relies on ongoing collaboration among relevant sectors on issues of shared responsibility. Several collaborative groups meet regularly to ensure Canada fulfills its IHR responsibilities. One example is the IHR Implementation Working Group, made up of technical and policy experts from the Health Portfolio and other relevant federal departments.

There is also a network of IHR Champions in relevant federal, provincial and territorial government departments. These ensure that the IHR are reflected in regular operational activities and policy development processes. When required, existing federal/provincial/territorial governance mechanisms, task groups and emergency response plans are leveraged to support IHR implementation.

Indicators

P.2.1 A functional mechanism is established for the coordination and integration of relevant sectors in the implementation of IHR

Structure of Canada's IHR National Focal Point

Canada's IHR National Focal Point coordinates the implementation of the IHR on behalf of the Government of Canada. IHR implementation is shared by federal, provincial and territorial governments. The IHR National Focal Point is an implementation hub, providing advice, policy recommendations, advocacy and training, and stakeholder outreach. It also coordinates IHR monitoring and evaluation activities, including annual reporting to the World Health Assembly on behalf of the Government of Canada.

The Watch Office assumes the operational function of the IHR National Focal Point through around-the-clock service as a communications hub. Specifically, the Watch Office coordinates urgent communications concerning the implementation of IHR articles 6 to 12. The team provides critical situational awareness by gathering, organizing and redistributing stakeholder information on public health threats and risks. They also maintain internal tools for IHR communication, such as protocols, distribution lists, and templates.

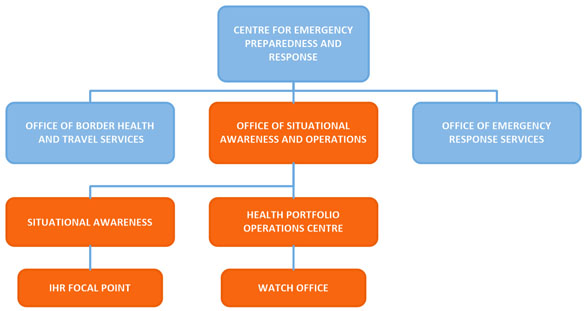

Figure 1: IHR National Focal Point organizational structure - Text description

Figure 1 figure depicts the organizational structure of Canada's IHR National Focal Point. At the top of the organizational chart is the Centre for Emergency Preparedness and Response. The Centre is comprised of three offices: the Office of Border Health and Travel Services, the Office of Emergency Response Services, and lastly the Office of Situational Awareness and Operations. Within the Office of Situational Awareness and Operations there are two key sections to note: Situational Awareness and the Health Portfolio Operations Centre. The IHR National Focal Point falls under the Situational Awareness section and The Watch Office falls under the Health Portfolio Operations Centre. The Office of Situational Awareness and Operations and the areas that stem from it are all coloured in orange to indicate that these areas work together to deliver IHR NFP functions and services. All other teams are displayed in the colour blue.

The Watch Office program achieves 24-hour coverage using two teams: day-time watch officers and after-hours duty officers. During an event or emergency, a dedicated event watch officer is assigned to monitor and triage all event-related operational communications. An IHR technical advisor, generally a public health or health professional, is also available to assist the National Focal Point with assessing and reporting events (using the Annex 2 decision instrument), and with other activities. Advisors are accessible both during and outside regular business hours. The NFP also regularly consult program staff with specific disease expertise. The Vice President of the Health Security Infrastructure Branch (Public Health Agency of Canada) provides oversight on IHR implementation as the IHR Responsible Person in Canada.

IHR National Focal Point staff work closely with stakeholders to align program, policy, operational, legal, and privacy considerations to ensure that Canada continues to meet its assessment and reporting obligations under the IHR.

IHR Champions are designated points of contact in relevant federal, provincial and territorial government departments. They are familiar with Canada's obligations under the IHR and promote and support IHR implementation within their jurisdictions. IHR Champions act as a conduit and contact point for regular information exchange between the IHR National Focal Point and other government stakeholders in Canada.

Collaboration among multiple sectors is facilitated by a working group composed of technical and policy experts from the Health Portfolio and other relevant federal departments. The group meets regularly to support initiatives related to the implementation of the IHR in Canada. It has contributed to a variety of implementation activities, including Canada's Joint External Evaluation, annual self-assessment reports to the World Health Assembly, and other international capacity building activities. The working group does not facilitate collaboration during health emergencies.

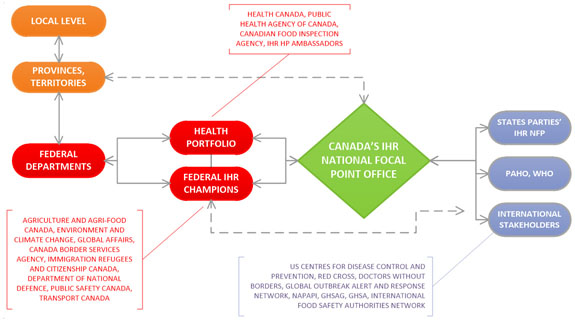

Figure 2: Coordination and information flow between Canada's National Focal Points and other sectors - Text description

Figure 2 diagram illustrates the flow of information and the coordination between Canada's National Focal Point and other sectors. In the top left corner in orange are two ovals representing jurisdictions across Canada. The first oval is the Local level and there is a two-headed arrow connecting it to the oval for Provinces/Territories below it, indicating a 2 way flow of information. The Provinces/Territories oval has a 2-headed dotted arrow connecting it to Canada's IHR National Focal Point Office in the centre of the diagram in a green diamond, and another 2-headed arrow connecting it to Federal Departments below it in a red oval, emphasizing the multi jurisdictional and multi-sectoral coordination that occurs.

To the right of the Federal Departments oval are two additional red ovals. The top one represents the Health Portfolio and the bottom one is Federal IHR Champions. The Health Portfolio is comprised of Health Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada, Canadian Food Inspection Agency and Health Portfolio IHR Ambassadors. Federal IHR Champions include representatives from: Agriculture and Agri-food Canada; Environment and Climate Change Canada; Global Affairs Canada; Canada Border Services Agency; Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada; Department of National Defence; Public Safety Canada; and Transport Canada. There are 2-way arrows connecting the 3 Federal ovals, as well as an arrow leading from these federal entities to the IHR National Focal Point Office.

On the right side of the diagram are 3 blue ovals representing States Parties IHR NFP; PAHO / WHO; and International Stakeholders. International Stakeholders include US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, Red Cross, Doctors Without Borders, Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network, NAPAPI, GHSAG, GHSA, International Food Safety Authorities Network. There are double sided arrows depicting information flow to/from these international bodies to Canada's IHR National Focal Point Office. There is also a double-sided dotted arrow leading back from these international groups to the Federal IHR Champions.

The Public Health Agency of Canada uses existing governance mechanisms to update partners in other relevant sectors on Canada's IHR-related activities. These mechanisms include the Pan-Canadian Public Health Network, the Council of Chief Medical Officers, the Public Health Infrastructure Steering Committee and the Communicable and Infectious Disease Steering Committee.

In addition to these day-to-day coordination mechanisms, Canada maintains several national emergency response plans (see section R1: Preparedness) and mutual aid agreements to improve response capacity (see sections R2: Emergency response operations and R4: Medical Countermeasures and personnel deployment).

Standard operating procedures, guidance documents and tools

As a best practice, Canada's IHR National Focal Point has developed a comprehensive standard operating procedure with two stand-alone components. One is a high-level strategic overview of Canada's IHR National Focal Point. It outlines its mandate and functions, stakeholder roles and responsibilities, and communication and coordination processes.

The other component is a detailed technical Guidebook for IHR Assessment and Reporting at the Federal (national) Level. This Guidebook supports the Health Portfolio program areas and technical experts in fulfilling their IHR duties to identify, assess, and notify WHO of certain public health events and other reporting requirements. It also includes useful information for all domestic stakeholders with IHR assessment and reporting responsibilities.

The National Focal Point also develops protocols, procedures, process flow maps, and templates to facilitate IHR communications and coordination. This includes the development of a guideline for sharing International Health Regulations notifications of events in Canada with the Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health and IHR Champions.

Individual Health Portfolio programs and other government departments are responsible for developing their own internal processes and procedures for detection, assessment, and reporting public health events, and for communicating relevant events to the IHR National Focal Point.

The IHR National Focal Point has developed additional communication tools to build an IHR community of practice in Canada. These include:

- Online educational resources for basic IHR understanding

- Training courses that provide in-depth operational knowledge and practice for IHR experts within the Health Portfolio

- Presentations to increase awareness of the IHR requirements and strengthen collaboration between sectors

Evaluation and testing of National Focal Point functions

Canada has confirmed its capacity to deliver the four mandatory core functions of a National Focal Point outlined in the IHR and WHO's guidance for National Focal Points in annual self-assessment reports to the World Health Assembly. In the 29th Pan American Sanitary Conference information document on IHR implementation, Canada is recognized as one of 12 States Parties in the Americas that have consistently submitted a State Party Annual Report since the requirement was instituted in 2011.

Canada's IHR National Focal Point performance is regularly monitored and assessed on an informal basis. For example, employees continually monitor the quality and timeliness of IHR communications. The team meets regularly to discuss operational issues, to review and revise internal IHR-specific processes, and to discuss ways to improve services.

Protocols are updated annually and as required. In addition, the National Focal Point staff host an on-going cycle of training and refresher sessions to raise awareness of IHR obligations and to ensure program standards are met. It also conducts regular outreach and provides training to other stakeholder groups (see D3: Reporting).

IHR coordination and communications are also reviewed following a response to an event or emergency. The results of these reviews inform the adjustment of internal protocols, procedures and practices to ensure they are suited to operational realities and emerging challenges.

To ensure the effectiveness of IHR communication functions, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO), as the WHO IHR Regional Contact Point, conducts twice yearly tests with the designated IHR National Focal Point of States Parties in the Region. Canada's IHR National Focal Point has scored highly on all recent tests. No gaps or incidents of miscommunication have been identified. Nonetheless, these communication tests provide a valuable opportunity for the National Focal Point to review its internal processes and procedures, and to address any issues or deficiencies.

The Public Health Agency of Canada evaluated its emergency preparedness and response program to assess the program's core activities, including relevant IHR National Focal Point activities.

Best practices, challenges, gaps and recommendations

Over the past few years, Canada's IHR National Focal Point has focused efforts on building a foundation for its structure and processes within the Health Portfolio. As a result, Canada has a well-established and fully functional National Focal Point with the capacity to connect with WHO and partners for urgent IHR-related communications.

As a best practice, dedicated staff have been trained and made available to deliver on the National Focal Point's mandatory functions. Guidance documents and tools have also been developed to support these functions. One of the National Focal Point's key strengths is its streamlined approach to coordinating IHR-related communications and information flows.

IHR implementation is a shared responsibility in Canada. Consequently, the National Focal Point plans to strengthen partnerships between sectors by formalizing and standardizing collaboration and communication with federal, provincial and territorial stakeholders, including IHR Champions.

To do this, the National Focal Point will draw on the accumulated experience of the many sectors involved to improve IHR monitoring and evaluation activities, which include the annual reporting process. It will also keep stakeholders updated on implementation progress and establish clear links between health emergency management functions and IHR Champions in order to leverage parallel knowledge and expertise.

Ongoing outreach and training across government on IHR obligations and processes will therefore be key to ensuring that Canada continues to meet its requirements for IHR coordination, communications and advocacy. By building a strong domestic network or community of practice, the National Focal Point is laying the groundwork for open dialogue and information exchange among federal, provincial and territorial partners.

Canada's National Focal Point will also continue to work with PAHO/WHO, the United States, Mexico, and other partners on joint National Focal Point strengthening initiatives. Examples include peer-to-peer exchanges, training opportunities, and the development of valuable resources to help strengthen core capacities related to National Focal Point functions.

These opportunities foster a global community of practice and encourage open communications among National Focal Points. The result is more efficient and effective IHR-related communications within the Americas and beyond. This collaboration helps bolster overall health security and allows Canada to apply lessons learned from other countries to strengthening its National Focal Point capacities.

P3: Antimicrobial resistance

Joint external evaluation target: Support work being coordinated by the World Health Organization, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, and the World Organization for Animal Health to develop an integrated global package of activities to combat antimicrobial resistance. The package spans human, animal, agricultural, food and environmental aspects (i.e. a One Health approach). These activities include:

- Each country having its own national comprehensive plan to combat antimicrobial resistance;

- Strengthening surveillance and laboratory capacity at the national and international level following agreed international standards developed in the framework of the Global Action plan while considering existing standards;

- Improving conservation of existing treatments and collaboration to support the sustainable development of new antibiotics, alternative treatments, preventive measures and rapid, point-of-care diagnostics, including systems to preserve new antibiotics.

Level of capability in Canada

In September 2017, the Government of Canada released a new framework, Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance and Antimicrobial Use: A Pan-Canadian Framework for Action. The Framework strengthens Canada's ability to combat the risks of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in a coordinated and effective way

to minimize the impact of AMR, and to ensure that antimicrobials will continue to be an effective tool in protecting the health of Canadians. The Framework is grounded in a One Health approach, and developed with experts from the health, public health, veterinary and agriculture and agri-food sectors. Its four components are surveillance; infection prevention and control; stewardship; and research and innovation.

Addressing the threat of AMR in Canada requires the involvement of federal, provincial and territorial governments, health professionals, academia, industry, professional organizations (human and animal stakeholders) and the public. These groups must collaborate, coordinate and leverage activities across sectors to minimize duplication and to create effective, sustainable solutions.

AMR governance to guide the development of the Pan-Canadian Framework and Action Plan has three tiers: a Deputy Minister Champion Committee, an AMR Steering Committee, and four task groups (one for each of the Framework components). This structure has links to national health sector decision-making groups, such as the Public Health Network Council, the Council of Chief Medical Officers of Health, and the Conference of Deputy Ministers of Health. It also links to national agriculture sector committees through the Council of Chief Veterinary Officers, assistant deputy minister level regulatory and policy committees, and the federal, provincial and territorial ministers of agriculture. A federal interdepartmental committee (with representation from 11 departments and agencies) provides overall strategic direction and leadership for the Canadian response to AMR and for Canada's contribution to the international AMR agenda.

Canada has many surveillance systems in place to detect many of the AMR pathogens prioritized by the WHO. These systems include the Public Health Agency of Canada's nine national surveillance programs that track antimicrobial use (AMU) and AMR in both humans and animals. The data collected from these programs informs research and policy.

The Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System produces an annual report using information from national surveillance programs. Canada also has designated laboratories that can detect and report on AMR. One of these is the National Microbiology Laboratory, which is a Level 4 reference laboratory.

Each province and territory has accredited public health laboratories that can conduct AMR detection testing and submit isolates to the National Microbiology Laboratory for serotyping or susceptibility testing, and whole genome sequencing.

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) is the national coordinator for monitoring the incidence of AMR in bacterial isolates from human infections and in enteric bacteria along the food chain. The Canadian Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Program is responsible for clinical surveillance. The Program encompasses 65 acute-care hospitals which serve as sentinel surveillance sites for many healthcare associated infections, including infections due to Clostridium difficile and antibiotic-resistant organisms such as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Canada also collects some data on antibiotic-resistant organisms in community settings, including long-term care facilities.

For surveillance along the food chain, the Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance collects AMU data (national sales data, and farm-level data), and gathers cecal and other samples for AMR testing from farms, abattoirs, and retail food isolates. It also does AMR testing on clinical Salmonella isolates from animals and humans. Surveillance data from these systems is aggregated and publicly reported.

The delivery of health care in Canada is largely the responsibility of the provinces and territories. The federal government publishes evidence-based national guidance on infection prevention and control to inform and complement provincial and territorial guidelines, standards and protocols. This guidance is also used by different jurisdictions and facilities in the development of their policies and protocols.

In 2016 PHAC published Routine Practices and Additional Precautions for Preventing the Transmission of Infection in Healthcare Settings. PHAC is currently updating the 2002 version of the national guidelines on the prevention and control of occupational infections in health care. In addition to infection prevention and control policies, standards and plans for their health care facilities, most provinces and territories have access to designated infection control professionals on-site or through teaching hospitals.

The availability of isolation units in Canadian hospitals is high, although their capacity varies. Canada also has ad hoc measures in place to assess the effectiveness of infection prevention and control measures and share results.

As with health care, animal health care is largely the responsibility of the provinces and territories. Health Canada approves antimicrobials for sale for use in animals, whereas the provinces and territories control the distribution of antimicrobials and regulate the practice of veterinary medicine, At the farm level, National Biosecurity Standards and Biosecurity Principles, developed by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA), in collaboration with producer organizations, provincial and territorial governments and academia, complement voluntary on-farm food safety programs.

The 2015 Federal Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance and Use in Canada: Building on the Federal Framework for Action includes commitments to strengthen the promotion of the appropriate

use of antimicrobials in human and veterinary medicine, and to continue to strengthen the regulatory framework for veterinary medicines and medicated feeds. Health care facilities across Canada have implemented antimicrobial stewardship programs and identified best practices. Veterinary Oversight of Antimicrobial Use – A Pan-Canadian Framework for Professional Standards for Veterinarians, guidelines and standards are in place to support the prudent use of antimicrobials in animals.

Health Canada monitors antibiotic sales and the number of prescriptions for human drugs using data collected from community pharmacies and hospitals, which it purchases from IMS Health Canada Inc. PHAC analyzes this antibiotic use data. Pilot studies are underway to improve our understanding of prescription practices for certain classes of antibiotics and select indications.

Health Canada regulates and approves veterinary drugs. Policies and regulations outlined by Health Canada related to feed are implemented and regulated by CFIA. PHAC analyses data provided by the Canadian Animal Health Institute on the annual volume of veterinary antibiotics distributed for sale in Canada. Additionally, Canada collects data on antimicrobial use at the farm level through the Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance sentinel farm program.

Health Canada maintains a Prescription Drug List, which is a list of medicinal ingredients that, when found in a drug, require a prescription for use in humans and animals. All systemic antibiotics in humans require a prescription in Canada, and all medically-important antibiotics for use in animals will require a prescription as of December 1, 2018.

Indicators

P.3.1 Antimicrobial resistance detection

National AMR plans

In September 2017, the Government of Canada released Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance and Antimicrobial Use: A Pan-Canadian Framework for Action. The Pan-Canadian Framework provides an overarching policy frame that lays out strategic goals and guiding principles to address antimicrobial resistance (AMR) in Canada. Specifically, it outlines the need for action across all jurisdictions and implicated sectors in the areas of: surveillance; stewardship; research and innovation; and infection prevention and control.

The Pan-Canadian Framework builds on previous plans that were developed to address AMR. In October 2014, the Government of Canada released Federal Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance and Use in Canada: Building on the Federal Framework for Action, which maps out a coordinated, collaborative federal approach to responding to the threat of AMR. In March 2015, the Federal Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance and Use in Canada: Building on the Federal Framework for Action was published. It identifies concrete steps to be taken by key federal departments and agencies to achieve the goals of the federal framework, including efforts to establish and strengthen surveillance systems.

Surveillance programs for AMR bacteria in Canada

Surveillance is a shared jurisdictional responsibility in Canada. There are data sharing agreements in place between federal, provincial and territorial partners. Surveillance is also one of the four pillars of the Pan-Canadian Framework. There are multiple surveillance systems in place at different levels of government in Canada that collect data on anti-microbial resistance and anti-microbial use (AMU) in human and animal settings, such as hospitals, community settings, agricultural settings and farms. The data from these systems is used to inform and update AMU and infection control policies.

- The Canadian Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance System provides an integrated picture of AMR and AMU in Canada based on surveillance data from laboratory reference services and PHAC's surveillance systems that track identified priority organisms and AMU in humans and animals.

- The Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Resistance Surveillance monitors trends in AMU and AMR in selected bacterial organisms from human, animal and food sources across Canada. The program is based on several representative and methodologically unified surveillance components. These are linked to examine the relationship between antimicrobials used in food-animals and humans and the associated human health impacts. This information supports the creation of policies to control AMU in hospital, community and agricultural settings and the identification of appropriate measures to contain the emergence and spread of resistant bacteria between animals, food and people in Canada.

- In Canada, the list of nationally notifiable diseases for humans covers infectious diseases that have been identified by the federal government and all provinces and territories as priorities for monitoring and control efforts-this includes resistant microbes. Through the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System, provinces and territories voluntarily submit annual notifiable disease data which are used to produce national disease counts and rates.